Banner artwork by rudall30 / Shutterstock.com

In-house lawyers are a bit of a secret weapon for companies, but not in the way you may be thinking.

Sure, we keep the wheels of commerce rolling smoothly, manage a slew of business risks, and are essential allies in a crisis. What HR teams and management secretly love, however, is how much in-house lawyers contribute to companies’ diversity efforts.

Where can we find a group that not only is majority-comprised of women, but has excellent management representation, even frequently in executive management? The legal team is exemplary at many companies.

Note, while this discussion cites data from the US legal market, I’ve observed similar trends in other markets, including in Europe and India.

The reasons for in-house legal teams’ outperformance no doubt include our genuine commitment to diversity. But we also benefit from two powerful environmental factors: ample supply and weak competition.

I’ll describe both factors, and why our very success is contributing to an ugly distortion in the broader legal community. I’ll end with a concrete recommendation about what in-house legal teams can do to help move towards balance.

Supply: A rich palette of talent to choose from

Law school is the ultimate egalitarian endeavor. At least as it concerns gender parity, women and men have been enrolling in law school in equal numbers for decades. In fact, women enrollees have outpaced men every year starting in 2016.

What this means is that when in-house legal teams need to hire new lawyers, we are spoiled for choice, certainly compared to many professions.

For reasons I’ll explain in a moment, an even greater proportion of female lawyers than law school graduates want to work in-house.

What’s going on, you wonder, and where’s the failure I’m hinting at?

Competition: Why is in-house practice desirable?

Before we congratulate ourselves on being so wonderful, consider that it might not be us so much as the wretched competition.

According to ABA statistics, more than half of law school graduates enter private practice upon leaving law school. Just about 10 percent start by working in-house. That certainly doesn’t look like in-house teams have any recruiting advantage.

But what happens each year after lawyers start to work? A certain percentage leave their law firms and look to move in-house. That reliable recurrence is what concerns us today.

But what happens each year after lawyers start to work? A certain percentage leave their law firms and look to move in-house.

The depressing truth: Law firms are failing on a grand scale

When I say law firms are failing, I mean they’re failing to create an environment in which women thrive and move into more senior roles.

Consider this:

- Women constitute not quite half (47 percent) of all associates at law firms.

- Women represent 32 percent of all non-equity partners.

- Just 22 percent of law firm equity partners are women.

From starting in the majority as junior associates, women steadily leave law firms at greater rates than men and are significantly underrepresented in management. Not only that, but male partners have substantially higher average compensation than women partners.

When I say law firms are failing, I mean they’re failing to create an environment in which women thrive and move into more senior roles.

If you ask them, everyone involved will tell you they’re unhappy about this. The women for certain, as we’ll see in a moment, but the men leading law firms as well.

In what ways do law firms underperform?

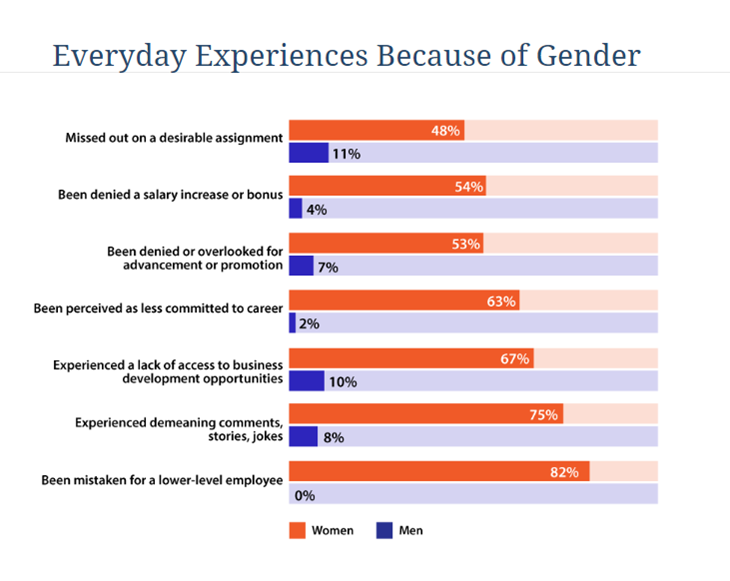

The results of detailed inquiries into the law firm experience are sobering (from the ABA Profile of the Legal Profession 2022):

According to the same ABA study, the three top reasons women say they leave law firms are because of caretaking commitments, stress at work, and the emphasis on marketing or originating business.

Well, there you have it. Suddenly it becomes clear why in-house practice looks so attractive. We offer flexibility and part-time work, we are careful to acknowledge and mitigate stressful conditions, and our lawyers have no pressure to originate business.

Can in-house lawyers help solve law firms’ problems?

Let’s assume law firms are making genuine efforts to stem the loss of so many talented women. Whatever they’re doing is not working.

No matter how good one’s intentions, perceptions form reality. The statistics about women’s daily experiences show what those perceptions are, and they’re not good.

A lot of well-meaning people have spent a lot of time both thinking about this and trying to improve. It would be arrogant of us to assume we know their motives or how to create better outcomes.

But we do know that incentives drive behavior. If today’s behaviors are not driving the desired outcomes, then the incentives are not sufficiently aligned. It is thus on the incentive side where we in-house counsel may play a constructive role.

Because I don’t think anyone has an easy fix, it’s likely counter-productive for us to try to mandate an outcome. Individually we don’t have the leverage and such requests are adjacent to our core work priorities.

Perhaps we can create greater incentives by reminding law firms this issue is important to us. How? Just ask them about it. That is much easier and relatively non-controversial.

If the majority of a firm’s clients are routinely asking about diversity, law firm management would have a new incentive to keep trying.

Perhaps we can create greater incentives by reminding law firms this issue is important to us. How? Just ask them about it. That is much easier and relatively non-controversial.

3 questions in-house teams could ask their outside counsel

How about once a year we simply ask our law firms these questions:

- What are the current diversity statistics for your firm as a whole? How do these compare to the prior two years?

- What are the diversity details of the lawyers currently working on our engagement?

- Please describe any commitment to improve your diversity performance you have made. How have your prior commitments been implemented?

Be careful what you wish for

Note that if we’re successful in moving the law firm needle, we’re going to make it harder to recruit lawyers to our in-house teams from private practice. Rather than having a job that sells itself because the competition is terrible, we’ll have to convince potential hires how wonderful we are.

I am confident we’re up to the challenge.

Be well.

Disclaimer: The information in any resource in this website should not be construed as legal advice or as a legal opinion on specific facts, and should not be considered representing the views of its authors, its sponsors, and/or ACC. These resources are not intended as a definitive statement on the subject addressed. Rather, they are intended to serve as a tool providing practical guidance and references for the busy in-house practitioner and other readers.