Picture yourself in this scene. You are supporting a nighttime clandestine operation, underwater, and wearing scuba gear. The sea is pitch black, and you are hanging onto the deck of a submarine that’s propelling through the ocean away from the target area. Your nerves and muscles are tense because you know how vulnerable the US$1 billion submarine has become while you “de-rig” from the insert. Suddenly, your facemask and regulator are ripped off your face. You can’t see. You don’t have air. What do you do?

Tim Phillips can tell you. He’s been there.

Phillips serves as the chief legal and risk officer (CLRO) of the American Cancer Society and general counsel for its advocacy affiliate, the American Cancer Society Action Network. He serves as assistant secretary for both organizations. In his role as CLRO, he leads a team of legal and compliance professionals in their efforts to assure the society complies with the laws governing the modern charitable enterprise and is positioned to take full advantage of strategic opportunities to advance its life-saving mission.

Before he was saving lives with the American Cancer Society, he was doing it with another well-known organization: the US Navy SEALs.

I’ve worked with Phillips for many years on the ACC Law Department Management Network leadership, where he is currently chair. It recently occurred to me that the in-house legal community would benefit from the leadership lessons Phillips has gleaned from his years serving as — and training to become — a Navy SEAL.

An image inspires a goal

Phillip’s story began with a cover of a Parade magazine in the early 1980s. It showed an image of the now legendary BUD/S training: a group of wet, granite-faced men in olive drab uniforms, covered in sand and grit. The headline asked a pointed question: “Are These the Toughest Men Alive?” Although he wasn’t yet old enough to drive, an ambition became fixed in his mind: He would become a Navy SEAL.

A year of training — and the Bell

After graduating from the US Naval Academy, Phillips began his months-long journey of SEAL training. It began with an introduction that was scheduled to last for six weeks. When he arrived, however, he was ahead of his slated class. There was no “holding area” for the soon-to-be-in-a-training-class, so he “classed up” with the group one class ahead. Six weeks later, an officer informed him that since he had officially been assigned to the other class, and he’d have to do his training all over again. His six weeks became 12.

The next step was BUD/S, the Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training, which spanned 24 weeks in three phases. The first phase focused on physical and mental conditioning. In the second and third phases, Phillip’s class explored land and sea warfare, with demolitions, live fire training, and a grueling combat swimmer course, complete with pool competency and open water diving evolutions, that remain the core curriculum for any Navy SEAL.

[Related: Becoming a Honey Badger: Navy JAG Claire Huffstetler’s Path to Leadership]

Two of the most famous aspects of BUD/S are the "Bell” and “Hell Week.” The Bell refers to a ship’s brass bell that looms over the training ground. SEAL training is intended to test mental and physical limits, and fewer than 20 percent complete it. When exhausted SEAL candidates reach their breaking point, they drag themselves to the Bell and ring it three times. The sound echoes through the training grounds, announcing another candidate has “volunteered out.”

Hell Week is a part of the initial phase. Over five days, Phillips logged about four hours of sleep, ran over 200 miles, and trained for over 20 hours a day. During Phillips’ Hell Week, the Bell rang frequently. One part of Hell Week was similar to the land warfare phase but with one key difference: The ammunition and explosives in land warfare were live.

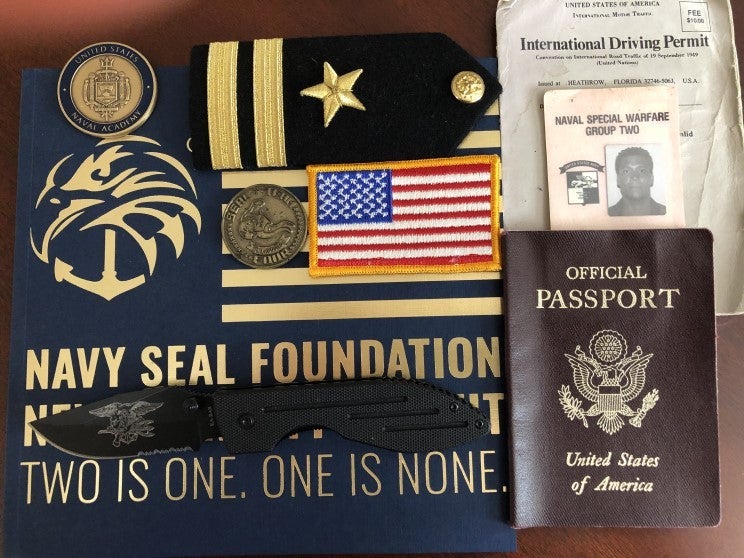

At the conclusion of BUD/S, Phillips’ SEAL training had reached the half-way point. He expected six more months of SEAL Qualification Training (SQT) to expand his tactical training about weapons, close-quarter combat, navigation, and demolition skills. But midway through his SQT, Iraqi tanks rolled into Kuwait, and the first Gulf War began. Phillips shipped out to the Middle East, and on his way, he received his Trident, the symbol that he had become a SEAL. He had reached the goal he set as a teenager, when he first saw his future teammates on the cover of Parade.

5 leadership lessons

During his SEAL experience, Phillips gained unique insights into leadership that all of us can use in our day-to-day roles as law department leaders. Here are five prime examples.

Lesson 1: Don’t ring the Bell

Most SEAL candidates don’t complete BUD/S. Instead, they walk up to the Bell and ring it three times. Phillips didn’t. Why didn’t he?

I believe that his perseverance was due, in large part, to his mindset. He was single-minded about his goal, prepared thoroughly, sought out opportunities to hone his skills early, and in each step he went above and beyond. For example, he completed Army Airborne School and Navy Scuba School before graduating from the Naval Academy. Neither was required, but by taking them, he gained strength and confidence. Another ingredient of Phillips’ attitude is called “flexible optimism,” a combination of a realistic assessment of where you are, and a firmly held belief that you’ll reach your goal.

Lawyers struggle with grit and perseverance. We tend to be a negative lot, seeing and expecting the worst. It’s an occupational hazard to some extent. For example, in-house lawyers who focus on transactions must anticipate events that create downside risk, and as a result, they must spend time envisioning and addressing problematic scenarios. The circumstances we consistently encounter in our jobs, whether because of time pressure or the importance of our tasks (or both), only add to the stress.

Flexible optimism can guide us through difficult scenarios. We can also combine flexible optimism with mindfulness, the concept of being fully present, using our abilities to their fullest. Interestingly, in his post-SEAL life, Phillips has become committed to yoga and meditation, making mindfulness practice a regular part of his life.

Lesson 2: The importance of the team

SEALs aren’t a group of solo artists doing Lone Ranger acts. They continually emphasize the importance of their team. SEAL missions are carefully planned, and each member of the team knows his responsibilities, and team members count on each other. If one link of the chain breaks, the consequences can be tragic. SEAL team members also provide key support at critical, and sometimes unexpected junctures. When Phillips lost his regulator and mask on an underwater operation, his dive buddy swiftly came to his aid, immediately knowing that he would share his regulator until Phillips’ safety was assured.

Although the stakes for in-house legal teams aren’t this fraught with danger, the role of team members is still fundamentally important. In interacting with our teams, we must deploy our emotional and business intelligence every day. Do our members know their roles? Are they appropriately cross-trained? Are our team members getting enough information about the business and industry to do their jobs and to anticipate potential problems? Do they have our support to grow and develop as professionals? Do they know that we respect, value, and celebrate them, both as team members and as people?

These are some of the many questions we must address as law department leaders. Without such key elements in place, law departments can become dysfunctional groups, where team members are working at cross-purposes, engaging in unnecessary turf battles, or simply failing to be effective.

Lesson 3: Leadership requires a healthy dose of humility

Phillips had a harder time learning this lesson. In his own words, his path to becoming a SEAL was fired by “adolescence and ego,” qualities not typically synonymous with humility. There are some hilarious examples of his learning curve. He showed up at a Naval Academy interview sporting a Mohawk. When he arrived at Scuba School, he proudly admitted to the Master Chief in charge of training that he was going to be a SEAL. The Master Chief, in a sarcastic tone, proclaimed to the rest of the class that they’d been joined by a “Jedi,” and the nickname stuck. When Phillips arrived at BUD/S in full uniform, displaying his Airborne wings and his Scuba School “bubble,” he was promptly dispatched to the ocean – wings and bubble attached.

As leaders of law departments, it’s easy to succumb to the temptation to dominate every meeting to show we’re firmly in charge and that we’ve mastered our organization’s legal issues. But if we suck all the oxygen out of the room, there is no place left for discussion, and we send the message that our team members’ ideas don’t matter.

Instead, we must create “psychological safety” in our teams. In other words, our law departments must be places where brainstorming is welcome; out-of-the-box thoughts aren’t treated with derision; and team members can shine and grow.

Lesson 4: Fail to plan and you plan to fail

The SEALs have a saying: “Two is one. One is none.” For example, does a SEAL have two dive masks or one? If something goes wrong with the first mask, he needs something to fall back on. If he doesn’t plan for the unexpected, his one mask can quickly become none.

One of our roles as law department leaders is to guide our organizations and our teams. We must think not only about what is needed to get the job done today but anticipate and prepare for what is on the horizon. For example, for many of us, cybersecurity is one of these matters. Have we evaluated and tested our defenses against cyberattack? Since cyberattacks are no longer the stuff of fiction, what is our plan for when a breach occurs? Are we sufficiently insured?

We are all familiar with such questions, but if we haven’t prepared for these issues ahead of time, our organizations can be left exposed. Contingency planning must be part of our mindset. Without it, we’re failing to plan, and therefore planning to fail.

Lesson 5: Taking the hard path

When faced with a choice, often there are two alternatives: one easy and the other hard. The hard one is usually the right one. That knowledge is one of the building blocks of integrity.

Phillips faced such a challenge during a SEAL training exercise. He was in command of a team that had executed a complex maneuver involving live explosives. During a gear check when the exercise was over, one of his team members found he was one grenade short. Although disclosing this aspect of his team’s performance involved a degree of embarrassment, Phillips dutifully reported it. Explosive ordnance disposal technicians later found the grenade on the training ground. If the lost grenade hadn’t been disclosed, serious repercussions could have resulted.

[Related: The “King” of Law Department Management]

Similarly, law department leaders must sometimes deliver unpleasant news or unwelcome messages or take steps to protect the integrity of the organization. It just comes with the territory. As the ACC’s report on the 21st Century General Counsel makes clear, a key role of general counsel is to serve as trusted counselors and advisers. When we’re presented with such a dilemma, do we take the hard or easy choice? We must step up to the plate and do what needs to be done.

Closing thoughts

As I reflect on my conversations with Phillips, there is a common theme. It wasn’t one we talked about, but it was there the whole time. It’s the concept of servant leaders, the leaders who focus less on themselves and more on the people and organizations they serve.

This is the thread that runs through his career: being of service, often to groups with big missions. We now know about his life as a SEAL. But in Phillips’s post-SEAL life, he has devoted his time and skills to organizations like the American Cancer Society and ACC, groups that are focused on giving back and providing resources for others.

I thank Tim Phillips for his service and for highlighting a philosophy worth putting into practice every day — and for not ringing the Bell!