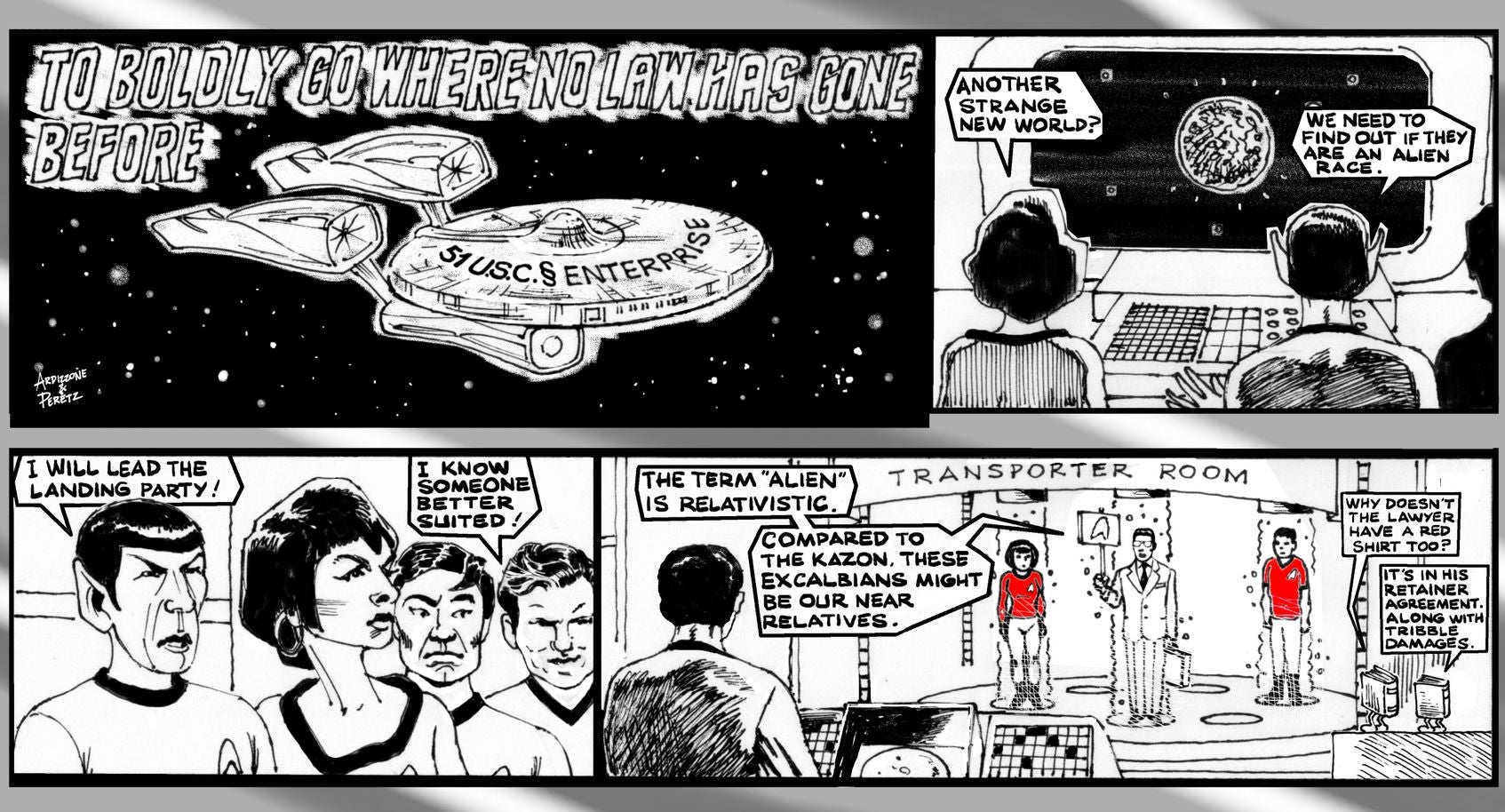

As a lawyer, whenever we encounter a new potential legal problem, we are rarely provided answers on the spot. Instead, our most common refrain is, “Let me go look that up and study it.” We answer this way because law is inherently retrospective. We are studying the past to give guidance to our clients for the future.

But what we do when there is not a sufficiently similar “past” to examine?

Recent technologies and new business models are often unaddressed by laws, regulations, and prior cases. In common law jurisdictions, we are particularly challenged because it is this case law that fills the gaps when statutes and regulations are not sufficiently on point.

In civil law jurisdictions, the court may at least have a guiding principle espoused in law that can be applied to a de novo scenario by the court. By contrast, common law courts have less flexibility in their decision-making due to stare decisis.

It’s true some fields are governed by umbrella laws that provide more general principles to follow, such as laws against unfair, deceptive, and abusive Acts and practices (UDAAP). These umbrella laws were created because Congress and regulators could not predict every possible future violation of the law.

Thus, regulators, and possibly private litigants, may develop new causes of action based on broad concepts embodied in these laws. In practice, however, these umbrella laws provide scant prospective guidance because most market participants and litigants wait for regulators to identify which types of fact patterns fall under these umbrella laws.

Given the retrospective nature of law, how should we counsel our clients as in-house attorneys when they are contemplating a new business model or the application of new technologies that are distinct from those covered by existing laws?

In common law jurisdictions, we are particularly challenged because it is this case law that fills the gaps when statutes and regulations are not sufficiently on point.

Rules from the road

Almost a decade ago, I was asked to help a new ridesharing company find a path to legally provide ridesharing services while avoiding becoming saddled by regulations that were inappropriate for their business model. Providing them legal guidance in a truly emerging field taught me many lessons.

1. Set expectations about conflict

In any market where there are incumbent players, someone will be unhappy with a new entrant and even the most airtight legal positioning will not ward off potential litigation and regulatory inquiries.

For example, in ridesharing, the taxi and limousine companies, many of whom held oligopolistic licenses for certain territories, were sure to raise a fuss. Accordingly, my first step in advising my clients was to advise them to set aside a budget for litigation and potential regulatory investigations. Even on the sturdiest legal footing, my clients would be challenged by those seeking to create a public spectacle or perhaps bankrupt my client.

Make sure your client is ready to invest in a fight!

2. Cover stories matter

Even in a strict liability setting, one’s state of mind and intentions matter to human factfinders. In a regulatory inquiry or tribunal, one will be treated more sympathetically when one has demonstrated a concerted effort to comply with the law before taking any actions.

For the ridesharing company, I advised my client that we should develop a detailed examination of all potentially applicable legal classifications, regardless of how ill-fitting to their business, and either how my client might be able to comply with each or why the classification was inapplicable.

This study enabled my client to say that its intentions were law-abiding because it did not take a single operating step until it uncovered all the applicable laws and determined how it would comply.

3. Find the best basket

A key goal for the in-house attorney is to examine all possible categorizations that could apply to your business and influence the business model or application of technology itself to fit into the most preferred basket.

You should not just be reactive and feel obliged to find a legal home for any technology or business model thrust at you.

You should not just be reactive and feel obliged to find a legal home for any technology or business model thrust at you. You need to learn the levers in the business model and technology that can be twisted without breaking the economics and market impact that your company is seeking.

Think about how manipulating these levers can potentially shoehorn your business into your most favored categorization or escape from the ambit of the most oppressive regulatory schemes.

In the ridesharing world, for example, we looked at a variety of business categorizations: were we a new kind of common carrier? Could we form a private club of company customers, and would it exempt us from certain rules? If we limited ridesharing to friends, how might one define that term “friend” and would it encompass social media friends or friends-of-friends?

A common theme across many regulatory categorizations that were ill-fitting for the business was that they were all on receiving fares. To escape those categorizations, I suggested changing the business model to eliminate charges for transportation and find other ways to recoup costs.

The result was we launched a free ridesharing service, where riders were given an opportunity at the end of the ride to provide a gratuity to the driver. In order to help everyone assess what might be an appropriate tip, we shared information about how much others tipped for a ride of a similar length.

4. Train your people’s people

As an attorney, it’s likely you will deal with only the most senior executives in the company or your division. Remember that scores of other team members (perhaps thousands) in your organization are describing your business and business model to the public daily.

In the case of ridesharing, each one of our drivers could be asked by a reporter, regulator, or a spy for a competitor about our business terms and business model. If a single driver were to erroneously report that she received a “fare” instead of an “optional tip,” this would be duly recorded and used as a weapon to undermine our carefully developed regulatory positioning. To address this, we created talking points for all drivers that explained the business model and requested that they pass inquiries about it to a particular senior executive in the company.

Once you develop the appropriate positioning for the company, make sure that even part-time workers can understand it and communicate it clearly and uniformly.

5. Remember the fragility of the commerce clause

My ridesharing client heard about federal laws and license frameworks that sounded on paper, like a regulatory shortcut for the business that could preempt a complicated patchwork of state laws. In reality, the federal government had not occupied the local transportation field, so it was unlikely that a magic federal silver bullet could solve all our regulatory challenges across the country.

But how could I, the in-house attorney, counteract the enthusiasm of the allegedly expert outside counsel?

The answer: Caselaw.

Not surprisingly, we had outside counsel eager to generate fees by studying these federal options and seek vaguely structured meetings with federal officials on our behalf. My client had a very limited legal budget, and I was worried that the time waiting for the completion of such a study could lead to incorrect representations to investors about our corporate legal positioning.

But how could I, the in-house attorney, counteract the enthusiasm of the allegedly expert outside counsel? The answer: Caselaw.

My law clerk and I looked across the country for cases where a local transportation law violation was preempted by federal law. Not surprisingly, we found extensive caselaw to the contrary. Summarizing the facts and holdings of these cases proved decisive in convincing the business’ senior executives to not rely on a non-existent federal solution to inherently local issues.

6. Remember your audience when trying to change laws

As soon as we launched our service, we actively engaged legislators across the state about how current laws were not well-suited to our new business model. While the legislators were polite, they did not want to hear about new opportunities for societal efficiency that our business offered. Nor were they persuaded that the advent of new technologies necessitates the creation of new laws.

Instead, what the regulators cared about was their voting base. We needed to couch our regulatory requests in terms of jobs we could create and pollution we could reduce, because those messages would resonate with the legislators’ voting base.

Focus legislative advocacy efforts on how you can help the legislator look effective instead of droning on about your new technology.

Conclusion

The core requirement for implementing each of the lessons discussed herein is that you develop a deeper understanding of your business’ economics and building blocks. This represents a great opportunity for you to join the advance party for the next business expedition, rather than being left to pick up the pieces afterward.