American bank robber Willie Sutton famously explained that he robbed banks “because that’s where the money is.” Given Sutton’s compelling logic, perhaps we should not be surprised that the latest banking scandal to come to light involves manipulation of the global foreign exchange markets where an astonishing $5.3 trillion is traded daily.

Each new revelation of corruption in the banking industry becomes more difficult to understand in an atmosphere of extraordinary regulatory scrutiny and vastly increased internal controls. It was recently reported that one in 10 employees of many of our largest financial institutions is dedicated to performing a compliance function. And yet the scandals, with their subsequent-multibillion-dollar fines and government enforcement actions, continue unabated. Before exploring what might be at the root of this pernicious problem in the banking industry, and its implication for corporate governance in general, let’s take a minute to recap the most recent scandal and where it fits in a decades-long pattern of behavior.

On November 12, 2014, HSBC Holdings, Royal Bank of Scotland, SBS, Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase agreed to pay a total of about $4.25 billion to US, British and Swiss regulators to resolve allegations that they tried to manipulate the vast foreign-exchange market. Specifically, traders at these institutions were caught colluding to influence foreign exchange benchmark rates for their own advantage. To do so, they used exclusive chat rooms where traders from two or more banks would communicate to coordinate their trades.

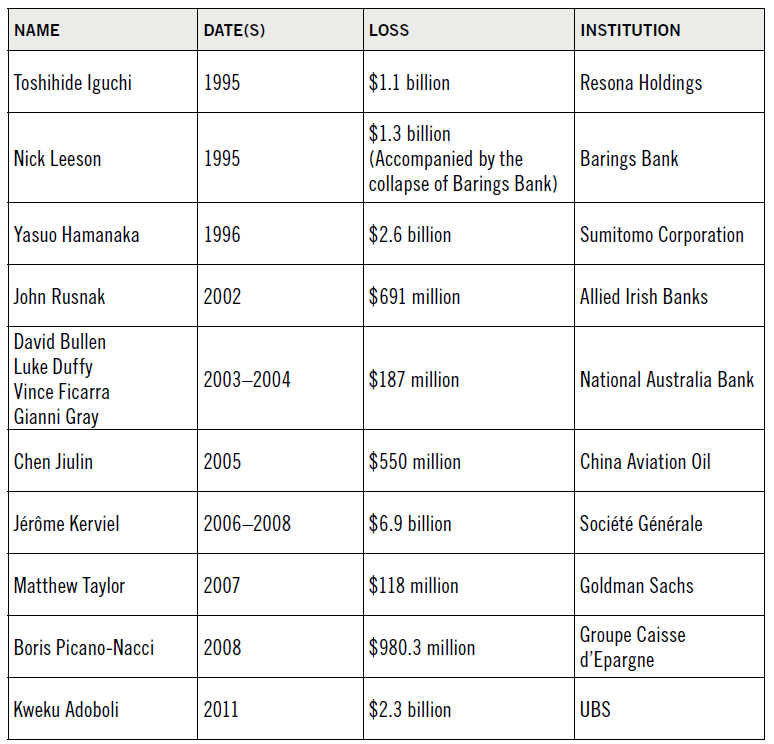

This, of course, is not the first time banks have paid a heavy price for rogue traders. In 2012, the trader known as the London Whale lost at least $6.2 billion for JPMorgan Chase & Co. That same year, it was discovered that traders at major banks — particularly Barclays, UBS, Rabobank and the Royal Bank of Scotland — had been manipulating the London Interbank Offer Rate for their own benefit since at least 1991, resulting in $6 billion in fines. And these are just the latest in a long history of banks paying a heavy price for poor regulation of their traders. On the next page you’ll find a short list of some of the most notorious rogue traders and the punishing losses associated with their exploits.

The point is that rogue trading is a well-understood risk in the banking industry and one that both banks and regulators have spent significant resources to detect and prevent. And yet, such criminal activities persist in one of the world’s most highly regulated industries, operating under extraordinary government scrutiny with massive investments in improved internal controls. Why? How could this continue to happen — especially in the current, hyper-vigilant regulatory environment? These are important questions not just for the banking industry, but for all businesses intent on avoiding the same fate.

There is no such thing as perfect controls because those with a desire to do so will continue to find ways around them.

I draw two conclusions from this persistent scourge that has gravely damaged the reputation of a great industry that plays a vital role in fueling our global economy and in our personal lives. The first is that it is not possible to “control” your way to compliance. As the banking industry has found, there is no such thing as perfect controls because those with a desire to do so will continue to find ways around them.

The second conclusion is that the persistent compliance issues in the banking industry are rooted in a culture that focuses far more on maximizing profits than on the well-being of their customers or other stakeholders as the 2012 New York Times op-ed penned by former Goldman Sachs executive Greg Smith described.

“[T]he interests of the client continue to be sidelined in the way the firm operates and thinks about making money,” Smith wrote on his piece, which gave the world a rare glimpse behind the curtain when he explained why he left the bank:

“I attend derivatives sales meetings where not one single minute is spent asking questions about how we can help clients,” Smith elaborated. “It’s purely about how we can make the most possible money off of them. If you were an alien from Mars and sat in on one of these meetings, you would believe that a client’s success or progress was not part of the thought process at all.”

It is precisely this kind of culture that has likely wrought such havoc on the banking industry for so long and has the potential of doing the same in any firm harboring similar attitudes. It is a classic priority inversion, where the desire to maximize short-term profits is put ahead of doing what is best for the customer and other key stakeholders. The consequences of such a priority inversion are the same regardless of the industry — reputational damage, loss of trust, adverse regulatory actions and likely employee dissatisfaction and unrest.

There is a long list of steps that might be taken to reverse such a priority inversion in a corporate culture. These might include aligning employee performance metrics with company standards of conduct and revising hiring practices to include an emphasis on screening candidates for high levels of integrity. But by far the most potent means of driving a culture to get its priorities straight is focusing on fostering the following five key attributes at every level of company leadership:

- a genuine belief that the interests of customers and other stakeholders are a higher priority than maximizing short-term gains;

- a genuine passion for promoting the well-being of key stakeholders;

- the character strength to choose to put the well-being of key stakeholders above short-term gains even when doing so is difficult;

- a habit of making such choices; and

- the organizational savvy and drive to find a way to get those in their sphere of influence to exhibit the first four attributes.

I’ll grant you that achieving this goal is a tall order in many firms and that it may be exceedingly difficult for the banking industry, given its historic myopic focus on money. However, I believe the vast majority of business professions, both in and out of the banking industry, have high standards of professional integrity and are thirsting for leaders with these five attributes. Taking deliberate steps to unleash this latent desire to pursue the greater good is far more likely to succeed in stemming the tide of corporate corruption than yet another layer of internal controls.