One of the most common, yet underappreciated clauses across a wide range of agreements is the dispute resolution clause. Dispute resolution clauses are often multi-tiered, to explore whether lower-cost, abbreviated methods will work before the parties need to engage in more expensive and procedurally elaborate methods.

Typically, the first step in a multi-tiered dispute resolution clause is negotiation, followed by mediation, and then arbitration or litigation. In industries ranging from construction and real estate to technology and financial services, legal counsel have pushed for the wholesale inclusion of binding dispute resolution clauses in sales and service contracts, and such clauses have often been upheld by the highest US courts.

When properly tailored to the subject matter, dispute resolution clauses can save time and money for both parties because they focus the introduction of evidence on the most relevant facts and involve a neutral decision-maker or facilitator who already has general background knowledge of the subject matter of the dispute, such as building codes that may be relevant in a construction dispute.

By contrast, courts necessarily handle a far wider range of disputes and, thus, judges are often not as deeply familiar with particular industries. This is one reason why the inclusion of dispute resolution clauses in commercial contracts is on the rise.

To support this growing demand for non-judicial dispute resolution, the number of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) providers is increasing in both the online and offline worlds, with internet-based organizations creating a new category: online dispute resolution (ODR).

Case closed?

Has the increasing inclusion of dispute resolution clauses resulted in faster and more efficient resolutions? Less so than expected, because these clauses are often not drafted with sufficient care. They are nicknamed “midnight clauses,” as they are often the last section included in a contract, perhaps as an afterthought or mindlessly cut and pasted from a prior template. As a result, dispute resolution clauses themselves can be the source of further disagreement between the parties, who have different interpretations about its meaning.

Oftentimes one party will argue that the negotiation and/or mediation portion of their multi-tiered dispute resolution clause is not enforceable due to uncertainty. Thus, they argue for an immediate start to arbitration.

This results in the other party seeking court assistance to enforce the mediation portion of the dispute resolution agreement. Unfortunately, courts provide inconsistent answers as to the enforceability of the mediation portion of such agreements. Thus, the number of lawsuits pertaining to dispute resolution clauses continue to rise.

An example of such a legal dispute is Emirates (2014), where a condition precedent to arbitration was a “requirement to engage in time limited negotiations.” The arbitrators held that such a requirement was not enforceable in arbitration.

The party seeking to enforce the negotiation requirement then brought the matter before the England and Wales High Court (Commercial Court), where Justice Teare upheld the negotiation clause as part of a wider multi-tiered dispute resolution clause because the clause specified a finite amount of time for the negotiations and good faith negotiations could forestall the need for expensive arbitration.

During her PhD research, Maryam Salehijam, one of the authors of this article, examined 172 mediation clauses and found that such agreements were often only deemed enforceable in a cross-border scenario if they contained extremely detailed requirements for the dispute resolution process. The requisite details included, but were not limited to:

- The scope of the mediation clause (disputes covered);

- Description of the procedure (e.g., how to initiate the mediation, minimum attendance requirement, how to terminate the procedure);

- Procedure to select the mediator(s) and his/her payment;

- Timeframe for the mediation or a timetable for compliance; and

- Clarifications regarding obligation to refrain initiating arbitration.

Key elements of dispute resolution clauses

Review your own dispute resolution clauses and consider whether they contain sufficient detail. When crafting a dispute resolution clause, some key decisions to address include:

- The scope of the clause: Which types of disputes does it cover?

- A detailed explanation of the one or more dispute resolution mechanisms to be deployed, the individuals to be involved in the dispute resolution process, the method for the selection of the neutral, matters pertaining to payment of both the neutral and other costs, the location of the neutral and in-person sessions, and prescribed timelines for negotiating, filing, and adjudicating matters.

- Governing law of the dispute resolution clause.

- Who has jurisdiction to remedy disputes involving the dispute resolution clause itself.

- A provision regarding the consequences of not complying with the dispute resolution clause.

While explaining the above requirements sounds simple in theory, extensive research and attention to detail are required to specify the processes appropriate for your matter. Depending on the dispute resolution mechanism selected, the level of detail needed varies.

Moreover, each jurisdiction may have its own requirements about specificity of your dispute resolution clause. For more thorough planning, consider augmenting your library with a book on the nuances of crafting dispute resolution clauses, such as the forthcoming Mediation and Commercial Contract Law: Towards a Comprehensive Legal Framework.

Why conduct all this research upfront? Because a failure to include sufficient detail in the dispute resolution clause of your agreement may force a court to fill in the gaps using default rules or find your dispute resolution provisions enforceable due to uncertainty.

Despite the employment of alternative dispute resolution clauses for decades, many contracts still contain badly drafted dispute resolution agreements. This is evidenced by the ongoing tide of secondary legal disputes regarding dispute resolution clauses.

For example, there are a growing number of disputes relating to the parties’ mediation agreement. According to a study by Cole,

“In the seven-year period from 1999 to 2005, the number of reported opinions on Westlaw that addressed mediation issues increased from 172 in 1999 to 521 in 2005, a 303% increase.”

Particular points of contention related to mediation clauses are: when are these agreements binding on the parties; should these agreements be enforced; and how should breaches of these agreements be remedied?

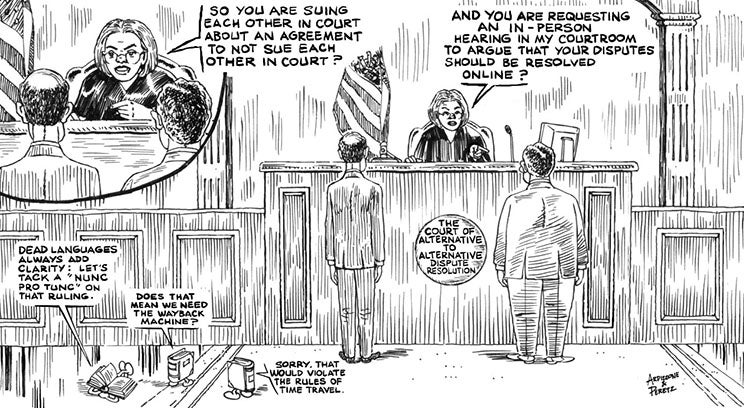

In essence, clauses intended to facilitate the resolution of a dispute are creating more disputes, as each party uses its own procedural interpretation to jockey for an advantageous position, akin to forum shopping in the world of litigation. It is paradoxical for parties to have a secondary legal dispute regarding their dispute resolution clauses, as the intention of the parties in crafting such clauses is to avoid disputes. This phenomenon is labeled the “disputing irony” by the academic legal community.

Your game plan

To take advantage of properly tailored dispute resolution clauses, it’s time to examine your contracts. Which ones contain a dedicated dispute resolution clause? Is it tailored to your industry and the types of disputes you have most often? Does the agreement specify limits on which items should be subject to private arbitration?

Several companies have had hundreds of simultaneous arbitration cases filed by partners or customers at the same time. In one case, the company was asked to separately arbitrate over 15,000 allegations that the company failed to secure customers’ personal data and provide adequate notice to them after a data breach.

Had the company carved data breaches out of its arbitration clause, it could have dealt with this matter through a collective action, rather than engage in thousands of individual arbitral proceedings, each of which require payment to the arbitrator and separate counsel for each matter.

In light of pandemic-inspired social distancing and the distribution of work across more locations, it’s time to learn more about online dispute resolution as well. You can use your popular contracts as a testbed to explore new dispute resolution approaches: Try an online dispute resolution clause in some agreements and compare it to how disputes are handled with a more traditional dispute resolution clause.

Just as internet companies run A-B comparison tests online by presenting variations of their website across their customer base and gauging responses, you can do the same by varying language in your common agreements and observe the results.

You can also consider applying online dispute resolution technology and processes for use by your own team. One company, eConciliador, which provides technology to facilitate online dispute resolution, claims that many of its disputes are settled in less than five minutes. And other technology companies like Resolve Disputes Online or CREK ODR are providing technology tools that can be utilized by third party neutrals to bring existing processes and parties online.

As business relationships continue over time, they are often augmented with addenda, amendments, and additional statements of work. It’s important that you look across the multiple documents that define your longstanding relationships to ensure that their dispute resolution clauses are consistent.

This was a hard-won lesson for businesspeople in the Tenth Circuit not long ago, albeit with then Appellate Court Judge Gorsuch dissenting. Over a period of time, the plaintiff and defendant were party to six different agreements with each other, each with different dispute resolution rules related to key topics such as the arbitrator selection process.

Due to the conflicting provisions in the parties’ multiple dispute resolution clauses, the court determined that the arbitration clause was unenforceable, and the matter should be litigated in court.

Cross the table before the bar

As your company continues to grow, you have likely inherited all sorts of agreements and attendant dispute resolution clauses, some of which could stretch across multiple documents (e.g., statements of work). Grab a few agreements each week and run a tabletop exercise about the steps and cost to manage disputes related to these.

Do you need to hire Delaware counsel? Could you end up being sued in state court in Louisiana? Will you need to pay US$600 per hour for an arbitrator to resolve certain matters?

What you will find from this tabletop exercise is that you likely have many fora in which you may need to fight, and some can be quite costly in terms of both time and money. This potential cost/risk may provide additional persuasive evidence to your management colleagues to finally get a system and service to review all your legacy agreements so you can find and reduce these risks.