Cheat Sheet

- Time tested. Benchmarking and performance improvement have been universally applied since the 1950s as all enterprises strive to their next level.

- Be aware. Once you fail to look up, you think you’ve reached the highest point.

- Take charge. Changes must be defined, measured, and carried out by you, rather than to you.

- Analyze it. If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.

The ACC-Smarter Law Solutions free benchmarking and consultation service for ACC members has proven to be a hit since its launch in 2019.

“Meeting with ... Smarter Law was an eye-opening process, … an excellent way to get a sophisticated general assessment of how an efficient legal department can be managed, with real-world implications that I can take, and look to implement, as we try to improve our own legal operations (how we support our clients, what we do, reducing risk in a smart way, etc.)”

- Mid-size information technology company

“Here’s a big shout-out! That was well worth our time. [Smarter Law] was prepared, engaging and very informed.”

- Large financial services company

“Your comments are more insightful than you can even know. Thanks again to you and the ACC for this very helpful exercise!”

- Mid-size government agency

But rather than regale readers with the positive, we thought that it would be more illuminating to respond directly to certain well-held hesitancies expressed by those considering a basic benchmarking or performance improvement process.

So, typical reservations were gathered and sent to Smarter Law Solutions CEO Trevor Faure for his candid counsel.

Why benchmark at all?

“Our company is profitable, and we’ve had no major compliance issues. We’re doing well enough. Why conduct a benchmarking assessment?”

All leading businesses maintain a process of continuous improvement, which has many different forms: from Six Sigma since the 1950s, Agile and Design more recently, along with countless other titles and acronyms.

Ultimately, these processes are no more than common sense plus data. They define one’s mission, measure current performance of that mission, analyze what the measurements show, and improve the areas that the analysis highlights as necessary. For legal departments, benchmarking is this measurement. In any enterprise, any current level of performance can be examined in order to be improved upon or, more philosophically.

Once you fail to look up, you think you’ve reached the highest point.

More prosaically though, most enterprises have stakeholders for whom “profitable” is never the same as “profitable enough,” especially when “even more profitable” is achievable through common sense plus data. So continuous improvement has become a given, regardless of the current performance cycle of a business.

Once you fail to look up, you think you’ve reached the highest point.

A persistent preoccupation of in-house counsel is, “How can we speak the business language and earn our place at the business table?"

Continuous performance improvement is a basic business language; our peers in the C-suite will always appreciate being joined in their trenches of performance targets by lawyers who are similarly willing to be held up to metrics, instead of being perceived as being “above the fray” at best or a “a bottleneck tied with a bow of red tape” at worst.

“What if our peers have a lower legal spend as a percentage of revenue than us? What if we have twice as many lawyers per $1B in revenue than our peer companies? How do we know that their performance as a legal department is better than ours?”

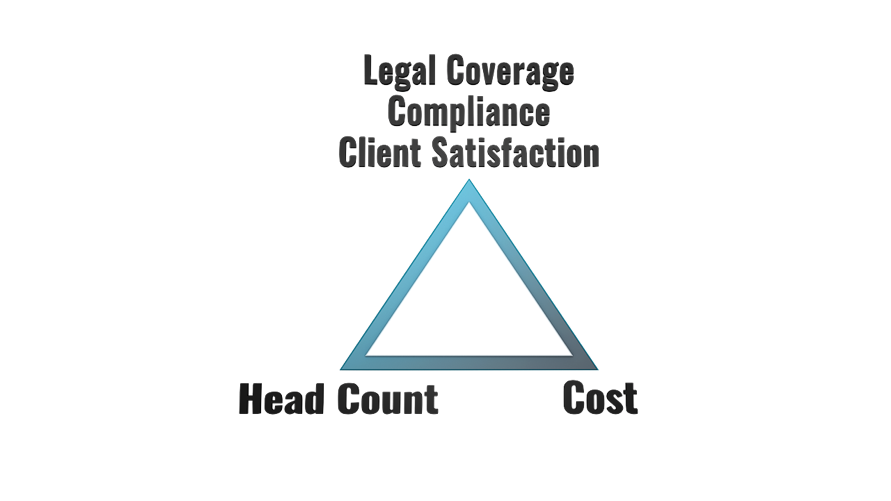

It would be absolutely correct to say that an isolated datapoint or benchmark is next-to meaningless as a comparative tool. Any function or work product is a result of resource inputs and work outputs. In the case of legal departments, the resource inputs are the headcount and costs (internal and external), the work outputs are the legal services covered (contracts, litigation, advice, etc.,) and resulting levels of compliance and client satisfaction.

Thus, a cost input benchmark such as, say, legal spend as a percentage of company revenue, has to be triangulated with its output results in order to make a meaningful comparison with other legal departments. A car that costs 10 cents-a-mile to run (input) and can safely and comfortably transport seven people at 150 mph (output) is a better performer than one that costs US$1-a-mile to run with half the space, safety, and speed.

“Why does it matter to operate optimally? HR doesn’t. Finance doesn’t. Why does legal need to? Why should we be the ones to transform our department and save the company money?”

Comparison with other underperforming departments is very much a question of principle. For example, the Smarter Law principle is to “transform busy lawyers into business leaders,” but not all lawyers want to lead the business performance of their own department, let alone set an example to the general business that their department supports.

Instead, we describe an alternative principle: that of the “comfort of the lowest common denominator” wherein related mediocrity (i.e., the supposed HR or finance department in the question) is a motive for doing nothing.

Those holding this principle might give some consideration to fulfilling longer-term career goals within or beyond the company before settling for the status quo indefinitely. Or face the consequence of postponing an improvement initiative until obliged to do so (for inevitably negative reasons).

Another long-term scenario is that the business may eventually decide that wholesale performance improvements are required across the board and back office, particularly if the major stakeholders themselves change or their operating principles have to change in order to meet evolving market conditions. In such a scenario, taking the initiative by owning an improvement process would mean that eventual changes will be defined, measured, and carried out by you, rather than to you.

Can I trust the benchmarking?

“To be confident in results of the assessment, we need to be sure the data is based on companies that are a true apples-to-apples peer group.”

ACC Benchmarking is the largest data set of its kind in the world, from which tailored sub-divisions are produced on request to closely reflect the industry sector, revenue size, and geography of your company.

Two companies are rarely exactly alike, but your company is also subject to competitive pressure, investor scrutiny, and/or market analyst reports — which always comprise other comparable companies for the purposes of measurement and analysis of your company’s performance.

In both financial and customer markets, no companies are regarded as truly “unique” but have a range of transferable qualities or common interests with certain peers — albeit sometimes very few of them (e.g., Faure was global general counsel of EY, part of a “Big Four”).

Even within a group of comparators there will still be a high-to-low range of four-quartiles, within which a company may deliberately target its performance. For example, I once worked for a single-digit margin business that prided itself on always being in the lowest quartile of benchmarking in other vital measures such as salary compensation as it was proof of its lean day-to-day operations with the employees’ upside coming from a rocketing stock price instead.

“The assessment makes large claims based on so few metrics. Can you really produce an accurate estimation of our potential savings with such a limited amount of information?”

Firstly, operating optimally need not be singularly or predominantly about saving primary legal costs. Maximizing the efficiency and impact of the same legal spend can result in improved client satisfaction, contract turnaround times, and cash flow, along with reduced customer disputes and wasted management time.

Optimizing legal resources is ultimately as much about increasing the personal potential of individual lawyers and the quality of their work as it is about decreasing its cost.

Benchmarking only provides directional, rather than definitive, guidance. In other words, it identifies how a function may currently be higher or lower than its industry competitors. It thereby provides some directional reassurance that a given function may decrease or increase its scale and still be able to operate reliably and competitively, given its market peers.

“Our company is unique. How do we know that your methodology will work with us?”

There are a few reasonable indicators:

- Your company already deploys process and performance improvement methodologies in some other aspect of its operations, and so it is not uniquely impervious to being defined, measured, analyzed, and then improved.

- These universal steps are merely common sense plus data, so they will apply to any practical activity.

- Despite being universally applicable, each step is still exclusively driven by the very particular circumstances of your legal function, as revealed by each preceding step. In Smarter Law alone this results in potentially 14,000 different solution paths, where five basic definitions are measured in six different ways, producing nine different analyses, 10 different improvements, and so on. Therefore, the improvement permutation that applies to your company may not be entirely unique but will be very highly tailored from 14,000 proven options.

- Hundreds of successful transformations around the world over 20 years, numerous industry awards, and so on.

How do I justify taking on a consulting engagement?

You may not need to justify engaging consultants because you may not need to engage consultants at all! For any of several reasons:

- Benchmarking might well show maximum qualitative and quantitative outputs for minimum resources inputs such that major transformation is not objectively justifiable.

- Your legal function already has decades of legal performance improvement experience and hundreds of successful transformations under its belt, such that any improvements are already reliably underway or well within reach.

- Any consulting engagement is on a “no win–no fee” contingent basis so that any fees are only payable as a result of (and indeed, from) savings or other tangible improvements generated by the engagement. This type of engagement is described as “washing its own hands” due to its guaranteed net financial benefit.

“If I suggest to company leadership that we should take on a consulting engagement to ‘improve performance,’ then leadership will wonder why we just hired a legal ops professional and there will be an acknowledgment that we are not performing well enough.”

The performance advisory industry is a multi-billion-dollar global profession and all of the world’s leading companies use it for different aspects. For example, it is estimated that at any given time, each of the “Big Four” professional service firms supports approximately 80 percent of the Fortune 100 companies, meaning that many such companies use more than one advisory consultancy at a time.

High-performing companies and functions do not regard intermittent support from independent specialists as a sign of “failure” any more than personal trainers only help the chronically unfit and unwilling. Instead, it is a sign of the maturity of both the professionals seeking to reach the next level of performance and that of the best consultancies.

However, all that being said, there is also a reasonable level of skepticism about consultants partially due to several factors:

- The low bar of entry to consultancy, thus being open to non-experts and unproven theories, to paraphrase George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman: “Those who can, do. Those who can’t, consult.”

- Maslow’s “Law of the Instrument”: When they are selling hammers, every problem looks like a nail — namely that for certain consultancies that are also selling a prescribed solution (i.e., legal advice, legal tech, interim staffing, contract management, etc.). Hence whatever question you think you might have, their answer will invariably involve a product or service from their core business but not necessarily your first, best answer. At best, consultants should be solution-agnostic with a transparent process that could lead to any solution that works best for the client whether they have a financial interest in that solution or not.

- The consultant’s tempting opportunism to find problems where few exist. Valid advice sometimes comprises the analytical findings: “Nothing to see here” or “You can do it yourself” even if this might result in little or no further consulting work. This is why the basic ACC-Smarter Law service is free to ACC members.

“… then leadership will think I’m not qualified to run my legal department.”

There are a few sensitive truths worth exploring here:

Even if the performance improvement methodology and profession only came into widespread existence in the 1950s, the legal operations role is much more recent and nascent. Less than one percent of all companies surveyed even have a legal ops function.

Less than one percent of all companies surveyed even have a legal ops function.

Despite the positive proliferation of legal ops professionals, most have been in their role for less than a decade and very few have undertaken this role in two or three different companies, unlike say finance directors, procurement leaders, or even HR professionals. For example, the Institute of Supply Management was founded in 1915 and administers two separate, exam-based professional certifications to practice in procurement.

Similarly, unlike these other examples, the fact that there isn’t a universally-recognized qualification for, or consistent path into a legal operations position means that different individuals bring different strengths — some are finance, procurement, or performance improvement professionals translating these disciplines to the practice of law. Some are legally qualified professionals adding data analytics or technology expertise to their skillsets, and some have backgrounds in administration, procurement, or general management.

These truths may create a tension wherein a legal ops professional eschews external support in order to “prove” their capability, often for just the first or second time in a legal ops role, to sometimes cynical, overworked lawyers.

Furthermore, the broad scope of disciplines required for performance improvement in law is underappreciated.

Smarter Law is described as spanning “emotional intelligence to artificial intelligence” as too often the profession focuses on technology and “left brain” data analytics as routes to improvement, missing the vital “right brain” human factors of personal development and behavioral change — and vice versa.

A legal ops professional may be more or less qualified in one aspect or another, so being complemented by advisers with expertise in the other vital aspects is normal good practice. A seasoned finance director is comfortable calling in tax experts to augment their mature and established role, rather than fear that it would be putatively undermined.

A legal ops professional may be more or less qualified in one aspect or another, so being complemented by advisers with expertise in the other vital aspects is normal good practice.

The cliché that “lawyers only buy from other lawyers” has some abiding truth such that expert credibility often rests on the precedent legal experience of individuals, much as legal judgment relies on jurisprudential precedent.

Advising a senior GC that they should reorganize their department or review their law firm relationships carries more weight if the adviser has run and reorganized large legal departments as GC, controlled hundreds of millions of dollars of law firm budgets, or run law firms, regardless of what the objective, technical data might show.

A popular example of this is a peer-to-peer GC workshop where individual issues are shared, commonalities discovered, and practical solution paths designed.

There are surprisingly few GCs who do not believe that their department, role, or company is somehow unique. So being able to see that there is nothing-to-very little that is “new under the sun,” through the experiences of those who have sat in many comparable seats to their own, helps broaden their perspective and accept challenging analytical findings and improvement advice more readily.

Taken together, the best consultants should boost the credibility and capability of legal ops professionals and be capable of holding peer-level conversations with their GCs.

“… then our staff will be offended and/or worry about their job security.”

It would be ignoring basic human nature to think that some form of detailed assessment does not give rise to some corresponding degree of anxiety, except among the supremely confident, indifferent, or oblivious.

Viewing performance improvement positively will often be difficult for those who naturally fear change or unfair judgments on their own performance and the validity of such sincerely held hesitancy should not be discounted. This is why ownership of an improvement process is strongly emphasized. Between the two stakeholders of the business and the law, sits the business lawyer as the vital, pivotal stakeholder.

Therefore, each lawyer has the opportunity, nay, obligation to define their mission then to analyze and improve its accomplishment, instead of less-qualified, relatively indifferent departments (whether established in 1915 or otherwise) doing it to them. Unfair judgments might then be avoided, and eventual change focused on the opportunity of filling the glass to more than half full rather than the perceived “threat” of a half-empty measurement.

The current “Great Resignation” shows that a great number of people are willing to instigate major personal change if their organizations are unwilling to explore comparatively minor professional ones.

Bearing in mind this optimistic perspective of potential upsides, offense or worry are not the only typical reactions. There are also many staff who can already identify scope for improvement today – for both business and legal function – and are frustrated at the legal department’s inertia in addressing these opportunities.

The current “Great Resignation” shows that a great number of people are willing to instigate major personal change if their organizations are unwilling to explore comparatively minor professional ones.

“… then other departments will think there are major issues in our department.”

A benchmarking assessment might well objectively and independently confirm the function to be a top performer, corroborating anecdotal, subjective views. Modern business functions are not run on selective impressions and intermittent feedback, however positive, and so the message to other departments is the universal maxim of operational excellence:

If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.