CHEAT SHEET

- Recognizing the gap. In 2017, women make up for 25 percent of the Fortune 500 general counsel, and 26.8 percent of S&P general counsel. However, minorities make up just 10 percent of general counsel in Fortune 500 companies and 11.62 percent in S&P companies.

- Reinforce the design. The deficiencies in retention and promotion may be attributed to the design of diversity initiatives. Diversity initiatives are insufficient if they do not also increase the meaningful participation at elite and leadership levels of the profession.

- Cultivating the future. The underrepresentation and the slow increase in racially diverse leadership can generate an adverse cyclical effect that slows future growth. Having a diverse leadership team can enhance networking, mentorship, and sponsorship opportunities for cultivating future talent.

- Future problems. While minorities constitute 27 percent of law school students, they make up for just 10 percent of general counsel in Fortune 500 companies. The slow speed of change poses a significant problem, as the demographics of corporate leadership don’t align with the corporation’s clientele.

There is little doubt that we are living in a dynamic world, and the legal field is not exempt to the evolving demands of the market. The shifts in demographics and the growing awareness of the benefits of diversity and inclusion have led to an increased endorsement of diversity initiatives at both firms and corporations. Over the past few years, these efforts have led to some successes, but the progress has not been uniform.

In comparing the data on general counsel from 2017 Fortune 500 and S&P 200 companies, we have seen some good news with the continued increase in gender diversity. However, there is a disparity in the growth rates of gender and racial diversity as the rate of increase in gender diversity vastly outpaces that in racial diversity. This article sheds light on the phenomenon, and presents the implications of the findings.

Gender diversity is improving among general counsel

With the changing demographics and growing business competition, there is a necessity in corporate America to embrace diversity and inclusion. Promoting a focus on diversity and a culture of inclusion is critical to a company’s overall performance. On the one hand, the strength of an organization rests fundamentally on its talent. In today’s business environment, an enterprise must diversify and enlarge its sourcing pool to attract the best talent. On the other hand, a company must be diverse if it is to reflect the demographics of its clientele, and fully align with the interests of its customers. Yet, simply promoting a diverse composition within the company would not be enough without also fostering an inclusive environment. The company and its leadership must listen to and provide value to the different perspectives that diverse employees bring to the table. Indeed, research has repeatedly shown that diverse input in teams leads to better decision-making, greater innovation, and increased financial returns. Finally, an inclusive culture increases employee satisfaction, which in turn generates a positive cycle of recruiting and retaining diverse talent.

In response to this business imperative, companies have announced and implemented various initiatives to increase diversity. Specifically, within the context of in-house law departments, general counsel are using both the carrot and the stick to promote diversity in the external law firms that they employ. For instance, Microsoft has created a bonus program rewarding external firms that meet certain diversity targets, and MassMutual has terminated the use of law firms that do not meet its diversity expectations.

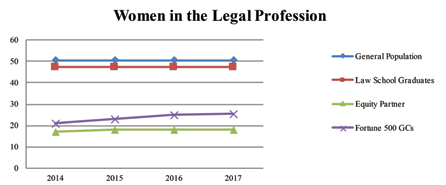

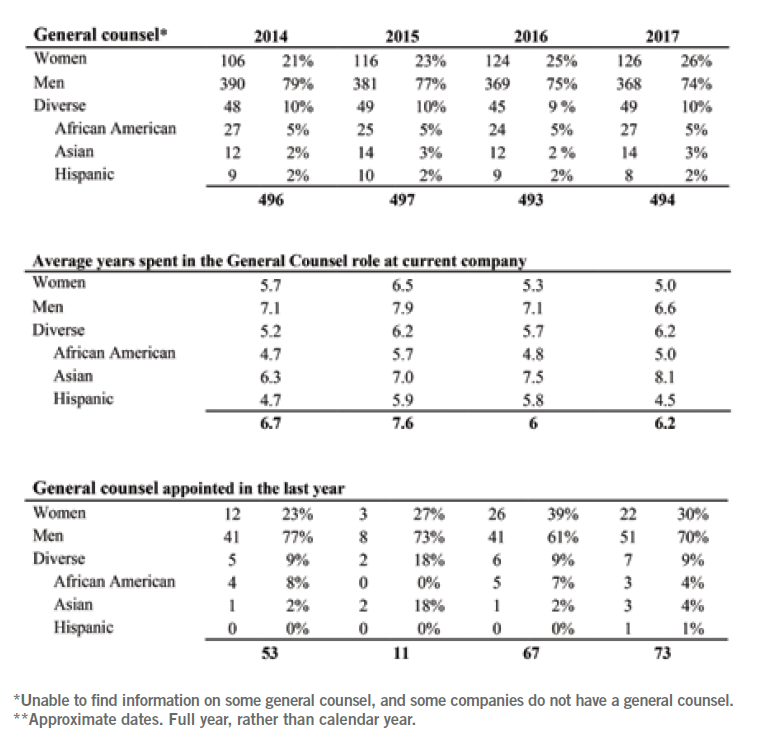

To date, the results within corporate America have been promising with regards to improvements in gender diversity. In 2017, the data shows an increase in the number of newly appointed female general counsel and a continuing upward trend in gender diversity within the Fortune 500 and S&P 200 companies. Women now make up 25.5 percent of Fortune 500 general counsel, and 26.8 percent of S&P general counsel. Moreover, 30.1 percent of the newly appointed Fortune 500 general counsel are women. Many articles have identified this phenomenon, whether as a sign of corporations’ taking strides toward diversity or as a chastisement to the slower progress of law firms. Writers have attributed this shift to hiring general counsel from in-house positions and not from private practice — from which there are a limited number of females in firm leadership. In addition, the shorter average tenure of GCs, compared to equity partnership provides more opportunities for women to be appointed.

Racial diversity is not sharing the gains made in gender diversity

However, the improvement in gender diversity is an incomplete picture at best. Similar increases been not been replicated in the diversity of minorities within the ranks of general counsel in Fortune 500 and S&P 200 companies. In total, minorities make up just 10 percent of general counsel in Fortune 500 companies and 11.62 percent in S&P companies. Whereas the growth rate for minority general counsel has vacillated between nine and 10 percent in Fortune 500 companies over the past two years, the percentage of diverse GCs has actually fallen by 2.95 percent from 14.57 percent in 2015 to 11.62 percent in 2017 within S&P companies. Female minority general counsel numbers are disheartening: white female general counsel in Fortune 500 companies outnumber minority female general counsel at a ratio of 5:1.

Various explanations are possible to account for the phenomenon

The deficiencies in retention and promotion may be partly attributed to the design of diversity initiatives. Many racial diversity initiatives focus on improving formal diversity — equality in the opportunity to participate, which is an important but insufficient part of the effort to increase racial diversity within the profession. Diversity initiatives are insufficient if they do not also increase the meaningful participation at elite and leadership levels of the profession: substantive diversity. This is frequently apparent in the billing information provided by external counsel. While corporations such as MassMutual track the diversity of external counsel employed to work on company matters, the amount of billings by diverse associates is not reflective of any real improvement in diversity at the leadership level, namely the top 10 percent of the highest compensated lawyers at the firms. Therefore, initiatives by in-house counsel to promote diversity in their external counsel should have more holistic criteria to assess the firms’ progress in diversity.

It is hoped that the general counsel initiative to implement ABA resolution 113 will at least put some transparency to the data relating to the true levels of different diversity and the various levels or responsibility within a law firm.

Diversity initiatives are insufficient if they do not also increase the meaningful participation at elite and leadership levels of the profession: substantive diversity.

On the other hand, the underrepresentation and slow rate of increase in racially diverse leadership can generate an adverse cyclical effect that slows future growth. Having a diverse leadership team can enhance networking, mentorship, and sponsorship opportunities for recruiting and cultivating diverse talent. Consequently, the underrepresentation at the leadership levels limits these opportunities. For example, one barrier that diverse lawyers report facing across the board is lack of access to informal networks. Especially in a service profession that emphasizes building relationships, the ability to develop formal and informal networks plays a significant role in an lawyer’s career advancement. Often, these networks are already established, and they may be even more difficult for racially diverse lawyers to enter and navigate. Furthermore, seeing the lack of diverse leaders and role models at the company can be discouraging to diverse lawyers who may perceive their possibility of promotion to be slim. Finally, unconscious bias or actual prejudice may have a disproportionate negative impact on racially diverse lawyers. Together, all these negative influences can themselves perpetuate a slow growth rate in hiring and retaining diverse talent.

Another explanation may be the changing approach of corporations with regard to diversity. From conversations with in-house counsel, it appears that some companies are increasingly redefining the parameters of diversity such that it extends beyond race to factor in socioeconomic backgrounds, education, sexual orientation, veterans, and other background experiences. According to in-house counsel, previous assessments of diversity were mainly limited to increasing the most visible measurements such as gender and race. The transition to a wider set of diversity standards may dilute the focus on racial diversity.

The widening gap will pose problems for the future

It is clear that companies voice strong messages about their commitment to diversity, but the lack of improvement in racial diversity will become increasingly problematic in the future. The rhetoric is a familiar one: the legal profession must increase its diversity initiatives to better serve the client, and stay competitive in the domestic and global market. The problem is less so at the production level of law school graduates and more geared toward the leadership composition. Indeed, as of 2017, there are now roughly 50 percent of women in law schools, and the number of female general counsel represents roughly half of the expected percentage. However, turning to racial diversity, while minorities constitute about 27 percent of students in law school, they make up just 10 percent of the general counsel in the Fortune 500 companies. That number is 37 percent of the expected percentage. Worse yet, this number has been stagnant for the past few years. Considering current minority groups will eventually become the majority at 56 percent by 2060, the slow speed of change poses a significant problem as the demographics of the corporate leadership grow more disparate from the composition of the corporations’ clientele.

Unless corporations begin replicating their successes in gender diversity initiatives in the scope of racial diversity, the problem will only become worse going forward. The solution will involve a reexamination of current diversity initiatives to assess their limitations, and begin applying a more holistic strategy to retain and promote diverse talent to leadership levels.

Further Reading

Eli Wald, “A Primer on Diversity, Discrimination, and Equality in the Legal Profession or Who is Responsible for Pursuing Diversity and Why,” 24 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 1079 (2011).

See, e.g., Vivian Hunt et al., Diversity Matters, McKinsey & Company 9 (2014).

Lydia Lum, “Women as General Counsel,” Diversity and the Bar, Nov./Dec., 2015, at 18–19.

Wald, supra note 1 at 1105–1106