CHEAT SHEET

- Collaboration creation. Fannie Mae and the law firm created a scorecard to assess and account for the value that the law firm delivered to the company. The scorecard would not only track the quality and hours billed, but also take into account “how” the work was completed.

- An open dialogue. Maintaining an open dialogue between the law firm and the Fannie Mae legal department was crucial in ensuring that the vision for the relationship was clear and efficient. Both parties held responsibility for the problems and the solutions regarding the path forward.

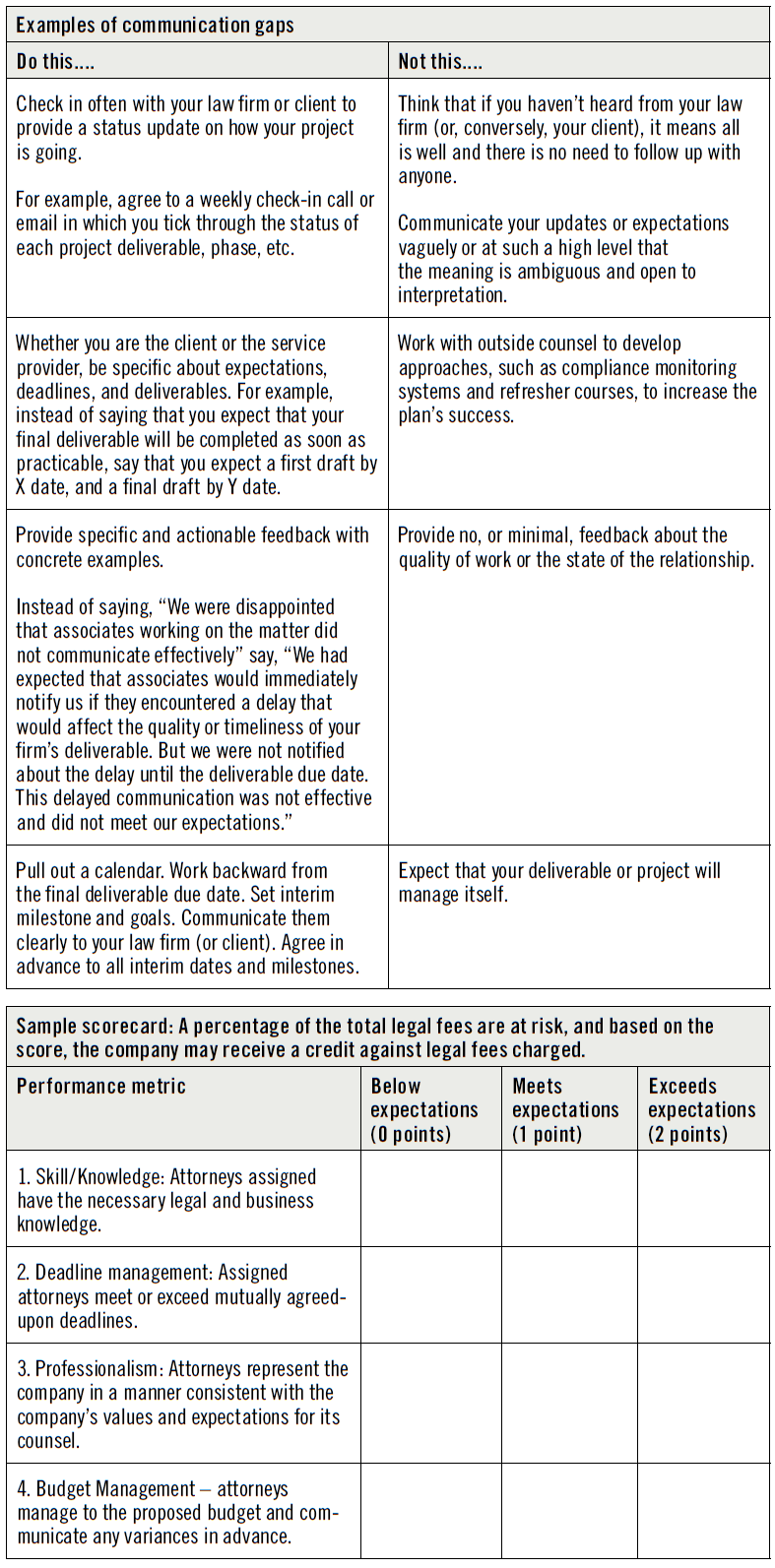

- The scorecard. In establishing the scorecard, the law firm and the Fannie Mae legal department agreed on the types of performance to be measured, set specific metrics that could be measured objectively, and agreed on what proportion of the project fees would be at risk if expectations were not met.

- Road ahead. The scorecard approach has great potential to improve “how” the work is done, and increase the value of the engagement between a law firm and in-house counsel. It helps the law firm understand expectations, and provides clear metrics to follow along the way.

The global head of a large practice group and I sat down for a difficult discussion. Our client/law firm relationship was at a crossroads, and we had a choice between two challenging paths moving forward. One was to end our relationship. It might have been easier, in the short term, for my in-house team to end the relationship and find another firm. However, given the in-depth institutional knowledge the firm had of my company, there would be long-term costs to severing ties. The second choice required a hard and honest conversation that would deliver greater value over the long term for the company.

The communications issues could not be laid solely at the feet of the law firm. We realized that we needed to manage performance more closely so that there would not be surprises and disappointments. I hoped that the law firm would be open to setting these expectations and being evaluated against them.

The challenge

The challenge that this partner and I faced was not legal or regulatory. It was a question of how best to maintain high standards of professionalism in day-to-day service, performance, and communication. I felt these issues went to the core of the relationship that my company, Fannie Mae, had with his law firm. My team felt that level of professionalism and service delivered by the associates at the firm simply did not meet our expectations, and the relationship was suffering as a result. The goal was to preserve the valuable technical and institutional knowledge that this partner and his firm had delivered over the years to Fannie Mae, while improving the firm’s service.

The solution

Fannie Mae and this firm collaborated on a solution: a performance scorecard to assess and account for the value the firm delivered to my company. The scorecard approach we agreed to measures more than just hours billed or the quality of the work product. It goes to the deeper and defining attributes of day-to-day client satisfaction — how work gets done and what behaviors we expect from every individual working on our account.

A common way to assess law firms is to think about hours billed and the quality of the finished work product. What my team had not done before was to clearly articulate the qualities and behaviors we expected in our day-to-day engagement with a law firm (e.g., timeliness, consistency of work product, responsiveness, collaborative work style, etc.).

In this case, the challenges that had brought us to this difficult conversation were not about the quality of the final work product itself. The issue was the “how,” and particularly how much support was required from in-house counsel to ensure the firm’s delivery of that finished work product. As in-house counsel, we measure the performance of our relationships with our internal business clients across many dimensions. Our daily work, and “how” it’s done, is just as important as the final work product. We saw the potential benefit in extending that same performance analysis to our outside counsel, considering a number of questions around “how” the work got done. Did the firm deliver by expected deadlines? Did its attorneys communicate consistently, effectively, and collaboratively with our team? Did they think about the practical and pragmatic dimensions of how their proposed solutions might work?

If the attorneys at a firm do not consistently meet the “how” expectations, then the service experience is diminished. In-house counsel know the internal business client is our customer, and deadlines must be met. Imagine if outside counsel did not manage their client’s expectations around deadlines, and as a result did not deliver a key written deliverable on time. That failure would have a ripple effect on in-house counsel’s ability to deliver to internal clients, and impede the ability of the business to begin, continue, or complete key activities. The client — in this case, us — would be dissatisfied and the value of the firm’s work would be diminished.

The law firm partner and I agreed that we shared a vision of maintaining and increasing value derived from the relationship, which allowed us to talk candidly about the issues we faced. I had confidence in the quality of the firm’s lawyers, but thought that our day-to-day collaboration needed to align much more tightly on “how” to get the work done so that our expectations were consistently met.

Again, the caliber of talent at the firm was not a driver of our concerns. Most of our challenges were rooted in day-to-day engagement and communication between the firm and my team.

When I learned from my team about the day-to-day frustrations resulting from how the firm communicated, it was a surprise. I did not have full visibility into the friction points of the relationship. I wanted to use this opportunity to grow and strengthen the collaboration by establishing clearer expectations regarding the “how.” The communications issues could not be laid solely at the feet of the law firm. We realized that we needed to manage performance more closely so that there would not be surprises and disappointments. I hoped that the law firm would be open to setting these expectations and being evaluated against them.

At Fannie Mae, we work with performance scorecards at divisional and corporate levels. It seemed natural to explore using a scorecard with the law firm. I was looking for a more timely and specific way to measure the ongoing quality of how our groups worked together on a daily basis — for both of our sakes.

When the partner and I sat down to talk, he was very willing to work with me to explore how to make things better. It helped that both of us were familiar with professional service agreements and vendor contracts for other sectors. We were both familiar with service-level agreements, scorecards, and the concept of measuring performance across a variety of metrics — and putting fees at risk if expectations were not met.

Here’s the approach that we took to establish a performance scorecard:

Step 1: Agree on types of performance to be measured. Once we agreed on the concept of using a scorecard, we had to determine what types of expectations warranted inclusion. We had to agree that the expectations went to the fundamentals of the firm’s professional services, and the partner had to be willing to have the firm’s people measured in this way.

Step 2: Set specifics. We established the criteria we would measure objectively. These included: subject-matter skills and knowledge; regular communications, including deadline management; following client instructions; professionalism; demonstrating an understanding of the project’s objective; and budget management.

Step 3: Put fees at risk. This may have been the most important step. We agreed on what proportion of the project fees would be at risk for failure to deliver at expectations for these criteria on the scorecard.

The outcome

A core challenge, especially with two large institutions working together, can be facilitating clear communications, setting shared expectations, and maintaining clarity for staff at all levels of the engagement. We believed that the “how” was now captured by the scorecard elements, and that the scorecard elements identified and addressed the root causes that had initially precipitated the difficult discussion.

Lessons learned

We recommend using the scorecard approach because it has great potential to improve “how” work is done, and increase the value and quality of the engagement between a law firm and in-house counsel. A scorecard introduces transparency on both sides. It helps the law firm because clients’ expectations are clearly stated, documented, and measured. It gives the firm concrete, specific things to focus on at their end — for example, knowledge, skills, and responsiveness — and it helps provide early warning signs when things are going off track. These warning flags are valuable to both client and firm. In-house counsel often rely on law firms for the most important projects, and keeping these matters on track is critically important.

If you are thinking about using a scorecard, I encourage you to do so. Keep these considerations in mind:

- Do your research before you have the “difficult” conversation suggesting the use of a scorecard. This will give you a good sense of the categories of performance you would like to measure. And it will enable you to make a preliminary threshold assessment of whether or not to invest the time in developing a scorecard.

- Organize your thoughts based on your research to determine the thematic issues that can be consistently measured and evaluated on a scorecard.

- Be direct and open. Professional service providers are looking to improve and want to retain their clients. And as a clients, we want to obtain the highest value from the relationship. Beating around the bush won’t help things get better, and could make things get worse — for both the firm and the client.

A scorecard introduces transparency on both sides. It helps the law firm because clients’ expectations are clearly stated, documented, and measured. It gives the firm concrete, specific things to focus on at their end — for example, knowledge, skills, and responsiveness — and it helps provide early warning signs when things are going off track.