Banner artwork by / Shutterstock.com

Cheat Sheet

- Cash flow is critical. Without adequate cash flow to support the business operations, a business will not be able to accomplish its short- and long-term objectives.

- Boards have the ultimate responsibility. The chief legal officer (CLO), along with the CEO, CFO, and other senior managers ensure controls over (1) cash flow are effective and (2) reporting cash flow up to the board is adequate.

- Cash flows impact capital measures. An analytical model to assist in such evaluations is presented in this article, including basic capital requirements (e.g., working capital and debt service) and market capital requirements.

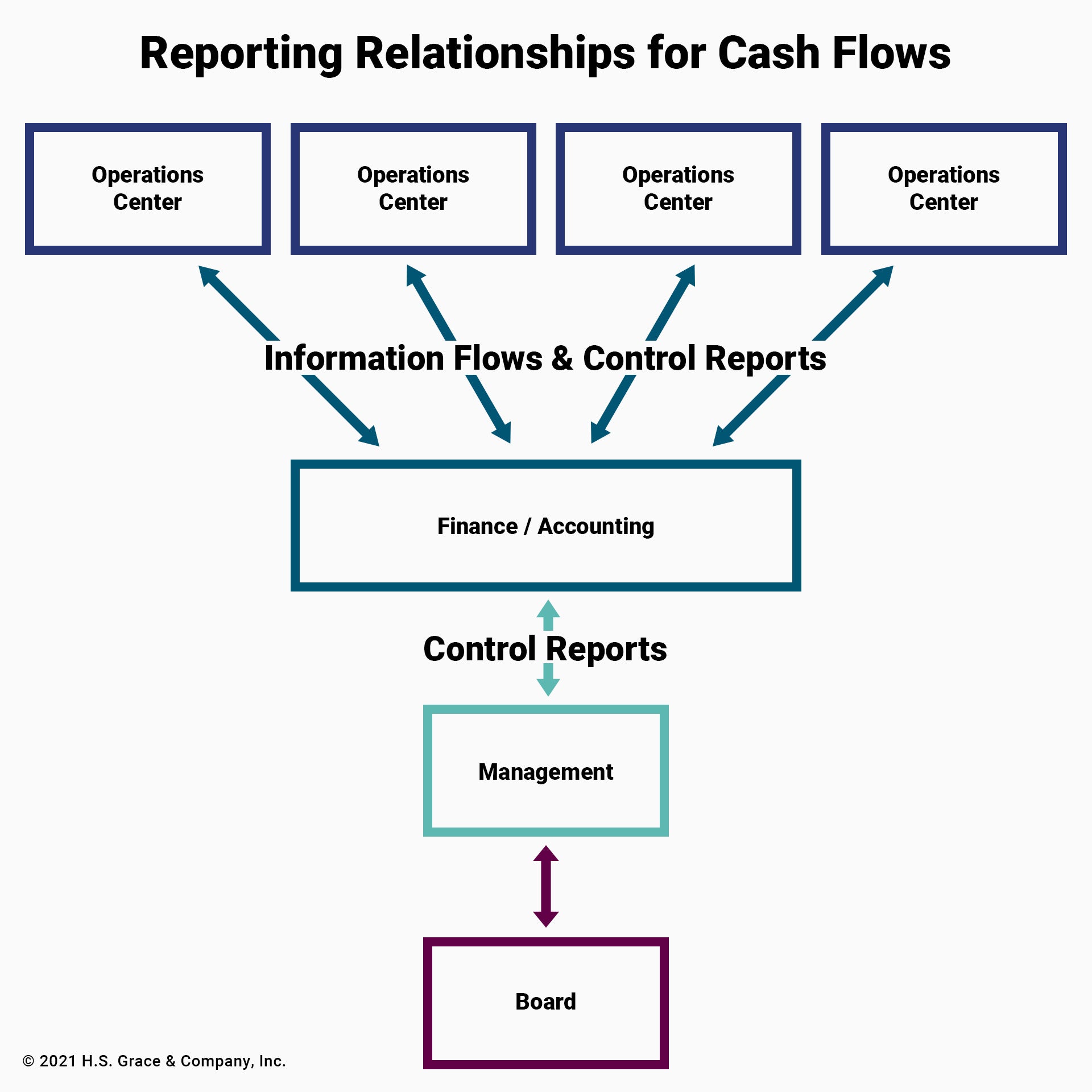

- Monitoring cash flow happens at all levels of the company. The article includes a model presenting reporting relationships for cash flows and related control reports from and to all business units and the board.

Too often the board and management are focused solely on Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) measures, such as earnings revenues, market share, and profitability ratios, with cash management being perceived as a finance or treasury department issue. The ultimate responsibility to manage the business risks associated with cash are no different than all other business risks for which the board has the risk management responsibility.

Today’s business environments continue to evolve with non-controllable and fast moving economic and political changes, such as interest rates, worldwide political turmoil, technology, and other evolving business considerations. Boards must focus on cash and liquidity as critical risks for which they have responsibility.

Responsibility to govern, oversee, and manage cash flow risks

Ultimately, the board of directors has the responsibility for the governance, oversight, and management of cash flows. The CLO has the responsibility of working with the CEO, CFO, and other senior officers to ensure that proper governance, oversight, and management are occurring. For example, in connection with the adequacy of internal reporting to the board regarding the above responsibilities, the CLO should, as a check and balance, assist in ensuring proper focus is placed on cash flows and liquidity at board meetings.

Cash is king

We have all heard the statement: “Cash is king.” Simply stated, without adequate cash to support the business operations, including servicing of debt and capital plans, a business will not be able to accomplish its short and long-term objectives.

Ultimately, inadequate cash resources could lead to an operational restructuring or failure of the business. The adequacy of cash is a business risk that requires the continuing attention of the board and management.

The management of cash and liquidity requires processes, controls, and monitoring which goes well beyond reviewing immediate cash requirements and reviewing bank statements. The reviewing of immediate cash requirements and bank statements procedures relate to just a point in time and are just the beginning of the procedures needed to operate the business and manage the risks associated with the adequacy of cash.

The analytical model of cash flow

An analytical model (Fig. 1) aids in understanding and monitoring operational and capital cash flows. Each business unit that generates cash flow should develop a model to analyze performance. The model identifies basic requirements, such as working capital, capital expenditures, and debt service, and determines if cash flows will be adequate.

If operational cash flows do not provide enough for adequate working capital, do not fund budgeted capital expenditures, or do not cover the required debt service, the business operation is in the “crisis” zone. The options for the business operation are to “fix” or to “liquidate.”

The model also helps manage the risk-adjusted return on equity. When added to the basic capital requirements, this establishes the market capital requirements. As can be seen in the cash flow model, if the operational cash flow exceeds the basic capital requirements but falls short of market capital requirements, the business operation is “underperforming.” While not in “crisis” mode, steps need to be taken to improve performance.

If the operational cash flows exceed the market capital requirements, the operation is in the “performing” zone. This shows an opportunity to invest and grow, pay down debt, buy back stock, or make cash distributions to equity holders.

This relatively simple presentation of cash flow data can give the board a solid understanding of whether the firm generates a positive cash flow and if its cash flow is adequate to meet present and future needs. This ability to monitor whether a firm is generating sufficient cash flow will improve a board’s oversight and control, in good times and bad. A board that understands the components of basic capital and market capital requirements, and how they are affected by cash flows, has considerable insight into the risks confronting the firm and can effectively address its oversight responsibilities.

Controlling cash flow

Controlling the company-wide cash position requires the monitoring of all headquarters, division, and subsidiary bank accounts. Monitoring the headquarters-controlled cash position should be straightforward because the cash management center is in constant communication with the headquarters' accounting staff. Guidelines for maintaining the cashbook on each bank account, handling the support data, and reconciling the accounts are established in accordance with the requisites for internal control.

A basic structure of the process (Figure 2) is set out here.

The internal procedures to determine cash are unique to each company. The cash flow objectives of company boards and management to focus attention on the cash flow risks and the related existence and effectiveness of the cash flow procedures should be relatively consistent across companies. Management must provide timely and useful information to the board, including relevant committees, to fulfill its oversight and management responsibilities.

GAAP vs. cash flow reporting

It is important to understand the cash flow results will be different from traditional GAAP financial statement results. While cash is an easily understood concept, GAAP is viewed by some as arcane, very difficult to understand, and more easily manipulated. Most important, without adequate cash, a company can not survive. There is an example of a public firm that focused solely on the GAAP income statement which reflected having earned US$490 million in one quarter and projected US$525 million for the following quarter. However, the cash flow in the following quarter was projected to be a negative US$475 million, a US$1 billion difference. The firm filed for bankruptcy a few months later.

Most important, without adequate cash, a company can not survive.

Real-life experiences related to the management of cash flow

The balance of this article will focus on the real-life experiences related to the management of cash flows by three members of the Board of Advisors of Grace & Co. Consultancy, Inc. Each advisor’s discussion in this section is intended to provide in-house counsel with practical information to enhance the value they bring to their employer. Where information is public, the names of the parties will be incorporated.

Topic 1: Cash Flow = Fuel that enables diversification, innovation, and growth

Author – Frank R. Gatti - MBA, CPA, NACD Fellow

Introduction

When a board of directors and management develop a long-term strategy to ensure an organization’s sustainability through diversification, innovation, and growth, it is essential that cash flow be an integral component of any plan and its execution. This will ensure that each of the three sustainability components will have the required funding through the most efficient mix of internally generated cash flow and external funding to ensure effective execution. The three examples cited demonstrate the ways in which organizations have focused on cash flow to ensure the achievement of the business and financial objectives that underpin the sustainability, strategy, and the value proposition on which each business case is based.

Diversification

In many instances a component of a strategy is to diversify geographically through M&A in the industry where the acquirer currently operates. In this example, the businesses being acquired were privately held for multiple generations. For several large, long-term customers, this resulted in “informal” payment arrangements with the current owner which resulted in less timely cash flow.

This was uncovered during the due diligence process and required that the acquirer have discussions with such customers to develop a transition plan to migrate them to a payment schedule for current and future services that would favorably impact cash flow and achieve the return on investment that management proposed, and the board of directors approved.

Innovation

In many instances embedding innovation in a strategy is essential to ensure long term viability given the critical role that such investments play. Such initiatives require cash flow to ensure adequate investments in both human capital and technology. An example of this occurred when an organization made the strategic decision to migrate two of its extraordinarily successful global consumer products to online delivery which would enable the addition of new features. Since the content for these two products was already in a digital format, implementation of a secure global delivery network and dedicated sites in 100 countries would be required.

To effectively execute this strategy and ensure adequate cash flow, a multi-year global roll out plan was developed spanning North America, Europe, and Asia. This digital conversion would result in increased revenues through the addition of new capabilities, lower operating costs, and higher operating margins. The internally generated incremental cash flow from the first phase funded the roll out of the second phase, with the second phase doing the same for the third phase. This enabled the execution of this innovation to be funded from internally generated cash flow.

Growth

When an organization’s growth plans involve entering new lines of business, especially when it involves a new category of customers, the timing of cash flow is a crucial factor. An example of this is a case that related to an expansion into renewable multi-year state government contracts. Even though the State’s payments were tied to deliverables, numerous government approvals were required before payments were actually made which put a strain on the timing of cash flow.

When an organization’s growth plans involve entering new lines of business, especially when it involves a new category of customers, the timing of cash flow is a crucial factor.

Given the approaching contract renewal cycle, the organization-initiated discussions with the State regarding the need to accelerate their approval process, while continuing to require that payments be tied to deliverables. The win-win solution that the parties agreed upon was to create a more granular deliverable and payment schedule that would accelerate the State’s approval process and favorably affect the timing of cash flow.

Topic 2: Navigating the slippery slope

Author: Richard A. Schrader, MBA, P.E.

Introduction

When a firm is "in extremis," few options remain for its survival or disposition. By then it would be expected that the general counsel, probably with the advice of outside bankruptcy counsel, would be reminding the board of directors of its duties. Steps forward would usually be carefully planned and executed. Financial distress or crisis management consultants may be engaged to assist the board and executives in how best to proceed and which stakeholders need to be served and prioritized.

But what about the months or perhaps even years before this threshold has been clearly demarcated? What steps would or could have been taken? How much attention was the board paying to potential risks? A comprehensive understanding of the firm's financial condition requires more than standard income statement and balance sheet reporting. In particular, the board should be periodically receiving an appropriate analysis of cash flow and any associated risks to the business. Inattention to cash can lead to a slippery slope or downward spiral from which it is extremely difficult to overcome.

Two examples will illustrate tactical and strategic cash flow issues requiring board and general counsel understanding and action.

Strategic cash issue

An employee-owned firm with stock worth several hundred million by its internal valuation formula faced an increasing number of age-related stockholder retirements as well as normal employee turnover. Stock was held by some 5000 employees in a direct ownership plan and two ERISA plans. Because the stock formula was higher than book value, a significant risk existed in the future that both equity and cash balances would be eroded if pay-outs exceeded new purchases or buy-ins. The then existing five year strategic plan did not specifically address this issue. The issue was identified in a separate risk mapping exercise conducted by a corporate risk management committee (which included three board members) and with the aid of an outside consultant. Their conclusion was that the cumulative impact of a sustained erosion over even a few years would impose severe financial consequences on the firm, possibly threatening its survival as an independent company.

The risk management committee had been established by the board's tasking of the CEO; its composition included legal, financial, and operational executives as well as board members. The board asked for periodic updates from the committee on its analysis and recommendations. This led to a board/management workshop (with consultant) to discuss various options to mitigate this particular risk. Ultimately, a multi-faceted action plan was put into place, vetted by counsel and the CFO as to feasibility and compliance. The CFO would provide periodic updates to the board on progress. When later the firm's bank and insurance consortia also asked about this particular risk, the CFO and general counsel were well prepared to discuss it.

Distress cash issue

Private equity (PE) owned a majority stake of a construction firm with multiple projects for the US and NATO in the Middle East. As war operations wound down, the government agencies slowed payments as audits were increasingly conducted to validate expenditures. Increased security threats to the firm's personnel in the field as US forces downsized led to work stoppages and disputes with the governments over respective contractual responsibilities. The firm's cash flow began to be severely impacted by the slowdown from these changed conditions.

The PE had a year earlier added three independent directors on the board who also comprised the audit committee (AC). The PE and management were making periodic financial reports, including cash flow, but the AC believed such reports should be at a minimum monthly. Soon after appointment, the AC asked for more information, such as a medium-term burn forecast so that bank or other covenant issues would be identified timelier. Meanwhile, the PE firm invested further capital, squeezing down management owners.

Within a few months, in a board meeting, AC members stated their opinion that the firm would soon be, if not already, in extremis. Neither the firm's nor the PE's in house counsel weighed in on this concern as advisors to the board. The PE firm and management disagreed and proceeded to try and arrange an unsecured financing package.

Management began to adopt various cash preservation methods and sought other solutions such as a merger. Key decisions led by the PE were being rapidly made without full board knowledge or input. Over concern about their duties as directors and the lack of timely communication, the AC sought independent counsel. They then demanded to be kept abreast of key decisions. Now, almost a year later, the PE firm decided to restructure the board and discharged all the independent directors. After a failed restructuring attempt, the PE put the firm into Chapter 7. The management owners sued the PE firm (but not the former independent directors) over the loss of value and ultimately received a settlement.

Topic 3: Cash flows versus earnings valuations

Author: Dan Brill, MBA

Introduction

Senior executives and Board Members should examine, address, and focus on cash flow as well as earnings to get a better understanding of a firm’s risks, opportunities, and its ability to uncover hidden value by the use of two different criteria: cashflow and earnings.

Earnings based multiples are often used to get a rough estimate of a company’s value. Many, if not most, public company management teams and boards focus on earnings and appropriate earnings multiples to assess performance. A more accurate method is to discount the company’s future cashflows at a rate that reflects the risk of generating those cash flows relative to the lowest risk available, such as U.S. treasury bonds. If management takes more risks to generate the same cash, the firm’s value will fall. If US treasury bond rates decrease the firm’s value will increase.

Here is one example of the inability of the stock market analyst and investors to accurately assess the value of a publicly valued firm. The shareholders saw what was based on historical earnings, while cash flow investors saw what could be based solely on maximizing future cash flows.

Board members should require management to describe each segment’s total capital, its cash flows, and its earnings. The two separate perspectives may enable management to reduce risk and increase value.

Questor Inc.

In 1983, the share price of Questor, a publicly traded global conglomerate was under pressure due to back-to-back losses of US$25 million in the prior two years. At that time, Questor had four main divisions: Spalding sporting goods, Evenflo baby bottles, industrial ceiling fans, and juvenile products.

That same year, a group of four cash flow focused investors studied the company’s performance based on maximizing cash flow and concluded it could be run much more efficiently. They offered a premium to the share price and bought all the shares of Questor for US$115 million using a highly leveraged capital structure of US$15 million of equity and US$100 million of debt.

To create value, these cash flow focused owners reduced the firm’s global management team from one hundred and ten to seventeen, consolidated the ceiling fan production sites into one plant then sold it to management, focused on Spalding’s premier products and licensed the production of the rest to others, and sold juvenile products.

Their attention on building the high-value branded products, using funds generated by the sale or closure of low return businesses created a company that required much less capital investment to function successfully. In just over a year, they paid off half of the original US$100 million debt generated US$50 million in earnings.

The team’s ability to generate high value, predictable cash flows coupled with their ability to reduce the overall business risk was handsomely rewarded. In mid-1984, they sold their streamlined, extremely cashflow focused company to a private conglomerate for US$360 million, or approximately twenty times their initial equity investment.

The importance of cash flow

Too often the board and management are focused solely on GAAP profitability measures such as earnings, and revenues, in lieu of cash flows. The ultimate responsibility to manage the business risks associated with cash are no different than for all the other business risks for which the board has the risk management responsibly.

Cash is the “lifeblood of the company” in sustaining your business. Without adequate cash flow to support the business operations, the business will not be able to accomplish short and long-term objectives. Ultimately, inadequate cash resources could lead to an operational restructuring or the failure of the business.

Cash flows are also an important factor in determining the adequacy of market capital requirements, such as risk adjusted return on equity, and basic capital requirements, such as working capital. The Cash Flows: the Analytical Model (Figure 1) is an analytical model that aids in understanding and monitoring operational and capital cash flows.

HSG has previously authored articles related to cash flow in Business Law Today and The Corporate Board. Most recently, the ABA published an HSG-authored book Corporate Governance: Understanding the Board-Management Relationship, which focuses on the roles of the board, the CLO and CFO in monitoring cash flows.

Disclaimer: The information in any resource in this website should not be construed as legal advice or as a legal opinion on specific facts, and should not be considered representing the views of its authors, its sponsors, and/or ACC. These resources are not intended as a definitive statement on the subject addressed. Rather, they are intended to serve as a tool providing practical guidance and references for the busy in-house practitioner and other readers.