CHEAT SHEET

- Sanctions. Sanctions are economic measures or actions taken by one or more countries to influence the behavior, policy, or actions of target geographies, activities, or groups.

- Penalties. Noncompliance with sanctions, even unintentionally, can result in civil penalties and criminal punishments.

- Compliance program. Companies should develop a sanctions compliance program that has senior management commitment, risk assessment, internal controls, testing and auditing, and training.

- Screening. Use third-party vendors that have the software to screen customers, suppliers, resellers, and others against sanctions and export control lists.

As a general counsel for a US-based global provider of medical devices and with US President Trump announcing new sanctions practically every day, your CEO has asked you whether expanding your market to untapped places such as the Middle East (including Iraq and Iran) would be available to your company (including your European subsidiary) and, if so, whether it would require obtaining any licenses before the launch. The CEO would like to launch this market expansion next year. You begin to research whether you can do this and what would you need to do to make it happen.

Generally speaking, OFAC “primary” sanctions apply to US persons, meaning US citizens/permanent residents and US entities. However, certain sanctions programs extend jurisdiction extraterritorially.

Sanctions 101 — What are sanctions and to whom do they apply?

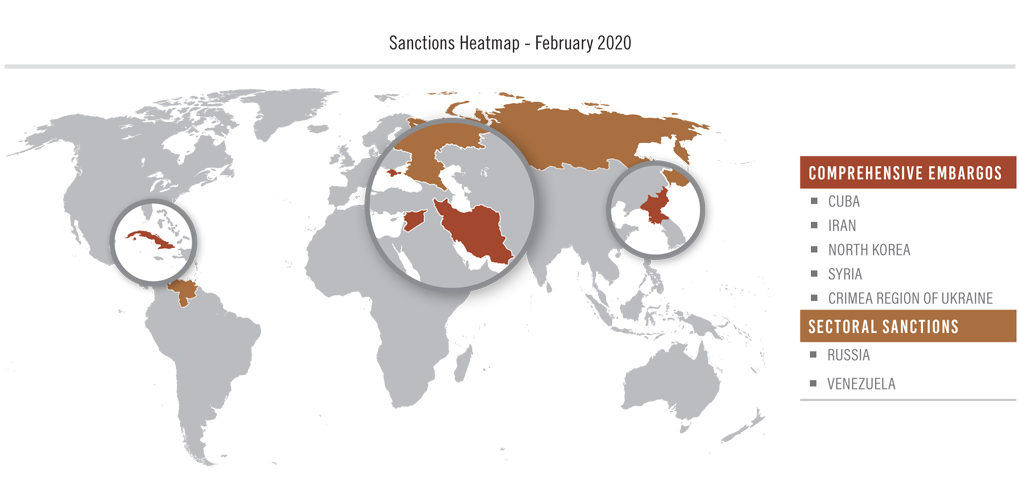

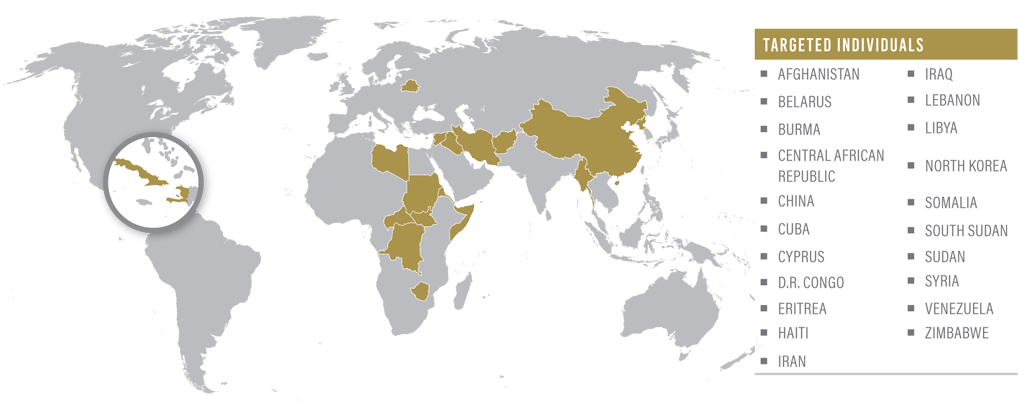

Sanctions are economic measures or actions taken against a target to influence its behavior, policy, or actions. They can be unilateral and multilateral. Unilateral sanctions are imposed by a single country while multilateral sanctions are imposed by multiple countries working together to impose sanctions against a target. Sanctions can also target geography or activities. Comprehensive geographic sanctions apply to specific countries or regions (currently, Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and the Crimea region of Ukraine). Other countries are subject to more narrow, targeted sanctions programs. For example, Russia is the subject of a new “sectoral” sanctions program that prohibits certain types of transactions with certain prohibited parties. Countries like Iraq and Sudan are also currently subject to narrow sanctions that only prohibit transactions with certain designated parties. Thematic sanctions focus on particular issues that may cut across geographic boundaries (e.g., counter-narcotics, counterterrorism, and cyber-related sanctions). Sanctions may also be used to protect the financial system from international criminals by influencing actions that lead to a reduction of money laundering, terrorist financing, and the trafficking of illegal goods by reducing the flow of funds.

The United States has more sanctions regulations than any other country and the greatest number of unilateral sanctions. Each country has at least one agency designated to administer and enforce sanctions within its jurisdiction. In the United States, the US Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control is responsible for enforcing sanctions, while the US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security administers the US export-control regime that often overlaps with sanctions issues.

Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)

OFAC is an agency within the US Department of the Treasury that is responsible for implementing financial sanctions based on US foreign policy and national security goals against targeted foreign countries and regimes, terrorists, international narcotics traffickers, those engaged in activities related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and other threats to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States (including human rights abuses and interference with democratic processes). A core component of OFAC’s sanctions regime is the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) list, which contains names of individuals and companies owned or controlled by, or acting for or on behalf of, targeted countries. It also lists individuals, groups, and entities, such as terrorists and narcotics traffickers designated under programs that are not country-specific. Their assets are blocked and US persons are generally prohibited from dealing with them*. Importantly, OFAC adopts a “50 percent rule” pursuant to which an entity that is owned 50 percent or more by an SDN or multiple SDNs is also considered blocked even if not individually named on the SDN list. OFAC also has a search tool that can be used to screen names, though the tool does not address 50 percent ownership issues.

* “Blocking an asset” means that any property and interests in property in the United States that enter the United States (tangibly and intangibly), or that are or come within the possession or control of a US person may not be transferred, paid, exported, withdrawn, or otherwise dealt in.

Generally speaking, OFAC “primary” sanctions apply to US persons, meaning US citizens/permanent residents and US entities. However, certain sanctions programs extend jurisdiction extraterritorially. For example, OFAC’s Iran sanctions program prohibits foreign subsidiaries of US companies from engaging in activities that would be prohibited for the US parent to perform itself.

OFAC also exercises jurisdiction over the US financial systems. US banks (and their overseas branches) are therefore subject to US sanctions when processing transactions. Moreover, US intermediary banks clearing US dollar funds transfers through the United States are also subject to sanctions.

Extraterritoriality and blocking statutes

As noted above, “primary” sanctions apply to activities occurring within OFAC’s jurisdiction. Sanctions imposed for activity occurring outside of US jurisdiction are known as “secondary sanctions.” With secondary sanctions, the US government is attempting to use sanctions to pressure those outside US jurisdiction to act in line with US policy goals. Secondary sanctions are not automatic. Thus, a non-US company may be exposed to the risk of sanctions through certain activities, but those activities do not automatically violate US law, which happens under primary sanctions.

The United States maintains a variety of secondary sanctions based on a patchwork of numerous statutes, executive orders, etc. Secondary sanctions can be applied to a number of different activities involving sanctioned parties and/or sanctioned countries, such as Iran, Russia, North Korea, etc.

As a countermeasure, the European Union passed legislation referred to as the “Blocking Statute.” The purpose of the EU Blocking Statute (Council Regulation (EC) No 2271/96) is to protect EU companies from the extraterritorial application of third-country laws. The European Union does not recognize the extraterritorial application of laws adopted by third countries and considers such effects to be contrary to international law. These regulations essentially ban EU member states from complying or assisting the United States in enforcing the restrictions imposed under specified sanctions (currently consisting of US sanctions against Cuba and Iran). The Blocking Statute requires companies incorporated in EU member states to:

- Notify the European Commission whenever their economic or financial interests are affected directly or indirectly by the extraterritorial application of specified sanctions;

- Not comply with the extraterritorial effects of those sanctions; and

- Not enforce, within the European Union, any foreign court judgments or decisions of administrative bodies, such as OFAC, based on specified sanctions.

These regulations also allow EU member states to impose sanctions when there is a breach of the EU’s Blocking Statute. This means that effectively a company can find itself in the crosshairs of US and EU authorities, fined by one or the other, regardless of whose laws the company chooses to follow. In such instances, if the company can show that the non-compliance with specified sanctions would seriously damage its interests or interests of the European Union, it can apply to the EU Commission for an authorization to comply with US sanctions laws. Such an authorization may be granted by the EU Commission in specific circumstances as a derogation from this statute.

Licenses — Exemptions and exceptions

Most sanctions regimes include a licensing program. There are general and specific licenses. A general license serves as an exemption in that it is available to all persons and it authorizes the performance of certain categories of transactions without having to obtain approval from the licensing agencies beforehand. Alternatively, a person can apply for and request a specific license. A specific license is a written authorization from a regulator permitting certain activities. It may be issued on a case-by-case basis under certain limited circumstances and conditions. A specific license is not transferable.

Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS)

BIS is an agency within the US Department of Commerce that is responsible for administering the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) that apply to hardware, software, and technology. The EAR applies to exports and re-exports of all items subject to the EAR, whether involving a US person or a non-US person. Items subject to the EAR include:

- Items being exported from the United States,

- US-origin items wherever located, and

- Certain foreign-made items such as those incorporating more than a de minimis amount of US-origin controlled content and those that are a “direct product” of certain controlled US-origin software or technology.

It is therefore important for both US and foreign entities to understand whether products (as well as related software or technology) are subject to US export controls.

Distinct from the SDN list, BIS maintains the Entity List that imposes an export license requirement on exports or re-exports of items subject to the EAR to a listed person. It also maintains the Denied Persons List, which is a list of persons for whom export privileges have been denied.

The US government maintains a Consolidated Screening List that is publicly available and searchable. This list combines multiple screening lists from the US Departments of Treasury, Commerce, and State, including the SDN List, Entity List, Denied Persons List, etc.

Consequences for noncompliance

Sanctions and export controls are generally applied on a strict liability basis so that even if an organization did not intend to violate the rules nor knowingly violate them, it can be held liable for it. Noncompliance can result in civil penalties and criminal punishments, including prison. The United States has been most aggressive in its enforcement of penalties and the resulting fines. In response to a violation of US sanctions, OFAC may take no action, or may take a number of actions, including issuing a caution, imposing a civil penalty, and even referring a case for criminal prosecution. OFAC uses its enforcement guidelines as the method for determining whether additional investigation is merited, whether there should be a civil penalty, and if so, what the amount of the civil penalty should be.

The severity (or amount) of the fine is based on a number of factors. An important consideration is whether parties voluntarily self-disclosed the apparent violation of OFAC, which will result in a significant reduction in potential penalties. In addition, OFAC considers the following factors:

- Whether the violation involved willful or reckless conduct,

- Whether the management was involved in the violation,

- Whether the violator cooperated with OFAC’s investigation,

- The harm the violation caused to the sanctions program objectives,

- Whether the violator had a sanctions compliance program in place,

- How sophisticated the program is, and

- What, if any, remedial measures were taken to address the issue and prevent its recurrence.

How to assess a proposed business opportunity?

A threshold issue in analyzing any proposed business opportunity for sanctions and/or export control concerns is whether the activity is subject to US jurisdiction.

From a sanctions perspective, you must consider whether the activity involves a US person, including:

- US persons who may “facilitate” the business such as by providing insurance, transportation, or other incidental activities;

- US citizens/permanent residents in the company who may be involved;

- The US parent company’s role, if any, in the business activity; and

- US financial institutions who are either originator or beneficiary banks, or intermediary banks that may process US dollar funds.

Sanctions and export controls are generally applied on a strict liability basis so that even if an organization did not intend to violate the rules nor knowingly violate them, it can be held liable for it.

Even if no US persons are involved, you must also consider the applicable sanctions program. In the Iran sanctions example, a foreign subsidiary of a US company would be subject to the same restrictions as its parent. This means that transactions by a European subsidiary of a US parent company would need to be analyzed as if the activity was being conducted by a US person.

Export control restrictions raise a separate question regarding the goods being sold into a sanctioned territory, as well as any additional technical support, repairs, etc. This would include not only confirming whether products being shipped originate in the United States, but also understanding whether they incorporate US-origin content or are a direct product of US software or technology.

Once these jurisdictional elements are considered, companies should evaluate transactions on a case-by-case basis. This includes determining whether the activity is actually prohibited by sanctions or whether it might be exempt from sanctions or authorized by a general license. If not, then further consideration is needed to assess whether it might be possible to obtain a specific license. In our example, an OFAC general license authorizes the export of certain medicine and medical devices subject to strict conditions and restrictions. Careful examination of the general license is needed to assess whether a proposed business opportunity might be authorized by general license.

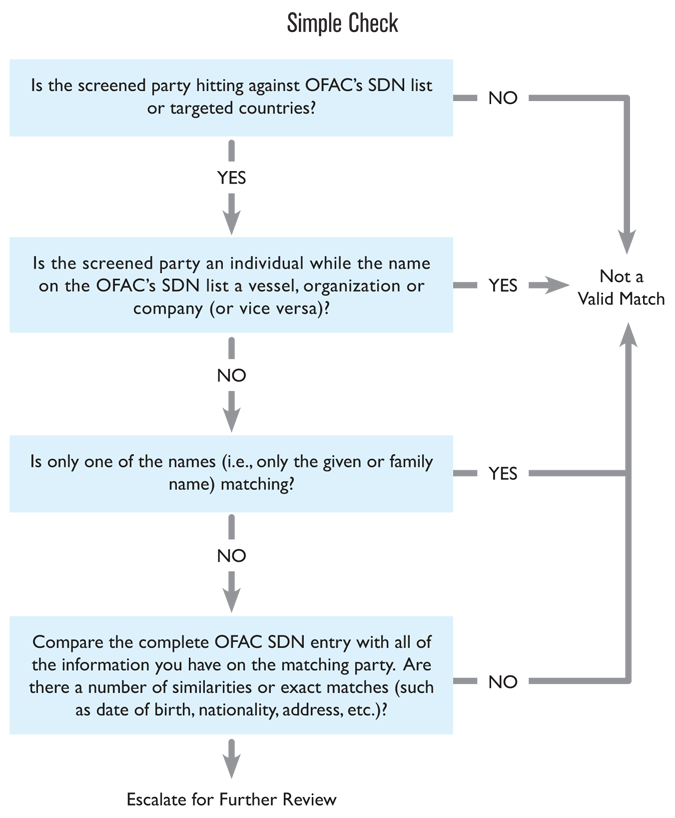

Furthermore, screening is a key element of any sanctions compliance program. Many companies use third-party vendors that provide software to screen customers, suppliers, resellers, and other third parties against relevant sanctions and export controls lists. It is also important to obtain shareholder information so that the owners of potential business partners can be screened as well.

The opportunity should also be evaluated against the backdrop of potential secondary sanctions. For example, sales of non-sensitive medical devices may not raise a red flag unless the transaction involves a sanctioned party. However, other sectors are likely to give rise to potential secondary sanctions considerations. This includes areas such as energy, transportation, insurance, finance, etc.

OFAC sanctions compliance guidance

Overall, companies should develop a sanctions compliance program to help manage these issues. In May 2019, OFAC published a recommended framework outlining essential components of a sanctions compliance program. These components are: (1) senior management commitment, (2) risk assessment, (3) internal controls, (4) testing and auditing, and (5) training. Each is briefly summarized below.

Senior management commitment

The board and senior management need to communicate their commitment to compliance by: (a) openly voicing and demonstrating their commitment to ethical values and integrity, (b) ensuring that their employees also embrace these values and that their commitment flows through all service areas and lines of business and (c) holding responsible those parties who are accountable for compliance (both full-time employees in compliance and those employees engaged in business).

Risk assessment

The company should conduct an OFAC risk assessment in a manner and with a frequency that accounts for the potential risks. The assessment should have the proper methodology to identify, analyze, and address risks that may be posed by customers, products, services, supply chain, third-party intermediaries, geographic location, etc. OFAC states that the risk assessment should then inform the level of due diligence to be performed at various points in the transaction life cycle.

Internal controls

The company should have effective and robust internal controls in place that outline clear expectations, define appropriate procedures, and minimize risks identified by the organization’s risk assessment. Written policies and procedures should be easy to follow, consistent with day-to-day operations, and communicated to all employees and any third parties that perform sanctions compliance responsibilities on behalf of the organization. Controls should be enforced through internal and/or external audits and prompt action taken to identify and remediate the root cause of any identified issues.

Sanctions change rapidly and changes are effective immediately — an effective sanctions compliance program should also have controls in place to respond quickly to changes in sanctions, including the addition of individuals/entities to the SDN list and modifications to any country-based sanctions programs.

Testing and auditing

Establishing a sanctions compliance program and putting it into motion is not enough. The program must then be monitored and evaluated. Audits assess the effectiveness of current processes and identify any inconsistencies between the policies and day-to-day operations with a goal of rectifying any weaknesses or deficiencies that are identified. The audit must be independent (i.e., performed by people who are not involved with the organization’s compliance staff) and performed by those sufficiently qualified to do so. The individuals who conduct the audit should report directly to the board of directors or a designated board committee. All audit recommendations for corrective action should identify the target date for completion and the personnel responsible for completing it and its progress must be tracked. Failure to properly address audit issues is a frequent criticism in cases in which regulators levy fines.

Training

The training program should provide customized, role-specific advice, delivered in easily accessible resources and materials, and be offered to all employees (stakeholders as may be appropriate). It should also include assessments to hold employees accountable for sanctions compliance.

Training topics can include: general background and history pertaining to sanctions, legal framework of what sanctions apply to the business and its employees, penalties for noncompliance, internal policies and procedures, review of the internal sanctions risk assessment, legal record-keeping requirements, reporting requirements, duties and accountability of employees, real-life sanctions evasion schemes, nature of products and service offered, how they work, and their associated red flags, etc.

A company’s training should be ongoing and provided on a regular schedule (at a minimum annually). Situations though may arise that may demand an immediate session such as after an examination or audit that uncovers sanctions compliance deficiencies.

Conclusion

US sanctions and export controls can often raise complex issues requiring an in-depth examination of all aspects of a proposed opportunity. This includes the entities involved on behalf of the business, the customer and related third parties, the products/services involved, and the use of the US financial system.

In-house counsel would be wise to ensure an appropriate risk-based OFAC sanctions compliance program is in place so that opportunities can be properly evaluated prior to engagement.

ACC EXTRAS ON… Challenges to global business

ACC Docket

Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions: Transaction Challenges in Emerging Nations (June 2019).

Globalization Continues to Create Increased Obligations for US Companies (Nov. 2018).

Primer

International Comparative Legal Guide to Sanctions 2020, First Edition (Dec. 2019).