CHEAT SHEET

- Customize. Your retention policy and schedule should address general legal and regulatory requirements that are industry and country specific.

- Consistent updates. Your policies and schedules should be updated every 12 to 18 months.

- Employee behavior. A successful records management program depends on employee adaption to the new process, which is accomplished through messaging, communication, training, and audits.

- Control + alt + delete. Part of retention is deletion; organizations should routinely delete unnecessary information.

During the past two decades, companies have largely switched from paper to electronic-based media for communications and information sharing. Yet, many records programs remain stuck in the past. While paper documents have given way to email, electronic documents, and other types of messaging, many records management programs are still based largely on a paper-centric paradigm. Furthermore, new compliance challenges in e-discovery, privacy, data breaches, as well as the need to keep employees productive have put additional stress on these outdated records management programs. Increasingly, companies are upgrading their paper-based programs into more comprehensive, modern, compliant, and easier-to-execute information governance programs that lower risk, increase compliance, and reduce costs — all while making employees more productive.

These older programs, especially in the era of electronic information, not only fail to drive compliance, but actually hinder it.

The problem: Traditional, paper-centric records programs don’t work for electronic information

Traditionally, records retention programs were designed for the retention and disposition of “official” paper records. Executing a records program came down to sorting the right paper into record storage boxes. This thinking still lives on in many programs:

- Many records programs continue to have an emphasis on paper records management, to the exclusion of the majority of records that are created or received in electronic media.

- They focus only on records with legal or regulatory requirements, while paying little attention to records with business need or business value.

- These programs are driven by longer, complex, and extremely detailed retention schedules, holding on to the misconception that a longer schedule was more compliant. Some retention schedules have thousands of lines for every single record in the organization.

- Very few employees actually follow, or in some cases, are aware that a records retention policy and schedule actually exist.

- The traditional approach places a heavy emphasis on creating a detailed policy itself, with little consideration on how the policy will be executed.

These older programs, especially in the era of electronic information, not only fail to drive compliance, but actually hinder it. Worse, the lack of a viable program drives up both offsite paper and electronic storage requirements and costs, increases risks and costs during litigation, and hampers privacy. A more modern and effective approach is needed.

How to get there: Start with a modern, compliant, and easier-to-execute records retention schedule

Updating the retention schedule to be modern, compliant, and easier-to-execute is often one of the first steps companies take to modernize their program. But what makes a records retention schedule good? How do you craft a schedule that works better in today’s information environment? By creating, updating, and executing hundreds of records retention schedules over the years, we have identified some common attributes.

Compliance. Does your retention policy and schedule follow all the rules? An immature retention policy does not consider the rules, does not provide the legal basis for retention periods, and does not mandate disposition of expired information. As a schedule matures, it should address general legal and regulatory requirements, as well as any industry-specific regulations. For global companies, the most mature schedules include country-specific retention requirements. This is an elemental requirement of any schedule.

Comprehensiveness. Does your schedule represent all of the records in the organization? Companies often try to take shortcuts by copying from industry templates or sample schedules that purport to include all records a company in that industry should have. These “out of the box” schedules will typically describe around 80 percent of company’s records. What they omit are the 20 percent of records that may be atypical for your company. Effective schedules are comprehensive and capture all — both typical and uncommon — record types.

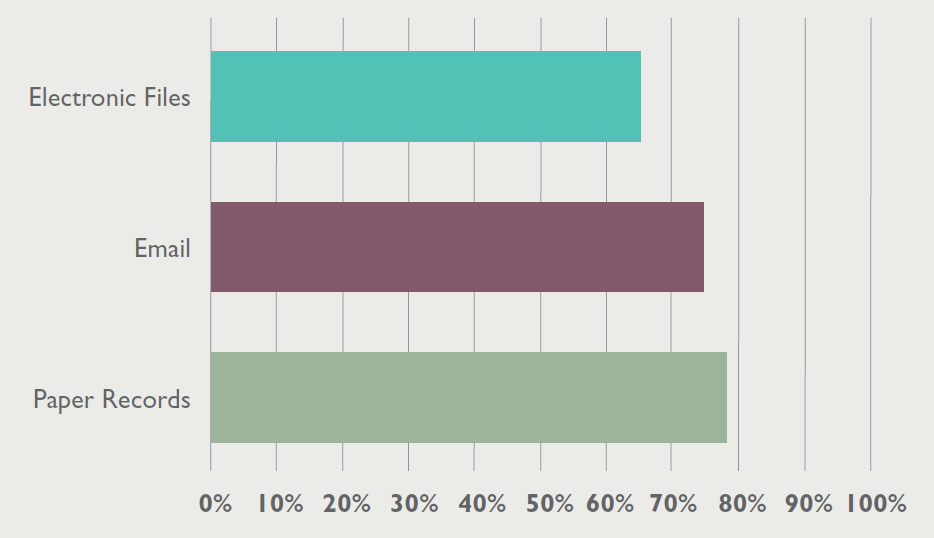

Media. Does the schedule look across all media formats where records may exist? The oldest (and often the least mature schedules) address only paper or a subset of the media present in the organization. Today, many records — some exclusively — exist in newer media such as email, files, and even social media. Also, don’t forget about physical items that may qualify as records — lab specimens at life science companies, or even shoe design samples at shoe manufacturers. A more mature schedule includes all media types and will help change the mindset that your schedule only applies to paper records.

Clarity. An effective policy and schedule clearly define “What is a record?” and “What is not a record?” Likewise, it details what records must be kept, and what can be destroyed. Finally, a policy and schedule should be both informative and clear: It should list examples and define non-records, while avoiding esoteric acronyms and incomplete definitions.

Consensus. Often a records initiative is driven by one group in the company — sometimes legal, sometimes compliance — and little effort is made to engage the rest of the business. The result are rogue business units that either refuse to follow it or push back on its requirements. Such efforts are often seen as “legal poking its nose in our business” or “encroaching on our territory” and are therefore unwelcome. An effective schedule reaches out to multiple groups and stakeholders. It makes the case for why a policy and schedule are needed, and gains support for its enforcement.

Usability. The most practical schedules provide a “Goldilocks” approach to retention schedules … just enough information — not too little, not too much. They use a format that is easy to read and organized in a way that all employees can follow. A usable schedule follows a “Big Bucket” approach, with a small number of record categories; rather than a “Small Bucket” approach, with hundreds or even thousands of record line items. Additionally, a usable schedule should be concise — it doesn’t list every single record or example for a particular record category.

Integration. A mature retention policy and schedule should be integrated into an overall information governance program that includes data classification, privacy, collaboration, and litigation readiness. A well designed schedule should be a useful tool in all these functions. The data classification and privacy components of your information governance program should leverage the schedule to understand what types of records exist, and if they contain confidential information, privacy, or intellectual property that needs to be protected.

Defensibility. Both a retention policy and schedule must be defensible, in the event they must ever be defended in court or to regulators. Defensibility also means ensuring employees are in compliance and actually following the policy. If there is something in the policy that your employees cannot follow, it should be rewritten to enable compliance.

Maintenance. A schedule is a living, breathing document that must be periodically reviewed and updated. As new record types are created, old record types become obsolete and legal citations change all the time — not to mention new recordkeeping regulations that come into play.

Update your policies and schedules every 12 to 18 months, and follow up with updating your implementation processes and procedures.

Records management gut check: Are you doing the right thing?

In records management it’s tempting for in-house counsel to focus on its area of expertise — creating the “most legally compliant” policy. Yet, having a policy in itself does not compliance make. Regulators and courts judge compliance on how well a good policy is executed. They ask: What did you say you were going to do in your policy? What are the processes, training, and controls you used to execute your policy? How did you follow up and audit your efforts? Did you really do what you said you were going to do? Policy creation, therefore, should have a constant eye on execution. If you cannot execute what is stated in your policy, take a step back and redesign your policy so that you can. This records management “gut check” should guide you all the way through your efforts.

Don’t forget about employee behavior change management

Now that you have your policies and processes, roadmap, tools, and technology in place, you may think you are done. We are not there yet. The most overlooked and critical piece of records management programs is employee behavior change management.

Employees have developed habits over years and sometimes decades of storing email and files in their preferred locations, be it file shares or offline email “PST” files on their desktops. As part of a revamped records program, we want them now to store this information someplace else, typically a content management or archive system we defined as part of the data placement process. Just telling employees to change typically does not work. Nor does simply threatening them that they need to adapt to a new process. You can have the best policies and technologies, but if employees are not using them, all is for naught.

Can we depend on employees to simply self-declare program compliance?

One approach to records management compliance is through employee self-certification. Employees are expected to acknowledge their compliance with the records policy by clicking a link sent in a monthly email, and those who fail to acknowledge it face disciplinary action. While we like the apparent simplicity and ease of this approach, our assessments of records program compliance have shown self-certification does not really work. Employees tend to follow the process initially, but some fall behind in their compliance. They declare their compliance, thinking to themselves they will catch up classifying all their records, but month after month they fall farther behind. The acknowledgements continue, but this is not matched by actual record compliance, and this becomes a major issue during a regulatory inquiry or litigation.

What does work is implementing a change management process. Change management is a formal discipline that combines messaging, communication, training, and audit to get employees to follow a new process. When organizations effectively apply change management, even stodgy, disinterested, or even recalcitrant business groups will get on board.

Change management has several different components:

Message and communications strategy. This includes audience segmentation, message development, and training plan development.

Employee training. Training can assume a variety of formats including classroom, webinars, and Computer-based training (CBT) supplemented with training aids, guides, and FAQs.

Pilot and rollout. A pilot ensures that a company is ready to roll out the new process, procedure, or technology to large groups or the entire enterprise, depending on the total size of the company, geographic distribution, and nature of the technology being deployed. Some changes to training materials, training, solution architecture, solution configuration (or even components), and backend support may occur based on the results of the two activities.

Audit and ongoing remediation. The regular examination of user and system conformance and compliance to intended rules is important not only for ensuring that the approach is working, but also for providing program defensibility in the event it is challenged. Results of ongoing audits drive regular re-examination and refresh of policies, processes, and procedures.

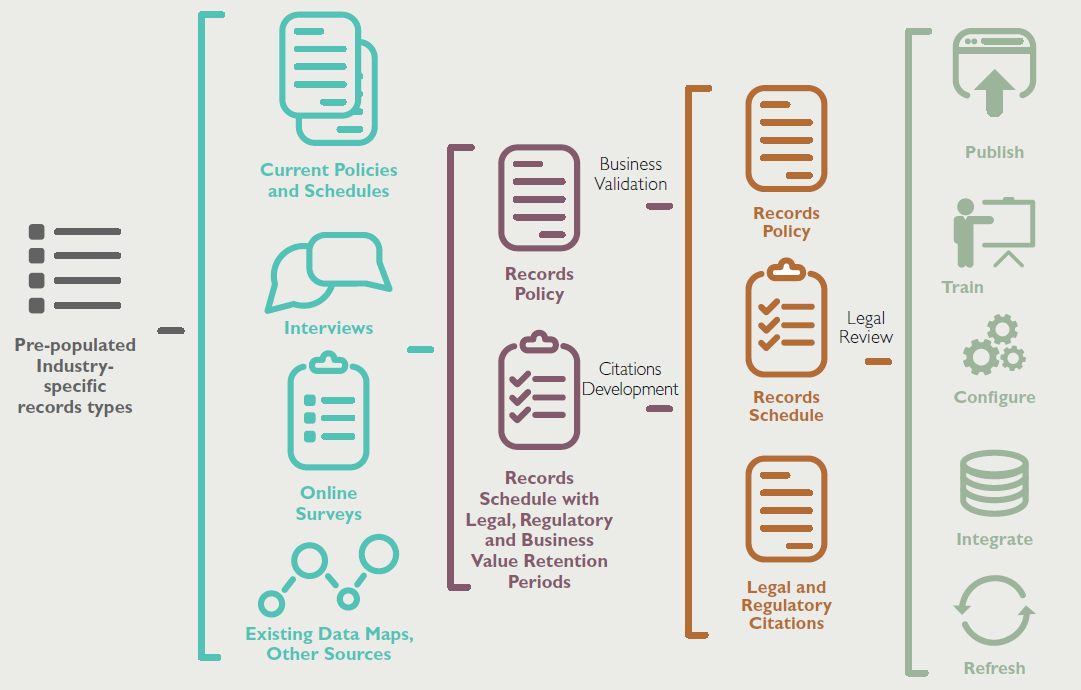

Figure 1

Records schedules are best created through a combination of in-person interviews, phone interviews, and online surveys, as well as tapping into other sources such as existing data maps.

Defensible disposition of unneeded files and emails

The discussion thus far has focused on upgrading records management to save the right information. While modern programs are good at saving the right information, they are even better at getting rid of expired records and low-value business information.

Organizations should routinely delete unnecessary information. Making disposition repeatable and consistent are the pillars of a defensible records program. We advise that companies struggling with defensible disposition start by forming a cross-functional team to examine current information management and legal response processes. Establish communication among the legal, records and information management (RIM), and IT departments, as well as executives and end users. Everyone must think beyond traditional processes to see the value of a defensible disposition program.

Identify the business “pain” so that you can explain — as specifically as possible — how defensible disposition and managed retention programs will yield measurable benefits. For example, consider “hard” cost savings, such as postponing storage expenditures, as well as “soft” cost savings, such as reducing the amount of time spent by employees searching for information or working through litigation holds. Having a cross-functional team in place will help you portray the program as a win for all stakeholders.

Why defensible disposition programs stall out

The need to defensibly dispose of information is clear. Why is it so difficult for companies to proceed with confidence?

FEAR OF SPOLIATION. One of the most common obstacles to defensible disposition is the concern that the disposal of business content could be misconstrued as spoliation in certain situations. A lack of consistency or confidence in legal hold processes may cause the legal department to suspend deletion activities.

UNCERTAINTY ABOUT RECORD RETENTION REQUIREMENTS. Even when a retention schedule is in place, it may be misunderstood or simply not followed. As a result, individuals may carelessly delete information that should be saved.

LACK OF AGREEMENT ON THE BUSINESS VALUE OF RECORDS AND DOCUMENTS. Some record retention schedules reflect only the minimum legal and regulatory retention requirements for records. But they may not take into account additional operational or business requirements for both record and non-record content, which may result in longer retention requirements than the legal or regulatory minimums.

EMPLOYEE RESISTANCE. Employee resistance is one of the biggest obstacles to implementing a defensible disposition program. In some cases, employees have little or no training or guidance on the rules and procedures for proper document classification. This can create a lack of confidence on behalf of the employee — “I might get in trouble if I misclassify this document and it turns out to be a business record.”

NOT KNOWING WHERE INFORMATION RESIDES. By not having a complete inventory of where business content lives and what applications generate or consume it, information is effectively outside of the control of the organization. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, to apply consistent disposition policies.

Leverage team resources to create an information types inventory (ITI). An ITI is a detailed and comprehensive list of all types of documents and information across the organization. It details not only record types, but also privacy and other types of information, as well as what information resides in which repositories.

Covering the basics will force the team to grapple with estimating the value of the information that is held by the organization. Who needs it? Does it support ongoing operations? Are there outside rules and regulations that mandate its retention?

Figure 3

Sample messaging as part of an employee behavior change management program from a global manufacturer. This program developed a series of fun characters that played off types of undesirable behaviors. The messaging resonated and worked well in a complex, global company.

Cleaning paper record storage

While much of the focus on information governance is on electronic information, many companies are still burdened with huge stores of legacy paper records. Over-retained records (and other non-record extraneous materials) result in higher cost beyond that charged by offsite storage vendors (which in itself can be extremely expensive). For example, paper records are subject to discovery in the event of a lawsuit or request from regulators. These discovery costs can be costly but can be reduced by decreasing the amount of paper that must be searched and by scheduling regular remediation efforts that start with an accurate inventory of what is in storage.

Paper disposition often follows the same steps as electronic information: First, establish your policies to include an up-to-date records retention schedule and legal hold process. Next, identify the locations of paper records. Companies are often surprised where they find these boxes being stored. Next, develop a repeatable, documented process for classifying these records. Everything outside of the retention policy and not under legal hold can go. Again, put faith in your process. Paper records often have the advantage in that they are stored in a location this is not easily accessible by employees. Thus, paper records disposition often requires much less buy-in from the employees and business units.

Figure 4

Disposition targets. Average percentage of expired records and low-business-value information that can be deleted while maintaining compliance and retaining information still needed by the business.

Final words

When most records were created and stored on paper, records management was a relatively straightforward process. Then the world changed. Information switched from paper to electronic media. Recordkeeping regulatory requirements increased. Companies faced new requirements, such as privacy. Data began accumulating, e-discovery demands increased. The simple job of records management became more difficult.

In-house counsel may ask themselves: how do we know we have it right? They start looking for the perfect policy, the perfect process, and the perfect tool. We are not ready to start, they tell themselves, because we’re not quite there yet. In the meantime, documents and data accumulate, requirements become stricter, and risks increase. Perfect becomes the enemy of “good enough.”

Records management is inherently an imperfect process. Fortunately, the courts and regulators do not expect perfection. Rather, they expect reasonable good faith efforts. In your policies, declare what will be done. Execute those policies with processes, technology, and training. Demonstrate that policies are being complied with thorough metrics and audits. Show that a plan has been developed. Show that the plan is being executed. Audit the results and remediate any shortfalls. Not perfect? That is OK. No one expects it to be perfect. Start with good and just keep moving forward.