CHEAT SHEET

- CCPA. The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) goes into effect on January 1, 2020, and gives California consumers five new privacy rights: to know what personal information is collected about them; whether and to whom their personal information is sold/disclosed and to opt-out of its sale; to access their collected personal information; to demand a business delete their personal information; and to not be discriminated against for exercising their rights under the Act.

- Personal information. The CCPA defines personal information as “information that identifies, relates to, describes, is capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household.”

- Overlap with GDPR. Due to the similarities between the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the CCPA, companies that implemented compliance programs for GDPR can use parts of their program to meet some of the CCPA requirements.

- Affected companies. The CCPA applies to for-profit businesses that collect and control California residents’ personal information, do business in California, and meet one of the following: have annual gross revenues in excess of US$25 million; receive or disclose the personal information of 50,000 or more California residents, households, or devices on an annual basis; or derive 50 percent or more of annual revenues from selling California residents’ personal information.

After fewer than two days of debate, on June 28, 2018, the California Legislature passed the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA or Act). In reaction to recent privacy incidents and in an effort to stave off an even more onerous ballot measure, this sweeping legislation created significant new privacy rights for consumers to request their personal information from businesses that collect their data. Due to the size and importance of California, this Act could serve as a model for other states and nations. Its effect will be felt well outside of the US state, and may even become the basis for global legislation. Perhaps most importantly, the CCPA provides a right of private action, which allows an individual (or individuals) to sue in the event of a data breach, potentially spurring substantial class action litigation. With a relatively short deadline before coming into force — January 1, 2020 — coupled with potentially significant penalties, companies with the assistance of corporate counsel need to start developing a CCCPA compliance program now.

“There is a growing campaign by the plaintiffs’ bar to target data privacy and security in the hopes of striking it rich in a new goldmine on the level of the asbestos litigation of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.”

— The US Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform

Quick overview of the CCPA

This article is not intended to provide an exhaustive review of the entire Act (the actual legislation can be read at leginfo.legislature.ca.gov). Nonetheless, it summarizes some of its requirements, together with a September 2018 amendment. While the Act goes into effect on January 1, 2020, it won’t be enforced until the Attorney General publishes regulations, which are not required by law until July 1, 2020; six months after the effective date.

Summary of CCPA requirements

The CCPA provides California consumers with five new privacy rights. Under the Act, California consumers will have the right:

- To know what personal information is collected about them. Consumers will have the right to know the personal information a business has collected about them, its source, and the purpose for which it is being used.

- To know whether and to whom their personal information is sold/disclosed, and to opt-out of its sale. Companies that provide or make consumer data available to third parties for monetary or other valuable consideration are deemed to have sold the data and will need to disclose this. Subject to certain exceptions, consumers will then have the further right to opt out of the sale of this information by using the “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” link on the business’s home page. This link is required by the Act. Moreover, those individuals 16 years and under must opt-in to have their information sold.

- To access their personal information that has been collected. Consumers will have the right to request certain information from businesses, including the sources from which a business collected the consumer’s personal information, the specific elements of personal information it collected about the consumer, and the third parties with whom it shared that information. Once the request is made, businesses must disclose the requested information free of charge within 45 days, with extensions of time available in certain circumstances.

- To have a business delete their personal information. With some exceptions, such as for transactions, legal purposes, and solely internal uses, consumers can request that a business deletes their collected information. The business, in turn, must inform service providers with whom they’ve shared the data to also delete the consumer’s personal information.

- Not be discriminated against for exercising their rights under the Act. The CCPA gives consumers the right to receive equal service and pricing from a business, even if they exercise their privacy rights. As such, businesses may not “discriminate” against consumers for exercising these privacy rights.

Fines for violations include:

- US$2,500 for unintentional and US$7,500 for intentional violations of the Act. However, for now, only the California Attorney General can pursue these penalties.

- US$100-US$750 per incident, per consumer — or actual damages, if higher — for damage caused by a data breach. Under the Act, consumers now have the right to sue for a data breach.

While these fines may appear relatively low, it is important to keep in mind they are per violation. It is not uncommon for a data breach involving a hotel or department store, for example, to affect thousands if not tens or hundreds of thousands of consumers, in which statutory damages could easily reach millions of dollars.

The new right of private action for a data breach will likely result in significant class action litigation. The US Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform commented: “There is a growing campaign by the plaintiffs’ bar to target data privacy and security in the hopes of striking it rich in a new goldmine on the level of the asbestos litigation of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.” While many US companies have hoped to fall under the radar of European regulators who passed the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2016, US companies are far more visible to the US plaintiffs’ bar.

Figure 1. Many other US states and nations may adopt legislation similar to the CCPA.

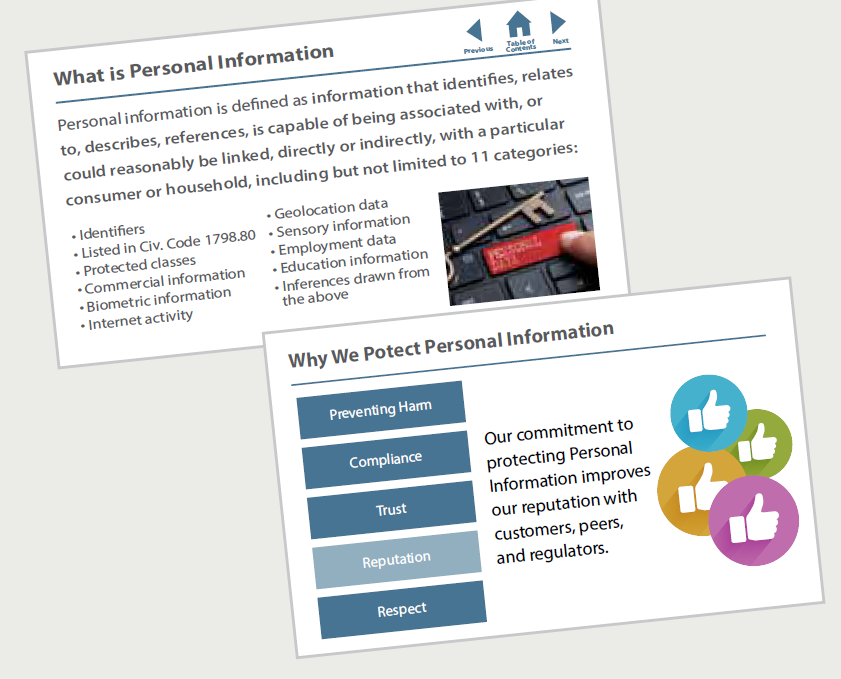

What qualifies as “personal information”

The CCPA expansively defines personal information as “information that identifies, relates to, describes, is capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household.” The Act then lists eleven broad categories of information that are personal information. Examples include obviously personally identifiable information such as name, address, phone number, email address, social security number, driver’s license number, etc. But the Act also includes less obvious “personal” information such as biometric, geolocation, and professional or employment data. While the definition of personal information may be further clarified by the Attorney General, or even reduced in scope by future legislation, in any event, it will likely continue to be broader in scope than any existing law or regulation.

Who has to comply with the Act?

As a threshold matter, the CCPA applies to for-profit businesses that collect and control California residents’ personal information, do business in California, and meet one of these three requirements:

- Have annual gross revenues in excess of US$25 million; or,

- Receive or disclose the personal information of 50,000 or more California residents, households, or devices on an annual basis; or,

- Derive 50 percent or more of annual revenues from selling California residents’ personal information.

Companies that collect personal information for commercial conduct that takes place “wholly outside California” are exempt from the Act, although identifying a consumer in California, and then later collecting personal information when that person is outside California, would not be exempt.

The Act also exempts the following information from its title including:

- Information collected, processed, used, or shared pursuant to the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) or California’s Financial Information Privacy Act (FIPA);

- Protected health information pursuant to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); and

- Credit report information pursuant to the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).

While businesses without a commercial presence in California, or who don’t engage or sell to California consumers, may express relief at not having to legally comply with the CCPA, their ease may be short-lived.

In many cases, it may be difficult for companies to segregate California consumers from other consumers, especially regarding online information gathering. Many businesses may also feel pressured to offer these privacy protections beyond California when non-California consumers expect similar privacy rights. It may be difficult to justify providing these protections to some customers but not to others.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, other states may follow California’s lead if history is a guide. California, in 2003, was the first state to introduce a data breach disclosure law, which has been emulated by every state since then. Likewise, it is reasonable to expect other states to provide more privacy rights through similar legislation.

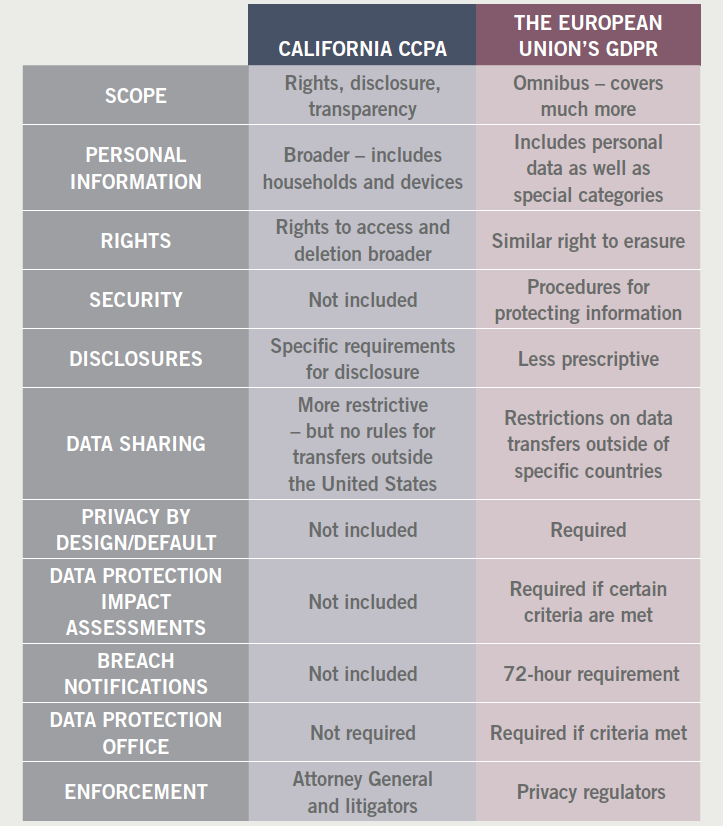

Comparison with GDPR

The European Union has been at the forefront of consumer privacy since the 1996 Data Privacy Directive to the current GDPR, which provides even greater privacy rights to EU residents. Some even refer to the CCPA as California’s GDPR.

While there a number of similarities between the two, there are also many differences. Table 1 provides a comparison.

Table 1. CCPA compared to the European Union’s GDPR

Companies that implemented GDPR-level compliance can leverage parts of their program to meet CCPA requirements. However, additional program development for CCPA will still be required.

Should implementation begin even though the CCPA may change?

The Act goes into effect on January 1, 2020 — despite the fact that its implementing regulations need not be issued by California Attorney General Xavier Becerra until July 1, 2020 — six months after the effective date. While there are certainly provisions of ambiguity that will require clarification, businesses shouldn’t use this as an excuse to not begin their compliance efforts. Unfortunately, unlike other privacy laws that allow years to become compliant, the CCPA offers only 18 months before it comes into law in full force. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to begin implementation now and then adjust if and when Attorney General regulations are adopted and if the Act is amended. Waiting until there is certainty will cause businesses to miss the January 1, 2020 deadline.

Key program considerations

Special information governance considerations

While consumers will have the right to request that their personal information be deleted, there are carveouts to this right including:

- For information excluded from the Act and covered by other regulations such as the GLBA, the Driver’s Privacy Protection Act, and California’s FIPA.

- When personal information is necessary to be maintained pursuant to one of nine CCPA exceptions. If, for example, information is needed for legal purposes, completing a transaction, detecting fraud, or solely for internal use, it need not be deleted.

- Record retention laws and regulations may require companies to retain records for a certain number of years. These legal requirements can override consumer deletion requests, even if the record in question contains personal information otherwise covered by the CCPA.

- If a deletion request is made for data under legal hold because of litigation or regulatory inquiry, while the hold is in effect the documents, including data, must be retained. Only after adjudication should the pending deletion request be considered.

While under California’s Act certain exceptions exist, these same exceptions may not apply to other states, or under federal legislation. Therefore, businesses should build a flexible program that can comply with various privacy laws.

Common roadblocks to successful program execution and compliance

As part of good program planning, it is useful to identify potential roadblocks at the outset that could either halt or delay program completion. When it comes to implementing a privacy program, common pitfalls include:

- Policy-itis: A common roadblock to privacy programs is focusing on the development of a privacy policy to the exclusion of policy execution. This risk is particularly acute under the CCPA as the final implementation guidelines from the attorney general will likely be released six months after the Act’s start date. Compliance is achieved not just through having a policy, but also by faithfully implementing the policy without delay.

- Siloed approaches: Effective privacy programs require a team approach. The wider the team’s membership, the greater the buy-in, or support, the program will have. A strong team includes privacy specialists from legal, compliance, IT, and other business units. Any single group that takes on this task by itself is likely to fail.

- Manual or unworkable processes: Manually responding to personal information access and deletion requests is likely to become overwhelming quickly. Organizations will need to implement an automated, streamlined approach.

- Starting too late: The CCPA provides a short time frame before consumers can exercise their newfound privacy rights on January 1, 2020. While the attorney general may not begin enforcing the CCPA until July 1, 2020, if their regulations are delayed, ignoring a consumer’s request could lead to complaints to the attorney general. Organizations that start creating their program too late run the risk of not completing it on time.

All of these pitfalls can be avoided with a well-thought out CCPA project plan that engages the right stakeholders and contains reasonable timeframe and milestones.

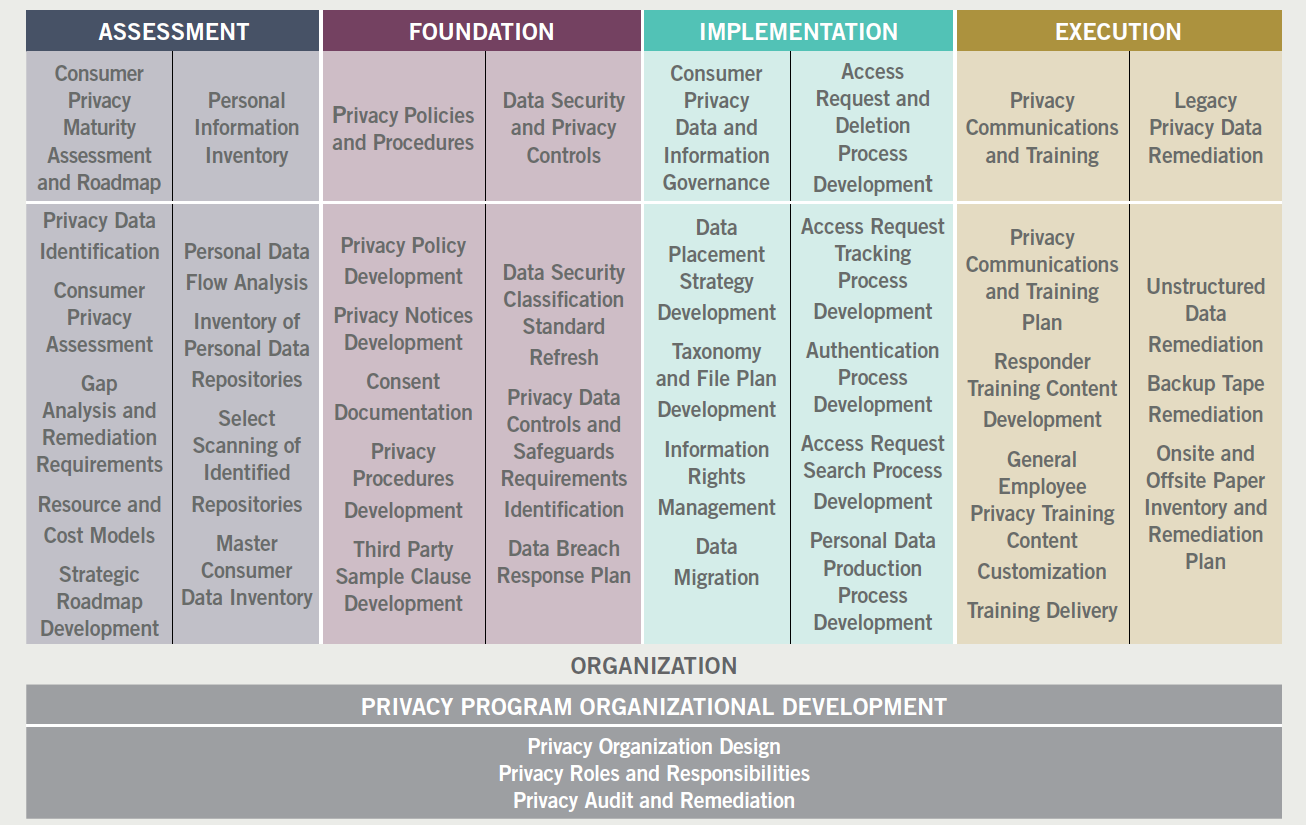

CCPA action plan overview

Creating a CCPA-compliant privacy program involves a combination of policies, processes, application of technology, and user training on privacy responsibilities. These activities are best broken out into discrete steps. Figure 2 provides an example of a project plan.

Figure 2. Sample project plan for implementing CCPA compliance.

Figure 3. Sample project plan for implementing CCPA compliance.

Creating an assessment roadmap

Organizations should start with an assessment process that in turn feeds into a program roadmap. Through a high-level interview process, the assessment reveals the types of personal information a business collects, how they manage and protect it, and the current processes in place to communicate with customers and regulators on privacy compliance. This includes the reporting of data breaches as well. The information learned during the assessment can then be used to identify gaps between an organization’s current state and the state required for CCPA compliance. This leads to a roadmap to address these gaps. The roadmap should also contain resources required for each step, any new technology that may be required, as well as cost projections for each step. A timeline and milestones will help achieve compliance before the 2020 deadline. Equally important, the assessment and roadmap process engages a number of key stakeholders early in the project, which is always required for the successful implementation of a program.

Developing a personal information inventory

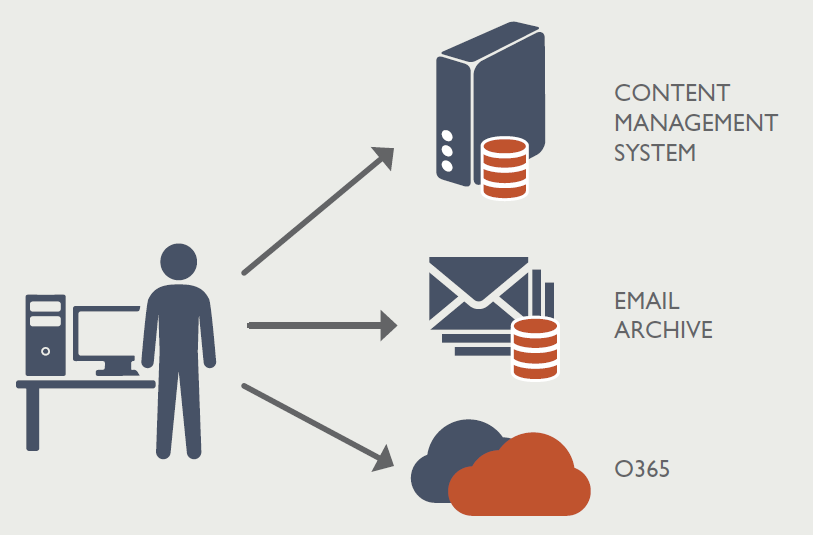

Critical to compliance with the CCPA is being able to track both how personal information is collected and flows through an organization, as well as where it is stored. Businesses will need to create a personal information inventory that lists all relevant processes involved in the collection, and use of, personal information. The inventory should reveal those who have access to the personal information, to whom the information is transferred or shared outside the company, and how long the personal information is stored in each location.

Figure 4. A personal information inventory should take a two-pronged approach reviewing both work flows and repositories.

The personal information inventory process can identify the patterns of information flow and storage that may be unique to your business. This can help you identify personal information. Some of it can be identified through searches for known data sets, or patterns, such as social security numbers, addresses, driver’s licenses, etc. Other types of personal information, such as inference data, may require more advanced search techniques.

Once the personal information and its respective data flows are identified, the inventory should also distinguish each location where such information is stored. This may include databases, email, and internal file shares, among other locations. Often, employees will extract data from a database, for example, and store that as a file on their desktop. The inventory should include both designated locations of this data, such as the original source, plus any inadvertent or duplicate copies.

Defining privacy policies and procedures

The Act will require many businesses to update or create additional privacy policies and implement a series of privacy procedures that disclose these new privacy rights. The documents that may need to be created or updated include:

- Privacy policies and notices;

- Consent notices;

- Deletion procedures;

- Data security classification standards;

- Privacy impact assessment; and

- Data breach/incident response plans.

Figure 5. The Act requires that businesses develop a privacy policy that makes certain disclosures to consumers at the time personal information is collected.

In some cases, these new policies may simply require updating existing privacy policies. In other cases, companies may have to develop entirely new processes, such as a procedure to respond to consumer information access requests. The Act also calls for specific processes, such as placing a prominent “Do Not Sell” or “Opt Out” button on a company’s website.

Creating data security and privacy controls

In addition to consumer’s new privacy rights, the Act provides statutory damages in the event of a data breach. Consequently, businesses will want to review and strengthen their management and security of personal information and implement data security and privacy controls. While the exact protection measures will depend on the type, medium, and location of the personal information, typical controls include:

- Preventing or controlling data transfer between repositories;

- Tightening access controls;

- Securing and encrypting data when stored;

- Preventing data from being shared, printed or stored elsewhere; and

- Scanning repositories for inappropriately stored personal information data.

This action highlights the importance of the previous step: creating a comprehensive personal information inventory that maps out all locations where this information is stored. This is critical as a breach can involve not only repositories of record, but also secondary copies of data in less protected areas.

Data and information governance

Not only is personal information likely to reside in databases, but also in unstructured media including files on desktops, and in file shares. Databases containing privacy information should be identified and their access controls tested. For unstructured data, desktops and file shares do not provide adequate protection. This information needs to be moved to more secure repositories such as an enterprise content management or a document management system. This includes developing taxonomies and/or file plans that contain a privacy/security schema, in order to properly organize and classify the information in these repositories.

Figure 6. Information stored in cloud-based repositories requires the same protection as any other information or document. These repositories should also have an appropriate file-protection plan and security schema.

Typically, a personal information inventory will identify many different locations with privacy information. Businesses should not expect to secure everything all at once. Instead, a company will need to prioritize their efforts. To start, companies should prioritize data stores with large amounts of personal information. When choosing the appropriate repository to store this information, organizations should look at repositories with built-in controls. It is recommended that implementation projects be piloted against smaller data sets and then be rolled out to the larger enterprise.

Do not forget about paper records, either onsite or in offsite storage facilities. These documents can and do contain significant personal information. CCPA disclosure and deletion requirements include information on these hardcopy documents.

Access request and deletion process development

Many processes are necessary to support consumer access, production, and deletion requests. These include:

- Authentication processes: Authenticate the identity of a requestor.

- Search processes: Determine the consumer’s personal information and where it resides. Many businesses may need to increase their digital search capabilities to avoid time-consuming, ad-hoc processes.

- Production processes: Produce and deliver requested personal information securely. Many may need to improve their technical security.

- Deletion processes: Respond defensibly and compliantly. Manage deletion requests and coordinate with records retention and legal hold requirements.

- Tracking processes: Track and manage all consumer requests.

The more effective the data and information governance capabilities discussed in the previous step, the more efficient and cost-effective deploying these processes will be. In contrast, poor data and information governance will result in burdensome processes.

Conducting privacy communications and training

Once a company has its roadmap, policies and processes, tools, and technology in place, a critical task remains: employee behavior change management. Change management is a formal discipline that combines messaging, communication, training, and auditing to get employees to follow a new process. Often, as part of a revamped privacy program, organizations will implement change management to ensure appropriate handling of privacy information. When businesses effectively apply change management, otherwise stodgy, disinterested, and uncooperative business groups get on board.

Figure 7. Privacy training should include both targeted training for those with specific privacy-related responsibilities, as well as general training for all employees.

A business’ CCPA program should train staff with specific responsibilities for handling personal information, as well as employees who will respond to consumer information access requests. Actually, it is a good idea for all employees to receive some general privacy training. Such training should emphasize why privacy and data security is important to the company’s clients and customers, and the company’s overall responsibilities for handling personal information.

Disposing of legacy data

Retaining personal information that is obsolete, expired, and unnecessary for legal, regulatory, or business use increases the risk of CCPA non-compliance, and increases a company’s exposure should a data breach occur. Likewise, implementing personal information deletion requests in environments with large amounts of legacy data is both difficult and expensive. To that end, privacy and other information governance programs should implement ongoing disposition of old, unneeded documents and data. This legacy deletion should encompass older structured data in databases, unstructured data including files on file shares, desktops, and within SharePoint and other content management systems, legacy semi-structured data such as email, plus inactive data held in backup tapes, and onsite and offsite paper records.

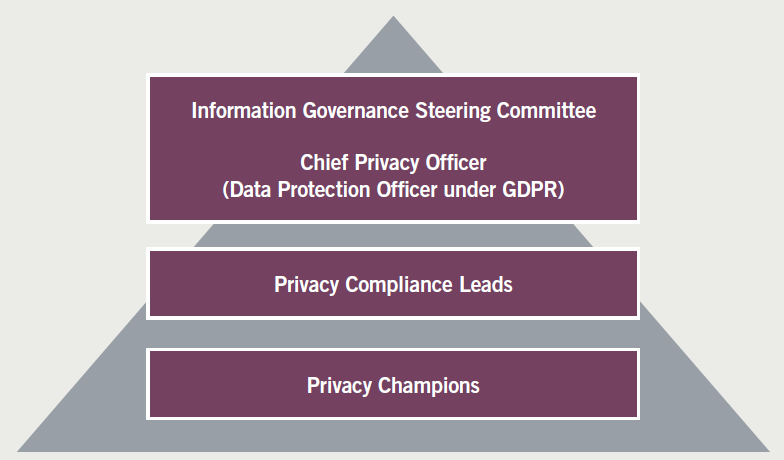

Developing a privacy-focused organization

More data has been created in the past few years than in the entire history of the human race. And businesses are investing heavily in collecting and analyzing this information leading to big data being a top business priority and growing into a multi-billion dollar industry. The amount and invasiveness of this information is so staggering that consumers, and by extension lawmakers and regulators, are noticing and trying to place conditions on how businesses can use this revolutionary amount of information.

Figure 8. Sample privacy hierarchy within a company

Companies will increasingly need to be good stewards of consumers’ information. To do so, comprehensive privacy programs will be necessary. A privacy program is not a check-the-box operation. It is a living program with ongoing responsibilities throughout the organization.

The CCPA may be the catalyst for companies to start developing their own privacy program. When organizing the CCPA implementation project, there are important decisions for senior management, including:

- Identifying the most effective coordinators;

- Identifying the most invested stakeholders;

- Organizing a steering committee; and

- Identifying who should be part of the steering committee, including executive-level personnel.

The creation, or modernizing, of a matrix structure of the steering committee for CCPA efforts can then be used for ongoing privacy activities and to support other information governance responsibilities.