You have been hearing about computers beating the World Chess Champion, and even a world-famous master of Go, the Chinese strategy game.

Does this mean that computers will soon replace lawyers?

The short answer is “No.”

Is it because lawyers are smarter than chess and Go masters? No, it’s because an understanding of the broader context is an essential human expert task for determining when computers can be most helpful.

Games like chess and Go proceed in a rigorous turn-by-turn process, and a very limited number of moves can be made by each piece. There are only six types of chess pieces, and at the end of the game, there is an objectively defined winner. This limited set of moves and narrow definition of winning means that competing computer programs can hone their skills by playing millions of games against each other and studying the results.

Compare this to a typical legal document, such as a contract: Far more than six key terms are at play in most agreements. And the contract represents a business relationship that likely has multiple opportunities for winning and losing, depending on what is happening on a particular day.

When AOL agreed to purchase Time-Warner in a US$165 billion merger, it was seen a transformative deal for both companies. However, by the time the deal closed, the value had dropped by over US$80 billion. In other words, a good deal on one day might end up as a bad deal a week later.

As demonstrated by their ability to play millions of simulated games against each other, computers have certain advantages: They don’t tire, have a great memory, and can explore endless combinations of defined rules. These strengths are more conducive to assisting some lawyer work processes, but not others.

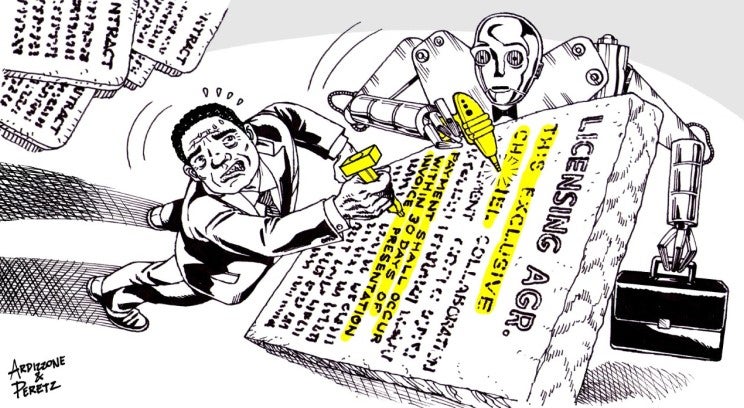

For example, imagine you are helping a corporate client review a potential supplier’s draft agreement. You run a computer program to read the 78-page master services agreement and its six appendices and three exhibits. How can the computer help?

The computer’s infallible memory can be supremely helpful in finding, locating, and remembering specific terms and how they were defined earlier in the agreement. Second, as midnight approaches, you notice the computer is as chipper and alert as ever — which is more than you can say for your colleagues.

Third, in your rush to focus on certain sections, you fail to notice that there are two different sections both labeled as 5(g) — but your computer spots it for you automatically because there are well-defined rules for how numerals and the alphabet should progress. More advanced programs may even be able to predict which types of clauses are included in the draft.

On the other hand, advising your client on an agreement documenting a business relationship requires far more than a good memory, level demeanor, and superb counting skills. A common theme among the aforementioned is that they deal with information contained in the four corners of the agreement itself. What the computer does not understand as well is the ever-important business context — the area where the astute corporate lawyer is best positioned to continue to add value.

The lawyer is the one who figures out questions such as: What are our goals for the relationship? What is my client worried about? How important is this deal? Who has more bargaining power — our side or the counterparty? Do we have a backup plan in place if we cannot get this deal done? How will we judge the success of this deal? The terms proposed in the contract need to be evaluated relative to this broader business context.

To continue to add value as a lawyer, you need to understand the business reasons your clients want to put a contract in place. Ask them what could go awry in the relationship that would require it to be ended or renegotiated. Hop on the relevant ACC discussion board and ask what types of challenges others have had with particular types of business relationships and how to plan ahead for those.

Another area where you need to deploy your unique expert contextual skills is determining where technology can most readily fit into your company’s work process. The biggest obstacle to the successful deployment of technology is often a failure to use it properly. Study your workplace and decide which business behaviors are ingrained in people. Changing an existing behavior can be harder than addressing a new situation, where no prior coping behavior previously existed.

If new software could be helpful but requires you or your colleagues to significantly change your behavior, it will be hard to convince others to adopt the software. By contrast, if you can identify tasks that are being ignored or currently creating a huge pain point, then you are more likely to convince your co-workers to embrace the new technology.

In many instances, you need to explain the prospective change in terms other than dollars or efficiency. One study of organizational behavior suggests that people are more motivated to make changes to help their colleagues, rather than to help the company itself. You are the expert on the motivations and aspirations of your colleagues. You need to use this expertise if you want them to adopt new technologies.