It’s not uncommon for attorneys to be told, in admiring tones, by complete strangers that they wish they had attended law school. Our reply is often an exasperated: “Why?!” Followed by their proud retort: “So I can learn to think like an attorney!”

While the ability to “think like an attorney” may remain a desired trait for Perry Mason fans, in the corporate world we have discovered that some components of “attorney thinking” may hinder you from becoming an effective in-house counsel. In this article, we discuss how to break away from aspects of “thinking like a lawyer” and focus on solutions for your in-house clients.

Boil the tea pot, not the ocean

From the beginning of law school to your time shepardizing citations for a law journal, you have been taught to sweat every single detail of every single case and matter, because we must be zealous advocates for our clients and protect them from all risks, foreign and domestic. There are few other professions where one would be excited to spend an entire class focused on footnote 4, let alone on a matter decided in 1938!

Once you are in the corporate world, you may find occasional appreciation for your attention to detail, but just as often business clients will not deign to delve into your brilliant analysis about whether your next master services agreement should begin with “thee” or “the.” Instead, clients may just read the skip to the end of the memo. In the meantime, sweating every detail for one client has created a massive logjam of other frustrated internal clients.

The solution? Stop “thinking like a lawyer,” where every last detail is of equally mammoth importance. Your company has priorities: Not all requests made to legal are of equal significance. And your client may be happier to receive a faster answer from you, rather than waiting for you to explore every potential rabbit hole.

Breaking records

Much of a lawyer’s training is built around litigation. We study opinions by leading jurists and parse arguments by skilled advocates. We trace disputes up to the appellate level, where courts create new precedents.

As we talk in class about poor Ms. Palsgraf, we learn about potential shortcomings in how her case was adjudicated, such as, ”Why didn’t they call more witnesses to testify?” We vow to never make such factual oversights ourselves when preparing a case. We start “thinking like a lawyer…”

A lesson we take from law school, as well as the court system, is that we always need to build a record of every fact and possible argument to preserve it for appeal.

While that approach may be perfectly suited for litigation, it is rarely appropriate in the corporate settings, where decisionmakers don’t care whether certain arguments were made or facts were known in the past.

Corporate decisionmakers care about making the right decision at that moment, even if some of the facts at hand were just uncovered.

Corporate decisionmakers care about making the right decision at that moment, even if some of the facts at hand were just uncovered.

Stop “thinking like a lawyer” and building that voluminous record for appeal of every prior discussion. No one in the corporate setting cares whether a particular argument was made before. Treat every decision as a de novo matter, regardless of its history.

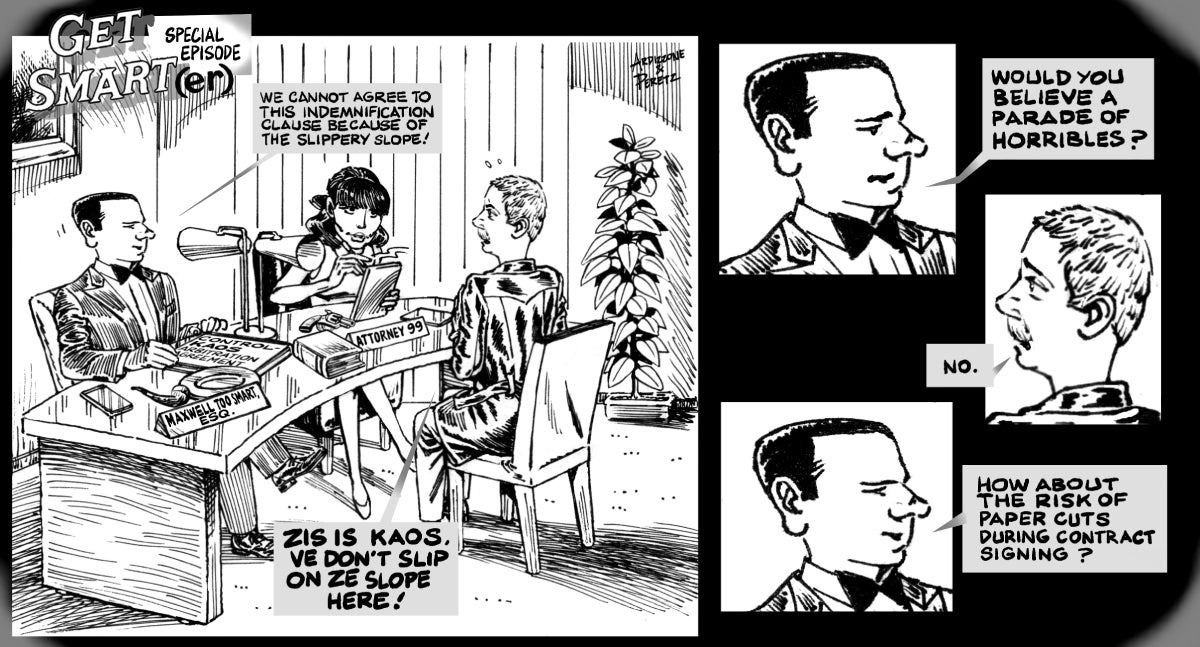

Business hypochondria

Lawyers are great at identifying potential risks, regardless of how unlikely they are to occur. For many, “thinking like a lawyer” turns every task into a golden opportunity to identify risks that even a hungry insurance salesman might overlook. The result is that your clients often shut you out of all discussions, because you are unable to see that business often requires some degree of risk-taking.

It’s time to stop “thinking like a lawyer” and start thinking like a bookie making odds. Bookies are the antithesis of “thinking like a lawyer”: They know that not every risk is equally likely and they survey the market and experts to weigh and communicate the odds.

Stories beat rules

Some lawyers are a fount of legal knowledge, reciting lengthy statutes from memory. While they may win the “looking like thinking like a lawyer” award at the talent show, they often fail horribly in key negotiations. The reason for their failure: spitting out laws has far less impact than spinning out yarns. Stories beat rules in almost every real world setting outside of the courtroom.

The next time your client is negotiating a key deal term, provide hypothetical examples of how particular proposals and options may play out. Exemplary scenarios are far more persuasive than arguments based on precedents and statutory citations. It’s true that your client and the counterparty will give you less points for sounding like a lawyer when you provide these examples; however, you can take great solace in getting the deal done!

History dominates law school

Law school can be thought of as a three-year foray into the history of the legal system. There is a strong emphasis on how different areas of law came to be, how they evolved over time, and how they play out in the courtroom today. You enter law school with little to no understanding of how the legal system works and how laws are actually developed and become binding. Accordingly, law school has long focused on filling that gap.

Learn about the ACC CLO Club, a global network for the highest-ranking legal officer.

Your first year of law school at nearly all law schools consists of the same set of courses. You are taught how these areas of law came into existence. You are taught how the laws in each area of law were developed and the core court cases that underlie these laws. Given the lack of knowledge of most incoming students, law schools are not misguided in focusing on these foundational courses at the beginning of the law school curriculum. The side effect is that law students believe that “thinking like a lawyer” revolves around the study of legal history and evolution.

After the first year of law school, law students are often provided with a vast array of courses to choose from. Yet, most of these classes continue that first-year norm — a focus on legal history and not on practice. This can create law students who graduate with scant practical experience beyond that gleaned from a brief internship, externship, or clinic from their 2nd and 3rd years of law school.

All too often, their first real practical training comes post-law school, working at a firm where training is focused solely on the limited scope of the firm’s specific practices, rather than the bigger picture of how lawyer’s historical thinking and research don’t scale well when present day matters demand their attention.

Lawyers do not know it all

Lawyers often come across as the classic “know-it-all.” There is a reason for this. Part of thinking like a lawyer is a self-belief that you, the lawyer, are the sole source of advice and reasoning when it comes to legal matters. In law school, so-called “gunners” epitomize this mentality as they frequently broadcast their perceived legal expertise unsolicited, even when it is time for a different perspective.

While being a know-it-all may earn you praise from your law school professors who are glad when anyone is willing to volunteer an answer to the 33rd Socratic question of the day, these tendencies often do not fare well in the real world. Questions that you deem to be “legal” often have many other dimensions and require input from perspectives you lack, ranging from finance to marketing to staff morale.

There are numerous business implications for almost every legal decision made. You may know a lot about a certain area of law, but the business doesn’t care about your legal expertise in isolation. The business wants to know the knock-on effects of deciding to go in one direction over another. When you are acting like a Know-it-All, your clients are rolling their eyes about all the non-legal blind spots in your analysis.

To become successful in in-house practice, you need to overcome your “thinking like a lawyer” to learn “thinking like a CFO, marketer, HR expert, and publicist.” Sometimes knowing what you are missing is far more important than knowing it all.

Slow and steady may not win the race

Businesses move fast. They have to. To succeed as a business, the venture needs to be focused on growth. This means that decisions need to be made quickly and definitively. Law school teaches you to think through every possible consequence, every possible situation, every possible chain of events.

Business people are also busy-ness people. They want answers quickly.

This is fine when you are writing a law school exam essay. This is not fine when a business is depending on you to provide some guidance about a potential move or business opportunity.

Your business colleagues do not need you to restate all the facts in evidence, accompanied by supporting footnotes and appendices.

They want actionable advice that is increasingly driven by data instead of legal intuition. And they cannot tolerate weeks before you analyze all possible hypothetical scenarios.

This can be challenging for lawyers who are taught to think through everything and analyze every possible risk, then present that comprehensive analysis in a memo to a client. Business people are also busy-ness people. They want answers quickly. Your “thinking like a lawyer” may make you slow and deliberate. The result is that you may be bypassed entirely, as the deal is done before you author page 18 of your next memorandum.

Think like a winner

Lawyers tend to think that winning means you win and someone else loses. This may be true in the courtroom in many cases, but in the business world, winning is not so black and white. Starting in law school, law students and the lawyers that they become are inherently competitive, so winning takes on a certain importance and value. After all, only so many snag those coveted summer associate jobs with multinational law firms and prestigious judicial clerkships.

Outside of the courtroom, winning can take the form of closing a deal with a major customer, starting a new partnership with a company, or even working on a joint project with a competitor. Such activities may not, at first glance, feel like “winning,” but winning in business is a long-term game.

Thinking like a lawyer just focuses you on the case at hand, with the consequences be damned for future matters. While the business world appreciates short-term wins, it is often the long-term wins that make the most difference. This means in-house lawyers need to develop skills that are rarely attributed to lawyers: being collaborative, fostering relationships, and building trust with other parts of the business.

You better think (think)

Perhaps the best advice about thinking like a lawyer comes from the mighty Aretha Franklin, who observed that “People [are] walking around every day, Playing games, taking scores.” Don’t get caught up in others stereotyping of what it means to “think like a lawyer.” It’s time to “Let your mind go, let yourself be free. Oh, freedom (freedom), freedom (freedom)!!”