Banner and intermittent artwork by autsawin uttisin, Hitdelight, Stephen M Brooks, Klara_Steffkova, and Bildagentur Zoonar GmbH / Shutterstock.com

In this three-part series, you will learn how to best prepare your organization to respond promptly and lawfully to a search warrant. Part one covers readiness, preparation, and the kick-off of the search warrant response. Part two dives deeper into developing a search warrant response plan. And part three explores training via a simulated role-playing exercise.

Cheat Sheet

- Scope of search. Know the breadth of “things to be seized” — and avoid expanding the scope of search inadvertently by consenting to additional requests outside of this scope.

- Preparation is key. When a search warrant is executed, your employees are often on their own; be sure they know what to do to avoid unnecessary headaches.

- Good housekeeping. Keeping things tidy in the workplace can pay off. Items “in plain sight” may be subject to search or seizure.

- Develop a plan. Be prepared to respond to a search warrant effectively by equipping employees with a search warrant response plan.

Zero hour

You are the deputy general counsel reporting to the general counsel in a two-person law department. Your company owns and operates warehouses and distribution facilities up and down the West Coast. You are primarily responsible for negotiating many of the company’s agreements, including warehouse leases, distribution agreements, and shipping contracts. Many chemical manufacturers enter into distribution agreements with your company, which has developed a reputation for safely storing and distributing their products.

Working from home that morning, your mobile phone pings with a text: “ALERT: Law enforcement officers just arrived with a search warrant. See photo.” It is from the receptionist at one of the company’s facilities. The photo is the front page of a search warrant. You read it, confirming that the company name and facility address are both correct, the warrant was issued by a federal district court, it is dated yesterday, and it is signed by a judge.

Another text arrives with a photo of the warrant’s scope of search. It lists the items to be seized, including documents, business records, bills of lading, invoices, and contracts pertaining to your company’s most important chemical manufacturing client. The scope also lists the seizure of computer hard drives, data storage media, and servers. Finally, it authorizes the taking of air, water, and soil samples from the premises to determine the presence of certain chemicals.

You call your general counsel, Dawn, but she had just gotten on a flight to Doha that morning. So, you send her a text instead, hoping she reads it once her mobile is connected to Wi-Fi. “Dawn. Just got served with search warrant. Will handle. Vince.”

After getting a third text with pictures of the officers and their business cards, you call the receptionist as you get into your car to drive to the facility an hour away.

“Hey, Jin. This is Vince. Thanks for the texts. I am on my way. It may take me an hour.”

“Hi, Vince. Thanks for calling. No need to rush,” Jin replies.

Puzzled, you ask, “Are you saying the officers are willing to wait until I get there?”

“No. In fact, they just started the search,” she responds. “But no worries, we got this. Last month, Dawn trained us on how to respond to a search warrant. She said, chances are, all of us here would be on our own until either she or you arrive.”

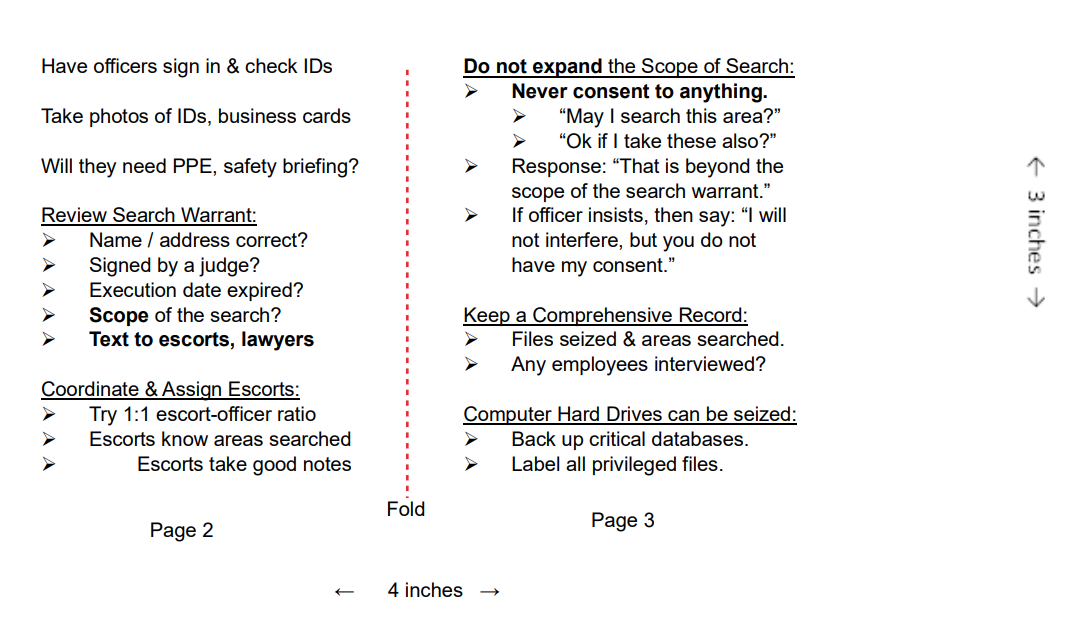

Jin continues: “The training session was very instructive. We even did a mock search warrant role-playing exercise. Afterwards, Dawn gave each of us this handy, credit card-sized checklist of what to do and not do, so we did not have to look for the training binder. I keep my checklist in my mobile phone case. It even has the attorneys’ mobile numbers on it.”

Preliminary considerations

Your employees are on their own.

You hang up and ponder as you drive to the facility. How brilliant of Dawn to have trained the employees. You remember how some time ago your outside counsel, Alyse, gave a search warrant presentation to you, Dawn, and the company’s executives. Alyse had emphasized the need to train the frontline employees — receptionists, guards, facility managers, etc. — especially those in remote locations. Since the officers executing the warrant will not wait for an attorney to arrive, the employees onsite must know how to handle the situation on their own, at least during the first hour or so.

Interfering with the search is the worst thing they can do.

The employees must know not to interfere with the search and not to destroy or delete anything once the officers arrive with a search warrant. If these officers observe an employee shredding a document or deleting an email, they will immediately conclude that the employee is destroying evidence that could be considered obstruction of justice, a serious offense. This could lead to criminal charges being filed against the company and the employee, regardless of whether the search itself turns up anything incriminating. Even the appearance of tampering with the scene such as moving boxes or other items might arouse unnecessary and unfounded suspicion. It is best that while an employee may observe the search to ensure that only authorized areas are searched, employees should keep their hands off any items to be seized.

Good housekeeping is a must.

The employees must also ensure that their “house” is kept neat and tidy. The “shock and awe” of law enforcement officers executing a search warrant and interrupting their daily routine can cause employees to forget about the documents and materials they left spread across desks and workspaces. Regardless of what is in the scope of the search warrant, if officers see anything suspicious “in plain view,” they can seize it.

Have a search warrant response plan.

Finally, the facility should have a search warrant response plan in place, including a team of employees who are trained to interface with the officers and accompany them during their search. The response team members should be equipped with their mobile phones, notepads, pens, and containers for taking split samples if the officers are there to collect samples. They each must know how to use these tools when escorting the officers around the facility. And they also need to know how to communicate with the officers in a cooperative yet cautious manner without volunteering information or consenting to expand the scope of search. There should be a pre-designated team leader who will liaise with the officer in charge before, during, and after the search and negotiate with the officer in charge to have each officer escorted by a team member to ensure safety. If possible, the team leader should have an assistant taking contemporaneous notes of the entire event.

Even the appearance of tampering with the scene such as moving boxes or other items might arouse unnecessary and unfounded suspicion.

Search warrant basics

What is a search warrant?

A search warrant is a court order issued by a judge or magistrate that authorizes law enforcement officers to conduct a search of a specific person, location, or vehicle for evidence related to a crime, according to Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute.

It is issued based on a sworn affidavit, usually by an investigator or law enforcement officer, indicating the existence of probable cause that a crime has been committed and demonstrating the need to seize a person or property in the premises to be searched.

It is grounded in the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution which states:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

The right to be secure from unreasonable searches and seizures extends to corporations as well as business premises.

What are the elements of a search warrant?

A search warrant must contain the following elements:

- The court issuing the search warrant and its jurisdiction;

- The matter name and case number;

- The name and address of the person or place to be searched or seized;

- The items or persons to be seized (a.k.a. the scope of search as further discussed below);

- The deadline for executing the warrant;

- The date and time the warrant was issued; and

- The name and signature of the judge issuing the warrant.

A search warrant that is missing any of these items — e.g., has the wrong address, an incorrect company name or address, an incorrect execution date, or no judge’s signature, etc. — is arguably defective or invalid, which supports claiming that the officers have no authority to conduct a search or to seize items. These kinds of deficiencies, however, may be considered technical violations, which will not automatically invalidate a warrant, as shown in United States v. Pelayo-Landero.

In addition, a search warrant must be executed in accordance with applicable federal or state criminal procedure requirements. For example, a federal search warrant is subject to Rule 41 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which requires that it must be executed during the daytime (i.e., between the hours of 6 am and 10 pm, local time, unless the judge authorizes execution at a different time) and within 14 days of issuance, though this could be 10 days in some jurisdictions. Further, this issue can be litigated as the information seized is presumptively stale, but that presumption can be overcome in certain circumstances.

The rule also requires that the officer executing the search warrant create an inventory of the property seized during the search in the presence of another officer and the person from whom the property was seized, and provide that person with a receipt of the property seized and a copy of the warrant.

If the warrant has been executed in a manner inconsistent with these requirements — e.g., executed 15 or more days after issuance, no inventory created, or no receipt given — then such deficiencies would support a claim that any items seized may not be entered into evidence and must be immediately returned. Several courts have held, however, that violations of Rule 41 are merely technical or ministerial violations that do not necessarily render evidence seized inadmissible, unless the violations prejudice the defendant or the evidence demonstrates that the law enforcement officer showed intentional and deliberate disregard for the rule's requirements.

Scope of search

What is the scope of search?

The scope of the search is defined by the detailed description or list of ”things to be seized” which are directly related to the subject matter of the search warrant, to the extent these things constitute evidence of a crime, fruits of a crime, or things for use in a crime. The list can include “documents, books, papers, any other tangible objects and information,” as well as electronic storage media or electronically stored information.

In the case of a search warrant executed based on the probable cause that an environmental crime may have been committed, for example, the scope of search would also likely include obtaining media (e.g., air, water, soil) samples for analysis in a laboratory. In such a situation, you should ask the officer for a copy of their analytical report and compare it with your analysis of split samples taken by the employee-escorts during the search.

Only items that fall within the scope of search can be lawfully seized. If the officers have items that fall outside the scope of search, the company can and should object to their seizure. The government can overcome such objections, however, if they can show that either (1) the items seized were “in plain view,” or (2) the company consented to their seizure.

One way to avoid having items seized because that are “in plain view” is to maintain good housekeeping by minimizing the clutter of documents and materials on employees’ desks and in their workspaces. But how do you avoid consenting to the officers expanding the scope of their search? By recognizing when officers become overly courteous.

How do you avoid expanding the scope of search?

When the officers start asking, “May I search this area?” or “Do you mind if I take these also?” your employees need to know that these officers are seeking to expand the scope of the search by surreptitiously obtaining the employees’ permission or consent. By responding “yes” or “I don’t mind” to these questions, an employee may inadvertently give consent to searching an area or seizing a document that does not fall within the scope of search.

Then how should an employee respond? By politely saying, “Sorry, but no,” and stating that that is beyond the scope of the search. “No, you may not take those items, because they fall outside the scope of the search warrant.” If the officers persist, then the employee should respond by saying, “I will not interfere, but you do not have the company’s consent to do so.”

By responding “yes,” an employee may inadvertently give consent to searching an area or seizing a document that does not fall within the scope of search.

Why would the government want to use a search warrant in the first place?

A search warrant is usually the last option a government agency will use to obtain information, given the amount of planning, coordination, and resources involved, not to mention the need to maintain secrecy prior to executing the warrant. This option would only be triggered if the government believes there is the likelihood that evidence would be destroyed if the company is on notice of the investigation, or a company is uncooperative or unresponsive to official government requests for information – a posture that can be avoided by immediately involving a company’s lawyers at the outset.

An agency such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), for example, has statutory tools for getting information from regulated parties. Section 114(a)(1) of the Clean Air Act (CAA), for instance, gives EPA the authority to demand the production and submittal of information that EPA “may reasonably require” for the purpose of “determining whether any person is in violation of” a CAA standard or requirement. Failure to respond to a CAA §114(a)(1) information request could result in an EPA enforcement action and monetary penalties.

One way to avoid search warrants is to maintain good working relationships with the government agencies that regulate your industry and your company. Doing so requires, among other things, responsiveness whenever these agencies contact the company and request information that the government is likely already authorized or entitled to obtain.

Develop a search warrant response plan

According to Jessalee Landfried, a principal at Beveridge & Diamond PC, the ultimate goals of an effective search warrant response are to:

- Manage the event as smoothly as possible.

- Prevent panic by keeping employees calm and informed.

- Provide documents and items that the government is legally entitled to receive.

- Expedite the search to minimize business impacts.

- Protect and preserve the legal rights of the company and its employees.

- Maintain the integrity of privileged and proprietary information and documents.

- Gain valuable insight into the underlying allegations that prompted the investigation.

As stated above, it is important for employees to be prepared to handle a search warrant on their own, since law enforcement officers will not wait for the company’s attorneys. Therefore, you need to prepare a search warrant response plan that includes the following elements:

- How to review a search warrant

- How to receive law enforcement officers executing a search warrant

- How to organize a search warrant response team

- How escorts should interact with officers during a search

- Interview guidelines for employees

- How to handle certain items being seized

- How to conclude the search

Each of these elements will be covered in depth in part two of this series, Under the Microscope: Developing a Search Warrant Response Plan.

Disclaimer: The information in any resource in this website should not be construed as legal advice or as a legal opinion on specific facts, and should not be considered representing the views of its authors, its sponsors, and/or ACC. These resources are not intended as a definitive statement on the subject addressed. Rather, they are intended to serve as a tool providing practical guidance and references for the busy in-house practitioner and other readers.