CHEAT SHEET

- Ready, set, innovate. Innovation begins by identifying the problem and looking for creative ways to develop a standard solution.

- In the lead. Lead users are a class of end user who are the source of most innovation. In-house legal departments are potential lead users for the legal industry.

- Dashboards. At Siemens Canada, individual dashboard management systems are classified into one of three categories: strategic, operational, or transactional.

- Third parties. When automating key processes, consider engaging other parties such as partner law firms, legal technology providers, and internal software development groups.

The Siemens Canada legal department has had a long tradition of taking a business-focused approach to the in-house practice of law.

Our philosophy has two parts:

- Behave like owners of the businesses we work with; and,

- Run our legal department like a business.

It was the second leg of this statement that drove many of our early efforts to build processes and tools to help us manage both our operations and the transactions we support. A prime example is the dashboard management system that the department has now been using for several years. In this system, individual dashboards are classified in one of three categories:

- Strategic — encompassing performance in the most important matters or risks facing the business.

- Operational — the development and implementation of departmental or business processes.

- Transactional — the metrics of day-to-day performance (including both internal and external spending and litigation statistics and outcomes)

With respect to external-facing activities, our department developed a number of processes to streamline our commercial law systems — for example, processes that enable the efficient handling of low and medium-value contracts.

So, when the Siemens global legal department launched its Innovation Challenge, we treated our participation in it as just another business objective. We were soon to realize, however, that innovation was playing a key role in both parts of our philosophy and had the promise to be even more integral.

Figure 1: Profile of Siemens and its legal department

Siemens AG is a 170-year-old global company focusing on the areas of electrification, automation, and digitalization. It is a leading supplier of power generation and power transmission systems and a pioneer in infrastructure solutions, as well as automation, drive, and software solutions for industry. Its publicly listed subsidiary Siemens Healthineers AG is a leading provider of medical imaging equipment, laboratory diagnostics, and clinical IT. In fiscal year 2017, Siemens had revenue of CA$83 billion and over 370,000 employees worldwide.

Siemens Canada includes all of Siemens’ major businesses. In fiscal 2017 its revenues were CA$2.5 billion. The company has approximately 4,300 employees and 52 locations across Canada.

The Siemens global legal function is comprised of more than 60 legal departments. These include global groups dedicated to legal functional areas such as M&A, finance, antitrust, and technology, as well as regional legal departments that look after all of the corporation’s legal needs in a country or region.

The Siemens Canada legal department is a mid-sized group with substantial resources in the commercial and corporate law areas. Its members participate actively in Siemens’ global legal practice groups, notably those focusing on M&A, technology, and litigation. It also has a small but sophisticated legal operations group that works closely with its counterparts throughout Siemens and actively partners with its law firms and industry associations.

The Siemens Global Legal Innovation Challenge

The challenge called on all members of the worldwide legal department to submit innovative ideas for the improvement of the Siemens global legal department and its processes. Individual ideas could be liked, disliked, and commented upon by anyone in the global function. Based on the number of likes, views, and comments, an idea could advance to the next round of the competition.

We got together to decide how we should participate in the challenge. We quickly realized that over the past few years we had come up with a number of innovative processes and tools to help us operate more efficiently. So, about 80 percent of our submissions to the challenge were the kind that said, “This is how we do it, and here’s how it can be improved or adapted more widely in the global department.”

A screenshot of the challenge’s home page is shown in Figure 2. By the end of the challenge, 249 ideas had been submitted, with 55 of these coming from members of the Siemens Canada legal department. In total, there were over 23,000 views of the site, and the ideas were voted on 4,759 times and commented on 1,600 times.

Figure 2

Some of our favourite Canadian ideas included:

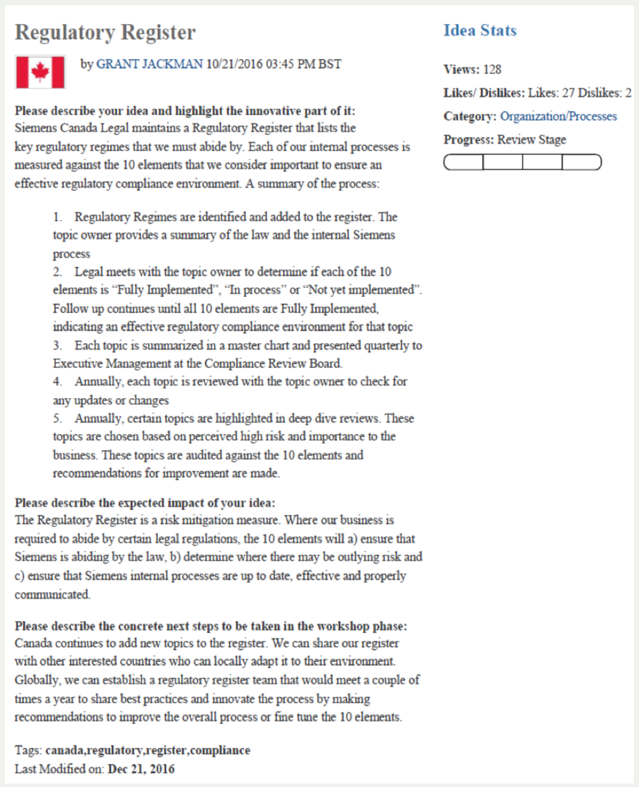

- A regulatory register describing our tool and process for reviewing the key regulatory compliance areas in Siemens Canada and assessing these against 10 characteristics of a strong compliance methodology (see Figure 3).

- A dashboard management process describing our previously mentioned dashboard system and suggesting how it could be implemented globally.

- Low and medium-value contracting processes that were two separate submissions outlining processes for dealing with low and medium value contracts that either eliminated legal review or drastically reduced its scope.

Figure 3

While a few of the Canadian ideas were among the final groups that qualified for global implementation, we were anxious not to lose the benefit of all the work we had done in coming up with our 55 submissions. We categorized the ideas and organized a department meeting offsite to decide on how we should proceed. Our categorization placed our ideas into five groups:

- Legal department management: 12 ideas

- Innovation in the legal department: four ideas

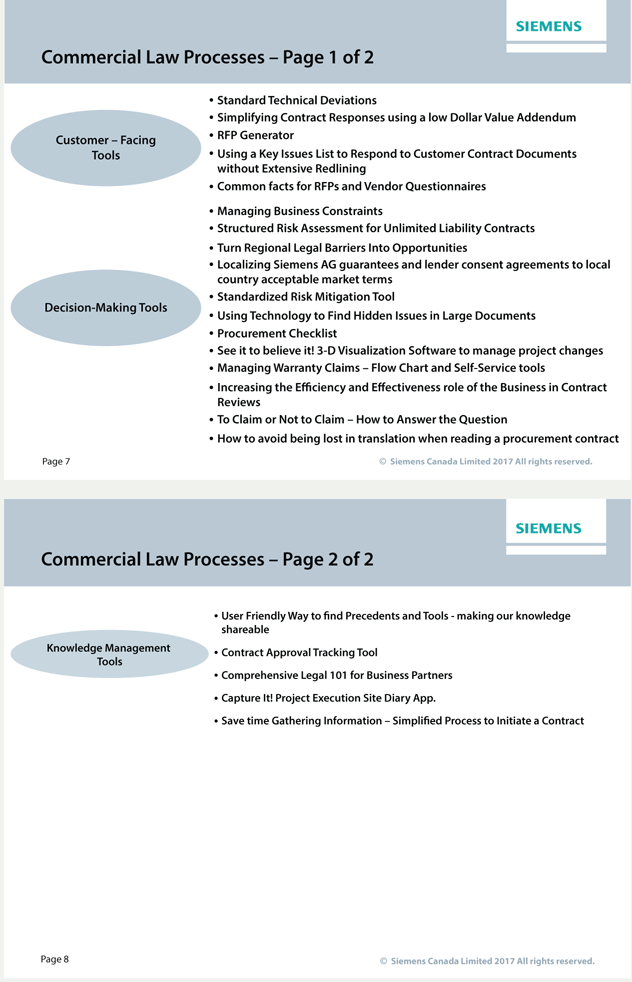

- Commercial law processes: 22 ideas

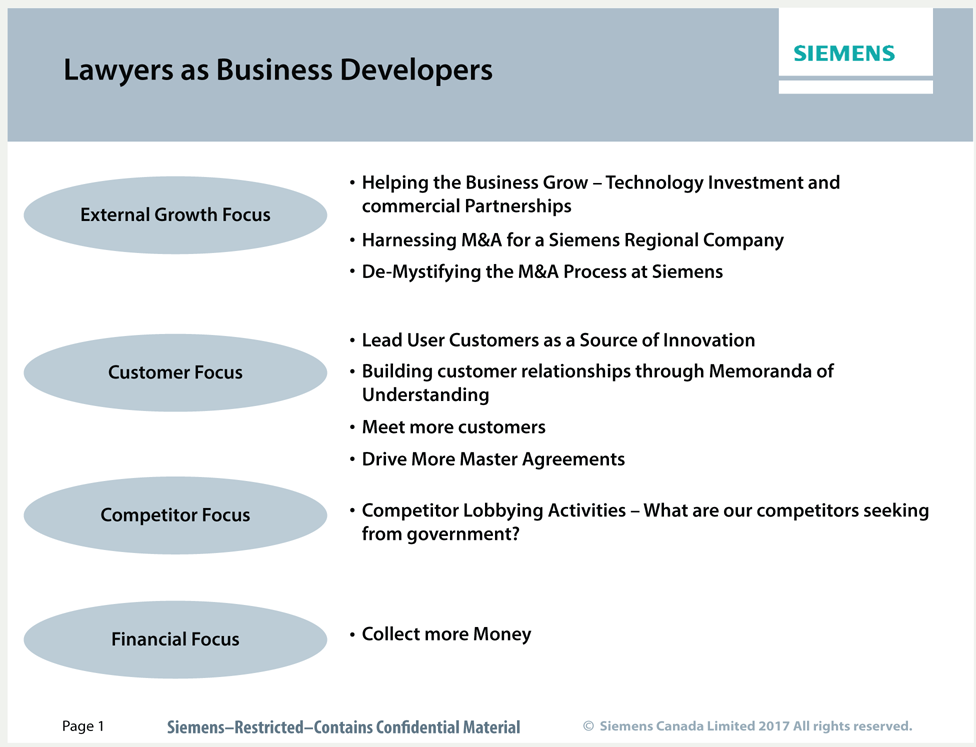

- Lawyers as business developers: nine ideas

- Regulatory and compliance processes: eight ideas

Two of the groups are profiled in the illustrations “lawyers as business developers” (Figure 4) and “commercial law processes” (Figure 5). The “lawyers as business developers” category has led us in two very productive directions. First has been an initiative in the department to improve our role as partners for the business. In furtherance of this, we have developed a “Portrait of Legal as Business Partner” that serves as guidance for the behaviours we expect of ourselves.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Secondly, several of our ideas for business development are now actually incorporated into the company’s initiative aimed at coming up with new business models that will help our businesses grow and increase revenue. What has become apparent to us is that our development of new outward looking approaches is a form of innovation that is key to advancing part one of our philosophy — behaving like owners of our businesses.

Our commercial initiatives grow out of the same philosophy. Each year, we work with our commercial team to identify opportunities to improve efficiency. We know the workload will increase as the business grows, but our legal resources will not. On a more fundamental level, however, we want our people to create efficiencies in order to spend more time focusing on complex and strategic work that brings the greatest value to the company. Not only is this better for the corporation, but it is also a key factor in creating strong engagement by allowing our people to use their skills to the fullest. Tasks that are dull or repetitive are rarely the highlight of anyone’s day; therefore they are usually the best area for innovation. We regularly schedule time as a group to identify approaches or tools we would ike to develop in order to spend less time in these areas. Here then is an example of innovation that supports part two of our philosophy — making ourselves more efficient and running our department like a business.

Our participation in initiatives such as the challenge has helped to create a deep innovation culture within our department. Our team recognizes that innovation isn’t just about picking digital tools that may be available. It begins by identifying a particular problem we want to solve and then looking for creative ways to create a standard solution. The majority of our effort is spent on solving the problem. Like good innovators, we often do not know what the solution will look like. It is an iterative, creative, and open process that can result in surprises that surpass our expectations.

In-house legal departments as “lead users”

When we analyzed our submissions to the challenge, we realized that a few of the ideas related to the process of innovation in the legal department. This served as a reminder to one of our authors, Richard Brait, of his time as a technology lawyer at Nortel Networks. He was a fellow in the group known as the Research Centre in Technology Management. Working with the group at the time was Eric von Hippel of MIT who had just released his ground-breaking work “The Sources of Innovation” (Figure 6). Its central thesis was that in many industries it is not manufacturers or technology suppliers who are the main innovators. In fact, there is a class of end user, which von Hippel labeled as “lead users,” who are the source of most innovation. More importantly, von Hippel’s research showed that such users were the main source of the most fundamental innovations. Hence he concluded that users tended to develop “functionally novel” innovations (i.e., first of their kind), whereas manufacturers tended to develop mainly “dimension of merit improvements” (making products smaller, faster, or cheaper).

Figure 6

What we realized is that in-house legal departments are prime candidates to be the “lead users” of the legal industry. Our various process innovations solve important problems for in-house departments, lawyers, and business people more generally. In many cases, especially for a smaller department such as ours, simple process innovation is enough; a strong process with the proper forms and an appropriate knowledge management vehicle is all we need. But, in those cases where our volume of work is greater, and the problem important enough, further automation may be worthwhile. It is in these areas that we also saw the potential of working with external parties to deliver a digital solution.

Engaging third parties to help automation

We identified three types of parties to work with for the purpose of automating some of our key processes:

- Our partner law firms — Our firms possess deep expertise in knowledge management, high volume needs, and a broad client base who might benefit from process efficiencies — making them an ideal innovation partner in many areas.

- A legal technology provider — These players have deep technology development knowledge and resources, the ability to adapt their in-house technologies and products to new uses, and a broad customer base that allows them to commercialize and then continually improve any products they develop.

- Our internal software development groups — These groups are able to work closely with us, keep developments proprietary, and are uniquely positioned to customize to our particular needs.

The following three examples illustrate the developments we have embarked upon with third parties.

Piloting of third-party software in an M&A deal

As a company that is engaged in frequent M&A and reorganization activity, we were interested in seeing if the use of new legal technologies could increase the efficiency and accuracy of our process. A recent transaction presented an ideal test bed — Siemens was acquiring a global company, headquartered in Canada, which had significant research and development operations and a large number of contracts around the world. We asked our candidate law firms to propose the use of new legal technologies in the transaction.

Our partner firm, Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP, piloted four new technologies:

1. A cloud-based program to organize and centralize transaction documents and automatically collect signatures, collate documents, and create record books;

2. Proof-reading software aimed articularly at defined terms and cross-references; and,

3&4.Two separate contract analysis tools that used artificial intelligence and machine learning to identify contract terms as part of due diligence.

The first two programs were used “live” on the transaction and generated significant efficiencies. We see both as potentially very useful for both ourselves and our firms. The document organization software, in particular, has promise for us internally in M&A, corporate reorganizations, and complex commercial transactions.

The most interesting results came from the use of the two contract analysis tools. We were not permitted to use these in the live transaction, but we were able to trial them after closing on the actual contracts contained in the due diligence room. The trial compared a manual review with a tool-assisted one. While both tools missed a material percentage of the clauses for which we were looking (between 30 and 40 percent), the end result was that the manual due diligence and the tool-assisted one achieved similar levels of accuracy, with tool-assisted review taking approximately half the time. The tools also enabled quick and standardized reporting of results — generating Excel and Word summaries in minutes.

Our law firm compiled a thorough report for us on the results of the pilots. They concluded that the results achieved with such tools will only get better as the tools themselves improve and the users achieve more familiarity with them. We concluded that the use of such tools will now be a requirement for our firms on future transactions, and we are examining how we can employ some of these tools internally.

Development of a claims management software tool with a legal technology provider

Thomson Reuters, a global developer of legal innovation tools headquartered in the Toronto area, heard about our participation in the challenge and asked if we’d like to meet to discuss potential collaboration opportunities. We gladly accepted the invitation and met to share some of our ideas. After reviewing a number of them, we agreed to collaborate in the area of claims management.

Our commercial group has worked closely with our businesses over the last few years to develop more robust change and claims management during project execution. As part of this, one of our recent innovations has been to create an interactive process flowchart for responding to warranty claims. The chart is hyperlinked to form fillable template documents.

Our collaboration with Thomson Reuters aims to develop a tool that will enhance and automate the whole change, claims, and warranty process. Our collaboration will bring value to both parties. We expect to have a tool that solves our particular problems, and Thomson Reuters has been able to learn in depth about the problems we face and the solutions that would benefit us the most. The development process consisted of a series of meetings, over the course of several months, as we defined our problem and the solution we envisaged. Over the course of development, in a very iterative process, Thomson Reuters proposed different options and we jointly discovered ways to exploit the full potential of their solutions. By the time we came to our beta launch, we had developed a tool that surpassed both our expectations. In addition to us gaining a tool, we acquired a deep understanding of how digital solutions are developed. We’ve been able to use these newly acquired skills in finding solutions to other problems.

The dragon’s den — internal development of a contract risk management tool

We’ve also had the opportunity to work directly with our internal Siemens software developers to create our own tool from scratch. Each year one of the divisions hosts an innovation challenge, primarily aimed at developing new products and solutions for customers. This year, corporate groups were invited to participate as well. We proposed a tool that redefined our approach to risk management in contract reviews.

Our entry was based on a process improvement that was a contender for digitization. Typically, when legal is engaged by the business to review a contract, we look at all potential issues in the contract and then discuss their importance with the business. Our customers prefer to see few deviations to their contracts, so we work with the business to discuss the risks we’ve identified and reduced our comments to focus on the real risks, as opposed to the theoretical or mitigable ones. We do this by gaining a better understanding of our offering, our relationship with the customer, and the risks that might materialize. The result is good, but the process can be time consuming for everyone.

In the Thomson Reuters experience, we were able to draw from the experiences of a solution developer to solve our problem. Here, members of our legal team had to define the solution, which meant defining the process flow, the logical content of the solution, and our ideal interfaces.

Given that Siemens has a wide portfolio of offerings, there is no “one size fits all” risk profile. We had noticed, however, that patterns of questions and answers repeat themselves. We began looking for a solution by working with the business to flush out the “hidden algorithms” we were using to review our contract mark-ups. Our process improvement was to then develop a series of questions to create a specific risk profile against which a contract could be reviewed. Noncritical risks would be noted, but our primary focus would be to address the real risks arising from the risk profile. Our entry focused on the efficiencies that would result from streamlined reviews allowing resources to focus on strategic matters and be more responsive to customers while managing risk in a well-considered manner.

Our customers prefer to see few deviations to their contracts, so we work with the business to discuss the risks we’ve identified and reduced our comments to focus on the real risks, as opposed to the theoretical or mitigable ones.

Much has been written lately about the T-shaped lawyer, a lawyer who has the ability to think outside of our core discipline and use expertise in the areas of technology, business, and analytics. In this case, members of our legal team drew on our collective experiences in programming, risk management, and business understanding, as well as our own interests in diverse topics such as information theory, user experience design, and human psychology. Our tool is currently being beta tested.

Next steps — a model for legal operations

In the Siemens Canada legal department, we have core legal operations tools that will be quite familiar to most in-house practitioners. These include:

- E-billing and law firm matter management;

- E-discovery; and,

- Filing and knowledge management systems.

In addition, each of our subject-matter practice areas has its own set of processes that can include tools, forms, guidelines, and checklists. We call these practice areas our “verticals,” and we have embarked on an exercise to identify these verticals, and for each of them to set out all of its processes — including any gaps. Figure 7 is the initial chart we came up with — identifying our verticals and their owners within the department. After identifying an owner for each vertical, we asked them to list all of their processes under the guidance of our legal operations professionals. Included in these lists are such data as the knowledge management vehicle being used and the frequency of use of the process.

Figure 7: Leads for verticals (practice/subject

matter areas)

| VERTICAL | TO INCLUDE: | LEAD |

| Customers – Pre Contracting | …… | |

| Customers – Bid Response | …… | |

| Customers – Contract Review | …… | |

| Customers – Financing | Financial guarantees | …… |

| Customers – Post-Signing matters | Claims management | …… |

| Other Contracts | Master and frame agreements, agency, distribution, and consulting agreements | …… |

| Siemens Internal Agreements | ZRG, new collaboration model, sales rights agreements, service level agreements, intellectual property transfers | …… |

| Corporate Governance | …… | |

| M&A | …… | |

| Regulatory | Lobbying, government procurement (AMF, Federal Integrity Regime) | …… |

| Employment | Employment litigation | …… |

| Pensions | …… | |

| Litigation – Commercial and Generic | …… | |

| Procurement | …… | |

| Real Estate | Environmental | …… |

| Risk | RIC controls processes and Legal Risk Register | …… |

| External Counsel Relationships | …… | |

| Support for other corporate departments (A/C, Communications, Compliance, Information Technology, Business Excellence, Tax) | Compliance includes data privacy and anti-trust | …… |

Note: Each vertical should consider whether there are approval processes, signature authorities, or key Siemens rules that should be included

We expect the outcome of this exercise to be twofold:

- The identification of a knowledge management architecture to house and manage all of our vertical processes as well as our core tools. On this front, we are working with the knowledge management group at one of our partner law firms to do a legal design exercise aimed at defining our overall knowledge management approach.

- Identify areas in the verticals suitable for automation, as well as any common needs that may allow us to select or develop a tool to help automate several of the vertical processes — an example of this might be a “form-filling” tool.

In-house innovation

It’s natural for those of us in corporate legal departments to think of innovation as something done by others — including the engineers and computer scientists in our own companies and the legal technology suppliers from whom we buy tools. But as we’ve learned at Siemens, there is significant potential for innovation within our own ranks. In-house departments are ideally positioned to design processes and systems that solve the problems they face and allow them to operate more efficiently.

We’ve also discovered that modest size is not a barrier to innovation. In many cases, innovative processes can increase our performance substantially, even when these are not automated but instead rely on the traditional devices of standard forms and checklists. But where automation is justified, our early experiences indicate that law firms and legal technology suppliers can be excellent development partners. The key to successful innovation is understanding which problems are important and which process improvements will generate real values or efficiencies. When that is clear, all the stakeholders in the process are likely to be enthusiastic participants.

In-house departments are ideally positioned to design processes and systems that solve the problems they face and allow them to operate more efficiently.

As detailed at the outset of this article, our philosophy as a department is to behave like owners of the businesses we work with and to run our department like a business. A key to our success is to ensure that our innovation is directed at these two objectives. Thus an examination of our key initiatives will show several that are focused on the external objectives of our businesses and also many that are directed to making our function more efficient.

Further Reading

1 Eric von Hippel, The Sources of Innovation, Oxford University Press (1988).

2 Richard A. Brait, “Lead Users as a Source of Innovation,” Oxford International Journal of Law and Information Technology, Vol.12, No.2 (2004).