Unless you are nearing your centennial birthday (if so, congratulations!), you are about to experience the largest wave of bankruptcies in your professional career. Record levels of unemployment and restructurings of iconic names like JCPenney are just a precursor to the dramatic economic changes that we will soon be facing. At present, much of the impending turmoil is still hidden from public view due to a boisterous stock market and the incredible amounts of government aid and landlord forbearances.

The rise of COVID-19, in addition to immediate deaths and lingering health challenges for many, is also likely to result in substantial consumer behavior change in certain sectors. Many people will rush back to the movie theaters and the mall as soon as possible; however, a subset of the population will likely be forevermore cautious.

If you have ever met anyone who lived through the Great Depression or other similar challenging economic times, you may have seen how they are far more focused on saving and reusing seemingly items that others deem disposable. We expect to see a subset of those experiencing COVID-19 to have a similarly lasting behavior change, which could impact the extent to which they partake of activities such as large gatherings and cramped flights.

The impact of this behavior change is that certain industries will discover that they have built out more capacity than they need for the foreseeable future, often using leverage to do so. Even companies that may bounce back completely after the pandemic have loaded up on extra debt, including drawing down credit facilities, to weather these times. As a result of these trends, many companies are going to need to restructure their balance sheet and will likely use the bankruptcy process to do so.

The United States has one of the most sophisticated bankruptcy processes and sets of rules in the world. It excels at finding the best possible use for assets in a manner that enables repayments to creditors. A trade-off to its efficacy is that it is quite complicated and full of landmines for the inexperienced, even if they have a law degree.

It can take years to learn the tricks and traps of being effective in bankruptcy proceedings, either as a creditor or debtor, and you likely do not have that much time before your business could be impacted by an actual bankruptcy proceeding. What you can do right now is to develop a framework for understanding bankruptcy at a high level so you can explain it to your business colleagues.

Dreaming of pies

A helpful way to conceptualize the bankruptcy process is to envision the assets of the debtor, called the Bankruptcy Estate, as a gigantic pie. The larger the pie, the more people that can be fed. The Bankruptcy Code provides extensive mechanisms related to assessing the size of the pie and who is entitled to a piece.

Prior to filing bankruptcy, anyone owed money or property may take the obligor support to seek recompense. Those who go to court sooner are likely to get recompense sooner and perhaps more fully. Once a bankruptcy petition has been filed, the opportunity for this unilateral action to get your piece of pie is typically forbidden.

At its heart, the Bankruptcy Code is concerned with two meta-activities: growing the pie and dividing the pie. We will discuss each in turn.

Collecting those I-O-Mes

When an entity (including an individual) files for bankruptcy, the petition is supposed to include the debtor’s understanding of all of its assets: essentially the start of the pie. For many debtors, however, there are other assets that could be included in the pie that are not presently in the debtor’s possession. For example, the debtor may have had to close its business due to a pandemic or other unforeseen event.

If the debtor has Business Interruption insurance that covers such an event, then there may be more money that can be put into the debtor’s estate by filing an insurance claim. The debtor may also have assets in the possession of others that it needs to have returned. And perhaps willfully, or accidentally, the debtor transferred away some of its assets while it was already financially insolvent yet had not filed its bankruptcy petition.

The Bankruptcy Code contains many processes to marshal these assets so they can be divided by the court. Avoidable Preference actions and Fraudulent Transfer actions can be used to address improper prepetition transfers of the debtor’s assets to third parties. Reclamation actions can be filed against those who may be in possession of assets of the debtor that need to be returned. The debtor may be given permission by the bankruptcy court to engage in litigation to pursue claims that could lead to additional value for the debtor’s estate, such as suing an insurer over an unpaid claim.

Actions to grow the pie are typically overseen by the debtor itself or perhaps a trustee appointed by the bankruptcy court. If you are a creditor in the case, you’re less likely to participate in the activities of drawing the pie unless your claim is relatively large.

Sharpen those knives

The area where creditors are most involved in a bankruptcy is seeking the largest slice of pie possible and jockeying to get a spot earlier in the queue for pie division in case there is insufficient pie for everyone to get the slice that they deserve.

The Bankruptcy Code and surrounding case law contains many mechanisms and rules to stratify creditors into different classes, with each class possessing different rights regarding when it can seek its slice of pie and how to calculate how much is owed. Due to the ongoing evolution of types of claims, the Bankruptcy Code has been unable to address in particularity each and every issue that might arise in a claim.

Accordingly, bankruptcy courts have been tasked with interpreting the code and applying it to new situations. This means that much of the guidance about how to position your claim in bankruptcy is found in the case law, rather than in the statutes itself. On paper, the bankruptcy law should be uniformly applied across the country. The United States Constitution (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 4) authorizes Congress to enact “uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States."

As with so many other areas of law, reality is more complicated. In keeping with Justice Brandeis’ idea about the United States as the embodiment of many parallel “laboratories of democracy,” you can think of various judicial districts and circuits as representing “laboratories of bankruptcy.” Essentially, you need to understand the jurisprudence in the relevant circuit when preparing your claim as a creditor in bankruptcy.

Due to the specialized nature of bankruptcy law and jurisprudence, if you want to maximize the prospect of a good recovery for your claim as a creditor, obtaining expert advice can be invaluable. Bankruptcy experts can figure out how your unique facts can be positioned as a secured claim, priority claim, administrative claim, or perhaps applicable to a non-estate asset.

Is my pie slice valuable enough to pursue?

Most experienced in-house attorneys make a cost-benefit calculation about the amount they want to spend, both in terms of time and money, when pursuing a particular matter. The key aspect of a cost-benefit analysis is assessing the value of the likely benefit.

In bankruptcy, you may need to make investments in pursuing your claim before you can find out what your claim might ultimately be worth. The bar date on filing claims in a bankruptcy may arrive well before you can discover whether the debtor or trustee have been able to expand the pie, which enables a bigger slice for everyone. And you will not know until the claims bar date how many other creditors have queued up for a pie slice, which could impact how much pie is left for you.

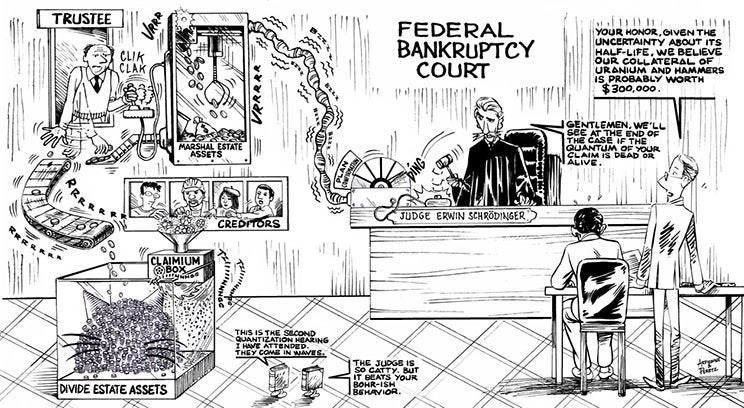

Much like physicist Schrödinger’s cat was in an unknown state of dead or alive until its box was opened, your bankruptcy claim is in a similar state of fluctuating value until the end of your case, when you discover the overall size of the pie and who else is seeking a slice.

The uncertainty of the ultimate value of your claim can complicate decision-making about how much to invest to pursue it. While you already know that all lawyers are expensive, bankruptcy attorneys lead the pack these days in terms of billable hour rates. At least one large law firm has been reported to charge up to US$1,000 per hour for its senior associates in its bankruptcy practice. Despite these hefty price tags, there is still a shortage of bankruptcy experts around.