CHEAT SHEET

- A poor substitute. Managers will often opt for a performance review they deem to be “negative” instead of following more appropriate and effective disciplinary action.

- Forget the numbers. Scores on the table will dictate the conversation and turn it into a line-by-line rebuttal or justification rather than an honest appraisal.

- Stay the course. Don’t do away with performance reviews entirely, as they are a necessary tool — just adjust them to better suit your needs.

- A modest proposal. Separate the performance review discussion from the performance assessment process.

The annual performance review process is both a time-honored and dreaded part of the business cycle. For many managers, the requirement is onerous, time-consuming, unnecessarily formulaic, and process-driven. It is viewed as a burden rather than as a productive part of staff management. Research conducted by CEB (a management research firm formerly known as the Corporate Executive Board) indicates that nine out of 10 managers are dissatisfied with their performance review process; and most managers and HR professionals believe that the annual review system has little correlation to actual business results. Many managers do a poor job of drafting reviews and frequently inflate scores and sugarcoat comments, which is often worse than having no reviews at all.

For employees, the process is often filled with anxiety or viewed as irrelevant and a waste of time. In a 2009 Reuters survey, 80 percent of employees were dissatisfied with their performance evaluation process. Researchers have found that the traditional annual review process “is ineffective at boosting performance, actively alienates employees, is based on a flawed understanding of human motivation, and is often arbitrary and biased.” Even the knowledge that a year-end performance review is on the horizon may damage daily communication with managers and coworkers. In a world filled with immediate gratification and constant electronic communication, the once-per-year evaluation process is a dinosaur.

Meanwhile, any employment lawyer will tell you that employee performance review documents are frequently detrimental to the company’s legal case in employment-related litigations, while seldom providing helpful information that is not available from other sources.

And yet, most major companies continue to spend significant time and money on the performance review cycle each year. One estimate puts the costs of a traditional performance review system at about US$3.5 million per 1,000 employees. Recently, some major companies including Microsoft, Accenture, and GAP have begun moving away from the traditional review process. Even General Electric, a pioneer of the “rank and yank” system of strict numeric performance evaluations, has traded it in for a smart-phone app that gives immediate feedback to employees about their work. But, according to recent data, less than 10 percent of Fortune 500 companies have abandoned the traditional annual performance ranking process. It is still ubiquitous at most companies both large and small, despite the general dissatisfaction with the system by both employees and managers.

In the old GE system, the bottom ten percent of rankings were presumptively fired, hence the term “rank and yank.”

For HR heads and in-house employment counsel, any desire to fix a broken system requires a viable alternative, since the complete abandonment of all performance evaluations is not an attractive solution. This article suggests an alternate process that replaces the annual performance review form with a two-step process of regular discussions between managers and their subordinates and a separate, confidential written staff assessment memo addressed to higher management. By removing the numerical score sheet from the performance management discussion, managers can be more constructive and forward-looking in their meetings with employees. And by removing the employee conversation from the evaluation process, managers can be more honest and objective in their report of actual performance to their bosses. This system would ameliorate many of the deficiencies that plague the traditional performance review process.

What’s wrong with the traditional process?

Like an old, comfortable shoe that you can’t bear to throw away no matter how ragged and full of holes, the performance review process is often a legacy decades in the making. Most people started out in their working lives at companies that had annual performance reviews, and have worked mostly at companies with similar processes. There is an expectation that any “good” company will have a performance review system. This notion is reinforced by dozens of vendors marketing the latest and greatest systems to make the performance review process easier, faster, and allegedly more efficient. However, HR professionals and employment lawyers have no difficulty identifying a number of glaring deficiencies that are present in most systems, including the following:

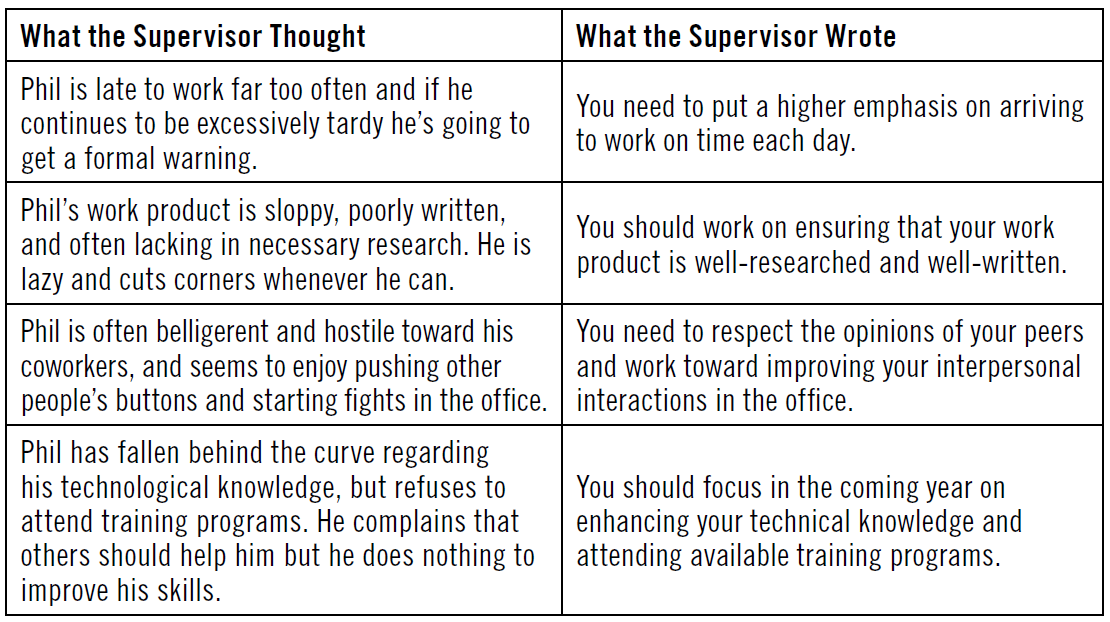

Managers want to be “positive.” Managers are often taught to use positive reinforcement as their model for motivating employees toward superior performance. Even in training for how to conduct a performance review, most trainers will suggest leading off with positive comments and ending with positive comments. But, this tendency toward positive results is the most common flaw in annual performance review documents — line managers are often too easy on the employees with whom they will shortly sit down to discuss the evaluation. In an effort to avoid conflict, managers will often give everyone a “satisfactory” ranking. The apprehension that most people have about confronting another person (even a subordinate) with negative commentary is very real. The result is often language that is intended to soften the blow, and make the resulting conversation easier to have. Consider these examples:

There is nothing inaccurate about the comments the supervisor wrote in the review, but the tone and language downplay the significance of the issues. Such softened comments are frequently accompanied by inflated numeric scores corresponding to a “satisfactory” or “average” assessment. On the witness stand, the supervisor could explain what she really meant, but on the face of the document, Phil’s problems don’t come through. Companies have even been forced to assert in court that their performance review forms were meaningless in order to overcome the impact of a manager’s positive comments about a laid off employee. Frequently, positive rankings on performance reviews block a company from succeeding on a motion for summary judgment.

Managers will substitute a performance review they deem to be “negative” for more appropriate and effective disciplinary action. Line supervisors often tend to avoid confrontational and difficult conversations with their subordinates. Since the manager knows that she will be forced to have that one annual performance review conversation, some managers will use that as the one and only time that they speak with an employee about their job performance problems. The manager (wrongly) thinks that the written performance review, if sufficiently negative, serves the same function as a performance warning and fails to more properly document the deficiencies. But, courts and arbitrators will seldom agree that a negative rating on an annual review is a suitable substitute for progressive discipline. If the company lacks good alternative evidence of poor performance, the line supervisor has not done her job properly.

Company-wide forms make it difficult to evaluate employees based on their specific job duties and responsibilities. One of the elements missing from most company-wide systems is a specific linkage between the employee’s job duties and the elements of the performance evaluation. Rather than trying to evaluate everyone on vague criteria like “communication skills” or “ability to drive change,” a truly valuable evaluation needs to be linked to the actual skills, tasks, and duties of each employee.

Annual reviews tend to be backward-looking rather than forward-looking. In most cases, an annual performance evaluation form provides ratings for how the employee performed over the past year. But, instead of focusing on what the employee has done wrong or right over the past year, the best annual performance discussions focus on the upcoming year and what the employee can/should do to improve and become more valuable. Rehashing months-old problems is not typically the basis for a constructive conversation about the future. And, of course, some managers will neglect their obligation to have frequent feedback sessions with staff and leave all feedback to that one annual meeting. Some writers have speculated that the current crop of “millennials” crave and expect feedback more frequently than even those in Generations X and Y. The Twitter/Facebook/Instagram generation is accustomed to instant responses. Any successful performance development program, therefore, requires that employees get feedback — both critical and constructive — as often as possible.

Managers don’t invest the time needed to actually do a good job, which results in a shoddy document. Another reason that performance review documents are often lacking is that creating a truly good one takes time, effort, and training. In order to really identify the areas of concern and write a meaningful review, the line supervisor will need to consult documents and emails from the past year, consult with coworkers and clients, and spend some real time in the drafting. None of this is likely for the average harried supervisor with more important things to do. The goal becomes the completion of the process and checking off the “done” box, rather than seriously focusing on the future development of each employee.

The scores on the sheet detract from the conversation. If there is a written document on the table during an in-person meeting to discuss the employee’s performance, goals, and development, many employees will focus entirely on the document and its contents and not on the more important content in a face-to-face conversation with their manager. People naturally become defensive when faced with written criticism and “unsatisfactory” ratings, and tend to want to contest or question individual line items where they perceive unfairness or inaccuracy; turning the conversation into a detailed review of the document, rather than a general discussion of goals and paths to improvement. Even managers, regardless of training, will tend to use the document as a crutch and spend the meeting going through the document rather than focusing on broader issues. And afterwards, some employees will expend tremendous time and energy writing copious rebuttals rather than working on job training or other performance improvement.

Senior managers seldom look at the reviews other than to check the box that a review happened. HR consultants will tell you that part of a good performance appraisal process involves a more senior manager scrutinizing the line supervisor’s reviews in order to: (1) ensure accuracy and appropriate level of detail; (2) ensure that there is consistency across the manager’s organization as far as numeric scores and proper commentary about poor performers; and (3) ensure that proper performance management or disciplinary action occurs after the review regarding poor performers. If the exercise is one of box-checking such that senior management is satisfied merely by the fact that performance reviews “happened,” then a key value of the process is lost.

Should we all abandon performance evaluation systems entirely?

The total abandonment of employee evaluations is not a solution to the problem. Even those companies that are trying to move away from formal numerically-based performance reviews are implementing alternatives so that employees receive appropriate feedback. One of the central goals of a performance evaluation program is to give managers a structure around which they can have conversations with employees that will help the employees improve and thrive. Feedback on work product and performance is an essential element of good management. But, such communication and feedback can, and should, exist entirely outside the formalistic structure of an annual performance evaluation.

There are, of course, other reasons for having written performance assessments, aside from using them during communications with employees, including:

- To document poor performance or superior performance in the event of a layoff.

- To document the performance level needed for merit-based pay increases or bonuses.

- To distinguish employees who should be considered for advancement or promotion.

- To provide senior management with information about the state of the workforce and potentially the need for changes in hiring strategy or training programs.

The question is whether these goals can and should be accomplished outside the four corners of an annual performance evaluation form.

A proposal: Separate the performance review discussion from the performance assessment process

All of the above-listed deficiencies in the traditional performance review process can be blamed to some extent on the document — the loathsome performance review form — and the numbers or rankings it contains. While it is necessary for the organization to have a written record of the manager’s evaluation of the staff’s job performance, if the individual employee document could be eliminated from the process, managers could have forward-looking conversations with their staff, focused on goals, future projects, and ways that performance can be improved, rather than focusing on the past year and the contents of the form. Managers could provide positive reinforcement during discussions, without needing to sugarcoat negative comments on the form or inflate rating scores.

The manager’s honest assessment of job performance would be better presented to senior management as a summary of the entire staff, broken down by job classification and tied to the specific duties of each group of employees. This type of assessment would also give senior management a comprehensive view of the entire group, rather than having to rely on the cumulative scores from separate evaluation forms. Therefore, for many organizations, a better process would be to create a two-step employee development, management, and assessment process.

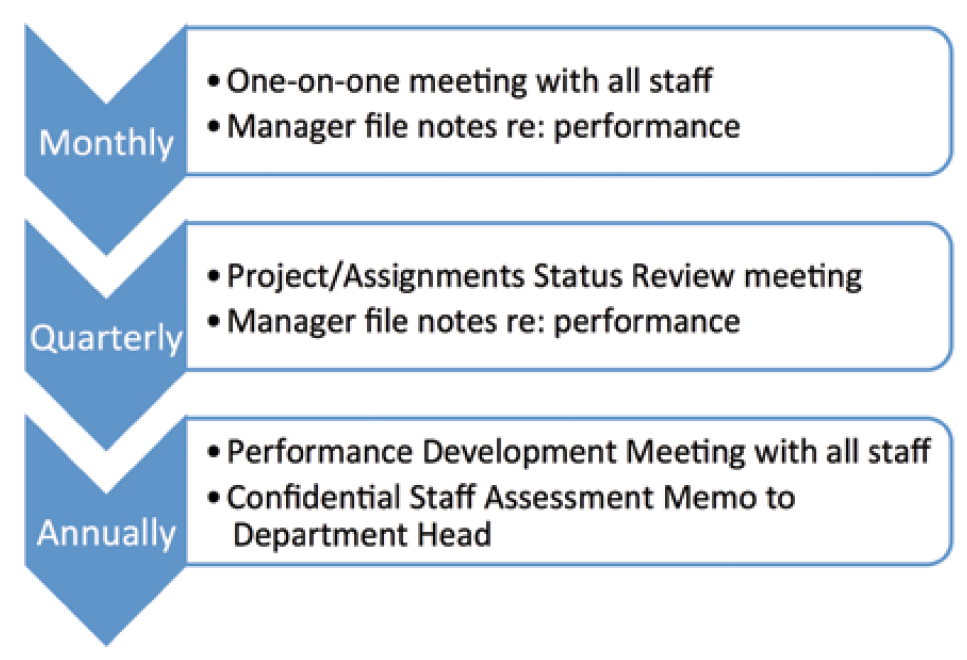

Step 1 – Employee development and management meetings

Part one of this process is communication between line managers and their staff. This is the process for providing feedback to employees about their work, their goals, their career advancement, and their need for training. Managers should meet with employees one-on-one frequently — ideally weekly or monthly, but at least quarterly — to have a two-way discussion of how the employee is doing, whether the employee perceives any problems or need for training, what the employee’s short-term and long-term goals and projects are, and for the supervisor to give feedback on recent performance. These should be informal discussions, without the structure of a pre-populated set of points to cover. Employees should be encouraged to pitch ideas, ask for training, ask to be assigned to particular projects or types of work, and let their manager know what their aspirations are for advancement. In this context, managers can freely follow a positive reinforcement model and focus on what the employee is doing right. But, if there are performance deficiencies that need to be addressed, the manager can tackle them early. And even if there are Apps or emails to provide instant feedback, there is no substitute for face-to-face meetings.

At year-end, when the manager is already meeting with the employee to announce upcoming salary increases and/or bonus payments, there can be a look-back and a year-ahead projection for all these issues. Here, the manager identifies the employee’s accomplishments, identifies areas that could stand some improvement, and sets out a program for the upcoming year calculated to make the employee more successful. In appropriate contexts, this process can start with a self-evaluation and a self-generated list of accomplishments and areas where the employee would like more training or would like to improve or expand.

The key here is that these meetings, including the year-end meeting, are not accompanied by any written document or any numerical scoring. The employee need not focus on what the supervisor has written, and can focus on the conversation. There is no need for a rebuttal, and there is no document placed in the personnel file. If appropriate, the manager might follow-up with an email summarizing expectations or listing upcoming goals or training, but neither the employee nor the manager need to be focused on the contents of a review form during the discussion.

By fostering better and more frequent communication, this process allows managers to have “development” discussions with employees that are not limited to a numerical evaluation of past performance. Issues of performance deficiencies may, of course, come up, but there are other contexts where “performance management” is more appropriate. Taking the “review” out of the meeting lessens the pressure on both the manager and the employee, and taking away the review form and a numerical score removes the elephant in the room and allows both parties to focus on something other than the written statements on the documents.

If the employee’s performance is unsatisfactory, the manager must document that separately in a warning memo or a memo to the file that an oral warning was delivered. This should happen in any system, but the absence of a written performance review form will force line managers to properly document poor job performance by other means. While an informal performance development and management conversation may include comments about recent performance problems, the meetings should not be seen as disciplinary meetings. (In a union-represented environment, management must make clear that such meetings are not part of the disciplinary process, lest the employee exercise Weingarten rights and demand to have a union representative present). The progressive discipline process must be separate from these development and management meetings. (See sidebar below regarding how to properly maintain electronic and paper records on employee performance).

This process forces managers to talk to their employees by taking away the crutch of the annual performance review form.

Maintaining electronic personnel files

In the process of preparing for a performance review discussion with an employee, the line supervisor should be reviewing records related to an employee’s assignments, deadlines, submissions, corrections, job metrics, sales, attendance, and other merits of work performance. Managers may keep these kinds of records in different places, including emails. When gathering records in advance of a development and management meeting, the supervisor has an opportunity to archive these records to an electronic “personnel file.” During the year, the supervisor should also “file” electronic documents and emails into an employee file location for future reference.

Before the advent of electronic information storage and email, a manager would have a physical file folder in a drawer into which he or she would drop each new document as it was created in hard copy. The physical file would be passed along to the next manager if the supervisor moved on, or if the employee moved to another department. When a union or the EEOC asked for a copy of “the employment file” it was relatively easy to pull out the folder and copy the file.

Now, more and more, supervisors are storing records (if at all) in electronic form, which makes it easier to hold more and larger documents, but which also makes it easier to lose records when managers leave or employees move to new departments, and makes it more difficult in some cases to identify and retrieve the “file.”

In training supervisors about what to hold onto and how to store it, these are the important points:

WHAT RECORDS TO HOLD ON TO

- Performance reviews

- Formal disciplinary notices (written warnings and notes regarding oral warnings)

- Records of informal discussions about job performance or behavior issues:

- Emails concerning attendance/lateness issues

- Emails concerning work issues, late assignments, conflicts with other employees, performance expectations or standards, etc.

- Handwritten notes of any meetings concerning performance issues

- Copies of work product that was unsatisfactory, required correction or re-submission

- Copies of calendars or other records of appointments and activities

- Sales records or other objective measures of productivity (along with comparative information for other similarly situated employees)

- Notices about promotions, transfers, changes of assignments, etc.

- Commendations, positive feedback from customers, or internal clients

- Complaints from customers or internal clients

- Attendance records

- Notes from the manager about incidents in the office, thoughts, evaluations, etc – to be used as part of preparation of performance review, but which are not part of formal disciplinary notices

- Employee complaints about work environment, assignments, coworkers, harassment, discrimination, unfair treatment, etc. – and any responses from the manager

- Requests for accommodations for religious, medical, disability, or family reasons, and any responses from the manager

HOW TO STORE RECORDS

- Hard copy (preferred). Print out copies of all above documents and place them in a physical file. Maintain a physical file on all employees who report to you. If there are electronically stored files that are too bulky to print and store in hard copy, print out the first page of the document and place just that page in the physical file along with a notation of the file location where the electronic copy of the entire document can be located.

- Electronic files

- For Microsoft Office documents (Word, Excel, Powerpoint, etc.) or other documents in formats that can be stored on the company’s servers, create a PRIVATE file folder called “Employee Files” or “Personnel Files” and in that folder create an individual folder for each employee who reports to you. Create a “cover” sheet for the file, tacked to the top of the file list, containing contact information for the employee and basic employment information (hire date, salary, wage increase history, etc.). All other documents can be placed in the folder raw, or organized into sub-folders.

- When the manager leaves the position, he/she must copy those electronic files onto a portable drive that can be given to the next manager, or into a holding file on the corporate server accessible by the new manager.

- When the employee moves on to another position within the Company, the supervisor should copy the entire folder onto a portable drive and give it to the new manager.

- When the employee leaves the company, the manager should copy the file and send it to HR for permanent storage with the employee’s personnel file.

- For email

- The supervisor should copy their human resources generalist (HRG) on all emails that involve performance issues or disciplinary action so that the HRG can maintain a separate email folder/file for that particular employee and create a kind of “backup” file.

- The supervisor should create an Archive folder on his/her corporate server (not within the email system) for each employee.

- The supervisor should copy into the employee’s folder any emails concerning any of the topics listed above, along with attachments.

- When the manager or the employee changes jobs, or if the employee leaves the company, the supervisor should copy the files and transfer them to the next manager or to HR as specified above.

- Annual back-up of all files. Annually, at the time of the employee’s performance management discussion, managers should copy the entire contents of their electronic personnel file and send a copy to their HRG, so that HR can maintain a copy of the file as a backup. (This back-up process can occur more frequently, at the manager’s discretion.)

- For Microsoft Office documents (Word, Excel, Powerpoint, etc.) or other documents in formats that can be stored on the company’s servers, create a PRIVATE file folder called “Employee Files” or “Personnel Files” and in that folder create an individual folder for each employee who reports to you. Create a “cover” sheet for the file, tacked to the top of the file list, containing contact information for the employee and basic employment information (hire date, salary, wage increase history, etc.). All other documents can be placed in the folder raw, or organized into sub-folders.

Step 2 – The confidential performance assessment memo

Part two of the process is for the manager to create a written performance assessment for all the employees under that manager’s direction. The Confidential Performance Assessment (CPA) memo goes only to the manager’s boss — not to the employees. This is the written record of the supervisor’s evaluation of each employee's performance. Although this assessment could use numeric indicators, it is probably best not to. Rather than establishing across-the-board criteria against which all employees are scored, the assessment memo should evaluate each person against his or her own tasks and responsibilities. All employees in the same job title should be evaluated against the same set of criteria, linked to the specific duties of that job. This will require the company to have a job description for each job that is accurate and lists the essential functions, which is extremely useful when conducting force reductions or when addressing ADA/accommodation claims.

If the company does not want the line mangers to rank their staff within job classifications, then the employees can be listed alphabetically or by seniority. The commentary about each employee's performance will indicate their relative performance within the group, which will be helpful in the company’s later internal assessments and in litigation. Or, the company may choose to force managers to rank employees in the same job classification from best to least best — which does not necessarily imply that the employees at the bottom of the rankings are poor performers.

The CPA memo includes a record of each employee's performance. But, by freeing the manager from having to face off with the employee and justify or explain the manager's evaluation comments, managers almost certainly will be more honest and accurate in their assessments. There will be no need to tone down the comments or to inflate the ratings. Of course, if the CPA memo rates a terminated employee higher than others who were not discharged, then the company may have a problem, but not more so than if the same information were contained in traditional performance review forms.

Also, in the event of litigation, the manager’s comments about any individual employee will be contained not in a stand-alone document, but rather in a staff assessment memo that includes commentary about the employee’s peers, which will put the manager's words in full context, and which may even include the relative rankings of all employees in the group. This will eliminate the problem of a performance review form — standing alone and out of context — being used to contradict the company’s position in litigation that the employee was a poor performer relative to the group.

The CPA Memo will also be far more valuable to senior management, and will foster actual review by higher level managers. Senior managers will have a one-stop summary of the performance of the entire group, rather than a series of hard-to-read evaluation forms or a summary of statistical information based on review form scores. This format will foster greater scrutiny of the relevant information by the senior managers, and will provide a more accurate view of the overall and relative performance of the workforce. Senior managers will more easily see from commentary about merely adequate or below-average performers in a group that the entire group may be a problem and need training, personnel changes, or perhaps a new manager. This information is often hard to glean from a series of “satisfactory” ratings on traditional review forms. This scrutiny can also root out manager bias and ensure that the line manager’s evaluation is objectively fair.

The CPA memo process will also force line managers to do their homework — review productivity reports, sales records, and other documents that will back up the comments about the group in the CPA memo. Simply cutting and pasting last year’s review comments and checking off a bunch of score boxes will not cut it. And, the CPA memo will provide a better context in which to evaluate the line manager’s performance in completing his staff evaluations. A shoddy CPA memo will stand out much more than a series of poorly drafted annual review forms, and if the details about a particular employee are missing or incomplete, the reviewing manager will more easily spot the problem.

In most respects, this process would be superior to the traditional written review form system.

Other factors to consider. There are, of course, potential problems with any performance review system, and the proposed CPA memo process will not create utopian perfection overnight. You should consider the pros and cons of any process as it applies to your own organization.

One potential issue is the very fact that employees will not see what is written about them in the confidential staff assessment memo. Employees will be aware of the existence of the group assessment memos, and will wonder what was written about them. It will be best to maintain the assessment memos as confidential management documents, and line mangers should be instructed to say that the memo is confidential rather than giving out vague or incorrect information about its contents. In a properly run system, the manager should be able to say to any of her direct reports: “There is nothing in the confidential memo that we haven’t spoken about together during our one-on-one meetings.” Line managers must be held accountable not just to have one meeting with each employee annually, but to actually maintain a constant flow of information by having regular meetings to discuss work, goals, and performance.

In the event that the assessment memo is disclosed to employees (e.g., in litigation), the contents should be accurate and the line manager should be able to stand behind any comments, just as she would for a traditional performance review form. There is always some chance that the manager’s oral comments to an employee will be inconsistent with the written CPA memo, but in most cases the employer will be better able to deal with that kind of inconsistency than when there is a written company document (the performance review form) where the manager’s inaccurate comments are officially recorded.

There may be some fear that employees will focus on the “mystery” of what their manager wrote about them, but the reality is that managers draft emails and memos to their bosses all the time regarding employee behavior and performance that are not shared with the employees. Over time, the process will become ordinary and the mystery will lose its allure. For union-represented employers, negotiation with the union or works council may be a good idea, to set the boundaries of when the confidential staff assessment memos can and can’t be obtained and shared.

And, of course, the confidential assessment memo will be subject to discovery during litigation, just like performance reviews. But, by evaluating all the employees in a work group together, there will be greater context for any comments. Even if there is still a tendency toward score inflation, a plaintiff ’s attorney will not be able to present an official company document containing comments that the employee’s performance was “satisfactory” without also including the comments from the same manager that all the peer employees were “excellent” and “superior.” The company will be able to use the comparative comments about the other employees to its advantage without the need to introduce separate performance review forms for all similarly situated employees.

It is not clear whether the confidential staff evaluation memo would be considered part of an employee's “personnel file” for purposes of state laws that allow employees to have access to those files. Best practice here would be to not include copies of the confidential memos in any individual employee's “file” and rather have the manager keep them in a separate file of staff evaluations. While certainly subject to discovery in litigation, a plaintiff ’s lawyer will need to ask for the CPA memo specifically, and employees would not routinely be granted access.

Managers will still need to properly document employee performance deficiencies outside the confidential assessment memo. Employees have a right to know if their performance is lacking and should be given an opportunity to correct the issues. Putting negative comments in the confidential assessment memo without separately giving an employee a performance warning will not suffice in most cases to document just cause for further disciplinary action. But, since managers know that the confidential memo is not shared with employees, they should be less likely to rely on it in this context than they would rely on a shared performance review in a traditional system.

Line managers will also need to have development and management conferences with their employees. Some managers, freed from the annual obligation to have a “performance review meeting” may abdicate altogether their responsibility to meet with and talk to their staff about their performance and development. Senior management may want to implement some tracking or monitoring process to ensure that their line managers are having the meetings with staff and not just preparing the CPA memo and considering the process finished. This is good practice regardless of what kind of performance review system you have in place, but it will be particularly critical in the absence of an annual review form.

And, line managers will still need to be trained about how to properly draft the group assessment memos. Higher-level managers must be trained in how to read them and use them, including sending them back for revision if the senior manager thinks that any of the comments are out of whack with the reality of the workplace. But, having one honest memo instead of a bunch of separate performance review forms to read should foster such critical review. Companies should not (ever) make employment decisions based on only one person's opinion or one annual evaluation, but having an honest and comparative assessment memo will be a good starting point when evaluating promotions or force reductions.

Note that it would be a bad idea to institute the CPA memo process while also maintaining a system of written and shared performance review forms. The likely inconsistencies between a written performance review form rating and the contents of the CPA memo would create internal contradictions within the company's own records, and would certainly be relied upon by plaintiff ’s lawyers to establish a disputed issue of fact. Such inconsistencies would subject the line manager to uncomfortable cross-examination and damage her credibility as a witness. (If checks were put in place to ensure that there were no inconsistencies between the documents, then the tendencies of line managers to sugar-coat comments and inflate ratings in the shared forms would only be duplicated in another written document, which will not help the company’s litigation position).

There are also ancillary processes that a company may currently merge into their automated performance review process, such as having employees click/sign an annual attestation of compliance with a code of conduct, compliance with the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, or acknowledgment of other corporate policies. Removing the written document from the performance review process would mean creating separate process for these other sign-offs.

On balance, the CPA memo process described here could well be a superior performance management and evaluation process for many companies.

Further Reading

The Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2008, Samuel A. Culbert, “Get Rid of the Performance Review.”

The Washington Post, “Why Big Business is falling out of love with the annual performance review,” Aug. 17, 2015, citing CEB data.

“Why Big Business is falling out of love with the annual performance review,” The Washington Post, August 7, 2015 (citing an analyst with the Institute for Corporate Productivity who fixes the number at about ten percent).

“Legal Guidelines for Associations for Conducting Employee Evaluations and Performance Appraisals,” Center for Association Leadership, May 2002 (M. Basin, Venable LLP).

EEOC v. Texas Instruments, Inc., 72 FEP Cases 980 (5th Cir. 1996).

Gerundo v. AT&T Inc,, 5:14-cv-05171 (E. D. PA. 2015) (judge denied summary judgment where plaintiff was at the bottom of performance rankings prepared before reduction in force, but years of prior positive performance reviews created issue of fact as to job performance).

See Barrett & Kernan, “Performance Appraisal and Terminations; A review of court decisions since Brito v. Zia with implications for personnel practices,” 40 Personnel Psychology, 489, 494 (1987) (citing cases where lack of upper management review allowed line manager “to act out his prejudice” and noting that courts “seem to look favorably on the use of a review system by upper-level personnel to prevent individual bias”).