Buravleva stock / Shutterstock.com

You get to work, look at an overflowing inbox, attend meetings all day, work on urgent contracts (seemingly all at the same time) and you get it all done! Next day, you see the same inbox, have similar meetings and have a meltdown! Sound familiar? Stress was involved both days – but on the first day you took control of your stress and made it work for you.

In the final article in our series on how to sustain long-term careers, I talk to GCs Freya Smith, Catriona McGregor, Teresa Cleary, Kate Jones, and Chad Aboud about their relationships with stress. I also spoke with Professor Selena Bartlett, a neuroscientist and author of Smashing Mindset and host of Thriving Minds podcast who says, “We can become the boss of [stress] by physically training the way you would a muscle.”

First, she recommends becoming aware of how stress has wired your brain. How are you coping with it? How do you know if you are stressed out? Professor Bartlett asks people to look at what they are eating and drinking and at what time. When you are reaching for chocolate, or one glass of wine becomes two, are signals that you may be stressed. It is the brain’s way of handling stress. We are not handling stress in healthy ways.

After identifying how we currently cope with stress, we can consider how to train our brains to manage stress and make it work for us.

What do GCs think of when they hear the word “stress”?

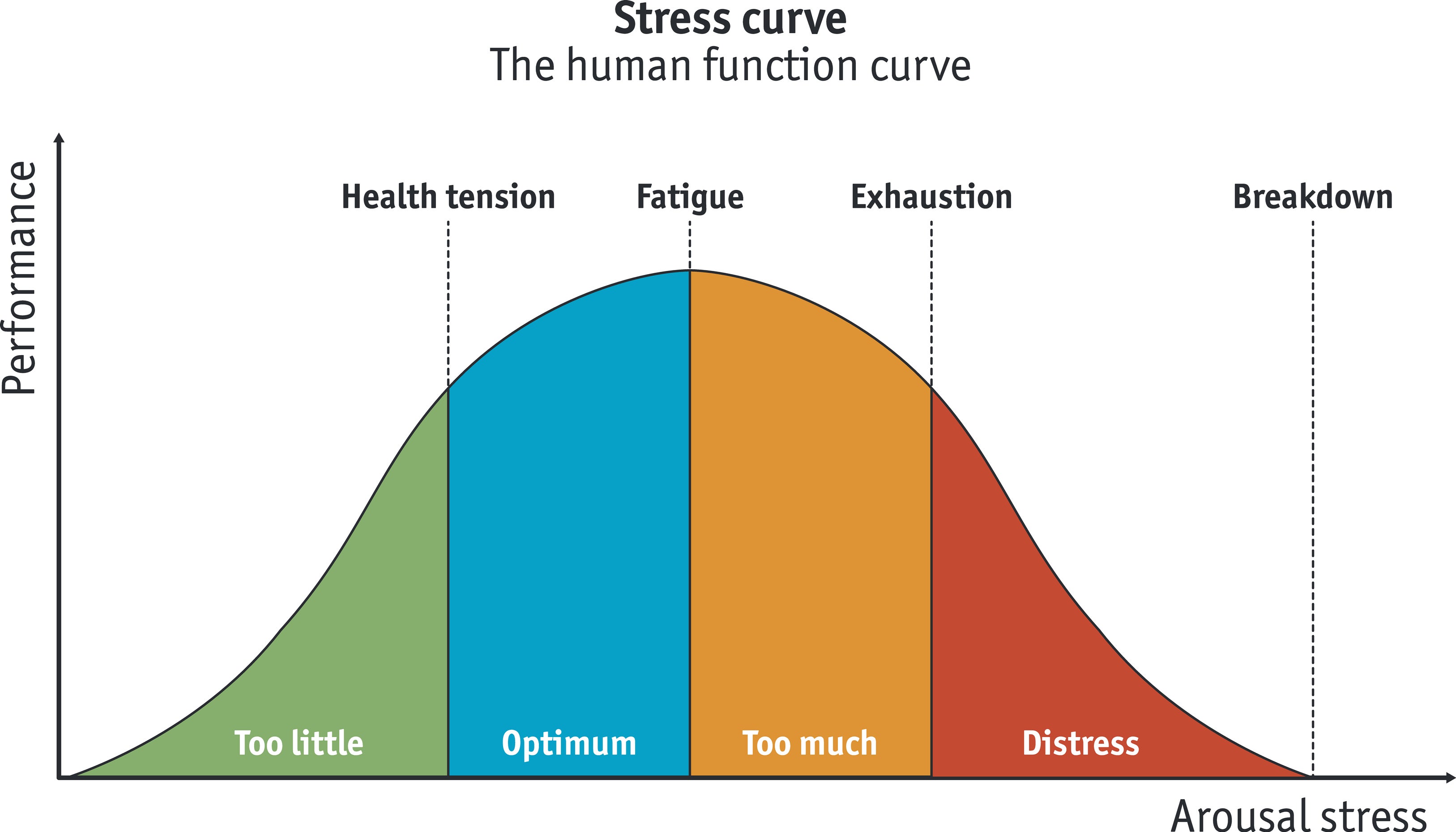

Smith thinks of Nixon P’s 1979 stress curve showing the relationship between stress and performance and how both increase to a certain point. While low levels of stress leave people feeling bored or unchallenged, if stress becomes overwhelming, performance levels start to decline and it can lead to burnout.

“I think for most lawyers, who are highly driven and ambitious, pressures and demands can facilitate higher levels of performance. It’s when stress is, or is perceived as, uncontrollable or unmanageable that there is a decrease in performance,” Smith says.

While low levels of stress leave people feeling bored or unchallenged, if stress becomes overwhelming, performance levels start to decline and it can lead to burnout.

-Freya Smith, General Counsel and Secretary, Claim Central Consolidated

The stress relationship will be different for each person and may be impacted by life events. For example, a lawyer who is given a short but adequate deadline, will be motivated to work actively and efficiently. However, the same tight deadline given to a lawyer at a time they are responsible for childcare coupled with a sick relative may create an overwhelming mix of situations. If not managed carefully, it may result to a poor performance, ill health, and burnout. The key is understanding when you and members of your team might be approaching the “fatigue point.”

McGregor sees stress as a positive, up to a limit. “Stress can give me adrenaline and I generally perform better, deliver more output, and think more quickly with a little bit of pressure and stress. However, too much stress clearly can have a negative impact.”

While short bursts of stress are “usually manageable and have a positive impact,” prolonged stress can have a negative impact. “My way of dealing with stress in a deal scenario,” she says, “where the deal may go on for several months, is it to break it down into phases and take small breaks or celebrate small wins after each phase so the stress can be diffused before perhaps building again.”

An advocate of exercise, McGregor includes this in her routine during moments of high stress: “I find running a great way to clear my head, refocus my mind, work through actions, or plan out conversations I need to have.” She also finds music is a great stress reliever. “I love playing some cheesy pop or old Ibiza classics dance tunes to lift my spirits at a time of stress,” she shares.

Cleary thinks “a healthy amount of stress is good as it motivates you and enables you to focus your energy but too much stress, as we know, can just overwhelm and paralyze you.” She agrees that in-house lawyers like that healthy amount of stress to perform well.

However, she says, “the role of the in-house lawyer has evolved and is often a highly stressful role. This is particularly so now that we are faced with reduced resourcing and sophisticated and demanding internal clients, and colleagues.”

Her tips to reduce stress include “designating your own health and well-being above all as you will not otherwise be able to manage those times of intense stress.” Ordering your work by priority (or removing some work altogether) can alleviate stress.

She recommends learning to communicate with your commercial stakeholders on your workload and their priorities which becomes easier with experience. “This takes away some of the stress and enables you to perform. I am a big believer in communicating and not just letting work overwhelm me,” Clearly advises.

Aboud says that, while pressure keeps him motivated, he knows that it is “the volume and constant nature of the stress” that burns people out.

He is conscious of the fact that each person responds differently to stress and has a different threshold for stress and thinks we should regulate “how often we exist in that high driven environment.”

His tip for managing stress: “Reflect on who we are and use that to assess how much stress we want and need in our work and lives.”

Jones says the law “attracts high performing individuals who often have a perfectionist streak. Perfectionism and stress don’t go well together as we all find in our personal lives and work lives that nothing ever goes to plan.”

She thinks in-house lawyers often find themselves in “stressful situations where that basic flight or fight response is triggered.” She thinks junior lawyers often haven't developed strategies to cope with stress often blaming themselves when something goes wrong or not according to plan. More senior lawyers understand things go wrong all the time, for a range of reasons, which often have nothing to do with anything they did or didn’t do. “Self-awareness,” Jones says, “is so important. Being aware of how your body is responding to the stressful situation is critical to then put practices in place to manage that stress.”

Perspective is equally important and is developed through experience and understanding that “hurdles along the way are challenging but surmountable.” She thinks leaders need to “be self-aware of the impact of what you say or do” to ensure they aren't creating stress in their teams.

Leaders should, instead, focus on the positive impact they can make by sharing their experiences with their teams. “Leaders can play a positive role in helping in-house lawyers manage stress providing guidance and strategies to help lawyers learn to manage their own stress responses,” Jones shares. She adds: “I would have loved a more senior lawyer to have sat me down when I was starting out and given me some tips on how they managed stress. But in the late 90s, when I started out, no one talked about stress; it was like it didn't exist. Hopefully, as leaders in 2022 we can have those conversations.”

Positive takeaways

Not all stress is equal

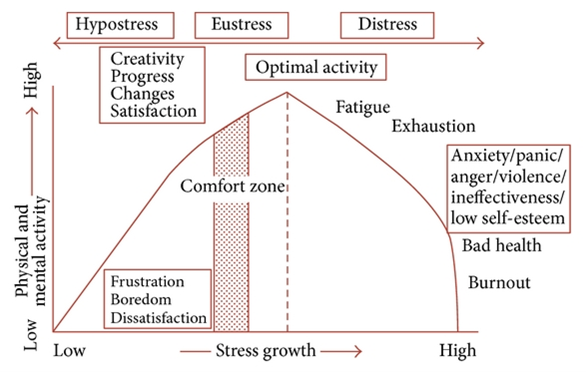

Betterup, which includes Dr. Jacinta Jiménez on its leadership team, describes stress as “the physiological response that our body, emotions, and nervous system trigger in order to prepare us for situations that demand heightened awareness.” They describe three types of stress:

- Acute stress: A short-lived stressor that goes once the danger has passed (the body’s quick reaction to save you if you step out into a busy street).

- Chronic stress: A long-lasting experience, “usually rooted in circumstances that are beyond our control,” and from which our bodies and minds don’t get the chance to recover.

- Eustress: A positive stressor that sharpens our senses “so that we can perform at our best.”

The stress response curve

Nixon P.’s stress response curve, shows the relationship between stress and performance.

Stress and performance increase together to a point of “eustress” (healthy stress) where stress is manageable within a Comfort Zone. As stress starts to feel overwhelming or too high, stress moves to “distress.” The person becomes fatigued and performance starts to decline until they experience burnout.

An example of eustress at work is working on a project which has a manageable timeline, where you can use your strengths and also learn something new. You feel stressed but can handle it. The Berkley Well-Being Institute says all stress triggers our “fight or flight response … the chemical reaction in our brain and body that results in hormones (such as adrenaline and cortisol) entering our bloodstream to give us that sudden burst of energy.” This energy helps “provide motivation and focus to confront or solve problems” – this is eustress. The flow state, which positive psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called the secret to happiness (discussed in my earlier article), has also been described as the “ultimate eustress experience.”

In contrast, unrealistic timelines, or too many simultaneous commitments, will move us towards distress – feeling overwhelmed or anxious.

How can we make stress work for us?

Everyone manages stress differently and benefits from different protocols. Try some of the suggestions below to see if any of them work for you when you want to use stress to help relieve your mood or get into some challenging work you want to concentrate on.

Change your stress mindset

In the Stanford Business Podcast Think Fast, Think Smart, Assistant Professor of Psychology Dr. Alia Crum discusses her work at Stanford Mind & Body Lab studying how people can benefit from stress. When asked how someone can harness a different mindset if they are nervous about an upcoming presentation or meeting, she suggests taking the following steps:

- Acknowledge you’re stressed. Accept your physiological and emotional reactions without judgement (i.e., how you respond to stress, whether it is getting hyperactive or getting sweaty palms).

- Welcome your stress. We only stress about things we care about. “I’m only stressed about x this upcoming presentation because I care about y and what is the y?” She says the “y” could be wanting to communicate something that can improve people’s lives, or “change the way we’re doing things in this company,” or not wanting to screw up the presentation and get fired “because there’s something here I feel that I really have to offer.”

- Address the reason you care. Use your stress in ways to help address the purpose [i.e., the “y”] rather than spending all your time, money, effort trying to avoid or get rid of the stress.

These three steps help people get into the mindset that stress can be enhancing. The experience of stress can help us rise to a higher level of communication, and performance, and existence.

Use stress to help focus and alertness

Betterup’s Cooks-Campbell says that, without stress “life would be pretty dull and boring,” suggesting that positive stressors give us something to look forward to, provide us with a burst of energy, help us meet challenges, helps us connect with others, sharpen our focus and attention and help us build resilience to setbacks.

Positive stressors give us something to look forward to, provide us with a burst of energy, help us meet challenges, helps us connect with others, sharpen our focus and attention and help us build resilience to setbacks.

Tips to generate positive stress

The Berkley Well-Being Institute’s suggestions to help generate positive stress:

- Learning something new every day

- Pushing yourself out of your comfort zone

- Playing games and doing puzzles

- Working out (this includes just going for walks)

- Setting goals and holding yourself accountable

- Mentoring and teaching others

- Volunteering

Positive brain training

Bartlett, the neuroscience professor, suggests changing the way the brain is handling stress by training your brain in the following healthy ways.

Have a healthy morning routine

Bartlett described her morning routine on the Common Creative podcast, “As soon as I open my eyes, I look out the window and think of three things I am grateful for before I touch my phone. There is great evidence that when you go outside and look at the wide world called panoramic vision, this suppresses your autonomic nervous system, so that gives you calmness whereas if you get straight to your phone and narrow your vision down it is more stressful to the body immediately.”

Exercise

Continue your healthy morning routine with exercise, which Bartlett does every day, saying we should all aim to move between 60 and 75 minutes daily. “Exercise,” she says on her podcast, "keeps the brain and body fit." It has been shown to "reduce stress responses and inflammation" and provides “cognitive benefits and increased learning.”

The American Psychological Association has also said that "exercise, a form of physical stress, can help the body manage general stress levels … while exercise initially spikes the stress response in the body, people experience lower levels of stress hormones like cortisol and epinephrine after bouts of physical activity.” Professor Bartlett says, “If you can’t fit in this much time, simply standing up and moving around the room is a great way to get dopamine pumping as well.”

Cold exposure

Use deliberate cold exposure to spike epinephrine and put your vision into narrow focus to concentrate on tasks. Bartlett explains: “If you have heard of Wim Hof, you know part of his method is deliberate cold exposure, this can be getting into a cold shower for 1-5 minutes which can help improve mood as well as sharpening focus, or, as you progress your tolerance, getting into an ice bath.”

During her Thriving Minds podcast episode speaking with Dr. Diwadkar (who imaged Wim Hoff’s brain), she says she went from being someone who had hot showers and never sought out the cold, to being able to build up cold tolerance starting with a cold shower. The Wim Hoff method also includes a breathing protocol to decrease stress and improve focus.

Why are healthy-stress-promoting habits important?

In addition to helping us to focus when we want to, Bartlett says that “the more you are training the brain to handle the way stress is affecting the brain’s circuits, the less likely you are to look for dopamine elsewhere, like looking for chocolate or other sugar.”

Try out some of these tips and protocols today. Find what works for you in the quest to become the boss of your brain and make stress work for you, rather than against you.

Bartlett says, “remember that you are doing a great job and because life can be short for some, these tips are guides. No matter what situation you find yourselves in, there are strategies to more than survive and thrive. Everyone deserves to be happy, healthy, and strong.”

Disclaimer: The information in any resource in this website should not be construed as legal advice or as a legal opinion on specific facts, and should not be considered representing the views of its authors, its sponsors, and/or ACC. These resources are not intended as a definitive statement on the subject addressed. Rather, they are intended to serve as a tool providing practical guidance and references for the busy in-house practitioner and other readers.