The pandemic has likely changed some consumer and business behaviors in a manner that causes direct economic impacts, ranging from shrinking office space due to expanded telecommuting to energy exploration and production companies rendered economically unviable due to plummeting fuel demand. As a result, many expect a wave of bankruptcies, which can result in a great buying opportunity for other companies seeking to expand.

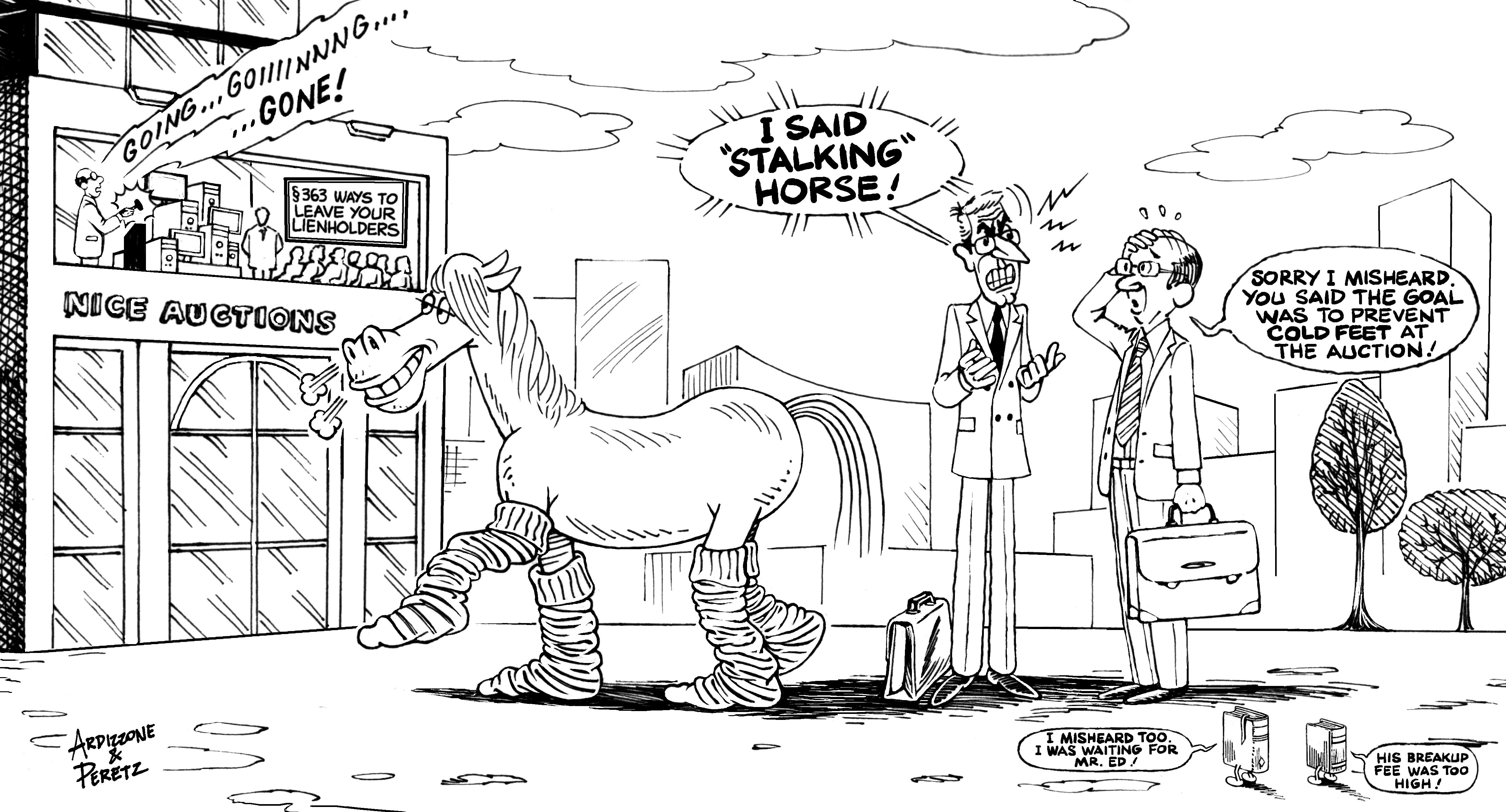

If you plan on purchasing assets is such a setting, it’s time to dig out those lucky horseshoes and learn how to become a stalking horse. By contrast, if your company is going to be the seller of assets, you need to know when to involve a stalking horse in your process and how to care and feed for such a beast so it won’t ruin your entire stable.

The corporate stalking horse

The origin of the term “stalking horse” is from the world of fowl hunting. In the 16th century, hunters discovered that birds in the wild would typically flee as soon as humans approached. However, they often were willing to tolerate the presence of horses and cattle. Taking advantage of this, hunters would approach the birds by walking on the other side of their horse, with their head and torso hidden.

Perhaps to make bankruptcy law seem more tangible or exciting, attorneys have adopted the phrase “stalking horse” to describe a mechanism designed to ensure a competitive dynamic when assets of the debtor are to be sold. Whenever an auction is to be held within a tight timeframe, such as that of a bankruptcy proceeding, there is concern that only one bidder will show up and walk away with a steal. In order to guarantee a competitive minimum price for the assets to be sold, the debtor will select a stalking horse bidder in advance of the auction.

The stalking horse bidder will make a preemptive bid for the assets in exchange for certain rights and privileges relative to subsequent bidders.

Why it’s advantageous to be a stalking horse

Stalking horse bidders regularly receive direct monetary benefits if they are not selected as the winning bidder at the end of the auction, such as breakup fees, reimbursement for expenses in preparing the room bid, and topping fees. Courts and other stakeholders may seek to curtail these benefits to the extent that they chill other bids in the auction.

For example, a topping fee (which needs to be paid when the stalking horse is outbid) or breakup fee that is disproportionately high relative to the total asset value could force other bidders to exceed the stalking horse bid by an amount so large that the deal becomes uneconomical to the next bidder. Imagine the debtor selling a used truck where the stalking horse bidder offers US$2,000 below the blue book market value, but requests a US$3,000 breakup fee.

It’s unlikely that any subsequent bidder wants to pay US$1,000 over the blue book market value. Thus, the stalking horse bidder would win the asset well under market price. Thus, the debt may seek to negotiate trimming the proposed breakup fee, perhaps to US$1,000, to ensure that a subsequent bidder would still be motivated to bid because the price would still be at or below market.

There can also be substantial informational benefits to being the stalking horse bidder because you may have more time than other bidders to engage in due diligence about the assets for sale. Auctions of a debtor’s assets often occur in a compressed timeframe that can inhibit the typical research that a buyer would prefer before submitting a bid.

By engaging with the debtor and their counsel sooner before the auction, the stalking horse bidder has more time for research. Thorough due diligence is particularly important when purchasing an asset from a bankrupt company, because recourse to the seller is unlikely if unexpected liabilities are found after closing of the sale.

Through prolonged exposure to the debtor, in preparation for the stalking horse bid itself, such a bidder also has an opportunity to build deeper relationships with the management team that may accompany the purchase of an asset. Depending on what’s being sold, the company team may represent a substantial portion of the value being purchased.

Sometimes deal structures matter as much as the purchase price itself. For example, a high purchase price based on an earn out structure (where the ultimate amount paid can be reduced if the acquired business does not hit certain revenue or earnings targets) may be far less risky than a lower purchase price that must be definitively paid, regardless of performance of the assets purchased.

The stalking horse bidder can negotiate with the debtor about the contract terms and structure for the acquisition, and may also request the inclusion or exclusion of certain bidding procedures as part of the subsequent auction.

Not every horse wins the race

Horses may be a great form of transportation across a pasture, but less helpful when facing a steep cliff or an unexpected ravine. Like uncharted topography itself, bankruptcies can present many surprises that can make the stalking horse wish it had not moved to the head of the pack.

When stalking horse bidders negotiate expense reimbursement, for example, the debtor and other stakeholders (e.g., the creditors committee) may push for an absolute cap on such expenses. Due to the narrow time frames when preparing for an auction and the possibility that the debtor’s records related to the assets being sold are in disarray, the stalking horse bidder’s expenses conducting diligence and preparing a bid may exceed this reimbursement cap. If, in the end, the stalking horse bidder is not the winner of the auction, it will have lost money due to insufficient expense reimbursement.

A stalking horse bidder may also end up overpaying for the asset being sold. Typically, buyers want to wait as long as possible before purchasing an asset in case the market value of the asset changes. The stalking horse bidder cannot wait as long before placing its bid. If the value of the underlying asset being sold tumbles between the commitment date of the stalking horse bidder and the actual auction, the stalking horse bidder will still be required to close the transaction at a price that is likely above the market value at the time of the auction.

Stalking horse bidders are typically required to make a representation that they have sufficient funds to close the transaction in a timely manner if they are selected as the winning bidder and put up a deposit representing a percentage of the purchase price. If, after a series of back-and-forth bids at the ultimate auction, the stalking horse cannot kindly pull together the rest of the financing to close the transaction, it may lose its deposit.

Bidding money that you already spent

For secured creditors in bankruptcy, section 363(k) of the Bankruptcy Code enables them to bid for a company’s assets and “pay” using the money already owed to the creditor. In the event that a secured creditor does not want on the underlying asset, they may be willing to sell their secured claim against the debtor to third party for a discount and the third party can use that credit as a stalking horse bidder.

For example, a bank may have long a debtor US$200,000 secured by construction equipment, however the bank does not want to own construction equipment at the end of the day. Instead, the bank needs cold, hard cash. An opportunistic third party that wants the construction equipment may convince the bank to sell its US$200,000 claim at a substantial discount (e.g., US$100,000) in exchange for prompt payment of cash to the bank.

The third party would then position itself as the stalking horse bidder by credit bidding the full US$200,000 claim that it purchased from the bank. If the third party ends up as the winner of the auction, then it has essentially paid US$100,000 for the underlying asset.

If someone else ends up as the winning bidder (which would require a bid exceeding US$200,000), then the proceeds from the auction would be used to repay the secured creditor, viz. the third-party stalking horse that bought the claims from the bank. This would yield a handsome financial return to the stalking horse: repayment of the full US$200,000 are claim that the stalking horse had purchased from the original creditor, the bank, for only US$100,000.

Beware of the endgame of opportunistic wonders

Certain lenders specialize in loaning money to bankrupt companies, providing so-called DIP (Debtor In Possession) financing, with an underlying plan to either receive an outsized return or to take over the assets of the debtor in a below market price.

When negotiating with a prospective DIP lender, the debtor and other stakeholders need to be wary of penalties and fees hidden in the loan agreement which penalize the sale of the underlying assets to anyone other than the DIP lender. Akin to a disproportionately high breakup fee, these inclusion of such terms in a financing agreement can have a chilling effect on other bidders for the debtor’s assets.

Balancing business needs and legal risk

As the in-house counsel, your colleagues are looking for your advice on where they may be taking on too many risks when compared to the likely reward. If your team is evaluating putting together a stalking horse bid, then you need to have a rapid due diligence checklist in hand and put potential values on the extra risks you may incur by being the first bidder.

Consider how much less the stalking horse bidder will bid compared to subsequent bidders: Does the price difference outweigh your valuation of the potential risks? Be ready to explain to your colleagues both the potential cost of the risks and their probabilities based on historic data.