CHEAT SHEET

- Ditch the lip service. Saying all the right things is a step in the right direction, but committed diversity programs require action.

- Cultivate relationships. Sponsoring diverse bar associations and working with firms committed to diversity are reciprocal relationships that will serve you well.

- Be aware of your influence. CLOs wield a tremendous amount of power in selecting which outside counsel to work with; working with minority-run firms helps establish them in the mainstream.

- Keep fighting. We’ve come a long way to achieving true inclusion in law — but we’re not there quite yet.

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.

Jackie Robinson is remembered because he was the first African American to play in the major leagues. He broke the color line in 1947 as part of success in a broader movement to end various forms of inequity and iniquity, including segregation, housing discrimination and lynching. Robinson did not consider his successful career with the Dodgers alone, as a triumph or victory for the entire sport. No team offered him a position as manager or executive when he retired. He refused an invitation to participate in the 1969 Old Timers game because he did not yet see “genuine interest in breaking the barriers that denied access to managerial and front office positions.” There wasn’t a black professional baseball manager until 1975. Jackie Robinson understood something fundamental about diversity: The integration of baseball provides a great example of how any effort at changing the dynamics of an institution must also involve a shift in power structures.

Minorities continue to be woefully underrepresented in major US law firms, particularly at the equity partner level. Considering the pivotal role that laws have played in making the United States a more integrated country (the Civil Rights Act of 1964, for example), it seems unfathomable that the legal profession would be in such a crisis when it comes to fully embracing minority lawyers, and minimally reflecting the population in terms of race, gender and all other categories. But this is the state we are in, and it needs to be addressed immediately.

For years, legal departments and law firms trumpeted a variety of pledges to hire more women and minorities to legal department and law firm ranks. Innovative in 1999, when Charles Morgan, then general counsel of BellSouth, first issued the Statement of Principle, such appeals seem outdated and hollow 16 years later. The “Call to Action” that followed was more forceful in that the hundreds of general counsel who signed it pledged to “end” or “limit” their retention of law firms that remained non-diverse. So, for a while, law firms scurried to launch diversity programs and hire diversity officers and the numbers were marketed as “improved.” However, it was all window dressing as institutions did not really change and power was not shared. This quickly became a case of “shout the ideas” but whisper the details and results as part of the marketing of diversity in our profession. And, general counsel paid lip service and did not always follow through on pledges to actually move the work. In fact, what’s happened since, not unlike major league baseball, has been alarming: Black lawyers are dwindling and are currently at a low not seen since 2000. If you look at major league baseball today, there are few blacks in the sport — as players or managers. According to a 2014 NY Times article quoting Major League Baseball numbers, only 8.3 percent of players identified themselves as African American or black.

The same article calls attention to the fact that, like within the legal profession, diversity initiatives are underway, quoting a black leader in the league, Jerry Manuel, former manager of the Mets and the Chicago White socks: “You want to give as many quality athletes the opportunity to choose to participate in the sport and eliminate as many barriers as you can.”

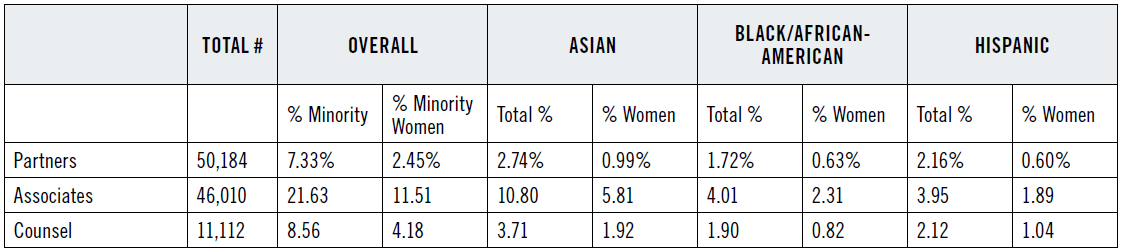

The latest statistics from The National Association for Legal Placement (NALP) reveal that minorities make up 25 percent of law school graduates and 21.6 percent of associates, yet only 5.6 percent are equity partners. It’s also important to note that while women have made the most progress, nonwhite women have not.

The pool of talent exists. In order to attract a diverse group of talent a wide net needs to be cast. Your fiscal health could depend on it — research shows that diverse corporations perform better — as well as your success in litigation. Decisions are made by a diverse group of people, from judges (in 2009, 29.2 percent of state court judges were women) to juries, and the lawyers working on the cases should reflect that. These numbers make the imperative clear. At this point, chief legal officers/general counsel, as corporate leaders, must look internally at our own initiatives before we expect sustainable results from outside counsel.

Diversity currency: Lip service is outdated

CLOs have a role to play in making diversity a priority and sustainable. Too often the conversation about diversity has taken a “do as I say” tone as those responsible for hiring outside legal teams have mandated diversity requirements, while not always holding their internal group to the same standards. This occurs largely by passing the hiring of outside counsel decisions on to subordinates who don’t get it, or shielding themselves through a convergence strategy that eliminates minorities from playing. To revisit the Jackie Robinson example, when he broke the color barrier it arguably ushered in the decline and subsequent elimination of the Negro league — a once thriving enterprise. Those players no longer had a league of their own to play in, and few opportunities (if any) to follow Robinson into the major leagues. Minority lawyers can often face similar odds. However, there are some GCs who are getting it right.

Ricardo Anzaldua, executive vice president and general counsel at MetLife, is one example of an executive who is making strides. In an interview with Bloomberg BNA, Anzaldua shared his thoughts on how to address the challenges with diversity that many organizations face. Although diverse attorneys may be recruited in representative numbers, the makeup of senior leadership is still predominantly white males. At MetLife, senior members of the legal department are held accountable for making sure that minorities are given the same opportunities for promotion. This type of sponsorship system ensures that individuals have a clear path to career success — and access to the resources needed to facilitate actualizing it.

Beyond making legal departments more diverse in numbers, there are a few strategies that CLOs can implement in order to demonstrate a commitment to diversity. Valuing a culture of inclusivity involves making choices about how time and money is spent. Sponsoring diverse bar associations like the National Bar Association (NBA), Hispanic National Bar Association (HNBA), National Asian Pacific Bar Association (NAPABA), National Native American Bar Association (NNABA) or National LGBT Bar Association, sends a clear message to their subordinates and outside law firms, as these organizations are committed to increasing both the visibility and permanence of minority lawyers in the legal profession. Additionally, attending diverse bar association events and conferences allows for collaboration between your internal team and members of these associations. This type of networking can serve as a first step in establishing relationships with lawyers who have the skill, background and expertise to handle your internal matters, even “bet the company” matters. Not showing up should no longer be an option.

Another approach to demonstrating a commitment to diversity is to find minority attorneys to work with as outside counsel. The traditional top-down law firm structure often means that partners have the most visibility and receive credit for the contributions of associates. Building client relationships is key to the business and professional development of associates as well as partners, and is often cited as a deficit in minority lawyers. A study by Nextions concludes that unconscious bias operates in the perceptions of a lawyer’s ability. A group of 60 partners were asked to evaluate a legal memo. When they thought the lawyer was white they praised him for having strong analytical skills; however, this same memo was given much harsher criticism and a lower overall score when they believed an African American wrote it. Minority lawyers are often evaluated more negatively than their counterparts due to what could be attributed to an unconscious expectation of subpar performance. This type of bias can also stand as a barrier to developing client relationships. For all those who let unconscious bias prevent them from working with diverse attorneys, there have to be enough of us who decide to do something different.

Retaining minority and women-owned firms is another way to increase diversity. According to “The Business Case for Diversity: Reality or Wishful Thinking?” a 2011 report by the Institute for Inclusion in the Legal Profession (IILP), small law firms owned by minorities and women did not compete for business from large corporations prior to 1988 when Harry J. Pearce, then general counsel of General Motors, stated that he wanted more minorities and women to handle GM’s legal matters. This public commitment to diversity by a major corporation precipitated a rise in small firms handling legal matters for corporations. IILP research shows that an increase in the use of diverse attorneys often coincides with such a pledge or call to action. Corporations who made a commitment to diversity increased their use of women-owned firms from 18.2 percent to 59.1 percent, as well as minority-owned firms from 29 percent to 67.1 percent. The National Association of Minority & Woman Owned Law Firms (NAMWOLF) is also an excellent resource; it helps to develop alliances between members, which are AV-rated firms from across the nation, and interested corporate legal departments.

The diversity litmus test

There is a range of questions you should ask potential firms in regards to diversity. Principally, you should find out the makeup of equity partners and their percentage of annual billings by diversity category. The ACC Docket article “Fixing What’s Broken: Strategies for Increasing Diversity in Law Firms” offers a great list of potential questions. Some key questions include:

- Does your firm have a succession plan? How many women and people of color are included in that plan?

- What is being done to ensure diverse associates are being given prominent roles?

- Which lawyers are recognized within the firm for significant results achieved for your company?

- What is the diversity of this group?

There are reasons why firms that set out with a great diversity recruitment and retention program sometimes fail over time. Make sure to look for those signs. A lot of the research suggests that the difference between a successful diversity recruitment program and an unsuccessful one is culture. An inclusive culture is necessary to retain minority lawyers. Look for firms that have a foundation of cultural competence and understand that inclusivity is an ongoing practice. The business case for diversity must be communicated to staff and reinforced by cultural awareness training so that everyone understands not only why diversity initiatives are important, but also how individuals are instrumental in creating an inclusive environment.

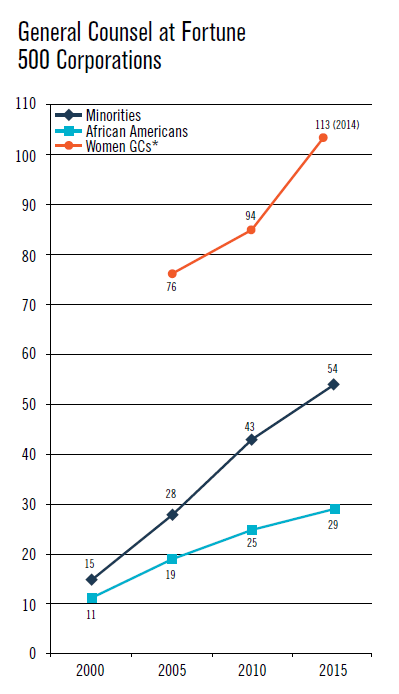

Per Women GCs: MCCA did not track women GCs separately from minority GCs in 2000, and as of date of publication, numbers for 2015 were not available.

Are we hypocrites?

Morgan’s “Diversity In The Workplace — A Statement of Principle,” which was followed by the “Call to Action” and authored in 2004 by former ACC board member Rick Palmore, then general counsel of Sara Lee — pledges to end relationships with firms that make no efforts to become more diverse. Several hundred GCs signed both documents. Other corporate general counsel and in-house counsel have made less formal commitments. Still, the 2011 IILP Report reveals that only 12.5 percent of corporations actually changed their relationship with law firms based on poor performance against their company’s diversity metrics or objectives. We can no longer afford to pay this type of lip service to diversity or the pledges that we sign.

Furthermore, if we expect firms to take diversity seriously then we as general counsel and chief legal officers must take it more seriously ourselves, both visibly and with our presence. It is quite telling that there are very few meaningful metrics that paint a picture of what corporate legal departments look like. At best we know who sits in the leadership positions.

We cannot begin to chart a course toward more representation of the population if we do not know where we are standing in corporate legal departments. “A call for results” is different than a call for action. As stated previously, the echelons of power must not only embrace diversity, but also reflect it in their own ranks. Celebrating, marketing and awarding “best practices” must give way to sustained best principles.

As a reminder of the legacy we have inherited and an imperative that reverberates beyond our professional circle, I borrowed the title of this article from a song penned by poet and activist James Weldon Johnson. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was first performed on February 12, 1900, in Jacksonville, Florida, by a group of black school children. The event, which took place at the school where Johnson served as principal, was meant to celebrate President Abraham Lincoln’s birthday and recognize his legacy — leading the Union to victory over the Confederacy, which led to the eradication of slavery in the United States. The song is a steady march. It’s aspirational in its tone and urgent in its delivery. For those 500 school children who first offered it to the world as their battle cry, it would be another 64 years before they would be recognized as full and equal citizens by the law. Having just passed the 50th anniversary of The Civil Rights Act, it’s fitting that as we laud our progress, we also do an internal review: What do we have to show for all of the struggles that came before this moment?

Further Reading

Dreier, Peter. “The Real Story of Baseball’s Integration That You Won’t See in 42.” The Atlantic: Apr 11, 2013.

Reddick, Malia, et al. “Racial and Gender Diversity on State Courts.” The Judges’ Journal. Volume 48, Number 3: Summer 2009.

Gore, Khurram Nasir. “Growing Diversity: Bridging the Gap Between Opportunity and Success.” ACC In-house Access blog: July 9, 2015.

Reeves, Arin. “Written in Black & White: Exploring Confirmation Bias in Racialized Perceptions of Writing Skills.” Yellow Paper Series: 2014.

“The Business Case for Diversity: Reality or Wishful Thinking?: The Institute for Inclusion in the Legal Profession and the Association of Legal Administrators. 2011.

Roellig, Mark, DeGraffenreidt Jr, James H. and Minehan, Cathy E. “Fixing What’s Broken: Strategies for Increasing Diversity in Law Firms.” ACC Docket, Volume 33, Number 2: 69-75.

Bentsi-Enchill, Jatrine. “7 Reasons Why Law Firm Diversity Initiatives Fail.”