CHEAT SHEET

- Establish the “new normal.” Progressive in-house lawyers at all levels are doing more than providing legal advice. They are expected to innovate and actively seek opportunities to help the business in other ways including data governance, crisis management, government affairs, and risk.

- New skills. Traditional legal skills are no longer sufficient, and it is essential to develop “non-traditional” business skills such as process improvement, project management, design thinking, business partnership, business leadership, risk, technology, and change leadership.

- New providers. Legal conferences and free law firm updates may have sufficed in the past. Now you need to find trainers with experience in these business skills, preferably in an in-house context.

- New opportunities. Choose how you spend your training time and budget carefully. Of all the things you could learn, these “non-traditional” business skills are the ones that will allow you to add more value, collaborate, and innovate with your business colleagues, and open up more career options.

Recently, there have been many different calls to action for in-house lawyers. “You must think creatively, leverage technology, and innovate.” Another says: “You should collaborate more with your business colleagues and provide strategic business input, not just legal advice.” According to some, you need to reinvent yourself and don’t have long to do so.

Richard Susskind – “Lawyers have 5 years to reinvent ourselves” UK Law Society Conference as reported in Law Gazette April 27, 2016 UK Law Society speech. See also: Boston Consulting Group/Bucerius Law School joint report on “How Legal Technology will change the business of law” — January 2016.

You understand the importance of developing these competencies — because they are key to changing the way you work and adding more value for your organization — but the question is how? If your current approach to training and development is not geared toward helping you become more innovative, collaborative, strategic, and creative, then on what specific skills, knowledge, and experience should you focus?

The Skills for the 21st Century General Counsel Report outlined a comprehensive list of what is required to be a general counsel. Although the GC’s role is unique, many of the skills identified will also be relevant to other in-house lawyers. The report highlighted the importance of nonlegal skills and noted that “most of the skills (listed) are not new.” However, in my experience, new skills — which I refer to as “non-traditional skills” — are essential for any in-house lawyer who wants to better collaborate with their business colleagues and help both the legal department and the company innovate.

The T-shaped professional

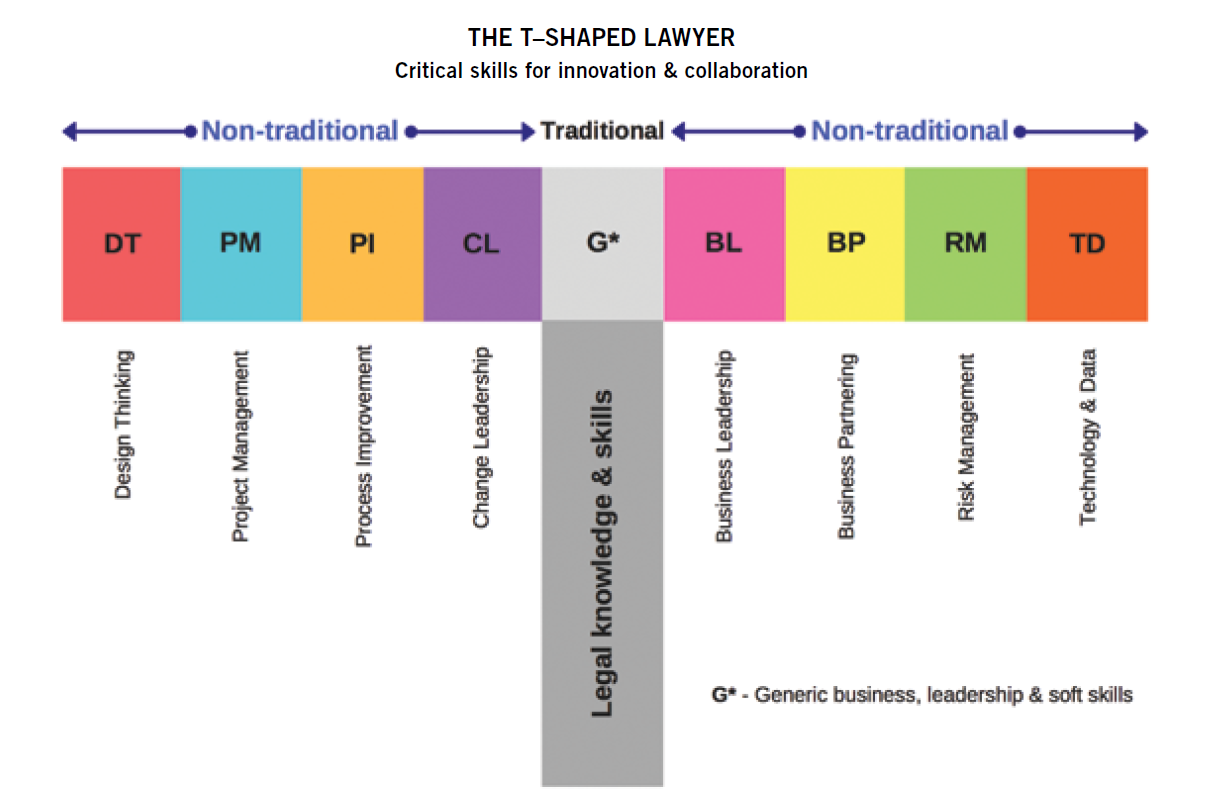

In the absence of any authoritative framework to inform which skills are critical, I looked for something to support my personal opinion about the importance of these “non-traditional” skills. I came across a helpful concept from the business world — the “T-shaped professional.”

References to T-shaped professionals and skills have been around for a while in the business world.* So, what does it mean? In simple terms, it refers to someone who has deep expertise in one discipline, fused with skills and knowledge from other areas that facilitate collaboration with specialists from different practices. According to a recent Cambridge University study, T-shaped professionals are “people who are entrepreneurial and capable of thinking in the many project roles that they may fill in their professional life. These professionals are contrasted by the more-specialized problem solvers of the 20th century, who are sometimes called ‘I-shaped’ professionals for their knowledge depth.” The study highlighted the growing imperative for service innovation through cross-functional collaboration, but found that the main obstacle is a skills or knowledge gap. To address that issue, the report recommended that companies should actively develop more T-shaped professionals throughout the organisation.

* See David Guest, “The hunt is on for the Renaissance Man of computing,” The Independent, September 17, 1991. The concept was popularized by Tim Brown, the CEO of Ideo, when referring to the type of person his famous design studio seeks to recruit.

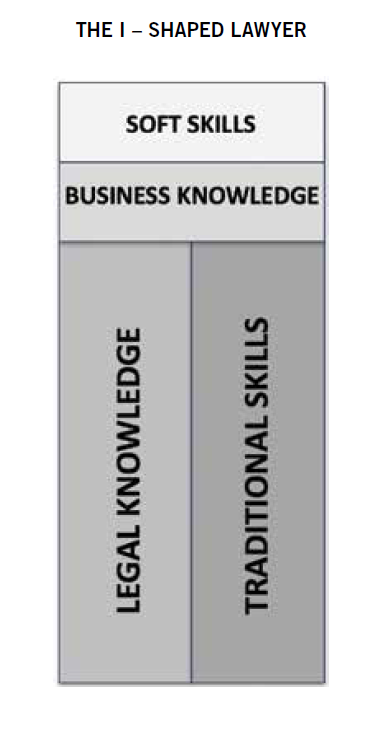

When you apply this concept to the legal world, it is apparent that most lawyers fit the profile of the I-shaped professional, as shown in the graphic above. They have a deep knowledge of certain areas of the law and their training focuses on honing that expertise. They might add some general leadership, business, or soft skills training but the primary purpose is to enhance their ability to do traditional legal work.

Is it time to consider broadening your training and development focus to become more like a T-shaped professional? If so, what might that involve? This article explores that question by first examining why in-house lawyers should develop non-legal skills. Secondly, it will consider which “non-traditional” skills, competencies, and knowledge are important and why. Finally, it will briefly outline the challenge of sourcing training for these skills.

Why should in-house lawyers develop “non-traditional” skills?

The primary traditional skill of a lawyer is applying the law to solve problems. Almost every lawyer develops a range of related skills (see below) that can also be useful beyond simply providing legal advice.

Traditional skillset

A lawyer develops skills that can be used beyond providing legal advice. For example:

- Problem solving;

- Analytical;

- Communication;

- Persuasion/Advocacy; and,

- Negotiation.

However, are these skills sufficient? One way to answer this question is to look at the type of work that in-house lawyers are now doing and might do in the future. Everyone’s situation is different, but it is possible to make some general observations on how work is evolving for many in-house lawyers.

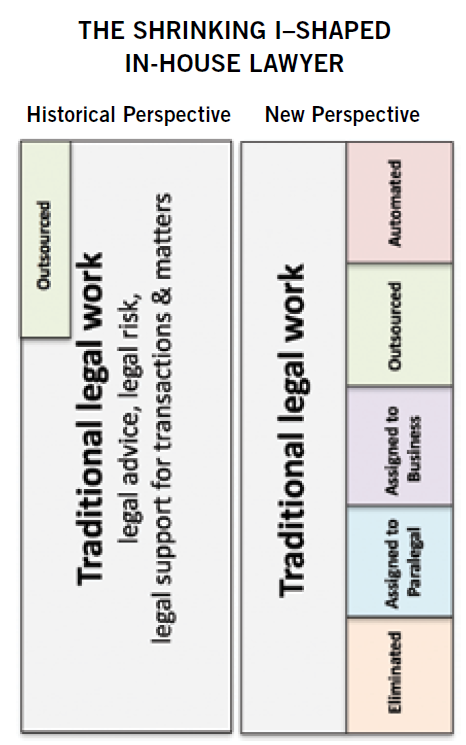

In some instances, the work traditionally performed by in-house lawyers is shrinking due to factors such as empowering the business to self-help, assigning work to contracts managers and others, outsourcing to firms and other service providers, or automating work. For some lawyers, this evolution, especially the advance of technology, might be worrying. However, much of the “displaced” work is low value work — which can be a positive development if it frees you to do additional higher value, varied, and interesting work.

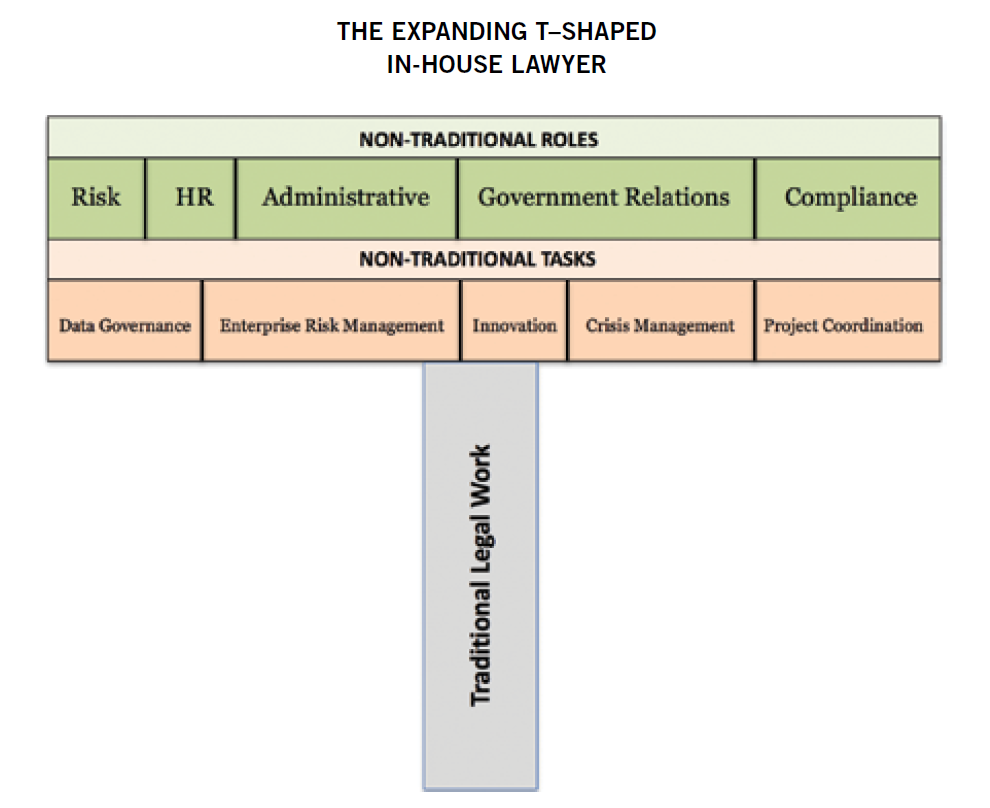

On the other hand, as shown in the graphic below, the type of work performed by some in-house lawyers is expanding as they take on nontraditional tasks and responsibilities.

For example:

- GCs are assuming new roles in the company. “There is little argument that today’s GC has a much wider purview beyond the customary responsibilities as chief legal officer.” The GC is now “a more strategic business advisor”* and sometimes assumes additional roles such as human resources, risk, and government relations.

- New roles being created in the legal department. You only have to look at firms and some larger legal departments to see a trend in new full-time or part-time roles for lawyers and others in areas such as operations, project management, innovation, process, technology, and data analytics.

- New tasks for all lawyers. Progressive in-house lawyers at all levels are informally doing more than providing legal advice. They actively seek opportunities to partner in all areas of the business and, in particular, in areas such as data governance, crisis management, government affairs, and enterprise risk management.

* “Beyond the Law: KPMG’s global study of how General Counsel and turning Risk to Advantage” 1, 51 (2012)

In addition to the changing roles and tasks that will result in in-house lawyers doing more non-legal work, there are a number of other significant trends which are relevant to the skills that will be needed. For example, in-house lawyers will increasingly:

- Work more collaboratively with internal colleagues who are not lawyers to address business challenges over and above providing legal advice;

- Be required to choose between a vast range of new and different legal service and product providers and then be able to work effectively with them;

- Need to be able not only to use technology, but also apply and provide it for the benefit of business colleagues; and,

- Be expected to innovate not just for the legal department, but also for the company as a whole.

It is quite obvious that traditional legal skills will not be sufficient for these purposes. According to PayPal General Counsel Louise Pentland, legal training is no longer exclusively sufficient for in-house counsel. “The high-potential people in my team are able to work in parts of the business that call on different skills.”

This requirement for different skills becomes more critical the further you progress in your career because, oftentimes, the more senior you become, the less time you spend advising on the law. However, junior lawyers would also benefit from developing non-traditional skills, in addition to traditional skills, early in their career. If they do, especially in areas such as technology, they may be able to make more of an impact on the department and in the organisation.

What new knowledge, competencies, and experience are important?

In this new normal, in-house lawyers will benefit from not just “non-traditional” skills, but also greater diversity in knowledge, experience, and competencies. This is mostly obvious, but before focusing on skills, I will briefly mention a few salient points.

Knowledge of the law has always been the bedrock for lawyers. Whereas lawyers working in law firms tend to specialize, many in-house lawyers benefit from a more general knowledge of a range of legal areas — especially if they aspire to a GC position. Also, in an increasingly global business world, it helps to develop a global understanding of the main legal areas that impact the business of your company — at least to a level to be able to “spot issues” and then seek more specific guidance when necessary.

Business knowledge and, in particular, knowledge about the business of the company you work for, is important for in-house lawyers in order to provide effective traditional legal support. This knowledge assumes greater importance as you do more non-traditional legal work.

Knowledge about technology is the other major area that is now crucial and will become increasingly more important with modern advancement. Most in-house lawyers are reasonably competent at using the basic technologies relevant for their work. However, you also need to enhance your overall technology IQ and be able to make informed decisions about what technology to acquire, develop, or leverage.

Integrity and judgement have always been critical competencies or qualities for in-house lawyers. However, in times where there is a premium on innovation and collaboration, other competencies — like empathy, foresight, adaptability, resilience, creativity, and emotional IQ — become increasingly important.

It will come as no surprise to hear that diversity of work and life experiences will provide you with unique insights and skills that you can apply to your in-house work. As former AB InBev General Counsel Sabine Chalmers suggested: “move out of legal altogether and go into investor relations, sales, or M&A. Working in a different geography is also very helpful.”

What non-traditional skills are important?

In selecting the skills to include in my Everything But The Law™ training program, the best reference point was my own experience as an in-house lawyer. The skills listed in the graphic below are the ones that, more so than others, really helped me to innovate, collaborate, and add significant value over and above providing legal advice. Learning how to do these things will help you become a T-shaped lawyer.

Below is a brief explanation of these non-traditional skills and an indication as to why they are important for in-house lawyers to implement.

Process improvement

A process is any sequence of events with a start and an end point and a series of actions and decisions in between. Most of what you do can be reduced to a process. Engaging outside counsel or putting a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) in place with a customer are examples of processes.

Process improvement is about continually reviewing and optimizing a process. There are different process improvement methodologies ranging from simple process mapping to Lean and Six Sigma. Process improvement might sound very industrial and perhaps ill-suited to what many lawyers believe to be an artisanal practice like law. However, if you learn how to use it, you can:

- Help address problem areas and identify activities that the legal department should start or stop doing;

- Collaborate with business colleagues to improve business processes and, at the same time, transfer ownership of tasks that should not be done by lawyers; and,

- Lay the essential groundwork prior to the adoption of any new technology.

Project management

Project management and process improvement are often incorrectly used interchangeably. They are related but distinctly different skills and have different uses.

The best way to explain the difference is with an example. When a company acquires another company, it is a major undertaking or a project. To achieve an optimal outcome, it requires cross-functional collaboration and coordination to provide various deliverables on time and within budget. Project management refers to that coordination in relation to that project. Each acquisition may have its own unique considerations, but a company can define an optimal process, with variations, to follow every time it acquires another business. Over time, it can refine and improve that process.

Confusion can also arise when law firms stress the importance of legal project management because, from their perspective, most matters are viewed as a project. Much of what you do as an in-house lawyer would not qualify as a project. However, some transactions, including disputes or initiatives, do require project management. If you have the time and ability to project manage, it is an excellent way to collaborate with your colleagues and show business leadership.

Design (or creative/innovative) thinking

Design thinking is becoming a critical new skill in the business world. It is best known as an iterative process, involving regular feedback that anyone can follow to rapidly develop products and services that meet a user’s real needs.

Lawyers are also starting to experiment with it. For example, when I was working in-house as head of global compliance a few years ago, I led a design thinking workshop to tackle the well-known problem of providing corporate employees with engaging online compliance training. I observed first-hand how it facilitated a reframing of the problem, which resulted in the development of a breakthrough video product that I now market.

Of all the different business and legal-specific innovation concepts, design thinking is particularly useful for lawyers because it helps you to see familiar problems in new ways through the eyes of your clients. It can be used for collaborative innovations, but also for presentations, contract drafting, and providing advice on an everyday basis.

Business partnering

Being viewed by colleagues as a business partner or trusted advisor is something that most legal departments rate very highly. But in my work helping departments all over the world, I am often told that business partnering is not a skill but rather just “something we do.” That probably explains why, despite its undisputed importance, very few legal teams have received training on business partnering. As a result, lawyers working on the same team often have a completely different understanding of what it means. Some instinctively do it. Others have concerns and don’t do it at all.

I believe that if you treat business partnering as a skill, and spend time on developing it, then it enables every lawyer to collaborate with their business colleagues to enhance their value over and above providing legal advice.

Business leadership

Business leadership is really an advanced form of business partnering with a few fundamental differences. First, unlike business partnering, you need to create and invest additional time in business leadership initiatives. Second, it invariably requires a more strategic focus and an ability to lead a cross-functional team. Third, and the reason it is such an important skill, is that it can provide an opportunity to innovate and make a significant business impact.

Like everyday business partnering, business leadership is a skill that needs to be developed. General leadership training will help, but there are many unique considerations for an in-house lawyer to identify a business leadership opportunity, then collaborate with and lead their business colleagues.

Risk management

It is often said that the primary role of a lawyer is risk management. Despite it being so important, very few in-house lawyers have received any formal training or guidance on the topic. The result is often an inconsistency in advice between lawyers on the same team, as well as a missed opportunity to add value.

Risk management is a critical skill for in-house counsel for a number of reasons:

- If it is understood that risk identification is just the first in a multi-step process, then it can truly aid optimal business decisions.

- If you apply risk management to all types of risks, not just legal risks, then you can enhance your value.

- Risk can and should inform what work you decide to do and how you decide to do it.

- Risk is one of the most crucial levers for innovation in the legal department.

Technology

Enhancing your ability to use technology for efficiency is a frequently discussed and important skill. Technology can also offer opportunities to innovate if you know how and when to adopt technology for the legal team and/or your business colleagues. To do that requires a consideration of many different factors and a new set of skills. Some of these are touched on in the article “Will law firms become software companies — the implications for in-house lawyers.” These skills include the ability to:

- Decide whether technology is the best solution, or whether process improvement will suffice;

- Prioritize and define your technology needs with a technology plan or roadmap for your department so that technology decisions are based on a strategic process and not on a reaction to vendor pressure;

- Develop and implement a data plan to capture operational and knowledge data in a structured way;

- Identify and repurpose existing technologies used by the company;

- Decide whether to make or buy software;

- Write software code (although this is not an essential skill for all lawyers as explained in this article);

- Manage the production of software in appropriate cases using internal and/or external resources;

- Select and work with the most appropriate third party vendor and/ or consultant; and,

- Hire and manage tech-savvy team members (who may not be lawyers) where appropriate.

Connor, Peter. ACC Australia Journal March 2017.

Few lawyers have the above skills and related experience. Some might ask: “How difficult can it be? I’ll just figure it out.” But it is easy to get technology adoption wrong, and the consequences can be significant. At best, it will mean a waste of time, money, and effort. At worst, it can create problems for the legal team and for any work colleagues who use the technology. The prudent thing to do is to enhance your skills in the above areas through training and/or guidance from those with relevant experience.

Change management and leadership

It is important to remember that using these new skills — and any innovations that arise as a result — involves change both for the legal team and for your business colleagues. Learning how to apply change management principles maximizes your chances of turning great ideas into lasting change.

Leadership has always been important. However, in times of change, it becomes a lot more challenging. Many of you will have had leadership experience and training. However, rarely does that experience or training prepare you for new leadership challenges such as:

- How to create an inspiring vision that represents a clear picture of the change you want your team to make;

- Preparing an innovation plan as opposed to making ad hoc changes; and,

- Leading a cross-functional virtual team.

It is important to continue to refine your leadership skills so that you can not only manage the changes happening in the legal industry, but also lead change for the legal team and for the company.

Where can you source training on these non-traditional skills?

In-house lawyers have historically sourced training from law schools, law firms, legal conferences, and the internal training provided by your company.

With some notable exceptions in North America, law schools around the world have been slow to respond with changes to their undergraduate and postgraduate curriculum to meet the demand for non-traditional skills and knowledge. As a result, the best that law students can do is to include relevant and available general business and technology subjects in their courses.

Law firms will continue to provide robust training programs on traditional skills for lawyers fortunate enough to work for the firm. Firms also provide valuable legal updates for in-house legal departments. Progressive firms are starting to extend the scope of this training, beyond legal knowledge and skills, in an attempt to retain an ongoing and relevant training support role. The challenge for firms is that, for many of the reasons raised in the first section of this article, there is an ever-widening “gap” in the way that in-house and law firm lawyers work. As a result, traditional law firms don’t have the same need for, or relevant experience in, applying non-traditional skills. However, recently some firms have started hiring external trainers to provide training on some non-traditional skills for clients as well as their own employees.

The major challenge for legal departments, as well as the traditional training providers, is finding someone who not only understands these nontraditional skills, but also has relevant experience at applying the skills as an in-house lawyer. If you can’t find someone with that experience, then the next best solution is to find someone who can at least teach you the theory. You can, as I did, learn how to apply the skills on the job through trial and error.

Conclusion

There is a lot of negative talk in the press about job prospects in the legal field and it may be that “traditional” legal roles in traditional firms and departments are in decline. However, by taking steps to develop and apply critical non-traditional skills, you will, as much as possible, insure yourself against whatever changes may come your way in the future. By becoming more creative, innovative, and collaborative with your business colleagues, you will ultimately add value for your organisation. At the same time, you will increase your marketability and do more varied and interesting work. This is also how you can become a T-shaped lawyer.

By taking steps to develop and apply critical non-traditional skills, you will, as much as possible, insure yourself against whatever changes may come your way in the future.