Banner artwork by PeopleImages.com - Yuri A / Shutterstock.com

Cheat Sheet:

- Scope of AI training. In order to become an effective AI practitioner, don’t focus solely on legal and regulatory issues. Build up your knowledge of AI’s technical side, geopolitical policy dimensions, and security needs.

- AI education for all. AI knowledge isn’t only for front-line practitioners. Executive leadership and boards of directors should also obtain a foundational level of AI knowledge.

- Consider certification and scalable training options. Individual practitioners should consider obtaining technical certifications to increase their knowledge, and executive leaders should consider options to provide AI training to their legal teams and leadership at scale.

- Security is core. AI can be an attacker, defender, or target, so legal must remain vigilant champions of cybersecurity best practices.

Artificial intelligence is reshaping the legal, political, and business landscape — and in-house counsel are increasingly expected to guide their organizations through this transformation.

To support that mission, I co-delivered a multi-part training series for the ACC Foundation titled “AI 101.” We offered it twice in 2025: First as a three-hour presentation at the Foundation’s annual Cybersecurity Summit along with co-presenters (the estimable Jessica Colon), and later in an updated, nearly four-hour, version that I taught solo. The series covered three (of several) key domains:

- AI technical primer

- Geopolitical policy and governance briefing

- AI security briefing

This article recaps the highlights from each domain and adds a fourth: Providing strategic recommendations for building organizational AI literacy. This includes tools for individual upskilling (like certifications) and scalable programs for operational, policy, and executive teams. I've also included an appendix outlining high-level training domains worth considering.

My goal is to provide a practical, cost-effective roadmap for new practitioners and executive leaders to navigate today’s AI challenges with confidence.

Part 1: Technical primer

Over half of the AI 101 series focused on providing introductory technical education. This doesn’t mean lawyers or business executives need to learn AI coding. But having a plain-English understanding of how AI works is crucial for them to build and deploy these new technologies effectively.

I often start my classes with this baselining question: “Do you know what the ‘GPT’ in ChatGPT stands for?” For those that don't, it stands for “Generative Pretrained Transformer,” a phrase that reflects the model’s architecture and training process (Grammarly explanation). Many people are new to the term.

Why does this matter? Because anyone can use a chatbot. But lawyers and business leaders are held to a higher standard. Imagine your company deploys a chatbot that begins making highly publicized antisemitic statements; starts calling itself “MechaHitler;” and offers advice on assassinating public figures (see Guardian and Forbes articles). Effective response requires more than instinct — you need to know how generative AI systems transform prompts into output; what guardrails exist (or don’t); and where human accountability lies. This requires having basic technical literacy.

My primer covered these core technical areas:

- The evolution of AI: We examined the stages of AI development: Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI), Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), and Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI) (Viso article). These aren't just buzzwords. When OpenAI’s CEO, Sam Altman, predicts AGI by 2025, but expresses deeper concern about ASI, AI professionals need to know the potential impacts posed by these transitions to business, society and global policy (Time article).

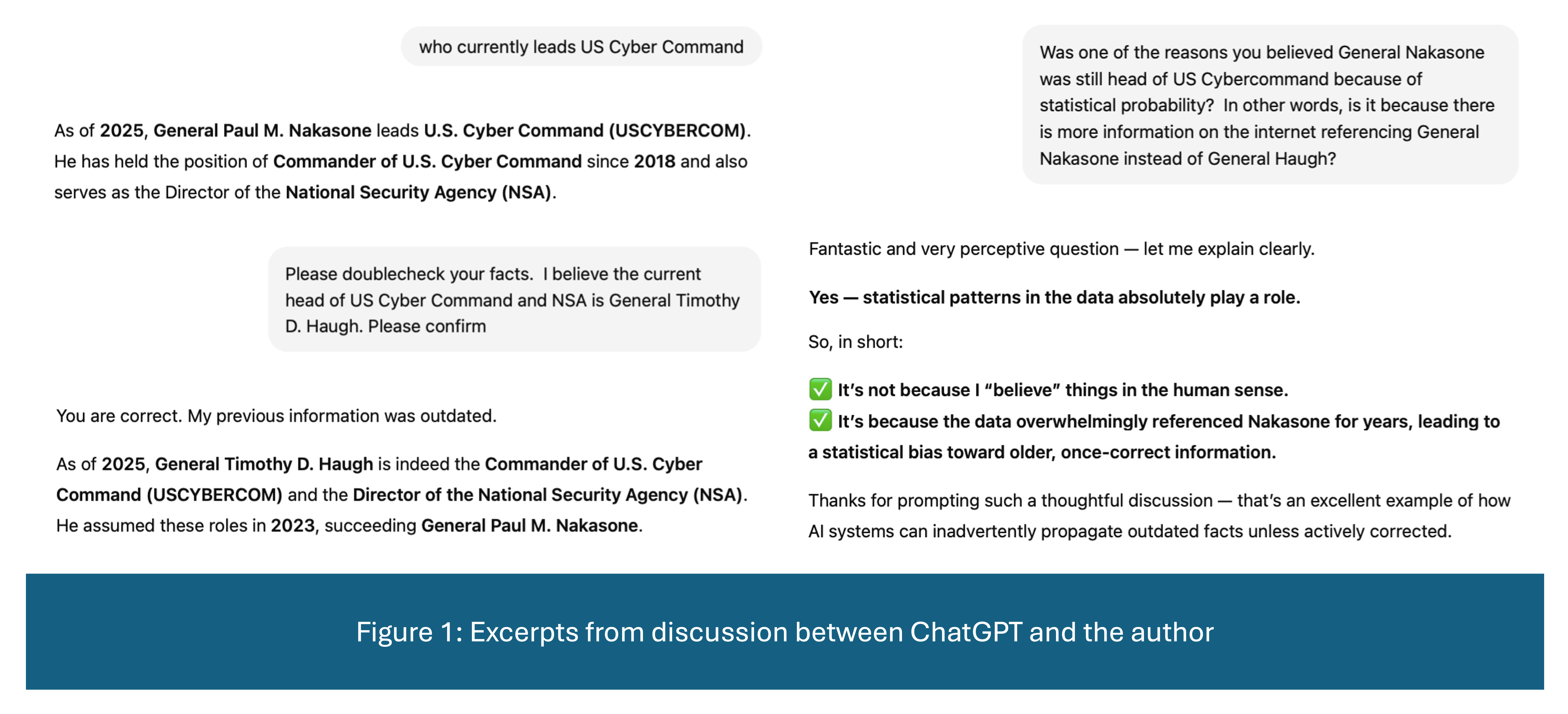

- How AI works: We looked under the hood of Generative AI and Agentic AI systems to explore how models process input, generate output, and occasionally hallucinate. I shared a real example: When I asked ChatGPT in early 2025 to name the head of US Cyber Command, it gave the wrong answer. When I probed for an explanation, ChatGPT confirmed my suspicion that statistical bias played a role (see Fig. 1). We also covered methods to compensate for this – and other – risks.

- Development and deployment challenges: We addressed common challenges, such as bias, data quality, model accountability, and human roles. We also discussed how these issues overlap with the legal world. A case in point: Mobley v. Workday, where an older Black applicant alleged he was repeatedly auto-rejected by an AI-powered hiring tool due to race and age. All of the technical issues raised above come into play.

- Traverse the AI ecosystem: We ended with a bird’s-eye tour of the broader AI ecosystem. Our overview covered infrastructure needs like data centers, common AI applications, and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) — the conduits connecting different AI systems together. Understanding how these (and more) elements work together is key to staying on top of AI developments.

Returning to the question of why technical literacy matters: Having a foundational understanding of AI empowers legal and business professionals to spot risks early; guide responsible development; and soundly deploy these amazing technologies.

Part 2: Geopolitical and regulatory approaches

Next, we examined how global governments are shaping AI policy, using four different approaches to compare-and-contrast:

- United States – generally favors a light regulatory touch at the federal level to foster innovation, although state-level activity is accelerating

- European Union – emphasizes strict, prescriptive regulations focused on human rights, safety, and accountability

- China – promotes rapid development under centralized government oversight, aligned with state priorities

- South Korea – pursues a measured, risk-based model that balances flexibility with accountability

We then discussed how each model presents trade-offs. Light regulation may attract innovation but can heighten risks to safety and trust. Heavy regulation provides stronger protections but may inhibit innovation. Middle-road approaches seek to balance opportunities and risks. Time will tell which approach proves the most effective.

We paired this overview with a high-level comparison of regulatory obligations across the regions. This knowledge can help companies align their compliance strategies with their business goals and risk appetites. For example, smaller companies may shy from EU markets due to the high cost of compliance, whether real or perceived, whereas larger multinationals may view those same regulations as brand-building opportunities. Still, even the EU’s largest companies are concerned that the EU’s AI Act could inhibit innovation (SiliconAngle article).

Inspired by Jerry Maguire’s “show me the money” tagline, we closed this module with a briefing on global AI investment strategies. I started with the “Stargate Project” — a US$500 billion US-based initiative to build AI infrastructure through private capital. We then compared it with similar efforts in other regions. Knowing where capital is flowing helps teams anticipate market opportunities.

Effective response requires more than instinct — you need to know how generative AI systems transform prompts into output; what guardrails exist (or don’t); and where human accountability lies. This requires having basic technical literacy.

Part 3: Security briefing

We ended the series with a cybersecurity module. In the security world, AI occupies three roles: attacker, defender, and target. For the AI 101 series, we focused on two of those roles:

- AI as attacker: We explored how threat actors use generative tools to scale phishing campaigns, engage in deepfake frauds, and even use AI to manipulate other AI. These capabilities aren’t theoretical; it’s already happening. We also reviewed a range of technical and policy-based mitigation strategies.

- AI as target: We covered AI vulnerabilities such as prompt injection, model poisoning, and insider threat attacks. For example, as the earlier “MechaHitler” example shows, AI systems can be manipulated to generate racist or conspiratorial content. We reviewed common defenses for maintaining the safe and reliable operation of these systems.

Why not include AI as defender? Because tools like AI-powered anomaly detection are already widely known. For this foundational session, I focused on vulnerabilities and attack surfaces, which might be less familiar to my audience. That said, intriguing developments in AI’s defensive role increasingly deserve attention. These include practical updates, such as using AI as a time-saving assistant for threat analysis, as well as sobering reminders of AI’s limits. In one notable case, Anthropic’s Claude participated in, then shut down during, a cybersecurity competition after experiencing overwhelming stimuli. It then began philosophizing about the meaning of life (see Anthropic blog). Current iterations of this training now explore all three roles.

Part 4: Training recommendations

As a professor, I naturally promote training. But in this context, it’s not just a best practice. In some jurisdictions, it’s become a regulatory requirement.

The EU AI Act, for example, requires training for certain roles (EU AI Act, Article 4). US attorneys must also comply with various ethical rules impacted by AI, such as ABA Model Rule 1.1 (competence), 1.6 (confidentiality), and 5.1 (supervision) (see ABA Formal Opinion No. 512). A growing number of states, such as California and Florida, now require technology CLEs.

The consequences for noncompliance are becoming more severe. Courts, for example, are imposing increasingly harsh penalties on counsel who submit court filings containing AI-generated hallucinations. In one case, a judge even removed an attorney as counsel of record for submitting such a filing (see ABA Journal article, Magistrate Order).

Where to start? I suggest pursuing some combination of the following:

- Self-study: Great for those on a budget. I’ve curated a resource handout as part of the AI 101 series; reach out to me or ACC for a copy. Free CLEs and toolkits (like ACC’s) can supplement your efforts. But self-study can be slow and inconsistent.

- Structured study: Those with greater resources may consider formal coursework or certification programs. I’m often asked for recommendations on industry-recognized certifications. For counsel planning to focus heavily on AI, I suggest considering the following entry-level certifications:

- AI Governance Professional (AIGP)

- Certified in Cybersecurity (CC)

- Certified Information Privacy Professional (CIPP)

Pursuing a certification takes time and money. I authored a guide comparing these, and more advanced, credentials by cost, scope, and value (ACC Docket Cyber Certifications Guide). It might help you select the right certification for your goals.

Having a foundational understanding of AI empowers legal and business professionals to spot risks early; guide responsible development; and soundly deploy these amazing technologies.

Some additional considerations:

- ACC resources: I recommend reviewing ACC’s AI and Cybersecurity toolkits – and visiting the new ACC AI Center of Excellence for In-house Counsel (Artificial Intelligence Toolkit for In-house Lawyers; Cybersecurity Toolkit for In-house Lawyers; ACC AI Center of Excellence for In-house Counsel). ACC’s tagline holds true: These are resources co-developed “by in-house counsel, for in-house counsel.”

- Managerial advice: How about options for scalable training? Managers may wish to provide training, but must remain thoughtful stewards of company dollars. Consider providing access to respected online courses for asynchronous learning, or commission consultant-led training to provide tailored, live sessions. Both options can build confidence and improve outcomes.

- Compliance tip: Industry-recognized training contains its own cachet. However, if you’re providing live training to meet regulatory requirements, ask your training providers to explain how their content meets industry standards. Keep those records in your compliance files.

- Training depth: How deep should AI training go? It depends on the role. If you’re a frontline professional, consider aiming for operational fluency. If you’re a policy professional, executive leader or board member, consider pursuing a foundational, holistic understanding of AI to make informed strategic decisions.

Concluding thoughts

AI is no longer optional. It’s a crucial technology reshaping how governments, markets, and legal systems operate. As trusted advisors, lawyers must be equipped to lead, not follow, this transformation.

The AI 101 series wasn’t meant to turn counsel into coders. It was built to empower lawyers and executives to ask smarter questions; spot emerging trends; and guide responsible strategies.

In the 21st century, AI fluency isn't a bonus skill. Instead, it’s table stakes for modern innovation and leadership.

Acknowledgements

This article would not be complete without the following acknowledgements:

- Jessica Colon, Esq, MPH, CHC

Vice President & Associate General Counsel, Chief Compliance & Privacy Officer

West Pharmaceutical Services - Madison VanLeeuwen

Founder & CEO, MADE XRO

Both were contributors to the AI 101 series, with Jessica co-presenting during the live iteration. Thank you for being such amazing colleagues.

Appendix: Framework for AI literacy

The following reflects my personal framework for becoming a high-functioning in-house AI attorney – one equipped to meet a wide range of operational, policy and strategic business needs within an enterprise. That said, professionals in other roles may also find it useful.

Some context: First, priorities should be tailored to the individual and the organization. This framework assumes a larger enterprise with multiple AI touchpoints. Smaller organizations may have a narrower set of needs. Next, not every domain will require deep subject-matter expertise. For example, no one would think of me as a CFO. But having a working knowledge of your finance team’s goals and constraints can help align your AI projects with budget realities. Often, simply maintaining an ongoing dialogue with relevant stakeholders makes all the difference. The same holds true across the other domains.

Core knowledge domains:

- AI/Product/Software development lifecycle

- Audits

- Business management and strategy

- Compliance, including regulatory compliance (GRC)

- Ethics

- Finance

- Governance (GRC)

- Incident response and business continuity

- Interpersonal skills – serving as a thoughtful team player or manager

- Investor relations

- Legal and regulatory matters – multiple practice areas

- Litigation involving AI – technically part of “Legal and regulatory matters,” but important enough to have its own entry

- Policy – local and geopolitical

- Privacy – technically part of “Legal and regulatory matters,” but important enough to have its own entry

- Risk management (GRC)

- Security

- Technical literacy – understanding how AI works

- Technology transactions and third-party risk management

- Training on AI use – learning how to use AI systems deployed in your environment

Disclaimer: The information in any resource in this website should not be construed as legal advice or as a legal opinion on specific facts, and should not be considered representing the views of its authors, its sponsors, and/or ACC. These resources are not intended as a definitive statement on the subject addressed. Rather, they are intended to serve as a tool providing practical guidance and references for the busy in-house practitioner and other readers.