CHEAT SHEET

- A unique M&A challenge. Trade secrets are often left to the end of the due diligence process, due to their confidential nature.

- A double-edged sword. If a seller discloses a trade secret late in the negotiations, there may not be sufficient time to evaluate the asset; however, the seller is wary of disclosing early and divulging confidential information in a deal that may not proceed.

- Unclear valuations. Some trade secrets have subjective economic value. Prospective buyers should analyze the relative value of the trade secret and determine its uniqueness and availability.

- Err on the side of caution. Prospective buyers should consider the possibility that the deal will not close, and limit the number of due diligence team members evaluating the trade secret.

Trade secrets have long been a part of the intellectual property strategy that companies use to protect market share. Popular brands use trade secrets to create allure for their products. Often imitated, but never duplicated, the Coca-Cola formula, Colonel Sanders’ chicken recipe and the McDonalds special sauce are just a few trade secrets that have caught the attention of the consumer public. Others — Google’s search algorithm, the process for making Cellophane, the formula for WD-40 — have spurred entire industries.

Trade secrets and corporate know-how are often the differentiator between success and failure in the marketplace. Regardless of size and whether they realize it or not, every company has information that they guard. Whether it’s the secret formula or a customer list, it can be the element that gives the company a competitive edge.

Trade secrets generally take a back seat to the federally mandated patents, trademarks and copyrights, but trade secrets are often pulled out when other intellectual assets fail. Companies can rely on trade secrets when, whether through accident or by design, the company has kept the information confidential. Trade secrets are often not protected through a formal trade secret program and, even when they are, definition of the technical information that forms the basis for the trade secret can be ambiguous.

In the area of mergers and acquisitions, trade secrets can provide unique challenges to the due diligence team evaluating the target company. Regardless of whether a target company has strategically and formally protected these assets, trade secrets are an inevitable part of the sale or purchase of any company, big or small. However, unless the seller touts a trade secret or confidential know-how, trade secrets are often left until the end of any due diligence process, if they are considered at all. This breakdown in consideration is not based on a negative view of trade secrets as assets; it stems from a more practical problem. Since trade secrets are confidential information, sellers often restrict the disclosure of this information until the deal is very close to completion. Likewise, in companies without a formal trade secret program, acquiring knowledge that the asset even exists can prove difficult.

IP value

In a large acquisition with significant intellectual property assets, the buyer’s team will usually begin by focusing on the publically available assets, specifically patents, trademarks and copyrights. Because information about these assets can be pulled from commercial databases, the buyer can begin an analysis without the need for specific disclosure from the seller. To determine the value attributable to the intellectual property (IP), a prospective buyer sets out to understand its scope and any limitations that accompany the deal. What the buyer can find challenging with cataloged assets like patents, trademarks or copyrights may seem insurmountable when the asset is confidential information.

Confidentiality obligations make trade secrets hard to assess during typical due diligence. The seller wants to hold the confidential information as long as possible, while the buyer would prefer the information as soon as possible. The timing of disclosure can be a double-edged sword. If the seller discloses late, the time needed to do a full evaluation may be impractical. However, if the seller discloses too early, the prospective buyer can find himself in possession of confidential information or trade secrets that might restrict his actions should the deal not go forward. This is a particularly important consideration when the buyer and seller are engaged in the same business enterprise, which is often the case.

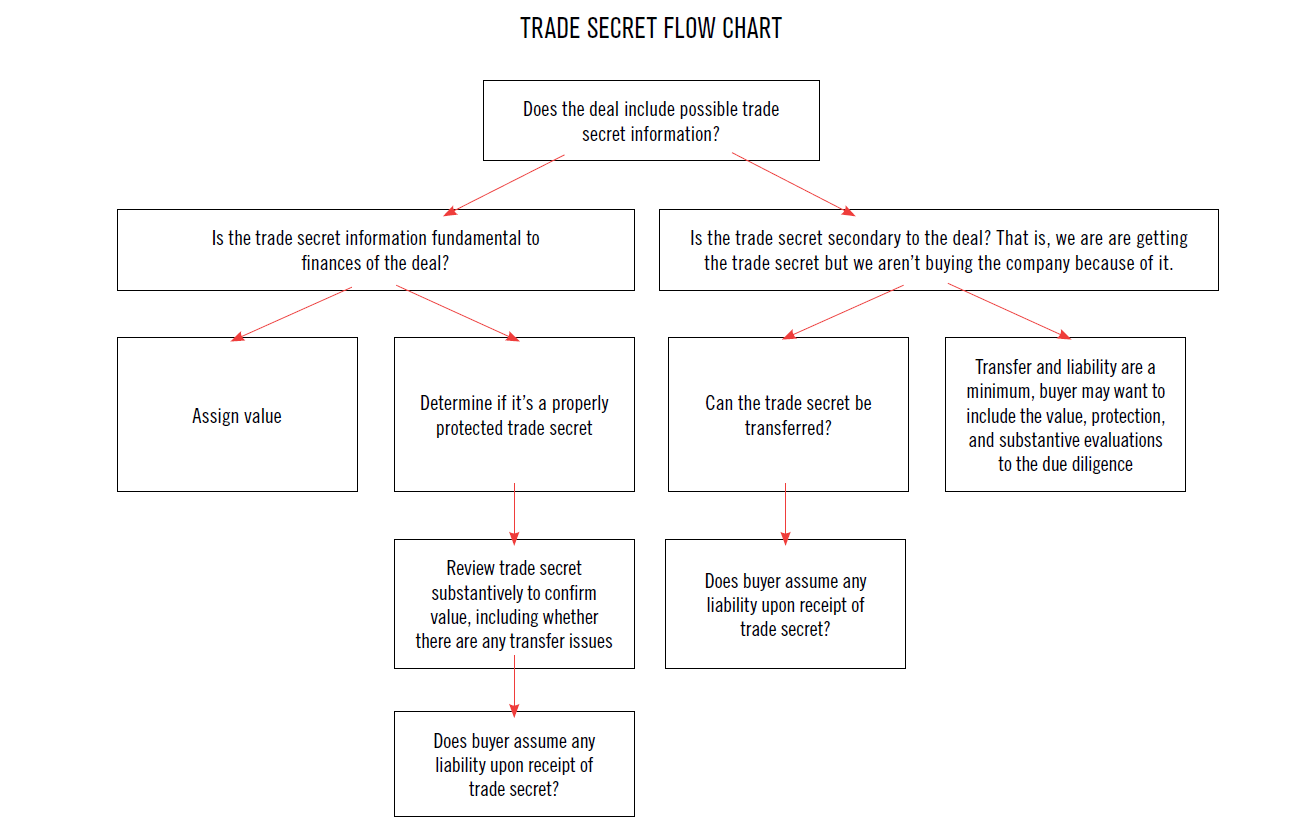

If possible, before undertaking substantive consideration of a target’s trade secrets, the relative value of the trade secret to the deal should be considered. If the trade secret has a material financial impact on the deal, it should be disclosed during financial negotiations so that a value may be assigned. When trade secret disclosure occurs in this early stage, the buyer should always limit the disclosure of the trade secret to as few people as possible. A good choice may be to a single member of the due diligence team, for example, intellectual property counsel.

If however the buyer is basing the purchase on other assets, and the trade secrets are secondary to the deal, due diligence may still be necessary, but the type of analysis the buyer would carry out differs. Rather than looking at the value of the trade secret or the policies that are in place to protect it, the due diligence team would instead focus on whether the trade secret brings with it any third-party issues or other liabilities, and whether any steps are needed to preserve the value of the trade secret during the transfer process. If, for example, the policies and practices around protection of the trade secret are inadequate, but transfer of the asset will not be jeopardized, no action may need to be taken before the deal closes. There will be ample time after the deal closes to update policies and practices.

Trade secrets

If one or more trade secrets are an integral part of the deal, the first thing to consider is whether the information that is being called a trade secret is, in fact, a trade secret. Often the term “trade secret” is used broadly to refer to confidential or proprietary information or know-how; however, just because something is confidential doesn’t make it a trade secret.

The term “trade secret,” has a specific meaning in the United States, which derives from the Supreme Court’s decision in Kewanee Oil Co. v. Bicron Corp.;1 the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (the “UTSA”), which has been adopted by 47 states and the District of Columbia; and the federal Economic Espionage Act of 1996.

A trade secret, under the UTSA and the Economic Espionage Act, is defined as:

“[i]nformation, including a formula, pattern, compilation, program, device, method, technique or process, that (1) derives independent economic value, actual or potential, from not being generally known to the public or to other persons who can obtain economic value from its disclosure or use; and (2) is the subject of efforts that are reasonable under the circumstances to maintain its secrecy.”

Trade secrets are a subset of confidential information. A trade secret is confidential information that provides the company with a competitive advantage. Confidential information that does not have an independent economic value won’t rise to the level of a trade secret and cannot be misappropriated. Put another way, while subsequent disclosure of confidential information that is not a trade secret may be susceptible to a claim for breach of a confidentiality agreement, actual or implied, it will not be the subject of a misappropriation claim.

Whether something is a trade secret requires a factual analysis of whether the asset has independent economic value to the discloser. Consider the following examples. Company A is buying company B, an insurance company. Company B’s customer list ends up in the hands of Company A and it is a compilation of all of their customer’s names and addresses. Would this be a trade secret? Many courts have said it is not a trade secret if it only contains names and addresses that would be readily available public information. By contrast, consider Company A buying company B, the same insurance company, but this time Company B’s customer list includes not only names and addresses, but information on prior policies, personal history data, location and descriptions of insured property, renewal and termination dates. Such a customer list has been held to constitute a trade secret. The rationale is that the second list is not merely public information and had been developed over a long period of time to give a competitive advantage.

The due diligence process is much easier if the target company has a trade secret program or policy. Such a program should provide some specificity as to what the company believes constitutes its trade secrets. It should be noted, however, that delineating the exact nature of trade secrets can be difficult for the company that owns them and even more difficult for a potential purchaser.

For example, in Purchasing Power LLC v. Bluestem Brands2, a failed merger discussion resulted in Bluestem allegedly being in possession of trade secrets belonging to Purchasing Power. The court found for Bluestem on summary judgment, finding that Purchasing Power didn’t adequately identify its trade secret, despite the fact that Purchasing Power identified 12 different categories of information that it believed Bluestem had misappropriated. The court found that “[b]road information categories are not sufficient”3 to identify and prove ownership of a trade secret.

A target company’s policy for handling trade secrets is not, alone, sufficient to conclude that the trade secrets were adequately protected. Actual protection is derived from a combination of good policy and strong enforcement. A trade secret program could be stellar, but if it’s not enforced properly, it may have no ability to actually protect the trade secret from disclosure.

Courts generally look to see if the information that is being asserted as a trade secret is currently confidential, whether it has been kept confidential inside the company, and whether third-party access to the information has been controlled. Whether the trade secret was subject to a written policy or not, the analysis would be similar. A prospective buyer would want to know how the trade secret was handled inside the company and out.

Typical questions would include:

- Are you aware of any instances when the trade secret information was disclosed to a third party without a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) or confidentiality agreement?

- Was the number of your employees who had access to the information limited?

- How was the information stored? If it includes electronic information, what security measures were taken to prevent access to the information?

- How did third-party access the information, if at all? To what extent is it controlled internally? Must guests be escorted?

- If it has been shared with third parties under an NDA, was the information left with the third party, destroyed by the third party, or returned?

- To the extent information was destroyed, how was it destroyed? Shredded? Were computers scrubbed before being released or destroyed?

Nclosure Inc. v. Block and Co.4 illustrates that a confidentiality agreement may not be dispositive in determining whether a trade secret had been reasonably protected. Nclosure, an industrial design firm, worked with Block and Co. to develop metal cases for electronic tablets. To that end, the two companies entered into a confidentiality agreement, and Nclosure shared its designs with Block and Co. When Nclosure and Block and Co. ended their relationship, Block and Co. introduced its own metal tablet cover, and Nclosure sued, alleging misappropriation of trade secrets. The 7th Circuit found in favor of Block and Co., holding that Nclosure failed to take reasonable measures to protect its confidential trade secrets. The court acknowledged that the parties had signed a confidentiality agreement, but found it significant that Nclosure had taken virtually no other step to protect the confidentiality of its designs. The court noted that the designs had not been marked as confidential, had not been kept under lock and key, and had not been subject to a confidentiality agreement for all other third parties who viewed the designs.5

Special care should be taken if the trade secret asset has already been shared with third parties, for example, a contractor or a joint venture partner. If such a case, the relationship between the seller and the third party in possession of the trade secret will need to be assessed. The buyer will want to assure that any contracts between the seller and the third party include appropriate non-disclosure agreements, preferably specifically addressing handling of trade secrets. The buyer will also want to know whether those relationships will transfer to the new company, and if not, if there is a mechanism for the third party to return any confidential information it has to the seller.

1 416 U.S. 470 (1974)(holding that the patent law does not pre-empt the states from having trade secret laws).

2 22 F. Supp.3d 1035, (N.D. Ga. 2014).

3 Id. at 1313.

4 77 F.3d 598, (7th Cir. 2014).

5 Id. at 602.

Valuing a trade secret

At this point in the buyer’s due diligence, the analysis has only identified whether the trade secret is a viable asset under trade secret law. It provides no information on the substantive or technical value of the trade secret information. As with other forms of IP, valuing a trade secret can be very difficult. If the business team isn’t inherently valuing the trade secret in the purchase price and a numeric valuation of the trade secret is required, it may be useful to engage a valuation expert with the appropriate economic background.

Even if an economic valuation is not required, a prospective buyer should nonetheless undertake an analysis of the relative value of the trade secret. Such an analysis might include a review of the trade secret information to see if it is susceptible to reverse engineering or independent discovery. A search may also be carried out to determine whether the trade-secreted information is available from other sources. If it is available, it doesn’t mean that the trade secret is valueless, but the value may be diminished. The value of the trade secret might be in the use of something known, but such use isn’t readily apparent in the industry. If it makes a product better or cheaper, for example, the trade secret would still have value. However, the value of the trade secret will be eroded if the information is already available or if the commercial product can be easily reverse engineered. Depending on the importance of the trade secret to the deal, the economics of the deal may be affected.

Personnel considerations

When considering the actual value of the trade secret, it is also necessary to consider the seller’s ability to effectively transfer the trade secret to the buyer. Often trade secrets are known by a limited number of personnel, which, as discussed above, is not a bad thing when trying to prevent disclosure.

Personnel can become an issue in the effective transfer of a confidential asset. Even in an acquisition where the entire company is being purchased, unless key personnel are bound by contract, they are generally not obligated to stay with the new company (e.g., the merged company or the acquiring company). If the effective transfer of the trade secret requires personnel from the seller, be sure appropriate contracts are in place before the deal closes. Depending on the circumstances, it may be necessary to consider the non-disclosure agreements and the non-compete agreements that the seller has with key personnel who are in possession of the trade secrets to assure the information will not become available for use by a competitor, should the individual chose to leave the new company.

Due diligence is an imperfect process. Typical due diligence analysis doesn’t always fully develop the issues surrounding key personnel, leading to this area being overlooked, or given very little attention. In the area of trade secrets, personnel are key and the majority of trade secret misappropriation cases are waged between employers and their former employees.

If the transaction is the purchase of a start-up company or small business, particularly one in which the personnel are not going to the new company, the buyer has the added issue of the trade secret being concurrently sold by the start-up and retained by the principals. And while the principals may agree to not disclose the trade secret after the purchase, they cannot separate the information they transferred from what they know, so subsequent developments by the principals can be a concern and should be accounted for in the deal documents.

When considering the transfer of trade secrets, it is important to understand where and how the trade secret will be used in the new company. If a large company is buying a small company whose primary asset is a trade secret, the buyer may have a number of locations in the United States, or all over the world. In many common law jurisdictions of the world, trade secrets are a right in equity rather than a right in property. In the United States, trade secrets are governed by state law. The buyer’s due diligence team will want to know if the trade secrets are to be used in multiple locations, different states, or outside the United States. Depending upon the laws of the various jurisdictions, there may be differences in the measures needed to maintain the trade secret. Alternatively, if the use is to be quite wide, it may be very difficult to maintain the information as a trade secret and the buyer may want to consider whether the information is protectable in a different manner, e.g., is it patentable?

Practical tips

To protect himself, a prospective buyer should always consider the possibility that the deal will not close. The prospective buyer should limit the number of people on the due diligence team who will be in possession of the trade secret. Preferably, technical personnel who work with the same type of technology as the buyer will not be part of the review team, at least not the initial review team. Often a prospective buyer wants the technology evaluated by the personnel in the buyer’s business who will best understand the value of the trade secret. However, if the deal doesn’t close, those individuals will be the ones in the best position to inadvertently take advantage of the trade secret, leading to potential misappropriation. It is impossible for an employee to unlearn the trade secret and, whether intentional of not, it could influence his subsequent developments. If the trade secret is particularly sensitive, consider having the information shared only with the outside due diligence team until certain milestones in the deal are achieved and the parties agree that the disclosure of the trade secrets is appropriate. If the deal fails to close, the potential of employees within the buyer’s organization being in possession of the trade secret is lessened.

Finally, as with patents, trade secrets can be the subject of an antitrust challenge. In many instances, the buyer and seller are engaged in the same business. If the disclosure and use of the trade secret would substantially lessen competition, an antitrust analysis should be undertaken. If the deal is subject to a Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) filing (which is required for all deals of a value of somewhere around $75 million and above), and there is any concern that the acquisition of the trade secret is problematic, then it should be addressed with the DOJ through the HSR process. The counsel handling the deal should have antitrust counsel to assist with this.

Conclusion

Trade secret misappropriation is estimated to be as high as one to three percent of the US gross domestic product.6 An early understanding of the key players, the buyer’s intended uses of the trade secrets, and the seller’s policies and positions regarding the trade secrets is fundamental to structuring the correct questions to undertake a thorough and informative due diligence process. A thorough trade secret due diligence can inform the economics of the deal, identify any third party risks, and even minimize the opportunities for post-acquisition misappropriation of trade secrets.

6 Economic Impact of Trade Secret Theft: A framework for companies to safeguard trade secrets and mitigate potential threats. Create.org and PWC.com, February 2014.