Many times, it isn’t enough to know the law and your industry well — to clear a full plate, in-house counsel should be skilled in project management.

Antonio Nieto-Rodriguez, project management office head and sustainability transformation program director at GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, is a global leader in his field and author of the Harvard Business Review Project Management Handbook. He spoke with executive coach Amii Barnard-Bahn about his experience.

Working as head of transversal project portfolio management at BNP Paribas Fortis during the 2008 mortgage crisis, “I remember there was so much new regulation and panic in the bank,” Nieto-Rodriguez recalls. Among other regulations, Sarbanes-Oxley had just been passed, and these regulations alone would have consumed an estimated 80 percent of the key projects underway at the bank, he says. Their scope was burgeoning daily.

Fortuitously, an in-house counsel pointed out that the bank could aim for a minimum scope and still be in compliance. “That freed up so much capacity — we appreciated the counsel that came up with the idea of just focus on the matter; don’t try to solve everything,” he says.

In his experience, Nieto-Rodriguez finds that attorneys bring a gift of creativity to project problem-solving. Given that everyone understands the business must keep growing and evolving and that legal is not a revenue-generating function, it is critical to scope legal and regulatory projects carefully. Recognizing that resources are limited, “If you put 50 percent of your budget in regulatory, growth isn’t going to happen.”

Defining a “project”

It's important to distinguish between a “true project” — one with complexity or novelty that requires formal project management — and a “minor or routine project,” which can be carried out following a set of guidelines.

For example, writing an annual report could be seen as a true project yet does not require a project manager. There is an established process and designated responsibilities for annual report creation, and special sponsorship, budget, and novel issues don’t generally arise. True projects involve fresh challenges not faced by the organization previously.

Most organizations attempt to accomplish too many projects. Nieto-Rodriguez jokes he’s come across “projectification” in which organizations have tasked themselves with more projects than employees. “That’s crazy, right?” he says. His observation is that many organizations take on too many projects because they’re easy to launch. “You just need to have an idea and call a kick-off meeting,” he says. Most organizations lack a healthy review process for shutting down projects — and this leads to a glut.

Most senior leaders — despite their critical role — have not learned how to prioritize, cancel, or effectively sponsor projects.

“I always tell leaders that if you’re going to start a new project, make sure you first stop or finish two or three other projects.” Most senior leaders — despite their critical role — have not learned how to prioritize, cancel, or effectively sponsor projects. The good news is there is a solution: Engage project management specialists who can advise leaders in making the difficult calls.

The role of legal in projects

It’s tough these days to think of a major corporate initiative that doesn’t require at least some involvement of in-house counsel — in fact, legal is one of the most demanded resources in many projects (at least 50 percent according to Nieto-Rodriquez). And when legal assistance is in high demand, it can become a bottleneck. As a result, the maturity of in-house counsel regarding project management has grown sharply in the past five to 10 years. “They may not be project management experts, but they do understand their role in projects. They’ve gotten more efficient and effective.”

And why is this so critical? Large organizational projects cost, on average, upwards of US$100,000 in this author’s experience, but the overall failure rate is 65 percent.

The top reasons for failure:

- Executive management not prioritizing, selecting, or effectively sponsoring projects;

- Organizational culture issues such as hierarchies, silos, and authoritarian cultures that are inflexible or resisting the growing norm of agile and fluid styles; and

- Project managers failing to take ownership of project results, and focusing only on deliverables (for example, designing a process that satisfies compliance requirements, but creates negative consequences on organizational sales workflow that could have been anticipated and addressed).

For these reasons, the most successful projects contain dedicated staff who spend 100 percent of their time on them, starting with the project manager and including the main contributing team members.

A helpful evolution is that in-house counsel are increasingly brought in at the beginning of a project, rather than the end. Most of the time legal plays a touch-base type role, to be informed or consulted. As counsel, you can negotiate this upfront, attending the first few meetings until you understand the scope and have a chance to assess risk.

For example, once you get comfortable with the project and trust that the team will keep you informed, you can back off a little bit. Educate team leads on the legal red flags, and explain that when certain milestones are met, you should be invited back to the meetings. Some companies may also use online systems where you are given access to easily track status updates.

Educate team leads on the legal red flags, and explain that when certain milestones are met, you should be invited back to the meetings.

With regard to legal and regulatory projects, they are unique in that: 1) There is usually a fixed deadline, and 2) they are usually not about innovation or growth, and so can be considered dull, which can de-motivate the project team.

You can help excite them: Dig deep, identify, and communicate the higher purpose of the project. For example, if your project is about upgrading a document management system, talk about why you want to improve it. Emphasize how achieving this work will save employee work time and better protect client and employee data. These are more engaging reasons for a project than simply “upgrading a system.”

Another challenge regarding legal and regulatory projects is that they usually increase in scope and size. You start with a new risk that needs to be addressed, thinking it will be a small task to solve. A few days later, it becomes an official project to map out and, in some cases, it morphs into a massive program. Other stakeholders may piggyback their pet projects onto it, taking advantage of the knowledge that the project is often of a mandatory nature. With effective senior management sponsorship, project managers can provide a key gatekeeping function, keeping the scope tight and focusing on the original issue.

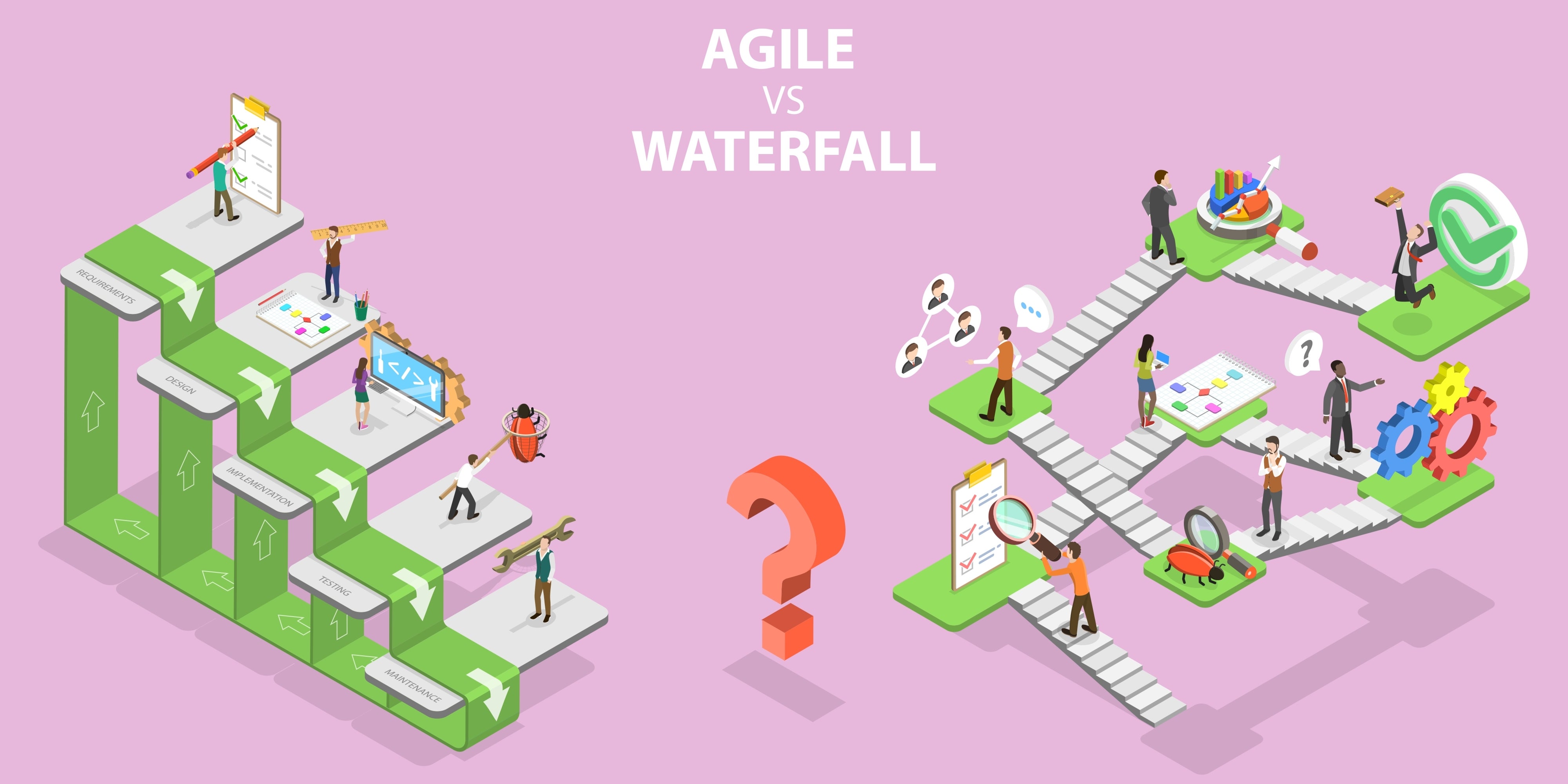

Project management methodology: Waterfall or Agile?

Within project management, there is an ongoing debate — even confrontation at times, between the two major styles of project management — “Waterfall” and “Agile.”

Waterfall methodology is a linear PM approach that progresses in logical steps to advancement. Requirements are clearly defined at the outset. For example, Waterfall PM is similar to buying an empty plot of land, waiting to build the house until you have all the architectural plans in place, and then executing each piece of the project step-by-step.

Agile methodology got its start during the internet boom and increase of information technology in the early 2000s. Using Agile is working right away and iteratively on the deliverables of a project, in what are called “sprints.” Agile breaks a project down into small, consumable increments, measures progress along the way, and makes pivots when necessary.

In our house example above, Agile would start building the kitchen without detailed plans, and could design the critical placement of the “cooking triangle” (sink, refrigerator, and stove) by studying the homeowner’s habits in the actual space — and then begin building. The benefit of Agile is its ability to address issues in real-time and to test and absorb new information quickly to deliver value more rapidly and avoid major customer issues later that may become more ossified and harder to address.

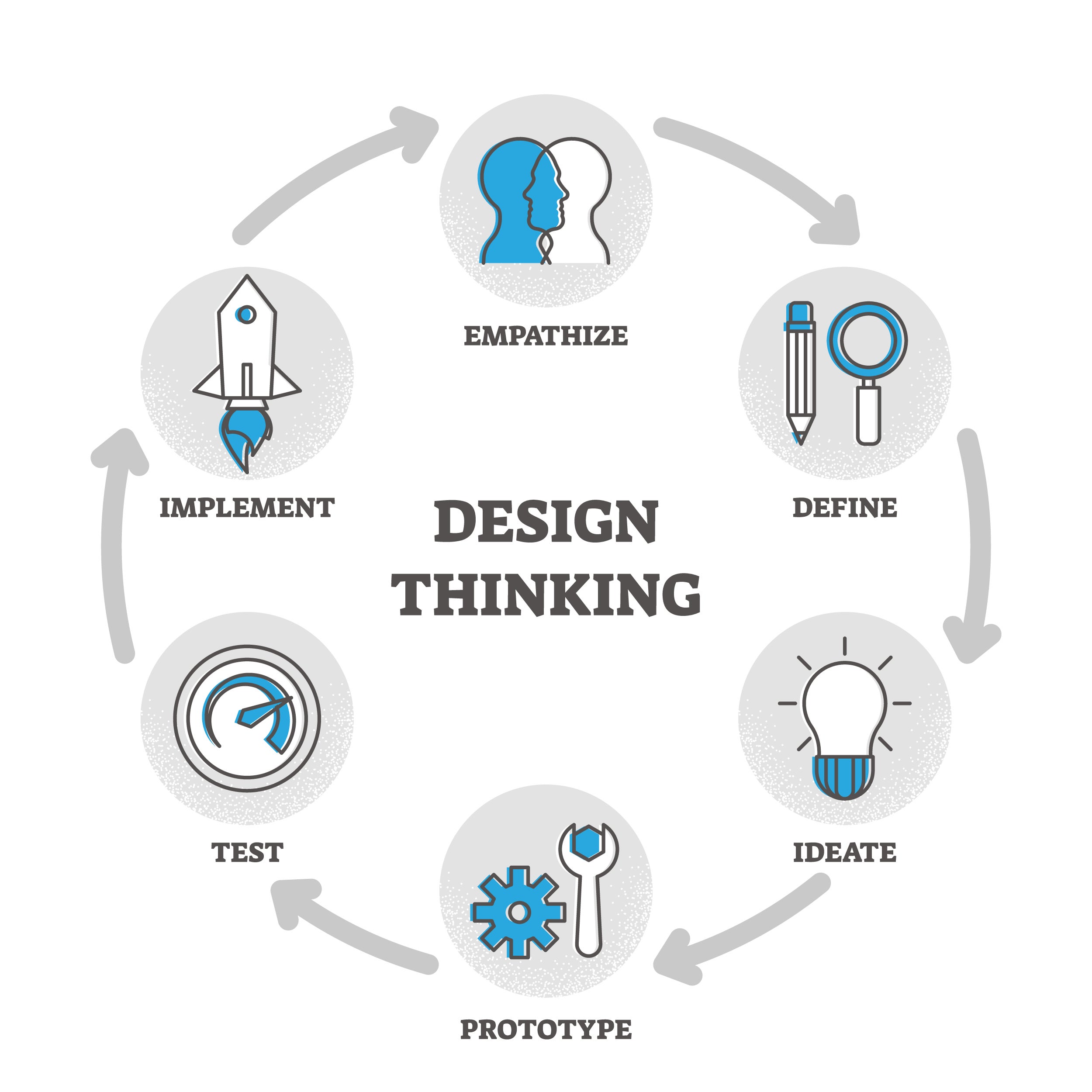

Both approaches to project management provide strengths and benefits, and Nieto-Rodriguez believes they should be considered tools in the toolbox, along with a few others, such as Design Thinking and Six Sigma.

Change is happening so quickly in organizations that a mix of both Agile and Waterfall methodologies is often beneficial. When you have a large traditional project, Waterfall may make more sense because it focuses clearly on outcomes, breaking down time and workload.

If the project is novel and outcomes are not clear (for example, exactly how the company’s existing processes may be developed to comply with a new, evolving regulation), Agile may be a more flexible way to start when requirements are still evolving. Without a defined end goal, Agile can begin work on achieving an initial desired user benefit as a starting place and modify the project in real-time as new information is provided. Customer collaboration and rapid change responsiveness are key hallmarks of Agile.

Use the right tool for the right solution.

Finding a qualified project manager

Project management is arguably one of the most valuable disciplines not taught in graduate school (only two of the top 100 Masters of Business Administration programs in the world teach project management as a core course).

When considering project leadership, a Project Management Professional (PMP) designation, such as from the Project Management Institute, is a solid credential. More recently, there are certifications for legal project management and continuing executive education programs cropping up at universities. You also want to vet whether the person has had experience managing similar projects in the same field.

However, emotional intelligence is even more important than a PM credential. “If you’re not a people person, if you create fear in the team, and just don’t like people, it’s not going to work very well,” warns Nieto-Rodriguez. As with most success, while technical skills are critical, achieving goals always comes down to relationships.