Banner artwork by Paul Craft / Shutterstock.com

“Humankind has survived thus far because we can work well together, communicate, empathize, anticipate, understand, and exchange,” Idris Mootee wrote in his book Design Thinking for Strategic Innovation. Design thinking (and legal design) reflects these abilities, and the culture behind these processes and practices. Legal design is gaining momentum but is not always well understood.

By improving the readability and utility of documents and contracts, in-house lawyers help their organizations become more efficient, better serve customers, and benefit society.

I discuss legal design with Laura Hartmann, general counsel for Grampians Health, and Sara Rayment, principal legal designer at Inkling Legal Design. What does legal design really mean? What characteristics do we need to cultivate, and how can we start?

Why we need legal design

Helena Haapio and Stefania Passera argue in Contracts as Interfaces that today’s contracts don’t work as well as they should. They cite surveys by the International Association for Contract and Commercial Management that “reveal that the vast majority of business people find contracts hard to read or understand and that current contracts are of little practical use to delivery teams and project managers. When it comes to usability and user experience, contracts are well below the standard people have come to expect from anything else they work with. In terms of style, contracts do not support cognitively-overloaded, busy readers in searching, integrating, and understanding the information they contain.”

They argue that good contract design is not only about the right content, it is making sure the message is understood through the harmony of technical, operational, financial, legal, and communication expertise. Legal expertise is just one piece of the puzzle.

Hartmann says she is "fascinated by processes and systems. I’ve long been curious about what drives some of the problems that in-house teams seem to encounter over and over again. While every legal team is unique, we seem to share different versions of the same challenges.

"Legal design provides a tool kit for thinking differently about those problems. Most importantly, it challenges the traditional legal model of very top down, hierarchical, formal approaches to our work. It places our stakeholders at the center of everything we do and helps us to understand a legal task from their perspective.

"The positive purpose of legal design is to connect lawyers with the people who need our services. It brings empathy back into legal processes, and also provides an opportunity for creativity and play in an otherwise very rigid profession.”

What is legal design?

Hagan’s Legal Design (Law By Design)

Hagen describes legal design as:

- The application of human-centered design to the world of law, to make legal systems and services more human-centered, usable, satisfying, and a way to generate ideas for how legal services could be improved, and developed in quick and effective ways;

- Bringing a culture of design thinking, user research, and human-centered design methods into the world of law. And in the process, setting key new metrics — are we delivering services that are

- Usable,

- Useful, and

- Engaging which help both the lay person and the legal profession.

- Furthermore they should offer:

- Improved problem solving,

- Client focusing to deliver better services,

- Making complex legal information clear,

- Building new pathways for lawyers,

- Improving ways to collaborate, improve processes, decision-making, and

- Generating ideas (using technology or otherwise) into viable products and businesses.

Mootee’s Design Thinking for Strategic Innovation

According to Mootee, design thinking:

- Includes a way to take on design challenges by applying empathy, curiosity, and is “the search for a magical balance between business and art, structure and chaos, intuition and logic, concept and execution, playfulness and formality, and control and empowerment;”

- Is about cognitive flexibility, the ability to adapt the process to the challenges; and

- Involves the key principles of action (actually experimenting and doing), being comfortable with change, being human-centric, being iterative and continuously learning, promotes empathy, reduces risk by considering all factors, creates meaning, and fosters a culture that embraces questioning, inspires frequent reflection in action, celebrates creativity, embraces ambiguity, and creates strong “inspirationalization” and “sensibility” to give tangibility to the emotional contract that employees have with organizations.

This resonates with Hartmann who thinks that, at the heart of legal design, “The law is there for people. Somewhere along the way, we’ve managed to create a bewildering, formalistic, intimidating system that is disconnected from those who need it most. Legal design is the means by which lawyers can look at their system and ask, why is this the way it is? How can I do better? How can I connect this person with their rights? In legal design, you often hear that our purpose is simply ‘to make law better.’”

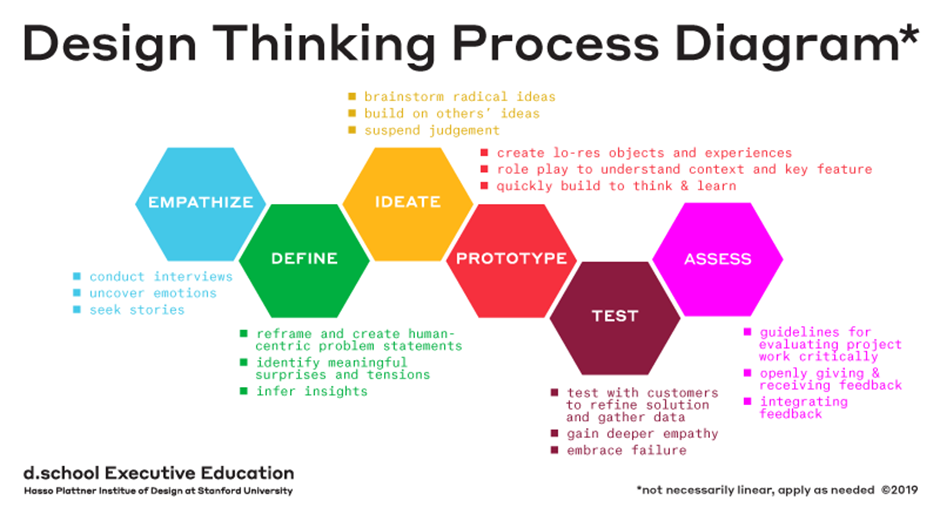

Stanford D. School’s Design Thinking Process Diagram

A well-known illustration of design thinking is the Design Thinking Process Diagram.

[Source: https://empathizeit.com/design-thinking-models-stanford-d-school/]

Legal design is the means by which lawyers can look at their system and ask, why is this the way it is? How can I do better? How can I connect this person with their rights?

Stanford D. School’s, An Introduction to Design Thinking Process Guide, explains each of the steps in more detail:

- Empathize — Seek to understand people, within the context of your design challenge, because the problem you are trying to solve is rarely your own. Empathy also helps come to a problem with a “fresh pair of eyes.” For Hartmann, empathy and keeping an open mind are critical mindsets needed for legal design.

“I’ve seen firsthand how confronting some lawyers find the idea of speaking with stakeholders, or even the public, about how engaging with a legal process makes them feel. It’s something we tend to run a mile from,” she says. “But stakeholder insight is worth its weight in gold, and the means by which we build empathy with our organization. We can’t design solutions without properly understanding the problem from our user’s perspective.

"I’ve found that the problem is often not what we expect. For example, we recently tested some letters with members of the public and had an overwhelmingly negative response to the word 'valid.' For lawyers, the word is completely innocuous, but for our test group, it was like a red rag to a bull!”

- Define — Identify the challenge you are taking on based on what you have learned about your user and about the context.

- Ideate — Generate ideas and transition from identifying problems to creating solutions for your users. Finding the best solution comes later, through user testing and feedback.

- Prototype — Create low-resolution prototypes that are quick and cheap to make (think minutes and cents) but elicit useful feedback from users and colleagues. Refine it later.

When asked how she deals with the iterative approach to legal design and whether it needs a mindset shift away from perfectionism, Hartmann says, “This is so hard for lawyers! We naturally default to wanting only one solution and making sure it’s the best from the get-go. I think that’s where rapid prototyping can be invaluable.

"Rapid prototypes let us test something cheap and easy very quickly. We can feed our perfectionist mindset by allowing for some iteration along the way, i.e., ‘I need to break this now so that I can get the best solution later.’

"But taking that first step of putting something out there to test, which isn’t perfect, can be quite challenging. We’re just not wired that way. That’s why it’s really important for leaders of in-house teams to embrace and encourage failure. The best iteration comes out of an environment where failure is no big deal. You can’t iterate in an unsupportive team, or ‘blame’ culture.”

- Test — Ask for feedback about your prototypes. Hartmann says: “Always prototype as if you know you’re right, but test as if you know you’re wrong.”

When asked how she brings stakeholders along the journey with her for design projects, Hartmann answers, “I include stakeholders in all my projects, in different ways. For our recent Freedom of Information (FOI) automation project, we had FOI reviewers and our FOI admin on the build team. They found so many practical, real-life issues that I would have otherwise overlooked with my 'lawyer' hat on. For an upcoming contracts project, we’ll look to have stakeholders test and give feedback later in the process.”

- Assess at the end of a project.

It's really important for leaders of in-house teams to embrace and encourage failure. The best iteration comes out of an environment where failure is no big deal.

Legal design in action

Looking for some examples of successful legal design? Try some of these:

- In Layered Contracts; Both Legally Functional and Human-Friendly, Waller, Passera, and Haapio set out different visual examples of ways to present contracts including order forms, and how to set out contracts with different architectures;

- Robert de Rooy of Creative Contracts created an innovative way of drawing up employment contracts using cartoons because of seasonal agricultural workers with limited reading experience; and

- Logistics software company Juro created a simple privacy policy following the introduction of GDPR.

Hartmann has been invited to present a project as part of a panel on "Innovative Thinking in Legal Design," at the upcoming International Legal Design Summit.

“I named it the Gladys project,” she says, “I name all of my projects after people. The reason is very simple — to keep in mind that they are the ultimate end user of my work. It's easy to get lost in the legal side of a project, but when you have “Gladys” or “Russell” coming up in your calendar, it is very hard to forget! Gladys is a persona I created to underpin our Freedom of Information project. So, all of our letters, documents, and the wording we use in the automation come from Gladys’ voice. I created Gladys based on demographic data my organization already held — so our letters are written in plain language in a way that the persona would write them, etc.”

What characteristics do we need to be good designers?

Legal design requires us to cultivate characteristics not always associated with lawyers — empathy, collaboration, and the ability to use technology to make legal design interactive and more accessible. However, we also need creativity, because legal design needs convergent and divergent thinking. We need divergent thinking to come up with lots of ideas and then convergent thinking to bring them all together into a single solution. For ways to cultivate your convergent and divergent thinking see my previous article.

In Mapping Legal Innovation, Mason and Robinson said, “Creativity and innovation are increasingly recognized as keys to success in professional contexts … most legal professionals seem to recognize the role creative thought plays in aspects of their work.” Their approach to overcoming conceptual creativity blocks?

The Creativity Profiler, a state-of-the-art, multi-dimensional assessment tool, of research-based tests measuring all the most important characteristics for identifying and measuring creativity and creative potential in different fields and professions.

All four major kinds of “resources” that can contribute to creative performance — cognitive, conative (more personality-related), emotional, and environmental resources — can be measured and explored using the Creativity Profiler. In addition to discussing divergent and convergent thinking, they also consider emotional characteristics play an important role in creativity.

A key example in this instance concerns the paradoxical role often played by empathy in the legal profession. Legal thinking and problem-solving call upon high empathetic capacity and strong “theory of mind” related skills (e.g., when predicting an opponent’s reactions or judging the common interpretation of legislation or impact it will have on society.)

Creativity is crucial to legal design and is a mindset shift for some. Hartmann thinks the greatest challenge for in-house lawyers trying to embrace legal design is “mindset.”

“Early in my design journey I had a really terrible experience with lawyers reacting badly to the very premise of legal design," she remembers.

"On reflection, I think that is a product of the way that lawyers are trained. Doing things differently in a system based on precedent is inherently confronting. Culturally, lawyers find it extremely hard to be ok with the inherent ambiguity in legal design and embrace the possibility of failure. We’re not very good at the idea of failing, but it’s such an important part of the design process! It’s also very hard to justify using scarce resources to approach things in a different way, especially when you want to get some level of failure in it! The lawyers I’ve met in this area tend to be very creative and are curious, lateral thinkers. Legal design seems to find a home with people who ask ‘Why?’ relentlessly.”

When asked what part creativity plays in her process, Hartmann says, “Creativity is essential in any design process. I use lots of butcher’s paper and a pencil! I’ve always been a bit of an out of the box thinker, so I love thinking of the most ridiculous solution possible and then seeing what is realistic to unpack from that. My friend Sara Rayment has a great prompt table that helps generate ideas, e.g., AU$5 ideas? AU$5 million ideas etc.”

Not all lawyers can, or even want to, find this creativity. Some may want to partner with legal designers. But how to get the best out of this relationship? I spoke with Rayment.

Getting the best out of your legal design partnership

After meeting the teams that designed eBay’s ODR system and IBM’s Watson artificial intelligence team, Rayment realized, “We finally had the ability to scale legal services but not necessarily all of the skills required to do so effectively. How can we help lawyers, technologists, entrepreneurs, and government work together to achieve this? We needed a common language and process. That’s where legal design comes in. Design-thinking had already been used successfully in many other industries to bridge the gap between diverse groups. Legal design is design-thinking with a legal lens. It helps lawyers work with others to solve legal problems in a holistic way.”

Rayment’s tips on work that can be done with a partnering with in-house legal teams:

- Simplifying terms and conditions or B2B contracts using visual law;

- Redesigning internal procedures and conducting fitness for purpose testing;

- User testing assessments for privacy policies and data breach responses to identify reputational risks and areas for improvement to the response;

- Designing the legal advice process and templates to help in-house teams cut through the noise and drive engagement;

- Designing visual law templates and tone of voice guides for simplified legal communications; and

- Chatbot conversation design and flows.

Legal design is design-thinking with a legal lens. It helps lawyers work with others to solve legal problems in a holistic way.

Rayment identified “openness” as the characteristic needed for successful collaboration. “As lawyers, we tend to be deeply skeptical, and this militates against important skills like suspending judgement and being curious. We have a tendency to shoot down ideas and bury creativity before it has a chance to emerge. There is a lot of deprogramming that happens in a design sprint which can cause discomfort. People who are more open tend to experience this less. It’s important to understand that just because a person is low on openness it doesn’t mean they will be bad at design. It just means they are likely to find it more challenging than those lawyers who are high on openness. We usually find that lawyers enjoy having permission to draw on their broader skills and creativity. Most lawyers are actually quite creative. They’ve just never had a reason to incorporate it into their practice before and law is such a challenging career they often don’t have time for it anymore. In that way, legal design is quite restorative. It allows lawyers to bring more of themselves to work and incorporate their experiences in a meaningful way. That’s where we see broader changes, because these lawyers realize that legal design isn’t just a project, it’s an entirely different way of practicing law.”

Takeaway tips

Start your legal design journey now with these tips:

- Growing a creative mindset away from perfectionism — Hartmann says “Building a culture of trust, empathy, and play in your team. It is essential to create a space where anyone can have an idea and feel completely supported to crash hard with it. That’s essential to fostering creativity. But also encouraging lawyers to find ways to connect with the business and ask the hard questions that we don’t really want to hear the answers to. For example, “How did reading that contract make you feel?” “What could we improve about our process?” “Why?” And asking “Why?” enough times to actually get an answer, not just the answer that your stakeholder will tell you to make you feel good or get you to go away. And asking it in person, not an email.”

- Start doing legal design work — Hartmann says, “Just start! Don’t wait until you know how or perfectly understand the double diamond etc. Pick a small project and see it through. Do some process mapping or have a coffee with a stakeholder to get their thoughts on X process. You don’t have to change the world in your first project.”

- Workshops — Hartmann suggests trying workshops like Inkling Legal Design’s “Unconference,” which is first steps in design for in-house lawyers. “I highly recommend that day as a way of opening your mind to the possibilities of legal design” and reading books like Peter Butt’s Modern Legal Drafting.

- Start small suggests Rayment. “A small but successful change will make a big difference," she says. "There is so much potential to apply legal design, it can be overwhelming to decide where to start. It’s also an attractive form of innovation because it can be applied directly to legal work without using technology and that is a rare opportunity for lawyers.

"For legal information, playbooks, short contracts, and terms and conditions are a good place to start. For processes, the provision of legal advice or retention of external counsel are also great areas. For busy teams, we usually suggest targeting a project that will reduce the burden on the team’s capacity. This might be a self-serve tool or playbook which reduces the number of escalations to the legal team.”

Disclaimer: The information in any resource in this website should not be construed as legal advice or as a legal opinion on specific facts, and should not be considered representing the views of its authors, its sponsors, and/or ACC. These resources are not intended as a definitive statement on the subject addressed. Rather, they are intended to serve as a tool providing practical guidance and references for the busy in-house practitioner and other readers.