From the obscure and weathered fragments of antiquity to the copious and robust information exchanges of modern day, it is apparent that litigators have always exerted a dominant force upon the formation and refinement of society’s legal and cultural frameworks. This article will discuss the lives and legacies of several impactful litigators from the annals of history and the lessons we can glean from their lasting impressions.

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Cicero, born in Ancient Rome in 106 BCE, has been heralded as one of the greatest orators and writers of the Roman Republic, with an influence and reach far beyond his era. What is less known about Cicero is his career as a successful litigator. In 81 BCE, he victoriously litigated one of his most famous cases, defending a man accused of parricide (the killing of a parent). In that dispute, there was little evidence available to support Cicero’s case due to the defense’s inability to compel witnesses.

Undeterred, Cicero provided a convincing and moving argument that led to both the acquittal of the defendant and Cicero’s subsequent fame. His manner of delivery, which no doubt contributed to his triumphs as a litigator and impact as a writer, emphasized mastery, balance, and harmony of the contrasting schools of oratory expression prevailing at that time. He produced a novel, eclectic style all his own: clean simplicity beautified with decorative embellishment, ornamental indulgence tempered by unwavering purity.

Cicero was an avid student of rhythm and phraseology, believing the most persuasive and effective speakers appealed to their audiences and best transmitted their ideas by employing techniques and methods drawn from a diversity of disciplines: law, theatre, language, poetry, and philosophy. He highlighted that the abilities of a great orator consisted of “the acuteness of a logician, the wisdom of a philosopher, the language almost of poetry, the memory of lawyers, the voice of tragedians, [and] the gestures almost of the best actors…”

A testament to his brilliance and power of persuasion is his persistent relevance, which has endured millennia and still percolates in the lives of many today. Indeed, Ciceronian thought was highly revered and applied by the founding fathers of the United States, including John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, and was one of the philosophical foundations of the US Constitution.

Cicero impresses upon us that effective expression is deliberately informed and shaped by one’s exposure to and incorporation of techniques derived from a range of disciplines. This sort of education and practice permits the presenter to achieve a certain depth, texture, and flair to his or her speech and writing, capable of appealing to not only peers, a jury, or a judge in one’s own region and time, but also a universal audience across cultural, spatial, and generational spectrums.

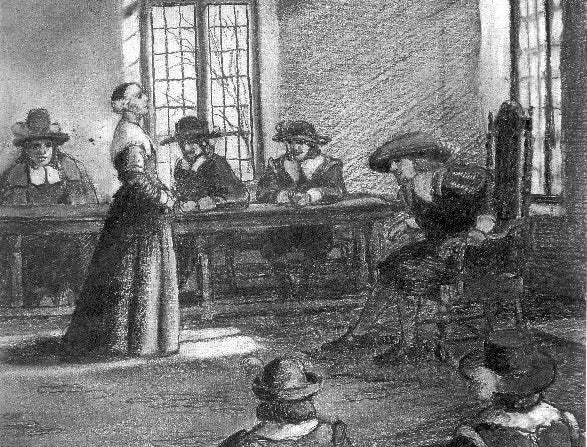

Margaret Brent

The historical record has relatively scant details about Margaret Brent, an impressive historical figure from the Colonial America era. Archives provide she was a 17th century English woman who was born around 1601 and immigrated in 1638 to what was then known as the Colony of Maryland. Although Brent had no formal training or credentialing as an attorney, she is recorded as the first woman in the American colonies to argue before the common law court and become renowned as a powerful and accomplished litigator. What Brent lacked in education, experience, and status, she made up for in courage, boldness, and diligence. She was resourceful by using what limited tools she had available to her during a time when her involvement in advocacy, although authorized, was scorned.

Brent refused to let any inadequacies — real or perceived — impede her vigorous advocacy for her own interests and that of her clients, including her brother, sister, women within the community, and even Governor Leonard Calvert of the Maryland Colony. In fact, she used what has been described as a remarkable business and legal acumen to settle one of the major disputes of her time concerning debts owed by Governor Calvert to his soldiers. The same adeptness she applied in the courtroom is attributed with resolving the conflict between those parties, preventing the mutiny of the soldiers, and saving the entire colony from war. The accounts of Brent’s outstanding initiative demonstrate that we do not have to wait until our actual or imagined deficiencies or unfairly stacked odds are eliminated to reach for and realize our goals in our practice or otherwise. It is possible to learn and win at the same time. And, in so doing, we will be a credit to our profession and community.

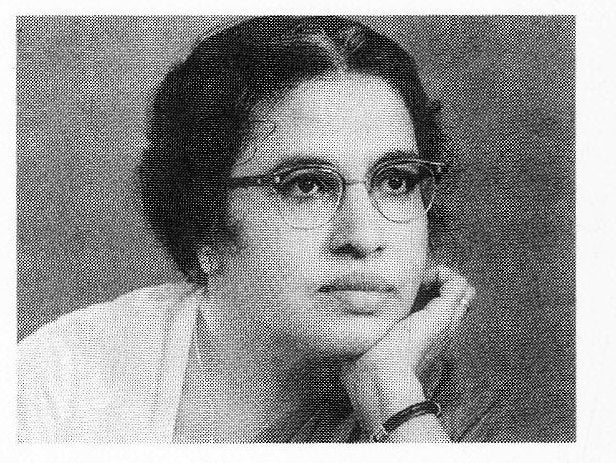

Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander

Sadie T. M. Alexander was a trailblazer whose legacy is illuminated by being the first in many achievements. Born in 1898, she went on to graduate with honors from the University of Pennsylvania in 1918. Thereafter, in 1921, she became the first African-American woman to earn a doctorate in economics, the first black woman to earn her Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania, and the second black woman to earn her Ph.D. in the United States (the first, Georgiana Simpson, earned her Ph.D. one day earlier).

She pursued law school after realizing even with her excellent credentials, she had been overlooked by potential employers. Instead of allowing disappointment to impede her advancement, she enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania School of Law and became the first African-American woman to graduate from the institution in 1927. Alexander followed the path of her father, who had been the first African-American man to earn his degree from Penn Law; she was also the first black woman to pass the Pennsylvania Bar and the first African-American to hold both a Ph.D. and a J.D.

When reflecting on her academic accomplishments, Alexander stated, “I knew well that the only way I could get that door open was to knock it down; because I knocked all of them down.” Alexander’s legal career began in partnership with her husband (also a lawyer), with whom she litigated critical civil rights cases, in addition to matters related to family and estate law. Eventually, she successfully managed her own practice after her husband became a municipal court judge.

Notably, Alexander’s intellectual zeal was married with a deep concern for her fellow man, as demonstrated by the devotion of much of her time and effort to improving the lives of others. She was the first national president of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., a predominantly black public service sorority. She was also heavily engaged with legal aid initiatives geared toward assisting lower-income African-Americans and instrumental as secretary of the National Urban League in facilitating the economic empowerment of African-Americans.

US presidents recognized and enlisted her support for various initiatives due to her extraordinary ability and commitment to the service of others: In 1948, President Harry Truman appointed her to the President’s Committee on Civil Rights; and in 1979, President Jimmy Carter named her chair of the White House Conference on Aging. She also became President of John F. Kennedy’s Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law in 1963. In addition to receiving a multitude of honorary degrees, she received the Distinguished Service Award from the University of Pennsylvania in 1980. The Philadelphia Bar Foundation, for which she served as president in 1973, named its public service center in the honor of Alexander and her husband in 1986.

Alexander’s life is a lesson that fearless temerity is often required to make positive differences in our careers, communities, and lives in general. She did not allow the injustices and obstacles of her day to embitter and discourage her intellectual and professional pursuits, nor did she use the ills of society as an excuse to suppress her empathy and turn her back on the despair of others. She persevered in boldness and kindness — qualities that made her a fierce advocate of those ignored and forgotten and a trusted counselor to some of the most prominent figures in US history. Her example highlights that giving of ourselves to uplift others can prevent us from giving up or giving out when confronted with trials and setbacks, and instead will empower us to soar to new heights on the wings of courage and compassion.

Anna Chandy

Anna Chandy (also spelled Chandi) was born in 1905 in Trivandrum, India, where she later obtained her degree from Government Law College. A criminal law barrister, she made history as both India’s first female judge (1937) and first Kerala High Court judge (1959). Chandy’s pioneering excellence involved advocating for women’s rights and opposing gender discrimination and child marriage, while endorsing widow remarriage through Shrimati, a magazine she both created and edited.

Chandy earned these professional heights by cultivating a willingness to take risks and remain focused on her aim. Earlier in her career, Chandy attempted to change the policies governing her community by running for the representative body of the Travancore state in 1930. However, her campaign for the seat failed, one of the reasons being she was the target of a successful and vicious smear and rumor scheme.

But she remained undeterred and tried again. The next time, Chandy was victorious and was elected to the Travancore state Shree Mulam Popular Assembly from 1932 to 1934. Throughout her career and life, she would encounter other difficulties, but she refused to allow them to overtake her, eventually becoming one of the first female judges in the British Empire.

Chandy’s life exemplifies that failure does not have to be the end, rather, it can be a means to an end. Indeed, the process by which we analyze unsuccessful attempts, strategies and ventures can develop and propel us to become elevated versions of ourselves, capable of triumphing over past challenges and excelling when facing new ones.

Alfred Scow

The Honorable Alfred Scow had every reason to be proud: He was the first Aboriginal person to graduate from a British Columbia law school. As the first Aboriginal lawyer to be called to the British Columbia Bar, he had a successful career as a litigator and prosecutor and eventually went on to become the first Aboriginal judge of the Provincial Court of British Columbia, presiding for 23 years. Born in 1927, Scow, of the Kwicksutaineuk-ah-kwa-mish First Nation on Vancouver Island, grew up in a world where Indigenous people of the First Nations were both prohibited from entering the legal profession and restricted from even obtaining legal representation. Moreover, Scow was of little means and struggled to complete law school when Indigenous people were finally allowed to attend. Thus, his accomplishments and prestige in the face of these obstacles and hardships were all the more deserving of accolades and praise.

However, a prominent aspect of Scow’s incredible legacy is that he was a humble and caring man who, throughout his career, valued and invited the perspectives and voices of others. He incorporated this appreciation into his practice even at the uppermost levels of his profession: prior to issuing decisions or passing judgment on the bench, he would consult with and listen to the advice of his elders. Scow’s approach is acclaimed for shifting the legal environment in British Columbia to one that was demonstrably less biased against marginalized peoples. Further, as a mentor and example in the community, he inspired later generations of Aboriginal lawyers and judges. Due to his sensitive, thoughtful, and effective wielding of authority, Scow was recognized as not only a legal giant, but also as a hero by those within and outside his Indigenous community. His example underscores that integrating and exercising humility within our practice is a critical key to achieving and performing successfully at the highest levels of our profession.