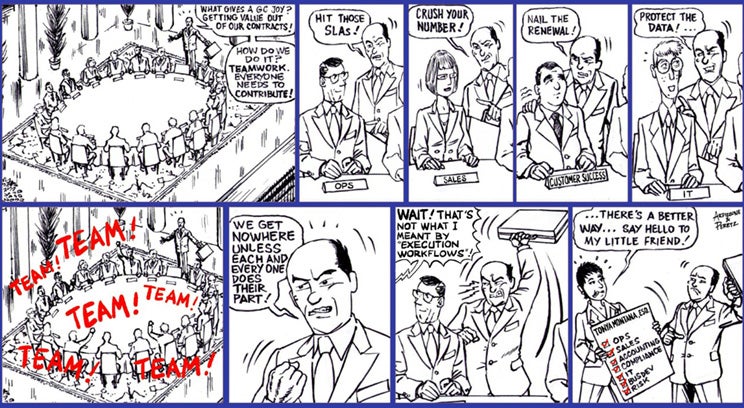

In-house counsel are often the primary contact for negotiating certain types of contracts. However, in this role, you are not in charge of executing all the terms and commitments in each agreement. Agreements typically require many teams and departments to engage in or abstain from certain activities.

For example, your IT team may need to affirmatively send a copy of your penetration testing results to your partners on an annual basis. And your colleagues in human resources need to abstain from recruiting employees from a consulting firm that included a non-solicitation provision in its agreement with your company.

When you are negotiating agreements with a counterparty, the best in-house counsel spot the issues that affect each department in their company and consult the stakeholders ex ante about whether they can truly meet the requirements in the agreement. Can your accounting team accept 63-day payment terms? Is your business development ready to give an exclusivity for your entire region? And, if so, for what products and for how long?

Eventually, the stakeholders on both sides coalesce around acceptable terms. Then what happens next? Often, nothing. Every stakeholder involved in an agreement is busy with two dozen other projects as well. Once an acceptable negotiating position has been reached, sales is focused on the next deal, accounting is concentrating on the upcoming audit, and human resources is gearing up for on-campus recruiting season.

What about all those commitments made by each team during the contract negotiations? The answer is (too) often: “Don’t worry about it. We’ll take care of it when the need arises.”

Then people leave the company or change positions or take a vacation. And their knowledge of what needs be done for each contract is lost or forgotten. Essentially, commitments of your entire organization are lost because they are tethered to individuals with their own priorities and trajectory.

Aud(it) man out

Some companies attempt to reconnect contracts to work commitments on a quarterly or annual basis by conducting account reviews. The company-appointed owner for a particular contract, if he or she can be found, is asked about the status of the relationship amidst her many other commitments. Even for a responsible contract “owner,” this audit triggers the workplace equivalent of a wild goose across multiple teams, personnel, and deliverables.

Except for the most persistent and detail-oriented contract owners, the path of least resistance is often a rubber stamp renewal of the agreement, perhaps based on the premise that the contract was put into effect by a predecessor for an unknown, but undoubtedly important, purpose.

In this time of economic belt-tightening, a rubber stamped perfunctory audit is less likely to be acceptable. One of the fastest ways for companies to save money is for companies to scrutinize their existing agreements to verify both compliance and value extraction. And, while an occasional retrospective audit of existing agreements is a good first, it is still too reactive as a strategy and leads to suboptimal results.

A few years ago, my son asked why he needs to wear a seatbelt in the car. I explained that it would keep him safe in the event of an abrupt stop or collision. He thought for a while and retorted (like one might expect from someone living with a lawyer): “Well, then why don’t I just put on the seatbelt before we crash?!”

Conducting occasional retrospective contract audits is like trying to put on your seatbelt while you are already crashing. It’s simply too late. What comes out of an audit is typically vindictiveness about who messed up, rather than lessons learned for the next time. Much like sitting around the hospital after the accident discussing why the passenger wasn’t wearing a seatbelt.

Forewarned is four armed

The best organizations take a more proactive approach to their contractual rights and obligations. They wear their seatbelts and make sure everyone else does as well. As an in-house counsel, you are well-positioned to influence this type of perspective and behavior in your own organization.

Of course, as an attorney, it’s unlikely that you directly manage sales, marketing, ops, finance, accounting, IT, or any of the other myriad teams that might have responsibilities tied to an agreement. You can yell at your colleagues after they miss commitments, but a tongue-lashing is unlikely to keep people on track in the future. Instead, you need to use your superpower: the ability to see the future!

In fact, anyone who can read a contract can see the future. There are amazing (albeit sometimes conditional) future events that can be foretold. With a mere glance at a partnership agreement, I can foretell who is most likely to bear the cost of a data breach notification. And I can guess with amazing accuracy how much advance notice is required by the scheduled downtime of a key business system.

You’ve only got two arms. How do you take this knowledge about future deliverables and expectations and turn it into the action of many arms? By turning your understanding of contracts into high-level action plans. When you read an agreement, start preparing action lists of tasks to be completed or overseen by your colleagues. Upon execution of a new agreement, and certainly, after auditing existing agreements, you should develop a list of responsibilities across your organization related to the agreement.

Leverage authority

Your role in the organization is to leverage what you have at your disposal: a copy of the contract and a general sense that some other stakeholder in the company has work to do, which could include timely receiving and examining a counterparty’s work product. What you don’t likely have is the authority to tell your colleagues what to do. Moreover, it’s unlikely that you have the skills to understand all the steps necessary to execute the contractual obligations you spotted.

Rather than having official management power, what you have is the contract itself. The contract represents a binding obligation of your organization. You need to leverage the authority and legitimacy of the contract to motivate colleagues to own and complete their share of the work to implement the agreement.

The best way to leverage the authority of a contract is to point to the document itself. The document focuses the discussion with your colleagues on the actual deliverable, rather than creating the appearance of a personal power grab. Better yet, don’t just email a copy of the 57-page agreement to your colleagues: break it down for them by section. Point your colleagues to the specific language in the contract where their team has an obligation.

There are several tools that enable you to do this. Contract Wrangler, for example, allows users to highlight specific contract clauses and assign those to others in the organization accompanied by due dates and alerts. Adobe Acrobat allows the placement of sticky notes on documents that can be clicked on to provide more detail. And Google Docs allows comments in the margins that can be assigned to particular people.

Encouraging breakdowns

The process to implement key sections of an agreement is likely more complicated and nuanced than you might expect. For instance, what appears to you to be a simple accounting obligation might require scores of journal entries into multiple systems of record. If you want accountability into your colleagues’ progress on their contractual assignments, you need to provide a system or method that lets your colleagues break the tasks down further into their subcomponents.

Enabling each responsible department to create and communicate subtasks within their overall deliverables encourages colleagues to be methodical in their process. And it provides you a more accurate view of the project status. Imagine that a contract calls for your team to construct a small building. It would be far more helpful for you to know when each floor and subsystem has been implemented than it would be to hear only “complete” or “not-complete” as the status report.

The omniscient narrator

Ideally, everyone responsible for the success of an agreement has the perspective of an omniscient narrator: Even if they do not control the action, they can see all the characters and all the steps required for each deliverable and understand the status of each one. This omniscient viewpoint should be accompanied by an alert system that lets all relevant people know before a key deadline arrives.

An alert system also addresses the reality that employees may take vacations, switch jobs, or get kidnapped by space aliens. An alert of an upcoming contract deliverable reminds everyone on the team to check on the overall project status — and note when someone responsible for a deliverable is out of the picture.

It’s too late to pitch-in on a missing team member’s deliverables when they are due tomorrow. If deadlines and alerts are set for intermediate deliverables, everyone on the team can discover when they need to replace an absent team member before it’s too late.

Top hat, not baseball bat

Carrying out agreements involving many team members and departments is the corporate equivalent of a three-ring circus. Fortunately, you don’t need to get on the trapeze or shot out of a cannon yourself. Instead, be the ringmaster who directs the spotlight by helping deploy systems that educate colleagues about ongoing rights and obligations.