CHEAT SHEET

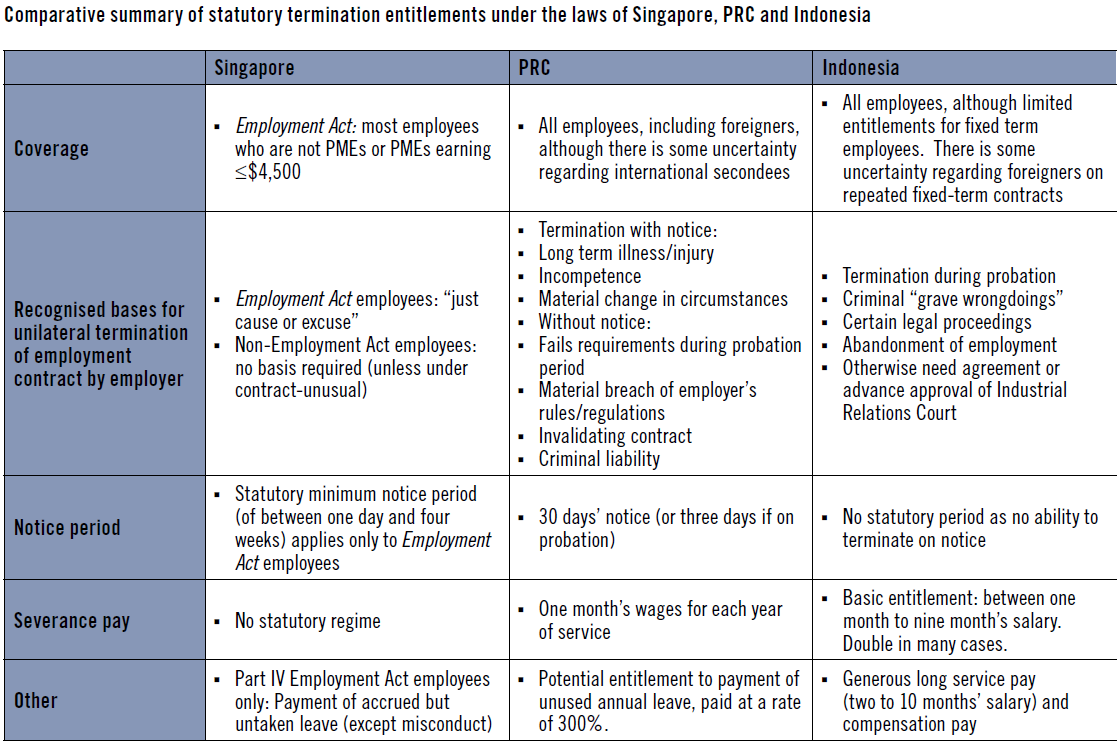

- Coverage of statutory termination entitlements. Recent amendments to the Singapore Employment Law have extended general provisions to professionals, managers and executives. The PRC and Indonesian frameworks also apply to all employees, with limited exceptions.

- Unilateral termination of employment contract by employer. Under the Singapore Employment Act, an employee can seek reinstatement or compensation on the basis of alleged dismissal “without just cause or excuse.” The bases for termination in PRC and Indonesia are more restrictive.

- Severance pay. There is no statutory entitlement to severance pay under Singaporean law. In both PRC and Indonesia, an employee is typically entitled to basic severance pay.

- Other statutory termination payments. Under Singaporean law if any employee’s employment is terminated for misconduct then he or she is not entitled to a payout of accrued leave. In PRC, an employee is normally entitled to payment of accrued but untaken leave. Under Indonesian law, employees are entitled to long service pay and compensation pay.

The diversity of employment law regimes across Asia presents a challenge to multinational companies that operate within the region, and their personnel responsible for managing the regional workforce. Singapore generally provides limited regulation of employment. By contrast, Indonesia heavily regulates employment contracts, while the People’s Republic of China (PRC) sits somewhere in between.

In this article we compare the statutory regimes in Singapore, PRC and Indonesia, with respect to termination entitlements and claims. This comparison shows that, despite recent amendments to the Singapore Employment Act, Singapore remains an employer-friendly jurisdiction, when compared to other Asian jurisdictions; there is a smaller body of employment law, and a more contract-focussed approach, than in many other locations regionally or globally.

Statutory termination entitlements

Coverage of statutory termination entitlements

Historically, the Singapore Employment Act applied to most employees, but for the most part its provisions did not apply to those “employed in a managerial or executive position,” sometimes referred to as “professionals, managers and executives” (PMEs). However, recent amendments to the Employment Act (which came into force April 1, 2014) have extended its general provisions to PMEs earning a monthly salary of SGD 4,500 or less. These PMEs now have access to basic entitlements under the Employment Act, including the ability to seek relief for unfair dismissal. Access to unfair dismissal relief is, however, limited to PMEs who have been employed for at least 12 months, except in the case of summary dismissal (in which case the 12 month requirement does not apply).*

* Summary dismissal means dismissal without a period of notice, e.g., in cases of serious misconduct.

The PRC and Indonesian frameworks also apply to all employees, with limited exceptions (as shown in the table at the end of this section).

Recognised bases for unilateral termination of employment contract by employer

Under the Singapore Employment Act, an employee can seek reinstatement or compensation on the basis of alleged dismissal (including termination on notice) “without just cause or excuse.” The employment of non-Employment Act employees can be terminated without reason, provided this is consistent with the employment contract. Normally, the contract will allow either party to terminate without cause by the provision of a period of notice of termination.

The bases for termination in PRC and Indonesia are more restrictive, making unilateral termination more difficult. In PRC, the basis on which employment can be terminated depends on whether or not that termination is effected on notice (or payment of wages in lieu of notice). Termination can be effected on notice if the following occurs:

- the employee is unable to resume work after a long term illness or injury;

- the employee is incompetent and remains incompetent after training or adjustment of his or her role; or

- there is a material change in the circumstances, making continued performance of the contract impossible.

Termination can be effected without notice for a number of reasons, including if the employee does the following:

- fails to fulfill requirements of the employment during the probation period;

- materially breaches the employer’s rules and regulations;

- causes the labour contract to be invalid (e.g., if the labour contract was entered into fraudulently); or

- is subject to criminal liability.

In Indonesia, unilateral termination is even more difficult. Generally, termination must be by agreement with the employee or with prior approval of the Industrial Relations Court (IRC). Such approval is required for termination (absent agreement of the employee) where the employee:

- has committed “grave wrongdoings”;

- has breached the employment contract, for which three prior written notices are required; or

- is ill or disabled for 12 consecutive months.

The prior approval of the IRC is not required for termination in the following cases:

- during a probation period;

- where an employee is detained for criminal conduct;

- if the employee is absent due to certain legal proceedings; or

- abandonment of employment (which is where an employee is absent from work for five consecutive days without a valid reason).

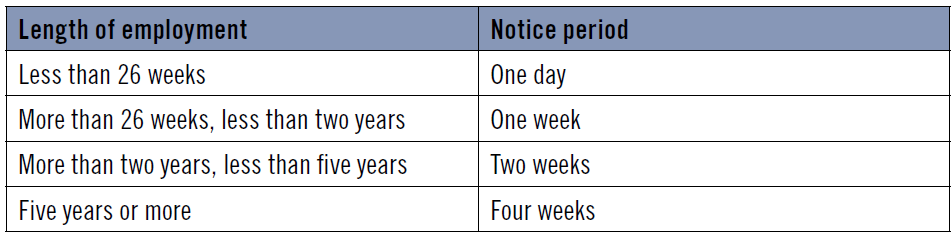

Notice period

For employees covered by the Singapore Employment Act, the minimum notice period depends on the length of employment, as shown in the below table.

In the PRC, the minimum statutory notice period is 30 days (or three days if the employee is still within the probation period).

Under Indonesian law, there is no notice period as there is no ability to terminate on notice; termination (that is not by agreement) usually requires the approval of the IRC and, where IRC approval is not required, there is no need to give notice. As there is no statutory notice period, a provision in the employment contract that permits an employer to terminate the contract without cause by giving notice will be invalid and unenforceable.

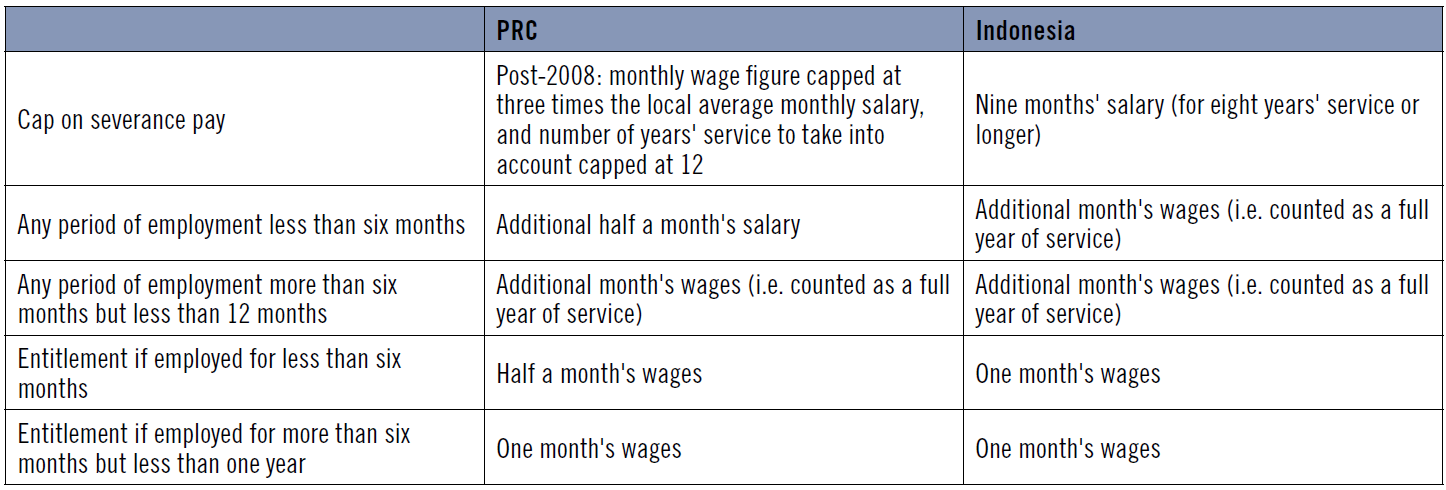

Severance pay

There is no statutory entitlement to severance pay under Singaporean law, although such a claim could potentially be made under industrial relations laws. However, in practice, many employers do provide severance payments on retrenchment (termination by reason of redundancy or reorganisation of the workforce), which often correlate with the employees’ length of service. This is consistent with the “Tripartite Guidelines on Managing Excess Manpower” published by the relevant tripartite body comprising the Ministry of Manpower, unions and employer bodies.

In both PRC and Indonesia, an employee is typically entitled to basic severance pay (not only in case of redundancy) of one month’s pay per year of service or thereabouts. There are some differences, which are summarised in the below table.

The basic severance pay referred to above is often doubled under Indonesian law, depending on the circumstances of termination.

Other statutory termination payments

While there is no statutory severance pay regime under Singaporean law, employees covered by Part IV of the Employment Act are entitled to payment of accrued but untaken leave (other employees do not have a statutory entitlement to annual leave). If any employee’s employment is terminated for misconduct then he or she is not entitled to a pay-out of accrued leave. Employment contracts for employees generally often reflect these statutory provisions.

Under the recent amendments to the Employment Act, the scope of Part IV has been extended. Employees who earn SGD2,500 or less per month in ordinary remuneration are now covered by its provisions. Previously, Part IV only applied to the following:

- employees earning SGD2,000 or less per month in ordinary remuneration; and

- “workmen” (those workers engaged in manual labour or heavy operational work) earning no more than SGD4,500 per month (this threshold was unaffected by the recent amendments).

In PRC, in addition to severance pay, an employee might be entitled to payment of unused annual leave, in which case such leave is paid at a rate of 300 percent.* However, if a termination is scheduled then it is common practice for the employer to grant, and for the employee to take, any unused annual leave before the scheduled termination date, paying the employee his or her normal salary. This means the employer does not need to pay compensation for unused annual leave.

* This means that for each day of unused annual leave the employee is paid three times his daily salary. So if an employee is paid $100 a day that employee will be paid $300 for each day of unused annual leave.

Under Indonesian law, employees are entitled to the following:

- long service pay, which is between two and 10 months’ salary, also calculated by reference to the employees’ length of service; and

- compensation pay, which includes unused annual leave that has not expired, relocation expenses, and medical and housing allowance.

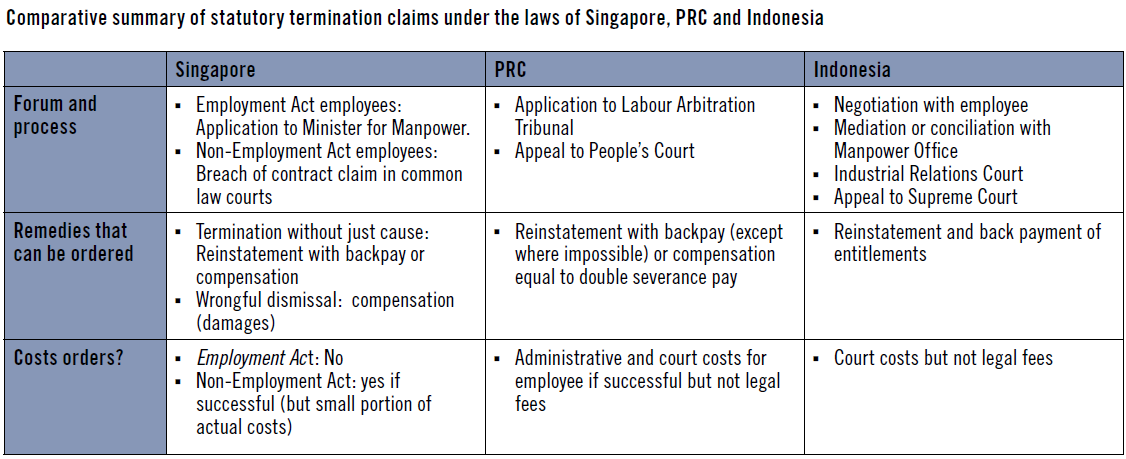

Statutory termination claims

Singapore

Under Singaporean law, the forum and process for a termination claim depends on whether the employee is covered by the Employment Act. Employees who are covered under the Employment Act may make an application to the Ministry of Manpower. Non-Employment Act employees may only pursue an ordinary breach of contract claim through the common law courts, sometimes called a “wrongful dismissal” claim.

In the former case, the employee may seek reinstatement with backpay, or compensation. In practice, there are relatively few claims and the remedies tend to be less than in many other jurisdictions — compensation is not formally capped but, broadly, tends to be in the range of one to three months. Reinstatement is very unusual as a remedy.

An employee wrongfully dismissed may claim compensation (“damages”) only, which is normally limited to the remuneration that would have been earned had the employer observed the prescribed notice period.

Singapore’s unfair dismissal regime is light compared with many other jurisdictions, and there is very little anti-discrimination law. This makes employee terminations less risky than in many other locations. However, there are other avenues employees can pursue — in theory or practice — so thought still needs to be given. For example, a very new Protection from Harassment Act could have potentially broad application (with causes of action against individual managers and, potentially, the employer) including the possibility of “stigma” or psychiatric injury damages from abusive employment. Also, Singapore’s recently introduced privacy law, the Personal Data Protection Act, gives aggrieved employees another avenue of complaint if an employee’s personal information is not adequately protected. The Tripartite Guidelines on Fair Employment Practices, published by the Tripartite Alliance for Fair and Progressive Employment Practices (TAFEP) should also be considered, together with the Fair Consideration Framework, which was recently introduced by the Ministry of Manpower.

While the risks are lower, employers must still consider the practical and legal risks of any termination, and best practices in implementing terminations are still generally advisable.

PRC

In PRC, an aggrieved employee must first lodge an unlawful dismissal application with the Labour Arbitration Tribunal. A decision by the Tribunal can be appealed to the People’s Court.

If an employee is successful, he or she may be reinstated, with backpay. If the employee does not seek reinstatement, or reinstatement is impossible, then the employee will receive compensation, which may be equal to double the employee’s statutory severance pay (see above).

Indonesia

The termination process under Indonesian law is onerous on employers. The employer must attempt to negotiate a termination agreement with the employee or employee’s union. If the parties do not reach agreement then either party may bring the case before the Manpower Office for mediation or conciliation. If the case cannot be settled through these means, then the matter will be referred to the Industrial Relations Court. Either party may appeal from the decision of the Industrial Relations Court to the Supreme Court.

An employee may seek reinstatement and back payment of entitlements as a remedy for unlawful termination.