Thirty years ago, I had the privilege of witnessing a live national television broadcast from behind the camera. The opportunity came by happenstance. John Streeter, a friend of mine, and I had just finished playing 18 holes at the Hains Point golf course in Washington DC. While we sat outside on the clubhouse patio enjoying a couple of beers and the warm summer evening, John mentioned that he was in no hurry to go home because his wife was at work. When I asked what his wife did, he explained that she was a technician for ABC in their Washington bureau. That evening she was scheduled to run the control room for Ted Koppel’s Nightline.

When I mentioned that I was a long-time fan of the show, John asked me if I was interested in watching it that evening from the control room. He explained that he would be happy to call his wife to ask her if it would be okay for me to visit the studio and watch the broadcast. I said “yes,” he made the call, and moments later I was in my car heading downtown to the ABC television studios.

When I arrived, John’s wife got me through security, gave me a quick tour of the studio and, to my astonishment, pulled up a stool for me to sit right behind the camera, just a few feet from Ted Koppel. I was fascinated by the whole experience, but one of the more interesting things I observed is that just 60 seconds before going on the air, Ted sat down at an anchor desk that had an assortment of equipment, crumpled papers and other rather non-telegenic items, and smoked a cigarette. With seconds to go before being broadcast nationwide, Ted nonchalantly tossed all of the items from the desk on the floor behind him, crushed out his cigarette and waived the smoke away. As the last wafts of smoke cleared, he looked steadily into the camera and uttered his usual greeting: “Good evening. I’m Ted Koppel, and this is Nightline.”

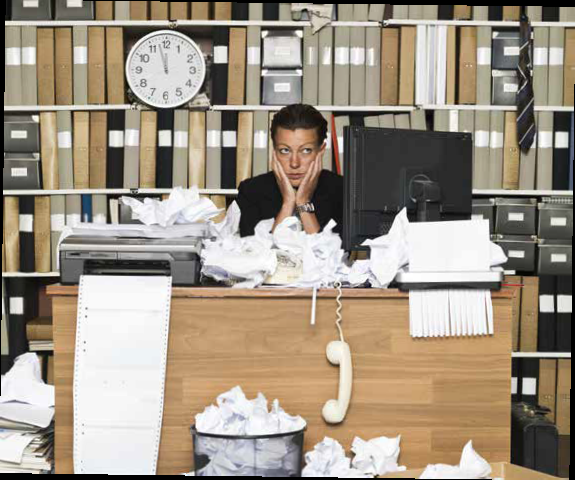

For the viewing audience, the mess behind the desk and the smell of cigarette smoke did not exist. What appeared to the viewers as a neat and well-organized news room, was anything but that. This, I observed, is the magic of television.

I think we all play the same trick to a greater or lesser degree in the way we conduct ourselves at work and in our personal lives. We all have our strengths and weaknesses, and we strive to put on the best show we can while we keep our faults hidden behind the “anchor desk.” I don’t think there is anything particularly wrong about taking this approach. Still, we should not forget to undertake the difficult work of tending to the “messes behind our desks.” The reason for this is simple; unlike television, our ability to mask our character flaws is not perfect and sooner or later, whether we like it or not, they manifest themselves “on camera” for all to see.

Tending to the mess is a lot easier said than done, and the first step — really taking a hard look at and acknowledging our own weaknesses — may be the hardest. Self-reflection is an essential part of this exercise. However, I think it is also important to seek the help of others by reaching out to those who know us best with a genuine request for honest feedback. For our ego’s sake, I think we all tend to view ourselves with a more benevolent and forgiving eye than others do. As a consequence, it is often more difficult for us to see our own character faults than it is for those who know us best.

Several years ago, I participated in a nine-month leadership course that began with an extensive 360-degree review that included a short questionnaire and face-to-face interviews with my colleagues at work as well as my parents, siblings, spouse and children. In this exercise, each of the participants were asked to respond to such provocative questions as “What are people up against when they are with me?” I can say from personal experience that this type of interaction is not for the faint-of-heart. I can also say that if you have the courage to both invite and accept such feedback with no defensiveness and a genuine curiosity to learn more about yourself, you are likely to gain invaluable insights into both your strengths and important opportunities for improvement. I think such a process works best when it is structured and guided by leadership experts, but there is no reason not to initiate such conversations on your own instead of waiting for the opportunity to participate in a leadership program.

I’ll never forget the conversation I had with my mother as part of this 360-degree process. She had provided written responses to the six questions comprising the evaluation, but kept on dodging the one-on-one feedback session. When I did eventually get her on the telephone to talk, she began our conversation by explaining that she needed to get some bread from the oven and asked whether it would take longer than 15 minutes. I said, let’s get started and see. Ninety minutes later, we both agreed that it was the most important conversation we had ever had. It not only provided me with a great perspective on her perception of me, it also served to bring us closer together and created a bond that continues to strengthen to this day.

Of course, once you receive feedback from those who know you best, your work has just begun. The next step is to reflect on what you’ve learned and make use of your new insights to begin the task of cleaning up the mess behind your desk. In so doing, I think it is vital to look for opportunities both large and small to change or alter habits and to strive to achieve a greater capacity for self-regulation in the face of life’s challenges with the object of realizing our potential as authentic, ethical leaders.