While pandemic shelter-in-place restrictions should lift once vaccines become more widespread, the experience has likely triggered substantial long-term changes in many industries. The results of this cultural change will reverberate through industries like entertainment and commercial real estate for years to come, with many players in these industries needing to rejigger their capital structure to accommodate lower demand. In the United States, outside of the capital markets, one of the most common approaches to restructuring is the bankruptcy process.

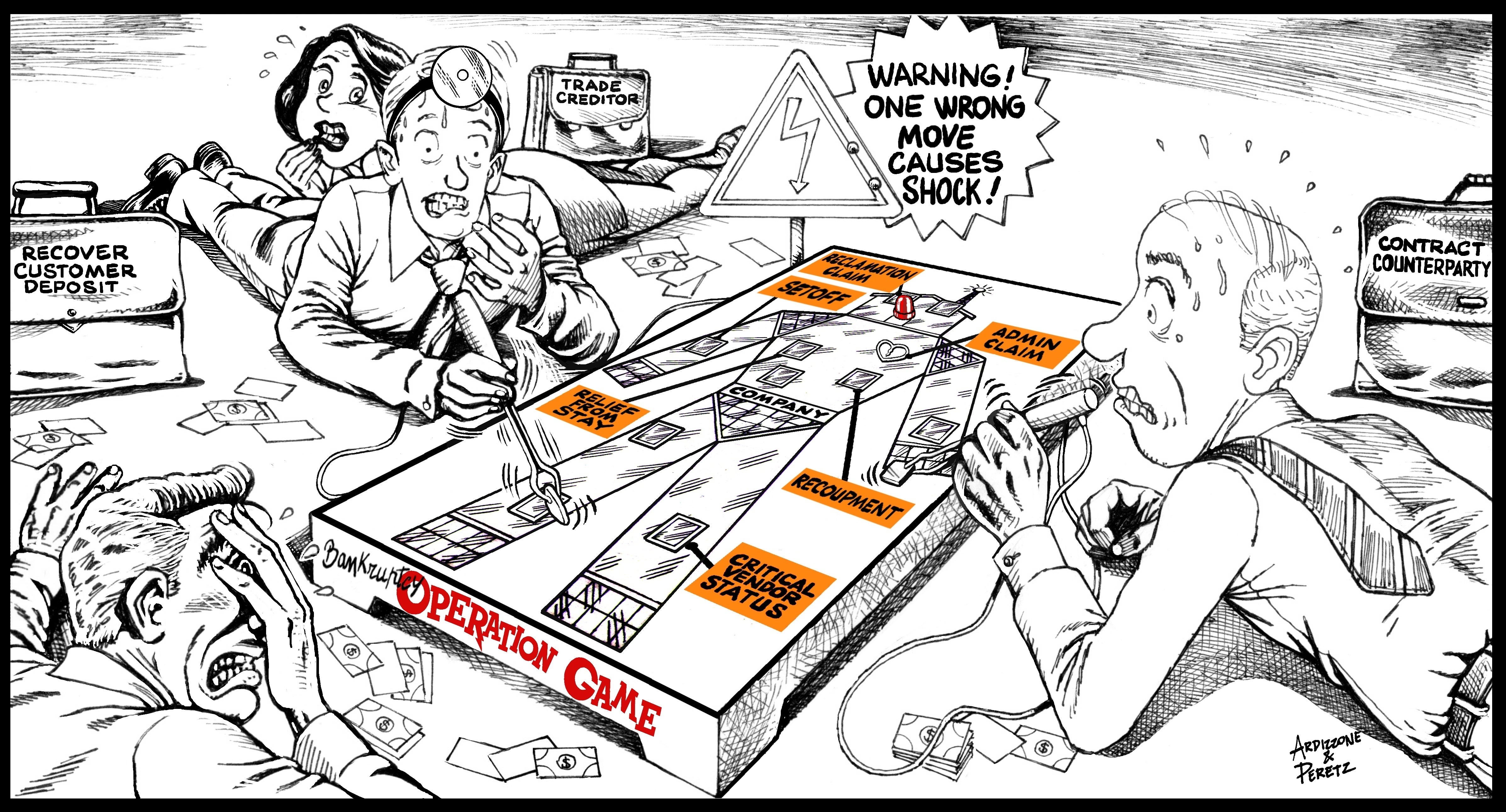

Bankruptcy is an arcane field, mixing game theory, deal making, litigation (including three levels of appeals), math, capital markets, mergers and acquisitions, ultra high-speed proceedings, novel equitable considerations, unique discovery mechanisms, and dramatically dispositive circuit splits. While it’s wise to get expert help, your in-house clients will first come running to you for guidance when they receive notice of a customer or partner’s bankruptcy.

This article provides perspectives that in-house counsel can apply to identify potential paths of actions and risky moves to avoid when discovering their company is now a creditor in a bankruptcy proceeding.

Take a broader view of your relationship with the debtor.

If you work for a larger company, it is possible that your organization is not just a creditor — you may owe the debtor money as well. For example, if you are a customer of the debtor and have not paid a prior bill, at the same time the debtor has failed to deliver on a payment you did make.

Monies that you owe to the debtor may be offset against your claims against the debtor; however, this might not happen automatically. You need to engage in a factual determination about the nature and timing of your obligation to the debtor and vice versa.

If your monies owing to the debtor stem from the same transaction as the debtor’s monies owed to you, you may be eligible for a process known as recoupment. While the US Bankruptcy Code does not expressly address recoupment, courts have treated it as a generally acceptable remedy for a creditor when assessing the value of its claim.

Essentially, recoupment is a determination of “the ‘just and proper liability on the main issue,’ and involves ‘no element of preference.’” (Reiter v. Cooper) Recoupment can be applied to both pre-petition claims and post-petition debts.

Due to the nature of business relationships, it’s also possible that you will owe monies to the debtor from a separate and distinct transaction than the one for which the debtor owes you money. If so, you still may be able to reduce your claim by the amount of money that you owe the debtor; however you need to engage in the setoff process. The right of setoff is created by state law, not the Bankruptcy Code, however the Code recognizes it under 11 USC § 553.

In order to apply the doctrine of setoff, the debt that you owe and the debt owed to you must both be either post-petition or pre-petition. Moreover, the debt must be mutual between you and the debtor without the involvement of a third party.

For example, if you owe money to Acme Holding Corporation while its bankrupt subsidiary Little Acme Company owes you money, you lack mutuality with the debtor and a setoff is impermissible. Of course, both the claim against the debtor and your debt need to be valid and enforceable, meaning that your obligation to the debtor is already mature and owing, rather than contingent.

Assuming both applicable state law and your contract with debtor allow for setoff, in order to engage in the setoff process against a debtor, you need to first ask the court permission to lift the automatic stay (pursuant to 11 USC § 362) to permit you to do so.

As part of the analysis of your request, the court will apply the Improvement of Position Test, which will analyze whether application of the setoff would render your claim against the debtor to be smaller at the time of setoff than it would be had the setoff been applied 90 days before the bankruptcy petition date.

Setoff is not a self-help activity! If you are not 100 percent certain whether your obligation to the debtor qualifies for a recoupment or setoff, consult an expert rather than risk court sanctions.

How essential are you?

In some circuits, the debtor, subject to court approval, is able to pay certain unsecured creditors sooner if such creditor has been deemed a critical vendor.

The debtor needs to make a special request to the court to pay critical vendors first. The court will scrutinize which creditors can receive this designation because its application violates the absolute priority rule of the Bankruptcy Code.

Typically, to be deemed a critical vendor, you have to be providing something to the debtor that it simply cannot procure elsewhere and lack of such good or service means that the debtor will be hindered in maximizing the value of its assets for all the creditors.

Moreover, in many jurisdictions, one cannot become a critical vendor unless one refuses to do further business with the debtor if you are not paid on your prepetition debts, and you agree to engage in ongoing business with the debtor if your critical vendor status is approved.

Thus, before you seek critical vendor status, be prepared to walk away from future business with the debtor if you are not approved. And get ready to do more business with the debtor if the approval is granted.

Bankruptcy and economic experts can help you make the case that what you provide to the debtor is truly unique and essential to the debtor’s maximization of the value of its assets. Uniqueness does not stem from lower pricing: Your goods and services will not be deemed unique if they are merely less expensive than a substitute.

You need to make the case that, without further goods or service from your company, the debtor will have dramatically lower value in the future and that loss will ripple through to all the creditors, ergo the debtor finding a way to engage in ongoing business with you would maximize the return for all creditors.

Timing is everything.

One of the key goals of the US Bankruptcy Code is to maximize the value of the debtor’s estate for all creditors. One way to do this is to enable debtors to continue running until they can be restructured or sold, rather than triggering a death spiral that destroys the value of the assets due to panic selling.

To encourage parties to continue to do business with a bankrupt company, the Bankruptcy Code prioritizes payment to those who continue to do business with the debtor after the bankruptcy petition has been filed. These post-petition obligations of the debtor are called “administrative claims,” and their payment is deemed to be higher priority than debts incurred by the debtor before the filing of the case.

Take a look at your own company’s relationship with the debtor: Have you continued to do business after the bankruptcy petition date? If so, you may be able to bifurcate your claim against the debtor into a post-petition claim and a pre-petition claim, with the former accorded status as an administrative claim that is paid sooner. Muster your facts and discuss with a bankruptcy expert to avail yourself of this approach.

Speed might save the day.

The creators of the modern Bankruptcy Code understood the filing of a bankruptcy petition is typically a trailing indicator of insolvency. Accordingly, the Code assumes that a debtor is actually bankrupt 90 days before the petition date. You can use this assumption to your advantage if you have provided goods to the debtor.

Outside of bankruptcy, section 2-702 of the Uniform Commercial Code enables sellers to reclaim goods provided to a buyer on credit if it is discovered that the buyer has received goods while insolvent in the seller makes a demand for reclamation of the goods within 10 days.

The Bankruptcy Code offers a similar reclamation remedy to sellers of goods (11 USC §546(c)). If you have delivered goods to a buyer has who becomes bankrupt, then it’s time to start checking your calendar because there are tight time limits on when you can make a reclamation claim.

If the debtor received the goods 45 or fewer days before the bankruptcy petition date, then you need to send the written reclamation demand to the debtor within 20 days of the bankruptcy petition date. The reclamation demand should identify the nature of the goods you are seeking to reclaim, the quality of dollar value of the goods, when the reclaimed goods were delivered, and any invoice numbers or purchase order numbers covering the goods.

The written demand should also clearly request that the identified goods be returned and that, prior to such return, the goods be segregated. A successful reclamation claim can yield you a 100 percent recovery.

Of course, what would law be without exceptions to the exception? While section 546 of the Bankruptcy Code may yield an exceptional recovery, it does not trump an interest of the debtor’s secured creditors in any goods that you delivered to the debtor. Because this remedy is limited to the return of goods, if you delivered the goods to a customer of the debtor — rather than the debtor itself — the reclamation rights may not apply.

Don’t get zapped.

Applying the proper strategy and speed can increase your recovery odds in bankruptcy; however, this does not mean you should blindly step on the gas. Bankruptcy courts are quick to defend their authority and jurisdiction and have broad powers to do so.

A failure to adhere to the procedural rules, such as unilaterally trying to affect a setoff without receiving permission from the court in advance to lift the automatic stay, can result in substantial sanctions.

You should use these strategies as talking points for developing a plan with your bankruptcy specialists to see whether your claims can be recovered, one way or another.