CHEAT SHEET

- BAHA effects. Recent changes to US Immigration policy like the Buy American Hire American (BAHA) Executive Order mean large increases in Requests for Evidence and visa dentals and limitations.

- H-1B program. Intense scrutiny on the H-1B program has caused instability for companies that employ H-1B workers, especially staffing companies in the tech and biomedical sectors and startups founded by foreign nationals.

- L-1A employees. New rules being applied to the L-1A employees could impact whether foreign nationals will be able to hold executive positions.

- File it. Employers should properly maintain Public Access Files and personnel information for all foreign national employees, especially documenting that job titles and duties are in line with visa requirements.

For many general counsel, there are few areas of the law that are more mystifying than immigration law.

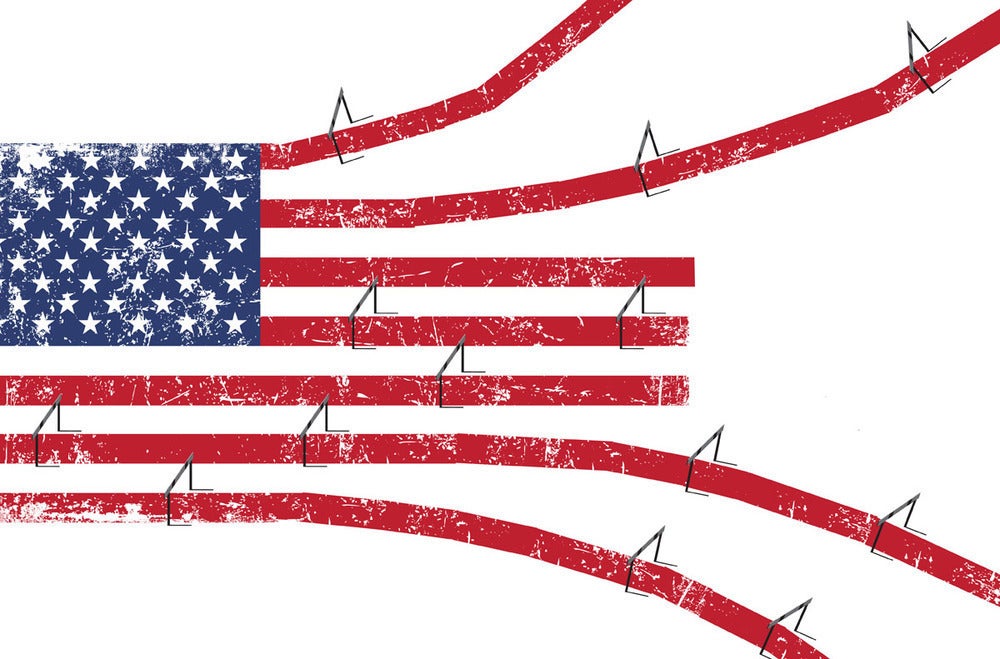

Yet, as we have seen in recent years, changes in federal immigration policy and enforcement can have a significant impact on a company’s available labor force, reputation, and even financial performance. Add in the speed and magnitude of the changes that have occurred in the last few years, and it becomes clear that any US company that uses foreign labor requires legal leaders who understand this shifting landscape. While the state of immigration policy and enforcement is in continual flux, there are a few important trends and changes to keep in mind to mitigate the risk presented by this new era of immigration law, especially regarding H-1B visas and L1 visas.

Last year, during the limited time H-1B adjudication period, nearly 40,000 RFEs (Request for Evidence) were issued to petitioning employers. This over 100 percent increase in RFEs has resulted in significant instability for companies that rely on even a small number of H-1B workers.

Current state of federal immigration regulations: Nothing is constant but change

From the days of the campaign through the fourth year of the administration, President Trump has advanced an agenda aimed at reducing immigration to the United States. The administration’s high priority on immigration reform can be seen through policy memorandum, executive orders, and formal rulemaking; indeed, the US Department of Homeland Security (USDHS) has implemented over 700 changes to existing immigration law. In its most recently published regulatory agenda, the Trump administration has demonstrated its intent to continue reshaping US immigration law, with proposed rules affecting nearly all of the most highly used employment-based nonimmigrant visa categories, as well as the opportunities of graduating students and dependents to work. In order to ensure a company’s ability to retain and attain foreign workers, in-house lawyers and human resources professionals must be incredibly diligent in adhering to these new requirements. In doing so, they will be well prepared for a potential knock on the door from federal immigration enforcement agencies.

Raising the bar: Getting USCIS petitions approved

Recent rulemaking changes, such as the Buy American Hire American Executive Order (BAHA), have resulted in a large increase in Requests for Evidence (RFE) rates and denial rates for petitions in the most common visa categories, as well as in more formal rulemaking to limit the application of those same visa classes.

Targeting H-1B

There is no more scrutinized or controversial immigrant labor program in the United States today than the H-1B program, which (accurately or inaccurately) has long had the reputation as being used (or exploited) by companies as means of procuring lower cost labor and undercutting American workers’ wages and job opportunities. BAHA specifically targeted this program. Last year, during the limited time H-1B adjudication period, nearly 40,000 RFEs were issued to petitioning employers. This over 100 percent increase in RFEs has resulted in significant instability for companies that rely on even a small number of H-1B workers. These additional burdens come in the form of costs in responding, increased stress and uncertainty for employers and employees, and heightened chaos and instability for companies that have already recruited, vetted, and hired workers. These effects have been felt most acutely by certain industry segments, most notably staffing companies (primarily in the tech or biomedical sector) and startups (especially those founded by foreign nationals), which have been specifically targeted by USCIS.

Certain requirements have been relied upon heavily by USCIS to deny H-1B petitions:

- Insufficient efforts to recruit Americans prior to filing;

- Inadequate hiring standards or job descriptions establishing positions as “specialty occupations”;

- Pay levels too low to qualify as “specialty occupations” or “professional”;

- Insufficient demonstration of “hiring and firing” authority, especially where the beneficiary of a petition has the ability to hire or fire within the organization and no board supervision exists; and

- A more restrictive definition of the term “employer-employee relationship,” making it more challenging to acquire an H-1B approval for employers with beneficiary employees working offsite.

New pressures for L-1

USCIS has also recently promulgated a rule that would carry the same concepts from the H-1B program to L-1 employees. Historically, a significant number of L-1A executives were the chief executive of either the foreign or US entity, often opening a new office in the United States. Now, in attempting to carry the definition of “employer-employee” forward to match the H-1B definition, there is a question as to whether foreign employees will be able to sit near the top of the organizational pyramid, often a key component of the structure of foreign companies opening affiliated offices in the United States.

Further, it’s now clear that USCIS wants to formalize a “minimum wage” for L-1A employees well in excess of what is required by federal or state law. As you can imagine, employees who have been working in smaller economies and are now being sent to work for an affiliated company in the United States often have salaries more closely aligned to their colleagues back home than the US labor force. For a visa category predicated on knowledge of a global brand and global products and services, the application of protectionist labor standards is inconsistent. Along those same lines, USCIS is asking to significantly narrow the definition of “specialized knowledge,” meaning those persons with proprietary knowledge of the products and services of a foreign company hoping to do business in the United States may no longer be able to come, even if to train United States workers in an effort to grow the business domestically. With the natural time limitations on this visa classification of five years, many economists do not see the reason for protectionism of this nature — by definition, the companies intend to return the labor home within that five-year period, likely leaving permanent US labor in place thereafter. Nevertheless, that is the rule expected to take effect later in 2020. Employers need to be aware of this.

Rise of enforcement: Site visits and stricter scrutiny

The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), tasked with adjudicating all employment-based visa petitions filed in the United States, has a nearly US$4 billion budget and has reallocated funding to dramatically increase enforcement. The USCIS Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate (FDNS), is tasked with “safeguarding the integrity of the lawful immigration system.” FDNS operationalizes that mission through unannounced site visits to employers of H-1B and L-1 visa holders through its “Targeted Site Visit and Verification Program.” During these site visits, FDNS officers verify that the employee is working in accordance with the specific terms of the immigration petition approved for that worker. After the site visit, FDNS will issue its findings and, if it believes that the labor being performed by the foreign national is not in strict accordance with the approved petition, it will file a “Notice of Intent to Revoke” the worker’s approved petition. Once this notice is issued, it’s difficult and expensive to fight, and the employer often feels they have no choice but to terminate the worker’s employment.

After the site visit, FDNS will issue its findings and, if it believes that the labor being performed by the foreign national is not in strict accordance with the approved petition, it will file a “Notice of Intent to Revoke” the worker’s approved petition.

Whether it relates to the cost of defending such a visit or the resultant notice, the potential interruption to productivity, or even the effect on the morale and comfort levels of high-level employees, many companies have found such visits incredibly disruptive. The risk of such visits can result in an employer taking a conservative approach to the employment of foreign nationals. For example, a company may try to reduce the risk of a notice by placing significant limitations on promotions and job growth for the workers, isolating them within the organizational structure, and maintaining job titles or duties even when there is a business case to change them, all the express purpose of passing an FDNS site visit.

Immigration terms for dummies

REQUEST FOR EVIDENCE (RFE)

A request by the reviewing agency for more information to support an immigrant/non-immigrant application for immigration benefits. In previous years, this was an infrequent response from USCIS, which generally was issued to poorly documented applications or cases where the applicant’s eligibility for the benefits was unclear. The current administration, whether through more restrictive policies or to “kick the can down the road” due to dramatically reduced staffing levels, has begun to frequently issue RFEs, even when petitioners have clearly met the regulatory and documentary standard. RFEs can require the amassing of huge numbers of documents, often in a short time period, and create a heavy administration and financial burden for companies.

H-1B VISA: A visa available to professionals in positions that require the specific university degree that the visa beneficiary possesses (limited to roughly 68,500 new beneficiaries per government fiscal year).

H2A AND H2B PROGRAM: Permits companies to hire seasonal, one-time, or peak-load level employees in the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors, respectively.

L-1A VISA: Allows companies to transfer supervisory, managerial, or executive employees from a concerned affiliate going abroad to similarly supervisory, managerial, or executive roles in the United States. Maximum duration is seven years.

L-1B: Allows multinational companies to transfer employees who possess “specialized knowledge,” often of a company’s products, services, or processes, from an affiliated foreign office to a US office. Maximum duration is five years.

OPT/CPT: Optional/Clinical Practical Training available to recent graduates of US universities. OPT is initially a one-year grant of employment authorization, which can be extended to 39 months for STEM (Science/Technology/Engineering/Mathematics).

Adding to the confusion, there is another agency that has responsibility for some work-related visa enforcement, which has also been stepping up enforcement activity in recent years. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has responsibility for enforcing and maintaining Optional Practical Training or Clinical Practical Training (OPT/CPT) programs for university students seeking post-graduate on-the-job training for between 39 months (non-STEM) to 66 months (for STEM graduates). These programs, while largely administered and monitored by school officials, do require employers to demonstrate and document that the student is being employed pursuant to an approved training program.

They may also require that the employer use the E-Verify employment verification program. Student enforcement visits (nearly identical in format to FNS site visits) have nearly doubled in the past 18 months. These visits generally demand full and complete sets of training programs, USCIS and DOS filings (often provided by the school at the time of hire), completed I-9s, paystubs that meet all requirements (including limitations on payroll taxes paid by OPT/CPT students), and proof of working more than 20 hours per week at the pay level initially offered. Employers, unsurprisingly, sometimes fail in their recordkeeping responsibilities, with unfortunate results for workers and employers. This failure can have lasting effects on an organization — employers have anecdotally reported a direct correlation between a determination of noncompliance on an ICE student visit one year and an FDNS site visit within the following year.

Best practices for in-house counsel

- Stay informed. Maintain dialogue with both immigration counsel and leadership within their companies.

- Start early. In some cases, moving employees to an early pursuit of a green card may be recommended, especially as green card standards are, in some cases, more achievable than in visa petitions.

- Be honest. In light of the new timelines and standards, be realistic about what can be expected from USCIS and how long an employee can reasonably be employed.

- Have a backup plan. Having a plan that reaches beyond the foreign employee to ensure a transition should that employee lose her ability to serve in her proffered position is now a necessary evil that cannot be ignored

- Document any challenges faced in recruiting available US labor, the specific educational accomplishments (in the case of H-1B employees) or proprietary knowledge or experience of its L-1 beneficiaries, and that the requirements the company has put in place with regard to those employees are consistent with those which apply and have previously applied to its US labor.

- Ensure that the supervisor of all foreign employees has a plan for the duties to be performed by the foreign national and the deliverables the company can expect from her in the petition period is also useful.

- If you have employees with work authorization through Employment Authorization Documents (EAD), make sure that those employees apply for renewal at the earliest possible date (usually 120 days before expiration). This is especially important now, when EAD issuance is delayed to an all-time level, sometimes more than six months

- Finally, for H-1Bs specifically, obtain expert opinions on the need for a specific educational path to successfully fulfill the requirements of a position, including identifying specific coursework that enables the foreign national to carry out her duties, can be invaluable.

- Speak out. This is a time of tremendous change and the business community has always had an important voice in the conversation. If you have challenges or want to see changes to the laws, advocate for them through various organizations.

It also risks denial of the OPT/CPT employee’s work authorization without warning. Both as a result of stepped-up enforcement and of the government’s dismissal of decisions made by colleges and universities, there is now more consistent revocation and denial of practical training EADs, often resulting in immediate loss of status and the ability to work. In its 2019 report of future action, USDHS promises a “comprehensive reform” of the practical training programs, and nearly everyone expects further restrictions on the availability of recent foreign graduates, all the while we continue to see significant lowering of rates of US students in many STEM fields.

What can an employer do?

- Properly maintain Public Access Files and other personnel files for all foreign national employees. This is of paramount importance and is the first step to compliance.

- Have in-house counsel work with human resources staff to ensure I-9 compliance (or conduct a full audit/review when joining a new company to ensure compliance).

- Work with payroll providers to ensure that they understand the unique tax classifications for such employees.

- Train supervisors of foreign labor to ensure compliance in job duties and titles.

- Train “gatekeeper” staff to ensure accurate communication with potential site visitors. FDNS officers may call first, simply turn up, or even conduct a brief interview with reception staff on the phone or in person before anyone else in the building knows they are there. If your foreign employee has maintained a different title in the workplace or works from a remote location or even from home, the information provided by reception staff can result in a Notice of Intent to Revoke without any further investigation, resulting in lasting ramifications for both employer and employee.

- Stay informed. Ask your immigration counsel to keep up with changes to the frequency, content, and trends within site visits generally.

- Maintain personnel files that meet the clear requirements of USCIS, ensuring that job titles and duties do not stray far, if at all, from the company’s underlying USCIS and Department of Labor filings.

- Monitor foreign labor. Employers must be diligent about filing amended petitions when worksite location, job duties, position in the organizational chart, or other material changes to employment occur can help reduce the risk to the company.

Along with the changes to the L-1A program and reform of the OPT/CPT program, USDHS has been clear that it also intends to eliminate work authorization for H-4 spouses of H-1B professionals from India and China. This is significant not just in terms of raw numbers (it is believed more than 100,000 educated spouses to primary green card beneficiaries rely on this plan now and are employed in high wage jobs), but also as it affects the H-1B beneficiary who may work inside your company. If your employee’s spouse, also in the midst of a professional career, suddenly loses the right to work, it may well impact the decision the employee makes in terms of remaining in the United States or returning home or to a more favorable jurisdiction.

Train “gatekeeper” staff to ensure accurate communication with potential site visitors. FDNS officers may call first, simply turn up, or even conduct a brief interview with reception staff on the phone or in person before anyone else in the building knows they are there.

It is apparent that USCIS and the Trump administration do not intend to expand the availability of foreign labor and, in its plan for 2020 and beyond, it’s plainly speaking about its belief that many foreign employees could be replaced by US labor. As a result of this, Congressional inertia on the topic, and the Buy American Hire American Executive Order signed by the President on April 28, 2017, it’s hard to envision more permissive immigration policies in either the short term.

ACC EXTRAS ON… Immigration law

ACC Docket

Avoiding Employment Litigation: A Guide for Multinational Companies (May 2019).

The Latest Updates on H-1B Visa Sponsorship (Oct. 2018).

Primer

The International Comparative Legal Guide to Corporate Immigration 2018, 5th Edition (Aug. 2018).