Banner artwork by Dusan Arsenijevic / Shutterstock.com

Cheat Sheet

- Consider the “meaningful limit.” Finding a meaningful limit that overrides the exception is the avenue toward patent eligibility, including integrating the claims into a “practical application.”

- Provide art-based amendments. Amendments to overcome art-based rejections can also overcome rejections for patent eligibility.

- Understand the Deferred Subject Matter Eligibility Response Pilot Program. The pilot offers insight into how the USPTO may change the patent process, while also acknowledging there is room for improvement.

Patent eligibility at the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has been a confusing, and often frustrating topic since the US Supreme Court’s decisions in Mayo and Alice. Certain areas of discovery have been deemed ineligible for patenting due to precedents that have been created over years of court decisions. The judicial exceptions include the areas of abstract ideas, natural phenomena, or laws of nature. For example, one may not patent naturally occurring minerals, gravity, or mathematical equations. The US Supreme Court decision in Mayo, reinforced in Alice, added a complex, multi-prong analysis to determine if these judicial exceptions to patent eligibility apply.

Since its inception, the patent eligibility analysis has had its critics, from current and former US federal circuit judges, to former USPTO commissioners.

Since its inception, the patent eligibility analysis has had its critics, from current and former US federal circuit judges, to former USPTO commissioners. In February 2022, the USPTO introduced a Deferred Subject Matter Eligibility Response (DSMER) Pilot Program to attempt to streamline the analysis.

Rejections because of the judicial exceptions

Under the current analysis for subject matter eligibility (SME) under 35 U.S.C. § 101, a patent claim that is directed to an abstract idea, a natural phenomenon, or a law of nature may be patent eligible if the underlying judicial exception is incorporated into a “practical application”:

A claim that integrates a judicial exception into a practical application will apply, rely on, or use the judicial exception in a manner that imposes a meaningful limit on the judicial exception, such that the claim is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the judicial exception.

USPTO’s Manual of Patent Examining Procedure

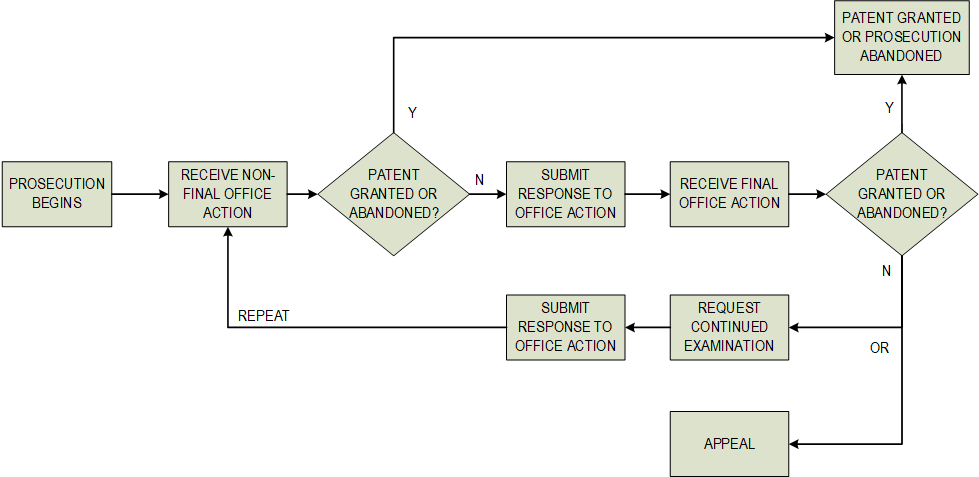

The path to patent eligibility, therefore, often lies in the search for a “meaningful limit” on the concepts recited in the claims. In some cases, the meaningful limit may come about naturally during drafting, filing, and negotiating with the USPTO (known as “patent prosecution” as a whole). The figure below illustrates a simplified view of the patent prosecution process:

The patent prosecution process may include multiple rounds of prosecution in which actions by the USPTO (known as “Office actions”) may either grant a patent or provide a rejection. If the patent hasn’t been granted after a round of prosecution, which typically includes a “non-final” and “final” Office action, a decision must be made by the applicant whether to appeal or continue to negotiate with the USPTO, which begins another round of prosecution.

During responses to Office actions, limiting amendments are added to the claims to overcome prior art references cited as part of a rejection for obviousness (35 U.S.C. § 103) or novelty (35 U.S.C. § 102). As a result, a claim which appears to be directed to a judicial exception by an examiner early in prosecution of the application, may be deemed as having a meaningful limit merely through the application of amendments for non-SME reasons.

Congressional concern

Amendments in response to art-based rejections have the potential to also address SME rejections, which has caught the attention of those looking to clarify eligibility determination. US Senators Thom Tillis and Tom Cotton wrote a letter asking for clarification. In their March 22, 2021 letter, the senators noted that:

Unfortunately, current patent eligibility jurisprudence lacks the clarity, consistency, and objectiveness the other grounds of patentability possess. Our concern is that by conducting an inherently vague and subjective analysis of eligibility early in the examination process, examiners may be spending inordinate time on Section 101 at a time when it is difficult or impossible to conduct a meaningful examination under Section 101, at the expense of the more rigorous analysis and precise and thoughtful work that can be conducted at the outset of examination under Sections 102, 103, and 112.

Request for clarification from Senators Thom Tillis and Tom Cotton, 2021

The senators requested a pilot in which the SME analysis was conducted only after other rejections had been addressed. The senators noted that their discussion with examiners suggested that “by bringing claims into compliance with Sections 102, 103, and 112, examiners inevitably brought the claims into compliance with Section 101 as well.” The DSMER Pilot Program appears to be a result of that request.

The US Patent Office’s experiment

Invitations to participate in the DSMER Pilot Program (the Pilot) ran from February 1, 2022 to July 30, 2022. Prosecutions of the patent applications for those applicants who accepted the invitations are scheduled to continue over the next one to two years. The Pilot allowed the applicant to defer responding to a pending SME rejection “until the earlier of final disposition of the participating application or the withdrawal or obviation of all other outstanding rejections.” As a result, the applicant may focus an initial response and amendment on other areas of the Office action and defer any arguments/amendments directed to an SME rejection for a later response — if that SME rejection is still outstanding.

From a practical standpoint, this means that the applicant may defer the response to the pending SME rejection until the first final USPTO action or the filing of an appeal. As illustrated above, a first non-final action is typically followed by a final action, so the deferral of the response to the SME rejection may be for only a single Office action response. Once the first final Office action is issued, the applicant will be required to respond to the SME rejection in any further prosecution.

If the amendments provided to address non-SME rejections overcome the SME rejection, then the SME rejection does not need to be addressed, therefore streamlining the patent process. If the prior amendments do not address the SME rejection, the SME rejection must still be overcome, but the issues before the examiner and the applicant are focused on a reduced area of dispute.

Restrictions

Restrictions were included in the Pilot. First, the application must have been an original nonprovisional utility application or international application that has entered the national stage and may not claim benefit of an earlier filing date under 35 U.S.C. §§ 120 or 121 of any prior nonprovisional application. The application, therefore, could not be a continuation, continuation-in-part, or divisional application. However, the application could claim priority to a prior provisional application or international application under 35 U.S.C. §§ 119, 365, or 386.

And, the application could not have been advanced out of turn. Applications which were selected as Track One status or another fast-track program were, therefore, ineligible for the Pilot. Beyond these requirements, the application must have had an Office action issued by an examiner participating in the Pilot (a primary examiner) and have both an SME rejection and a non-SME rejection within the Office action.

Appeals challenges

Counsel and/or other applicants may wish to avoid participation in the Pilot — assuming they’ve applied or invitations are sent again — if they believe an appeal of an examiner’s rejection may be necessary if the response to the first Office action (in which a response to an SME rejection was deferred) results in a final Office action. In such an appeal, the applicant will be required to respond to the pending, but previously deferred, SME rejection. However, under 37 C.F.R §§ 1.116 and 41.33, amendments, evidence, and affidavits may only be provided after a final action for a “good and sufficient” reason. The USPTO has specifically stated that participation in the Pilot does not constitute a good and sufficient reason.

A participant in the Pilot, therefore, will be barred from providing an amendment, evidence, or an affidavit for the first time as part of their appeal arguments to overcome the pending SME rejection. Instead, the applicant may be required to file a Request for Continued Examination (RCE) to submit these elements for consideration. Alternatively, the applicant may provide the amendment, evidence, or affidavit as part of their initial response to the first Office action, but this might moot any benefit received from deferring discussion of the SME rejections. (It should be noted that a participant in the Pilot is not forbidden from responding to a pending SME rejection.)

Progress or placebo?

Though no longer offering invitations to participate, the Pilot is a potential view into solutions being considered by the USPTO to address the growing confusion regarding subject matter eligibility for patents. As a solution, deferring a response to SME rejections offers minor benefits, but includes additional challenges as well. For example, deferring the response to the SME rejections may allow for the response to be more concise, and may avoid placing statements on the record regarding patent eligibility that may be used to restrict the interpretation of any granted patent. The benefits are relatively short-lived, however, and may not be worth complicating an appeal.

The Pilot represents an interesting shift in the USPTO prosecution process and appears to acknowledge the opportunities for improvement of the handling of

SME rejections.

To date, it appears the reception to the Pilot invitations has been lukewarm. Invitations were sent to 600 potential participants, but only about one-third were accepted. Data is not yet available on how many rejections based on SME will be ultimately obviated without requiring a response.

Opportunities for improvement

It remains to be seen whether the Pilot will improve prosecution history in the area of SME rejections, or whether it will be incorporated as a standard procedure within the USPTO. The invitation-only aspect of the Pilot, as well as the relatively short deferral (potentially for only a single response), may limit its appeal to some applicants. Nonetheless, deferring a response to SME rejections, if available, may be an attractive option to applicants that would like to reduce on-the-record characterizations of their application that may be necessitated by a response to an SME rejection. The Pilot represents an interesting shift in the USPTO prosecution process and appears to acknowledge the opportunities for improvement of the handling of SME rejections. The results of the Pilot may lead to broader changes in the way such SME rejections are handled.

Disclaimer: The information in any resource in this website should not be construed as legal advice or as a legal opinion on specific facts, and should not be considered representing the views of its authors, its sponsors, and/or ACC. These resources are not intended as a definitive statement on the subject addressed. Rather, they are intended to serve as a tool providing practical guidance and references for the busy in-house practitioner and other readers.