A federal judge recently sentenced Michael Cohen, US President Donald Trump‘s former personal attorney, to three years in prison after he pleaded guilty to several crimes. The eight counts included allegations that he paid hush money to silence two women who allegedly had affairs with Trump, violating campaign finance laws. Cohen also pleaded guilty to lying to banks to obtain improper loans and lying to the government to avoid paying taxes.

Cohen claimed some of his crimes were committed at the direction of the president. For example, he claimed he paid off adult film actress Stormy Daniels at Trump’s direction to prevent her from speaking out about her affair and thus weakening Trump’s chance of winning the presidential election.

Cohen also stated that he performed “dirty deeds” on his client’s behalf, which Trump denies. In a tweet responding to his former boss, Cohen stated:

"Recently the President tweeted a statement calling me weak and it was correct but for a much different reason than he was implying. It was because time and time again I felt it was my duty to cover up his dirty deeds."

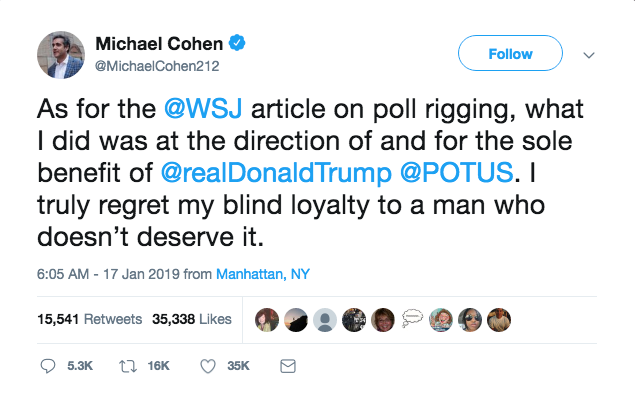

Since then, The Wall Street Journal reported that Cohen hired a technology firm to rig online polls on CNBC and the Drudge Report to increase Trump’s credibility as a presidential candidate. The Trump Organization declined to comment to their report.

Cohen responded to the story with this tweet:

In an interview, Rudolph Giuliani, Trump’s current lawyer, has denied Cohen’s claim and the president’s knowledge of the incident.

The takeaway

Regardless of your stance on the Cohen/Trump relationship, Cohen’s plight should serve as a cautionary tale to lawyers everywhere. It is especially relevant to in-house lawyers whose careers and daily work are often dependent on a single company with a sole group of business professionals.

General counsel typically report to one chief executive officer and don’t have the luxury of firing their clients when strategic or ethical differences of opinion arise. The CEO, who usually has no legal background or training, is often a business person focused on the bottom line. Sometimes the work required of the lawyer leads to clashes at the intersection of commercial ambition and ethical conduct.

As Michael Cohen’s situation demonstrates, there are real consequences to criminal and unethical behavior for lawyers. What can in-house counsel do when faced with direction from the business or from their client that contravenes the law or crosses ethical lines?

1. Decide who you are

As the year comes to an end, reflect on past personal performance and make decisions and adjustments for next year. Most lawyers do not wake up one morning and decide to embark on a life of crime. Sometimes the line is barely visible until it has already been crossed.

The first thing lawyers can do is decide who and how they will be from a moral perspective. Committing to integrity even when no one is watching makes it easier to avoid ethical breeches and criminal conduct.

The lawyers who take a wait-and-see approach, who make ethics decisions based on what they think they can get away with, are much more likely to end up facing ethical discipline or criminal penalty.

2. Be prepared to quit

I received this advice years ago from an associate general counsel who had resigned from his former GC role rather than commit the ethical breaches his CEO demanded. His personal “this is who I am” rectitude led him to take what seemed to be an extreme measure to maintain his integrity and high ethical values. After he resigned, his company and some former colleagues came under federal investigation. Here are other more high-profile examples:

- Sanford Wadler, former GC of Bio-Rad, won a whistleblower suit after he was fired for requesting an investigation into the company’s potential bribery activity in China.

- Former GC of Glock Inc., Paul Januzzo, was convicted of racketeering and gun theft before his conviction was ultimately overturned. He claimed Glock’s founder and two outside lawyers framed him after he learned of their illegal activities, and his wife (a Glock employee) shunned the founder’s advances.

- Along with the CEO, PetroTiger General Counsel Gregory Weisman pled guilty to conspiracy for paying bribes and collecting kickbacks in violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. He was disbarred in two states and suspended from securities practice.

While quitting sounds extreme and is certainly uncomfortable, it pales in comparison to being stripped of your license to practice law or going to prison.

3. Keep your eyes open

In many cases, the CEO doesn’t fly into your office and say, “The Feds are coming – start shredding documents!” In those situations, your response should be obvious and the choice absolutely clear.

But at other times, the worms of moral turpitude creep up on you, nibbling away at the edges of your moral foundation. What may begin as harmless white lies can turn into cover-ups for petty crimes. Over time, your ethics have crumbled.

This is avoidable. Just as you guide your CEO and colleagues to make the most ethical decisions, you should also hold yourself to the same rules.

4. Know your organization

Lawyers are well advised to be vigilant for the seemingly innocuous steps that could lead to professional peril. Understanding your company’s culture on ethics is the first step. The tone from the top is often the first big clue to what happens on the ground. For example, your risk in winding up in an ethical quandary is lower if your CEO:

- Insists on uncompromising integrity at all times;

- Advocates immediate investigation of all whistleblower and ethical complaints;

- Supports termination of employees for ethical violations at all levels of the organization, with no exceptions;

- Requires the installation of measures (e.g., transparent reporting to senior leadership of all ethics complaints, tracking resolution times, the appropriateness of remedial actions) and monitoring to mitigate ethical risk; and

- Advocates walking away from commercial opportunities that require bribes or other unethical conduct.

On the other hand, you should be wary, and ready to put your running shoes on if your CEO:

- Is sort of committed to ethical conduct depending on the situation;

- Only supports the termination of certain employees at certain levels who commit ethical breaches;

- Tolerates unethical or borderline criminal conduct from friends, high performers, or senior leaders; or

- Expects you to bend ethical rules as needed for the greater good of the organization.

5. Know the rules

You don’t have to be a criminal lawyer to know when you are crossing the line into criminal activity. The higher standard that has greater daily relevance for lawyers is complying with the rules of professional conduct which govern the practice of law. Every lawyer is expected to know and comply with all rules of ethical professional conduct as well as the law.

At my former employer, John Crane, our CEO adopted our company’s code of ethics from his military days and boiled it down to a single sentence that everyone in the organization memorized. It served us very well:

Don’t lie, don’t cheat, don’t steal, and don’t tolerate those who do.