CHEAT SHEET

- Develop your team. The in-house department’s status as a cost center impacts the training available to corporate lawyers, requiring creative legal development solutions for your team.

- Establish a management framework. The skills required to manage a team at a law firm differ from those in a managerial role at a corporation, so some self-reflection might be useful before making the switch.

- Learn to say no. Large law firms do not typically encourage denying client requests, yet in-house lawyers do have to deny internal business initiatives frequently.

- Advance the business objectives. In-house lawyers are engaged in all phases of business projects, and have a much greater scope to advise.

There have been a number of thoughtful articles written about the transition from law firm to in-house practice. Little attention, however, has been given to the infrequent occurrence of transitioning from law firm practice to an in-house management position, such as assistant general counsel or deputy general counsel. This article ventures beyond the technical legal skills, which were presumably developed through years of grueling work at a law firm, to focus on the leadership skills that must be leveraged to successfully transition to an in-house management position.

Many professionals in corporate America, lawyers and non-lawyers alike, find managing a team difficult. A law firm lawyer faces a more difficult transition to in-house management because the values that drive success at a law firm are very different from the values of a corporation. This article outlines important differences in the two organizations’ values and suggests a practical approach for successfully reconciling them to improve the chances of a successful transition.

Large law firms tend to be fairly flat organizations, normally comprised of non-lawyer support staff, associates, partners, management committee(s), and the managing partner. Due to the partnership structure of law firms, management responsibilities are normally delegated to formal or informal committees while practice group leaders handle certain administrative tasks. This structure contrasts with a large corporate organization, which organizes employees into teams and concentrates management responsibilities for each team to a single individual manager. Law firm partners (i.e., owners) rarely view good management of firm employees as essential to the bottom line of the firm or their compensation. Consequently, large law firms generally dedicate few resources to developing good management skills. In direct contrast, good management is absolutely essential to the success of a large business and businesses spend significant resources identifying and developing great managers.

To successfully meet the challenges of transitioning from a law firm lawyer to an in-house manager, focus must be given to five key areas: (1) leading a team; (2) how to best advance the company’s business objectives; (3) client satisfaction; (4) successfully navigating the organization’s unique culture; and (5) establishing the new manager’s leadership framework.

The active involvement and support of your manager is critical to your transition to in-house management. This article also identifies key opportunities for your manager to effectively help and support your successful transition to in-house management.

Your team

Value of team

Unlike most corporations, the structure of large law firms is not conducive to building and maintaining high functioning teams. Generally, large firms place enormous value on the relationships between a law firm partner and the client. Consequently, the law firm partners, credited with establishing and/or maintaining client relationships (i.e., rainmakers), typically receive the highest compensation and wield the most power at a firm. As such, most law firm lawyers are not incentivized to involve peers in client development, as doing so may mean such partners are forced to share client credits and, consequently, make less money. This “eat-what-you-kill” model discourages collaboration and forces partners to be territorial with client relationships, thereby rewarding behavior detrimental to teamwork. Additionally, the norms that have evolved in most large firms as a result of this “eat-what-you-kill” model, including (1) high turnover rates among attorneys, especially associates; (2) the “up or out policy,” that forces attorneys who fail to be elevated to partner out of the firm; and (3) a billable hour model that encourages attorneys to bill as much as possible and discourages socialization and mentoring, which further undermines teamwork and those management skills that maximize value.

As you transition from law firm practice to in-house management, your in-house legal team becomes your most valuable asset. As a manager in a corporate organization, you are ultimately responsible for your team’s success and failure, which, in turn, means you are responsible for the results of each member of your team. Your resume is really no longer yours alone, but reflects the results and accomplishments of your team. Thus, your success comes from a talented, diverse, and high-performing team that delivers great results and advances the business strategy and objectives.

Despite the challenge, a successful law firm attorney with strong leadership skills is nonetheless well equipped to take on management responsibilities and could bring a different and valuable perspective to an in-house legal department.

Assessing your talent

At most large law firms, formal and informal committees handle the hiring, termination, and promotion decisions. Although a single individual does not make the decisions around hiring and firing, each firm attorney’s success is partially dependent on his or her ability to quickly assess talent at the law firm. For example, junior associates learn to quickly identify and enlist the most talented paralegals to work on their matters. Similar assessments by firm attorneys occur at every level of a firm. Mid-level associates assess junior associates; senior associates assess mid-level and junior associates; partners assess senior associates and other partners. At a firm, attorneys quickly realize their success is partially dependent on identifying the best available talent to staff on matters.

In contrast, as an in-house manager you will receive significant control over personnel decisions, including who to hire, terminate, promote, and reward. A successful transition to in-house management requires you to leverage (1) the valuable talent assessment skills you developed during law firm practice and (2) the management tools offered by the company.

The first 90 days in your new role is an important time for you to conduct a thorough review of your team. Evaluate each person’s technical, leadership, and communication skills, as well as attitude, effectiveness, team role, prior results, and potential. Are there any other competencies important for your team to function at a high level? Develop a plan to address gaps if they exist. A healthy plan will likely include a mix of professional development opportunities, promotions, and personnel changes. Believing you can develop everyone to be superstars instead of making the difficult decision to let someone go is a frequent mistake of new managers. If personnel changes are required, those decisions should be made in your first 120 days. The ongoing development of talent, however, must remain a continuous priority.

Develop your team

After you are confident with your team’s talent, seek and create opportunities to develop members of your team. Aim to improve their technical, leadership and communication skills, and business acumen. For 200 years, law firms have developed the best training processes to produce highly skilled and technical lawyers. The training of lawyers is like the research and development departments for other businesses. Fortunately, you have been the beneficiary of law firm training and participated, knowingly or unknowingly, as both a student and teacher in developing technical legal skills. As a result, you will be very familiar and comfortable with training and developing lawyers and paraprofessionals.

At large law firms, practice groups typically create a training curriculum for new attorneys and hold regular training for experienced lawyers. Large firms often hold memberships with the local bar associations, which offer regular courses on a variety of legal topics. In addition, law firms themselves normally have many nationally recognized thought leaders in specific practice areas who host webinars or seminars, and prepare white papers and articles on various topics. However, the experiential learning that occurs when a senior lawyer works with a less experienced lawyer is the most effective training offered by, and woven into the culture of, all major law firms. This experiential learning includes both observational learning and learning-by-doing with the supervision of a more senior attorney. Typically, the law firm experiential learning process includes regular real-time feedback by the senior attorney, especially for associates. It often occurs through comments provided by the senior attorney on each piece of work product generated by the associate, or verbal corrections to non-written work. This sort of real time feedback is extremely valuable to the development of employees and, although sought in business organizations, business managers rarely provide it.

This prior experience and familiarity with training lawyers is an advantage that transitioning in-house legal managers have over lawyers who have been practicing in-house for most of their careers. Typically, in-house legal departments have limited resources, compared to large law firms, to train their lawyers. In addition, as corporate cost centers, in-house law departments seek to maximize efficiency and typically avoid staffing multiple in-house attorneys with the same specialization on a single matter, which limits experiential training opportunities for in-house lawyers. For example, my in-house legal team consists of eight lawyers, who are each highly specialized with very little overlap. Even where specialization overlaps exist, it is unusual for me to assign more than one of those attorneys to work on a matter jointly because of limited resources. Conversely, when I practiced in law firms, I was usually one of many attorneys with the same specialization. The firm often staffed each matter with a senior attorney and at least one junior lawyer.

Although resources may limit your ability to adopt the law firm training structure, a wide range of options remains available. To offer some experiential learning, I hold biweekly meetings among the attorneys with specialization overlap for the sole purpose of having them learn from and coach one another. A specialist explains the latest development on the subject and how she addressed the legal issues. The other attorneys ask questions and draw on past experience to offer coaching.

Paraprofessionals can be highly valuable to an in-house law department, if leveraged appropriately and if in-house counsel play an active role in their development. You have an opportunity to draw on your prior law firm experience to create an effective training and development program for in-house paraprofessionals. A paraprofessional training program should include experiential training gained from working with your team attorneys, including real-time feedback from those attorneys. In addition, to maximize the value of in-house paraprofessionals over time, I have found it valuable to work with each paraprofessional to create a development plan, provide the paraprofessionals with stretch assignments, and offer some of the same legal training opportunities offered to lawyers.

When developing in-house lawyers, I found it valuable to start by asking each attorney to prepare an initial draft of a development plan, which offered better insights into one’s desired career trajectory. Starting with the initial draft, I worked with the attorney to build out the development plan to include the skills and training that were valuable. Do not take this conversation lightly; it is important to convey that the manager has a vested interest in the success of the attorney.

Although internal resources for training lawyers may be limited, you will find valuable resources available to develop the technical legal skills through continuing legal education providers such as PLI, Practical Law, and local continuing legal education providers, such as MCLE, which offer courses, webinars, and training materials. In addition, law firms offer regular seminars/webinars on recent developments in the law.

In order to improve the business acumen of attorneys on your team, require each of your attorneys to attend at least one industry (non-law) conference (to the extent you have room in your budget). By attending an industry conference, the lawyers will better understand the business, its challenges and opportunities, and it will put them in a position to offer more proactive legal advice. Local bar associations, law firm webinars and seminars, and conferences free to in-house counsel all offer development opportunities for very little money.

Advance the business objectives

In-house management allows more enhanced visibility into the business, especially as it relates to the company’s strategic priorities and business plan. Law firm lawyers are often engaged on a project well after it is underway, thus missing key background information and analysis leading up to the engagement. The business typically seeks advice from in-house lawyers before spending significant resources on a project at the “idea” or exploration phase of the project. During this phase, the in-house lawyer participates in discussions around the strategic rationale, desired outcome, potential barriers and risks, and alternative ideas. Enhanced visibility provides the in-house lawyer far greater opportunities to provide proactive legal advice, and connect the dots when counseling internal business clients (This article refers to a corporation’s internal business units as the “clients” of in-house counsel. However, such reference should be distinguished from professional responsibilities and fiduciary duties for which in-house counsel owes solely to the corporation as his/her client). Providing legal counsel to the business in order for legal and regulatory risks to be fully appreciated and considered in the decision-making process must be a top priority for in-house counsel. In my experience, lawyers are rarely called upon to advise on apparent illegal behavior. In large organizations, there should be various safeguards such as compliance programs, risk controls, and corporate policies. Moreover, it is fairly easy to advise on unlawful conduct with a simple “You can’t do it.”

Normally, as it relates to client counseling, the business will seek advice from in-house attorneys on new business initiatives, situations where the law is difficult to apply, and contract interpretation issues. In those cases, you and your team are responsible for explaining the legal/regulatory risk, litigation risks, its potential impact to the business, probability of realizing such risk, and potential solutions. The law department can create tremendous value for the business by identifying legal or regulatory opportunities to advance the business objectives. For example, developing a new barrier to enter the company’s market through intellectual property rights or advocating for a statutory or regulatory change. Often, thinly staffed in-house legal teams find themselves too consumed by day-to-day work and reacting to internal clients’ requests to identify opportunities for proactive legal advice. In order for your team to be proactive, you will need to make it a priority for your team and provide adequate support such as time and coaching. Keep in mind that your company is currently developing the “facts” that other lawyers will scrutinize when assessing legal risks months or years from now. One of your key responsibilities includes working with your team to identify these areas of potential future legal risk, and ensure that the controllable facts developed today will be advantageous to your clients’ position in the future.

Client satisfaction

Regardless of whether you practice in-house or at a law firm, lawyers are service providers and client satisfaction is important. In large law firms, client satisfaction is essential to the firm’s long-term viability and this is ingrained into the culture of large law firms. Most large firms seek to deliver extraordinary client service based on high quality work, successful results, responsiveness, on-time delivery, catering to client demands, and a host of other factors. The culture developed by most firms as a result of this overarching focus on client satisfaction has created some challenges for firms, including a high turnover rate of attorneys. It is important for the business to view the in-house law department as valuable to the business. The client satisfaction skills you developed at the firm have relevance and value in the in-house environment as well. However, you face a unique challenge since client satisfaction may be defined differently in-house and influenced significantly by the larger organization’s culture. To develop the appropriate approach to client satisfaction, your analysis should take into account the reasonable expectations of members of your team, including work/life balance; the organization’s culture; the law department sub-culture; your internal business client’s expectations; and your own expectations. It is important to develop a culture where your lawyers focus on providing great customer service while maintaining their ethical duty to the company as the client. In-house counsel will encounter situations where he or she will need to challenge or, in rare instances, object to internal business client initiatives to protect the interests of the company. Placing client satisfaction as the top priority could be a mistake in an in-house environment.

Adopting a law firm client satisfaction approach of “lawyers working around the clock” may not be necessary to achieve high client satisfaction at your company. Although in-house legal practice is far from a 9-to-5 career, a key difference between in-house and law firm practice is having a predictable work schedule, which allows attorneys to plan for time with family, vacation, exercise, and other non-work activities. This is predicated on the internal business clients involving in-house lawyers early in projects because they trust that the lawyers will add value. By establishing a good relationship with clients, you will enjoy far greater influence when establishing reasonable client expectations, receiving assignments well ahead of the due dates, and engaging your team early on projects, all of which in turn provides team members greater predictability with their schedules.

Within your first 90 days, seek to understand your business clients’ expectations around workflow and turnaround time. Use such information to reconcile any differences between your client’s expectations and your team’s actual practice. If you manage this process properly, members of your team can continue to maintain a reasonable work/life balance, which is a competitive advantage when recruiting talented lawyers away from law firms.

Culture

I describe organization culture as the norms and values in an organization that influence behavior, communication, and decision-making. The culture of the organization can be observed in various ways, including the way employees communicate with peers, subordinates, and superiors. Another way to observe culture is by examining the decision-making process, including who has authority and how such authority is exercised. Through both examples, one can quickly determine whether the organization relies on consensus-building, or command and control to make decisions. Additionally, one may be able to determine whether employees are comfortable challenging ideas and how and where such challenges occur.

Understanding the organization’s culture will be key to your success. You may elect not to conform to all aspects of the culture but you should fully understand the potential implications of your decision. If the culture is to leave office doors open to invite collaboration among coworkers, it may not be well received if you work with your door closed and require appointments for meetings. Or, it may not be well received if you are expected to answer your own phone, but you elect to have your assistant take your calls like you may have done at the firm in order to minimize non-urgent interruptions. Doing such things may cause you to develop an aloof reputation in the organization. It may impact various perceptions of you, make you less effective as a leader, and diminish your influence.

Although you may not need to conform to all cultural norms in your organization, those you elect to change should be consistent with the organization’s core principles. If nearly all of Company A’s employees sit in private workspaces (such as offices or cubicles) and Company A highly values collaboration among employees, you will have more flexibility to change your team’s workspace from private to open collaboration space. Although you may fail to conform to a norm, doing so in a manner to advance the strategic priorities of your team could distinguish you as a leader in the organization.

Establishing your management framework

At large law firms, successful attorneys develop strong leadership skills often through leading a team of lawyers and paralegals on large sophisticated matters. The leading lawyer must influence and motivate others on the team to give the project high priority; work effectively as a team; complete deliverables on time; identify and solve unexpected legal, regulatory, or tax issues; and often work long hours. The skills required of a law firm attorney to influence and motivate others, foster teamwork and collaboration, effectively communicate with the team and client, and develop less experienced legal professionals are valuable leadership skills developed through the law firm experience. If you leverage these skills appropriately, they will lead you to a successful career as an in-house manager.

In addition to important leadership skills, you assume significant supervisor responsibilities as an in-house manager. These supervisory responsibilities distinguish leaders from managers in an organization. A good manager must be an outstanding leader and at least a competent supervisor, while a great manager will be excellent at both. Most professionals (including non-lawyers) find it difficult to administer supervisory responsibilities, which include (1) administrative reporting obligations; (2) delivering unpleasant messages to members of the team; (3) making tough decisions about the careers of other people; and (4) being held accountable and receiving credit for work executed by members of the team.

Since you determine each team member’s performance rating, compensation, promotion, assignments, and development opportunities, your team members will be acutely aware of any formal and informal communications and suggestive behavior regarding your expectations, your values, and how you make decisions.

Prior to your first day in-house, spend some time developing your leadership philosophy, which requires self-reflection. In your leadership philosophy, clearly articulate the core values that heavily influence your decisions, behaviors, and thinking as a leader. Complete each section of the Personal Leadership Philosophy (PLP, see sidebar) by preparing approximately five bullets or a descriptive paragraph under each area. You may find it helpful to consider those leaders you admire and allow their leadership qualities to influence your philosophy. It is important that your PLP reflects your own beliefs and principles. Once you finalize your PLP, discuss it with your team. You will gain the trust of your team by being open about your experiences.

Your PLP should be a living document and will likely evolve over time to reflect your future experiences. Review it annually and make any applicable modifications.

Managing the new manager

30/60/90 day plan

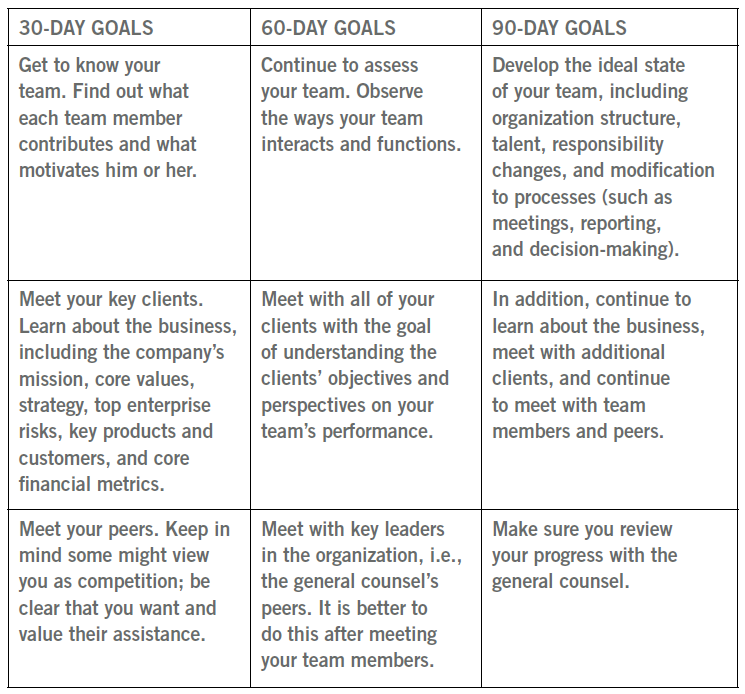

There are unique challenges to hiring a seasoned attorney from a law firm to an in-house management position. Your manager, which is assumed to be the general counsel, can play an instrumental role in your success. It is important for the general counsel to design a plan to provide you the best opportunity to successfully transition to the company. A plan that establishes target completion dates, such as 30 days, 60 days, and 90 days, provides two benefits. First, it allows the general counsel to prioritize the important initial steps in your transition and establish target dates. Second, the plan may serve as a development plan and basis for one-on-one discussions. Third, and probably most important, it allows you to formally reach alignment on the expectations of the general counsel. Lastly, with such a plan in place, you are less likely to feel overwhelmed with a clear road map on how to be successful at the company with target dates for completion.

Seek to cover the following actions with your 30/60/90 day plan:

Throughout the execution of the 30/60/90 day plan, the general counsel should actively coach you. During the early transition period it will be valuable for the general counsel to offer you frequent and thoughtful guidance, but the general counsel should also encourage independent decision-making. Frequent meetings with him or her during the first 90 days will allow you to make course corrections and avoid catastrophic mistakes. You may want to share this article with your general counsel as a way to introduce a discussion on the items in this section.

Flexibility to make decisions

It is important that the general counsel empowers you to make decisions relating to your team but coaches you to avoid making serious mistakes. The general counsel should provide you with the appropriate level of authority and flexibility to make decisions and support your decisions, provided such decisions do not place the organization at significant risk. It’s important that the general counsel avoids inadvertently undermining your decisions or it will cause others to unfairly question your authority and cause you to be less effective at a time in which it is important for you to gain the confidence and trust of your team and clients. Understand when to involve the general counsel. Each general counsel is different, so you may be surprised by his or her response. The general counsel’s interest may be far-ranging such as key deal terms, to settlement of a dispute, to the hiring and salary negotiations of a new employee.

Communication

Effective communication between you and the general counsel is especially important during your transition period. He or she should share feedback from others in the organization, both positive and negative, about your performance and use it as valuable coaching opportunities. The general counsel should also assess the execution of your transition plan and provide regular coaching at the appropriate points.

Also, figure out quickly how your general counsel and business executives desire to communicate with you. Is it verbal, voicemail, or email? You will generally find that corporate executives do not communicate the way you did with other attorneys, regulators, or courts. I’ve yet to find any business executive who desires to read a legal memorandum. They often prefer to receive communications in succinct bullet points. Try to avoid using legal jargon in communications and include the potential business impact (i.e., a statement on profit and loss) including probabilities of the outcome. Lastly, make your recommendation up front and provide the relevant detail later as an optional read.

Executive coach

After you have been in the position for a year, if you demonstrate potential to be successful in the organization, the general counsel should consider hiring an executive coach for you. A good executive coach will accelerate your growth and development and, in turn, make the general counsel’s team stronger. If the general counsel does not offer you an executive coach, strongly consider requesting one as part of your development plan following your first anniversary with the company.

As an example you can structure a Personal Leadership Philosophy (PLP) focusing on five areas:

- What I believe (should answer “I believe leadership is …”);

- What I expect (should clearly articulate what you expect from each member of your team such as collaboration or keeping you informed);

- What I will do (should clearly set out your commitments, such as treating team members fairly or providing honest feedback);

- What I will not tolerate (make it clear what behavior you will not tolerate. It will be important to hold each team member accountable or you will lose credibility); and

- What makes me happy (what genuinely makes you happy; it is fine not to limit this section to work).

Conclusion

An attorney gains many valuable skills while practicing at a large law firm. Technical legal skills top the list, but many other soft skills critical to your success as an effective manager are gained along the way such as the ability to quickly assess talent, to develop legal professionals, and to provide a high level of service to clients. How the soft skills are leveraged to maximize value in a law firm could have an adverse effect in an in-house environment. Retooling your skills for your new in-house management position will offer you certain unique advantages over other in-house managers and lead to a very successful transition.

Further Reading

1 Linda Hill, “Becoming the Boss,” Harvard Business Review (Jan. 2007).

2 Milton C. Regan, Jr. and Lisa H. Rohrer, “Money and Meaning: The Moral Economy of Law Firm Compensation,” 10 U. St. Thomas L.J 74, 106 (Fall 2012).

3 Deena Shanker, “Why Are Lawyers Such Terrible Managers?”, Fortune (Jan. 11, 2013).

4 Randall Beck and James Harter, Why Good Managers Are So Rare, Harvard Business Review (Mar. 13, 2014).

5 Id.

6 Milton C. Regan, Jr. and Lisa H. Rohrer, “Money and Meaning: The Moral Economy of Law Firm Compensation,” 10 U. St. Thomas L.J 74, 76-77 (Fall 2012).

7 See Shanker, supra note 3.

8 ee Regan, Jr. and Rohrer, supra note 7, at 76.

9 See Regan, Jr. and Rohrer, supra note 7, at 81.

10 Such tools include, but not limited to, the ability to hire, terminate, promote, and reward individuals, create development plans for team members, and reorganize the team to drive greater effectiveness.

11 Anne Fisher, “Are Annual Performance Reviews Necessary?”, Fortune (June 27, 2012).