CHEAT SHEET

- That which infringes if later, anticipates if earlier. Learn the spirit and meaning of this seemingly incoherent principle and you’re well on your way to understanding patent law.

- Be the dominant patent. Whatever your company’s field, strive hold the dominant patent, but don’t procure a patent so broad and so encompassing that it is anticipated by what came before.

- Claim charts are at the heart of patent law. Claim charts are a convenient and effective means for analyzing and presenting information regarding a patent claim.

- The devil is in the details. There is more to patent law than axioms, but these three are a good start.

Sometimes, there is a disconnect between certain truths patent attorneys hold dear and what corporate counsel understand about patents. If corporate counsel do not clearly understand what patent attorneys tell them, the result can be frustration, poor patent quality, unnecessarily high patent costs, litigation missteps or misconceptions that could adversely affect business decisions.

In an attempt to close the gap between how patent attorneys think and what corporate counsel understand, we will discuss the following three patent law principles:

- That which infringes if later, anticipates if earlier;

- Be the dominant patent (but don’t forget the first principle); and

- Claim charts are at the heart of patent law and embody the first two principles.

Can all of patent law be distilled into just three main principles? No. But these three principles cover a lot of patent law ground and are at the heart of our patent system. Understanding them will enable you to make better patent decisions, to better manage your patent portfolio, and to better understand your patent attorney.

Principle No. 1: That which infringes if later, anticipates if earlier

Memorize this little gem of a saying and impress a patent attorney at a cocktail party. Understand it well and you are on way to understanding quite a bit of patent law.

Our first principle is time based and requires an understanding of infringement and anticipation. But, no worry, you’ll soon understand it because when you first heard about inventions and patents when you were a child, you got the idea inherently. The problem is that the more you learned about patents throughout your career you likely lost some of this original understanding.

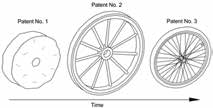

Let’s use the following scenario as a simple example running through all three of our principles. First, someone long ago invented the basic wheel. Carved from stone, it was round and maybe had a central hole for an axle. Think of the comic strip BC by Johnny Hart.

As the invention evolved, someone made a wooden wagon wheel with a central hub for the axle, a wooden rim capped with a metal band, and spokes between the hub and the axle. Think of Little House on the Prairie. Still later in time, someone came up with an inflatable tire mounted on a rim like a bicycle tire.

In time then, the wheel development looks like this:

To state the obvious, you already know that all three of these wheels are inventions and that all three could be patented.

So what does “that which infringes if later, anticipates if earlier” mean? First, pick the patent. Let’s choose the patent (Patent No. 1) for the rock wheel (and assume Patent No. 1 broadly covers all wheels). Second, pick the “that.” Here we will choose the wagon wheel. Then, the first principle reads in part: The wagon wheel infringes (violates) the first (rock wheel) patent if the wagon wheel is later in time. It is later in time. Simple, right?

The “anticipates if earlier” part of the first principle requires us to understand “anticipation” in patent law terms. Although it is not really this easy, for our purposes let’s say “anticipates” means “it came before or was earlier.” If you are patent savvy you know many exceptions to our oversimplification but let’s leave them out for our discussion. So, if “it” (a patent, product, etc.) came before, then a given invention is not new (or is obvious). And, if an “invention” is not new, it cannot be patented (or if a patent is granted and it is proven to not be new, then the patent is invalid).

Applied to our example, if we imagine the wagon wheel came before the rock wheel in time, then the patent (Patent No. 1) for the rock wheel is invalid because it is anticipated by the wagon wheel.

The complete first principle as applied to our scenario is then as follows: The wagon wheel infringes (violates) the patent for the rock wheel if the wagon wheel is after the rock wheel in time but the rock wheel patent is anticipated or invalidated by the wagon wheel if the wagon wheel came before the rock wheel patent in time.

Why? Well it is simple. If Patent No. 1 covers all wheels, then the later wagon wheel violates the first wheel patent. But if the wagon wheel is before the invention of the rock wheel, then the rock wheel is not new, and therefore it is not an invention and is not patentable. Patent attorneys call the wagon wheel in the latter scenario “prior art.”

You can also play this game by picking the patent (No. 2) for the wagon wheel. Suppose it covers the wagon wheel and also the bicycle tire. But, suppose the patent for the wagon wheel also covers the first rock wheel. What does the first principle say? The bicycle tire infringes the wagon wheel patent because the bicycle tire is later in time. But the wagon wheel patent is anticipated (and thus invalid and cannot be infringed) because it also impermissibly covers the earlier in time rock wheel. This is exactly how the first principle usually plays out: A later product infringes a given patent but the patent also covers a piece of prior art and thus the patent is invalid.

So, basically, you cannot patent something that is old (not an invention) and if you do your patent could be invalidated. But, you probably already knew that.

The real reason the first principle is so important is because of a corollary to the first principle. The corollary is that valid patents for a given technology are necessarily more restrictive or narrow over time. This corollary is key in business because a broad patent covering not only your company’s invention but also later modifications made to it by competitors are valuable while, conversely, narrower patents which only cover exactly what your engineers and scientists constructed are less valuable. At the same time, if your patent is too broad, it might, under the first principle, be anticipated and thus worthless.

This brings us to our second principle.

Principle No. 2: Be the dominant patent (but don’t forget the first principle)

What is a dominant patent? Let’s refer back to our example. If the first patent covers all wheels, then it is valuable. Pretend that the rock wheel patent is still in force when the wagon wheel and bicycle tire are developed. The value of the first patent is high because the wagon wheel and bicycle tire constitute infringements. So too might new uses for wheels, whether as a pulley, grinding wheel, water wheel or a baseball pitching machine where two spaced wheels propel the baseball toward the batter.

If the first patent was narrower, limited perhaps to only wheels made of rock, then it would be less valuable because the wagon wheel, the bicycle tire and other wheel examples would not infringe the first patent.

Now don’t forget that the wagon wheel and the bicycle tire also constitute inventions (irrespective of what the first patent “covers”). That is why we see in our illustration Patent Nos. 2 and 3. Some call these “improvement patents.” Patent No. 1 is said to “dominate” Patent Nos. 2 and 3. That is one reason someone might invent something, patent it and not be able to sell it because it violates a prior dominant patent.

Now the truth is, of course, that even if we imagine there was Patent No. 1 for the rock wheel, Patent No. 1 expired well before the wagon wheel was designed and even that patent (Patent No. 2) expired long before the bicycle tire was developed. Still, shortly after most major technological breakthroughs, there are usually refinements, additions and enhancements. For example, there are a lot of patents covering bicycle tires and there will be a lot more as technology progresses. Within each technological sub-group (treads, tire material, spoke design, etc.), there will be dominant patents. Whatever your company’s field, strive to be the dominant patent but don’t procure a patent so broad and so encompassing that it is an anticipated by what came before.

The issue of whether or not a company has or could procure a dominant patent affects the patent budget, is important in due diligence investigations, and can affect the price of licensing deals. For example, a company might wisely decide to build a substantial foreign patent portfolio if the patent is dominant but forego expensive foreign patent application filing and maintenance costs if a dominant patent cannot be procured.

Let’s now keep the first and second principles in mind as we explore claims charts with a new example: Two, three and four bladed shaving razors. We’ll return to the wheel illustration as well.

Principle No. 3: Claim charts are at the heart of patent law and embody the first two principles

Our new example is based on a real case but we have changed, ignored and simplified some of the facts to make your lives easier.

The Gillette Company patented its “Mach 3” razor: a razor with three or more blades having a “progressive blade exposure” which means the first blade stuck out a little less than the second blade which stuck out a little bit less that the third blade. The first page of the actual Gillette patent is shown here:

The blades are annotated by the reference nos. 11, 12 and 13 and in the figure where the progressive blade exposure is shown.

Later, Schick came out with its “Quattro” razor, which has four progressive blades. Gillette sued Schick and Schick primarily defended itself using the first principle (that which infringes if later, anticipates if earlier). To do so, Schick had to uncover razors (or patents for razors) prior to Gillette’s “Mach 3” razor. Schick found that there were three bladed razors without progressive blade exposure prior to the invention of the Gillette “Mach 3” razor and there were also two bladed razors with progressive blade exposures prior to the “Mach 3” razor.

Using the first principle, then, Schick’s basic defense was that if Schick’s “Quattro” four bladed razor with progressive blade exposure constitutes an infringement of the Gillette patent for a three or more bladed razor with progressive blade exposure, then Gillette’s patent is anticipated (invalid) in light of prior patents disclosing three bladed razors and the known idea of progressive blade exposures in two bladed razors.

Before we can construct Schick’s claims chart we need to understand patent claims. We haven’t talked yet specifically about patent claims but in patent law “the name of the game is the claim.” Any given patent has a lot of information in it but only those numbered paragraphs at the end of the patent really matter. In those numbered paragraphs are claims that describe what the patent covers or what is allegedly novel and what combination of things constitutes an infringement of the patent. More particularly, then, our first principle is really that which infringes a patent claim if later, anticipates the claim if earlier and our second principle is really own the dominant patent claim.

Claim charts are used to make sense of a patent claim in a given scenario. Many federal district courts have local rules that even require the parties to generate claim charts for the judge. In our Gillette v. Schick scenario, Gillette’s claim chart might appear as follows:

| GILLETTE’S PATENT CLAIM | SCHICK QUATTRO RAZOR |

|---|---|

| At least three blades | The Quattro razor has four blades. Thus, the Quattro razor has at least three blades. |

| Progressive blade exposure | The Quattro razor blades have a progressive exposure. |

Schick’s claim chart, in turn, might look like this.

| GILLETTE’S PATENT CLAIM | PRIOR TWO BLADED RAZORS | PRIOR TWO BLADED RAZORS |

|---|---|---|

| At least three blades | These prior razors have three blades | |

| Progressive blade exposure | These prior razors had blades with progressive exposure. |

Thus, Gillette argues, “that which infringes if later” while Schick argues that it “is invalid if earlier.” Most patent infringement lawsuits, at their heart, are about such contentions by the parties.

Was Gillette’s position that it held a dominant patent for three or more blades with progressive blade exposure correct? Or was Schick correct that such an idea was anticipated by what came before it? Unfortunately, we may never know because, like most cases, it was settled. But, it doesn’t matter for our purposes. The case simply introduces us to claim charts. They are an easier way to understand patent law and the first two principles in any given scenario.

Let’s now imagine it’s your company’s patent claim at issue and it recites three features (components, manufacturing steps, materials, molecules, whatever) we’ll generically refer to as A, B and C. Patent attorneys call A, B and C “limitations” or “elements.”

Your patent claim is valid (not “anticipated”) and covers a competitor’s later product under the first principle if the following claim chart can be constructed and is true:

| PRIOR ART | YOUR PATENT CLAIM | COMPETITOR LATER IN TIME |

|---|---|---|

| A | A | A |

| B | B | B |

| C | C | |

| D |

That which infringes if later (the competitor’s product including at least components A, B, C per your patent claim) is not anticipated by the prior art (which does not disclose C per your patent claim). Your patent claim is dominant as well at least for the combination of A, B and C since it would cover the later combinations A, B, C, D, and E; A, B, C, and E; and the like.

Your patent claim covers a competitor but is invalid (anticipated) under the first principle if the following claim chart is true:

| PRIOR ART | YOUR PATENT CLAIM | COMPETITOR LATER IN TIME |

|---|---|---|

| A | A | A |

| B | B | B |

| C | C | C |

| D |

All of this really leads us to the worst-case scenario in patents. This particular scenario worries patent attorneys and will also frustrate corporate counsel. That is, your patent could have been valid under the first principle but is not dominant under the second principle. In that worst-case scenario, the claim chart would look like this:

| PRIOR ART | YOUR PATENT CLAIM | COMPETITOR LATER IN TIME |

|---|---|---|

| A | A | A |

| B | B | B |

| C | D |

Here your patent claim is narrower than it needs to be. It would have been valid under the first principle had it recited A, B, D (or A, B, X where C and D are species of X) and the claim would have covered what the competitor engineered but, since your claim is limited to the recitation of A, B, C and the competitor’s product does not include C (the competitor chose D instead), the competitor is not infringing your claim. In patent speak this means the competitor has “designed around” your patent. Your patent is not dominant and is low in value. Again, there are a lot of assumptions made here but hopefully you now begin to get the idea.

To drive it home, look back at our rock, wagon and bicycle tire example. Suppose your company is the one that developed the wagon wheel. There are three possible ways of claiming this wheel in your patent:

- A wheel.

- A wooden hub, a wooden rim, spaced wooden spokes between the wooden hub and the wooden rim, and a metal band about the wooden rim.

- A hub, a rim and spaced spokes between the rim and hub.

Now, you can easily apply the first and second principles to these claim choices above by visualizing claim charts. Patent claim No. 1 is infringed by the bicycle tire (and a lot more) but it is invalid (and thus probably worthless) due to the rock wheel coming before it.

Claim 2 is valid (the earlier rock wheel has no wooden hub, rim, spokes or metal band) but claim 2 is narrow and less valuable because it does not cover the bicycle wheel. Claim 2 is not the dominant patent in its field. Patent attorneys call this “under claiming.” It is our worst-case scenario.

Patent claim 3 is just right. It’s valid in light of what came before (the rock wheel) and it covers the bicycle wheel (and also may be even water wheels and more).

Claim construction

Besides infringement and validity, another big issue in most patent cases is claim construction — a federal district court judge deciding what the patent claim language really means. In the Gillette v. Schick case, a key claim construction issue was whether or not Gillette’s patent claims covered four bladed razors or instead were limited to three bladed razors. The district court judge ruled Gillette’s patent was limited to three bladed razors. Thus, the Schick Quattro razor with four blades could not infringe Gillette’s patent. On appeal, however, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (in a 2-1 decision) reversed the district court judge.

Thus, our three principles constitute the essence of patent law. Valuable patents capture competitor’s products but are also valid (or at least not subject to an easy validity attack) and are dominant to the maximum extent possible. Claim charts can be used in drafting patents, dealing with rejections by the patent office, in infringement studies and lawsuits, to quickly analyze validity studies and defenses, and in the valuation of patents.

There is a lot more to patent law than just these three principles. But most of the rest is just the details. Patent attorneys think in terms of claims charts and in terms of the first two principles. If you can too, any disconnect between you and your patent attorney should diminish.

Further Reading

1 Peters v. Active Mfg., 21 F.319 (W.D. Ohio 1884) (affirmed and quoted in 129 US 530 (1889).

2 See the motion picture Caddyshack (Ty Webb (Chevy Chase) to Danny Noonan (Michael O’Keefe)).

3 “Better, cheaper, faster: pick any two” original author unknown

4 In re Hiniker Co., 150 F3d 1362, 1369 (Fed Cir 1998).

5 The Gillette Company v. Energizer Holdings, Inc., 405 F.3d 1367 (2005).