Banner artwork by solar22 / Shutterstock.com

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”

Philosopher Will Durant paraphrasing Aristotle

It’s late in the evening, and you’re struggling to finish the draft emails you’ve been meaning to send to your outside counsel for days. But you keep getting distracted — you check your social media, your personal email, your sports team’s score. Why is it so hard to turn away and focus?

What if our habits are hijacking the very thing that drives our excellence: our attention. We often feel that we are no longer in charge of our own attention. But who is? Jonathan Hari’s book, Stolen Focus, identifies technology as the culprit, stealing our attention in a way that undermines even the benefits of a short-term digital detox. Our lives are inextricably intertwined with technology — at work, at home, in the car, and on holidays. But how have our digital devices subtly persuaded us to make choices like buying things we didn’t realize we need or even want, to the point that they have stolen our focus and rewired our brains. The answer is — captology.

Captology, an acronym for “computers as persuasive technologies,” coined by Dr. B.J. Fogg, refers to how technologies (computers, websites, phones, apps) can change behaviors by combining traditional methods of persuasion together with the new capabilities of devices.

As Johnson and Ghuman say in their book, Blindsight, “Our time is money. The longer a site or app can keep you online, and the higher your engagement, the more advertisements it can sell.”

The longer a site or app can keep you online, and the higher your engagement, the more advertisements it can sell.

Computers weren’t created to persuade us — they were created to handle data. So how did technology become a tool for persuasion, and why does it seem to suck us into a vortex of never-ending cat videos? What can we do to regain some of that focus and take charge of our lives?

The origins of captology

Fogg, in his book, Persuasive Technology, described captology as the intersection between technology and persuasion which “focuses on the design, research, and analysis of interactive computing products created for the purpose of changing people’s attitudes or behaviors.” Fogg and the former Persuasive Technologies Lab at Stanford University built on B.F Skinner’s work.

In 1930, Harvard University philosopher B.F. Skinner found a way to get rats and pigeons to do what he wanted by offering the right reinforcements of their behavior. Skinner was a proponent of ‘behaviourism,’ the premise that behavior is best understood as a function of incentives and rewards.

Hari described how two of Fogg’s students, Tristan Harris and Mike Krieger designed an app called “Send the Sunshine” to help with seasonal affective disorder. The app connected two friends and tracked their local weather. If the app realized your friend didn’t have sunshine and you did, it would prompt you to take a photo of the sunshine and send it. Krieger and another student, Kevin Systrom, created another app using Skinner’s suggested positive reinforcement that shaped the user’s behavior by making sure they received a heart and ‘likes’ right away — this app was Instagram.

Harris later worked on the Gmail app at Google, noting that it dizzyingly stole his attention as he obsessively checked his emails. This technology works on engagement. The more time we spend engaged with an app, the more chance we get to see advertising or be prompted to buy something after following a few links.

But how has technology made us more distracted, and how is it focusing our attention where it wants to? Fogg’s model shows us.

The Fogg Behavior Model

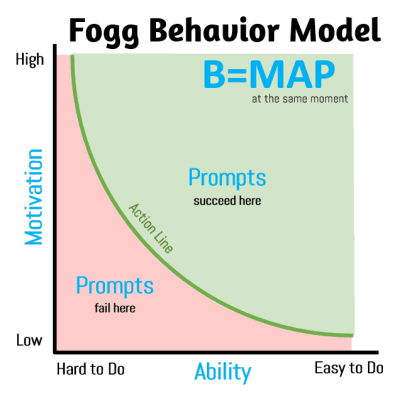

In 2007, Fogg created the Fogg Behavior Model:

B = MAP

The model shows that "Behavior (B) happens when Motivation (M), Ability (A), and a Prompt (P) come together at the same moment."

Motivation

The more motivated you are to change your behavior, the more likely you will do it. There are a few core motivators:

- Sensation (pleasure/pain) — responding to what’s happening in the moment

- Anticipation (hope/fear) — believing that something good/bad will happen

- Social acceptance/rejection — being motivated to do things that will win social acceptance, status, and avoid any negative consequences leading to being socially rejected

Ability

You must have the ability to do the behavior. The easier, the better. There are five sub-components:

1. Time — the less time the more likely you will do it

2. Money — you must be able to afford to take a certain behavior

3. Effort — new behaviors should take minimal (a) mental effort, and (b) physical effort

4. Social deviance — behavior should not go against the social norm

5. Routine — make it easy to change the behavior by tying it to something you are already doing

Prompt

There must be a prompt or call to action. Fogg divides these into three triggers:

- Spark — high ability but low motivation

- Facilitator — high motivation but low ability

- Signal — both motivation and ability are high

Technology designers use Fogg’s model. For example, a streaming service automatically plays the next episode of a show unless you tell it to stop. A viewer is persuaded to keep watching. The Economist’s 1843 magazine describes this as — you want to keep watching (motivated), you can do it (in fact you do nothing if it plays the next episode), and the trigger is the start of the next episode. This dopamine fueled cycle keeps us watching the next show or falling down the rabbit hole of social media scrolling.

This dopamine fueled cycle keeps us watching the next show or falling down the rabbit hole of social media scrolling.

How we became even more hooked

Nir Eyal, another early Fogg student, worked for some of the most influential Silicon Valley companies and wrote the book, Hooked, teaching how to build habit forming technologies to keep us coming back until we are “hooked.”

Building on the Fogg Behavior Model, his work requires a trigger; the ability to act; a variable reward; and an investment. He suggested creating internal triggers, targeting negative emotions such as boredom, loneliness, or the fear of missing out. The desire to be entertained, which seems positive, is simply an attempt to stave off boredom, and users who find a product that alleviates their pain will form a strong, positive association with it.

The desire to be entertained, which seems positive, is simply an attempt to stave off boredom, and users who find a product that alleviates their pain will form a strong, positive association with it.

Then there is the infinite scroll. Created by Aza Raskin, it is now used by all social media sites and doesn’t give people a natural stop to move away from the device. Raskin told Hari he calculated that “at a conservative estimate, infinite scroll makes you spend 50 percent more of your time on sites like Twitter.”

In the Tech4Evil podcast’s three-part series on captology, hosts Manal al-sharif and Reinhardt Sosin further illustrated Eyal’s method: the trigger is the notification, the action is checking your phone, the reward is the likes you get, and the investment is you commenting and posting more. They went on to describe that, “once a habit is formed, the external stimulus that previously promoted the habit, like a notification, is no longer needed. It can be replaced or supplemented by an internal trigger.”

The art of getting unhooked

Nir Eyal later wrote a book, Indistractable — How to Control Your Attention and Choose your Life, teaching people how to become unhooked from apps and devices.

Disrupt your internal triggers

- Understand the root of your distraction by looking for the emotion that precedes the distraction. Write down the internal trigger and explore the negative sensation with curiosity.

- Identify if you feel bored or stressed while working and start wanting to google things that have come into your mind. Write down what you want to check. Later, when you have finished your work, look at your notes and go online to find the answers.

- Be cautious during transitional times of day between activities (e.g., you open a tab in your web browser, get annoyed by how long it’s taking to load, and open another page while you wait). Eyal says that by doing them ‘just for a second’ we’re likely to do things we regret later, like getting off-track for half an hour. He suggests the ten-minute rule: “If I find myself wanting to check my phone as a pacification device when I can’t think of anything better to do, I tell myself it’s fine to give in, but not right now. I have to wait just ten minutes … this rule allows me to do what some behavioral psychologists call ‘surfing the urge’ — when an urge takes hold — noticing the sensations and riding them like a wave — neither pushing them away nor acting on them — helps us cope until our feelings subside.”

Hacking back your phone

- Changing notifications on your phone so your apps can’t interrupt you.

- Delete apps you don’t need, move distracting apps off your home screen, change the notification settings, and use the Do Not Disturb on the phone.

- I create natural mini breaks by moving apps to the second home screen, so it takes me time to find and open them. I also periodically change the app location on my phone, so it takes me time to find them — even that short additional time can be a break that makes me lose interest.

- I use a black screen and change the settings to make my phone less appealing.

- I don’t check my phone in bed or as soon as I get up, and, while this took a while to become a routine, I look at sunlight and broaden my visual perspective before I check my phone.

ACC Australia’s Legal Technology and Innovation Committee Chair Schellie-Jayne Price leaves her phone at home when she goes out. “I leave it inside the house when I’m in the garden, leave it in another room to enable me to focus — I’m very easily distracted.” She describes a friend “who has a device free zone in her house, demarcated by masking tape on the floor. I also encourage my friends and family to put their phones away when visiting and fully engage in the [in real life] experience.” In essence, the best way not to constantly check your phone is just not having immediate access to it.

In essence, the best way not to constantly check your phone is just not having immediate access to it.

Hacking back your email

- Unsubscribe from emails.

- If possible, have “office hours” on your email, check them only a few times a day.

- Only open an email twice: once to read it and note when a response is needed and a second time to respond. Answer urgent emails and otherwise answer them as tagged. Quickly delete or archive emails that do not need a response. Reply to emails during a scheduled time in your calendar.

- I prefer someone asking me a question at work rather than sending emails back and forth.

Here is another lawyer’s tip for those who are expected to be very reactive on email by their organization: have a separate inbox and divert all non-essential emails (updates, companywide emails, etc.) to that inbox so you can check when you have time.

Price suggests using a “fun ‘out of office’ message to manage expectations about being available all the time like “I’m not able to answer your email because I’m on a cycling, swimming, hiking adventure without my phone” or “I’m having a digi-free weekend. I’ll answer your email when I return to the office on Monday.” Not only is this a great suggestion, but it will reinforce the importance of positive practices to your team and colleagues.

Use your calendar to keep focused

- Plan your calendar to reflect your values and make time in your life for focusing on your values.

- Timebox your day into personal time, relationships, and work so you have a framework on how to spend your time.

Change your environment to support your focus

- Look at your external triggers and know if they serve you — cues in our environments, like pings, dings, and rings from our devices and interruptions from other people, take us off track.

- Interruptions lead to mistakes and open plan increases distractions. Defend your focus by signaling when you do not want to be interrupted. Use a screen sign or some other clear cue to let people know you are “indistractable.”

- Be selective when using a group chat — great for replacing in-person meetings but should not become an all-day affair.

As lawyers, finding strategies to regain time and focus is crucial. Not only does it help us to focus on the necessities of our careers but freeing up time from technology allows us to focus on positive practices like exercising, meditating, and spending time with family and friends.

Disclaimer: The information in any resource in this website should not be construed as legal advice or as a legal opinion on specific facts, and should not be considered representing the views of its authors, its sponsors, and/or ACC. These resources are not intended as a definitive statement on the subject addressed. Rather, they are intended to serve as a tool providing practical guidance and references for the busy in-house practitioner and other readers.