CHEAT SHEET

- Risk aversion. Most law firm cultures are built around a strong bias to risk aversion. However, in transitioning to a more entrepreneurial role, lawyers must expand their perception from “no” to “yes,” even if the next question is “how?”

- Wearing two hats. For lawyers in business roles, it can sometimes be difficult to look beyond the legal issues when making decisions. As such, it’s essential to develop the ability to wear two hats at a time: one for the business, and one for the legal department.

- A fresh perspective. As in-house counsel, your seat is often at the center of the table. Given your understanding of the business from all angles, your input will be fresh and unique.

- Instilling interest. Unfortunately, not everyone is cut out to be an entrepreneur. Above being able to understand the business, lawyers must have a legitimate interest in business operations to succeed.

April 2017 marked the 15-year anniversary of my law school graduation. I went through several stages before I realized my legal ambitions, ranging from public service to a coveted spot at a national firm. However, in 2008, I made the jump to general counsel for a technology company. Today, I’m still a GC with the same company, as well as a shareholder. Given my time with the company, familiarity with our “product,” and background, I am often called upon for business-related decisions. Having found a seat at the table, I have realized that despite a lawyer’s training, it is not quite as common as some would think for general counsel to move into a business role.

On the surface, it might appear normal for lawyers to rise into CEO roles. However, in most companies, from multinationals to technology startups, a general counsel is the trusted, go-to advisor that heads of departments and shareholders can confide in. Entering into a company as general counsel, one quickly realizes that the skills acquired in law school and throughout a legal career can (if used correctly) be extremely useful in moving into a CEO — or entrepreneurial — role.

However, looking at it more closely, it seems that lawyers develop certain qualities that can actually prove to be an obstacle in the business world. This article explores the reasons for why the transition from lawyer to entrepreneur/CEO is somewhat uncommon, and highlights the input of former lawyers who have become successful entrepreneurs.

Lawyers are often afforded the ability to be at the heart of important matters in a relatively short period of time, and receive a broad understanding in a variety of areas, including technology, banking, real estate, and venture capital. Early on, they are exposed to the inner workings of large deals, and, with time, work with the upper management at major companies. Furthermore, many skills, like the ability to cope in high-pressure situations or negotiating and analyzing large amounts of information, are cultivated.

For those who make the transition to an in-house position, they can find themselves in a unique and privileged role within a company, which gives them an understanding of both operations and management. They will also attain an unmatched level of trust among all sectors of the organization. This allows the chance to foresee both managerial and operational issues that may arise from certain decisions. Collectively, this is the perfect “training ground” to enter specific verticals and succeed.

In reality, a law degree has been undervalued in the business world, and companies are reluctant to see their general counsel in the same light as business executives. Typically, lawyers begin their careers in an environment where risk is frowned upon and decisions are only made after thorough analysis and paperwork. Entering a company, general counsel are often regarded as “deal breakers,” due to the tendency to be cautious and risk averse — which can sometimes throw cold water on deals. The perception is that, due to their obsession with details, lawyers can’t see the big picture. I have often witnessed entrepreneurs claim lawyers lack the bold vision, marketing skills, and financial savvy necessary to lead a company.

While general counsel can take steps to be seen as less of the “no” person and compromise without losing focus on the legal issues, the reality is that some entrepreneurs have preconceived notions about lawyers which are often difficult to overcome. To do so, the lawyer should seek more of an entrepreneurial role to demonstrate the dual nature of their abilities and how they can be an asset in an operational capacity.

To gain a better perspective on this issue, I reached out to three very different, yet equally successful entrepreneurs, all of whom began their careers as lawyers or during law school: Chris Sacca, Mitch Garber, and Anna Santeramo.

I asked each subject three questions related to habits developed in law school or as a lawyer that have contributed to their success as an entrepreneur. What skills did they need to develop or drop? Do they have advice for lawyers aspiring to entrepreneurial roles? Each one had a unique trajectory from law to business, and a different approach to getting there.

The entrepreneurs

CHRIS SACCA

Chris Sacca founded Lowercase Capital, a successful venture capital fund in Silicon Valley, CA. He has also appeared as a guest on a few episodes of ABC’s Shark Tank. He attended Georgetown University Law School, and from there joined Fenwick & West in Silicon Valley — only to be let go with his entire graduating class four days before 9/11.

Sacca eventually landed at Speedera Networks and later joined Google. Although officially hired as corporate counsel, who reported to General Counsel David Drummond, Sacca got hired as they were looking for a lawyer with knowledge in the data space to negotiate and purchase data centers across the country.

After leaving Google in 2007, Sacca founded Lowercase Capital and through a series of early investments in Twitter, Uber, and Instagram, managed to create what is often regarded as one of the most successful funds in Silicon Valley.

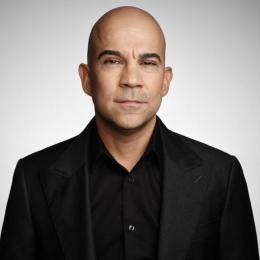

MITCH GARBER

Mitch Garber graduated from the University of Ottawa with a civil law degree, and began specializing in gambling law for a boutique firm. He later left the profession to join SureFire Commerce Inc., a NASDAQ-listed payment-processing company whose clients included all of the major licensed online gambling sites around the globe. After corporate reorganizations, he became CEO of the newly formed Optimal Payments Inc. In 2006, he moved to the pinnacle of the industry when he was appointed to be head of online gaming company PartyGaming PLC.

Since 2009, Garber has been CEO of Caesars Acquisition Company, head of Caesars Interactive Entertainment, and chairman of Cirque du Soleil since 2016.

ANNA SANTERAMO

Anna Santeramo is co-founder of StyleBee.com, an app that allows professional women and men to book on-demand, in-home beauty services like haircuts and blowouts through their smartphones. Santeramo spent many years in both New York and Los Angeles working for large multinational firms including Fried Frank and Skadden Arps.

Chris Sacca

What are the main qualities or habits you developed either in law school or as a lawyer that have contributed to your success as an entrepreneur?

“I have always tried to examine a situation with fresh eyes. No matter how new the project, we all bring to it so many built-in assumptions as we tackle any project. One of the hardest things to do is unshackle one’s self from the myopia that results and leave your vision open to new solutions. New, creative, unconventional approaches to things are not particularly relished in law firms. For example, as a first-year lawyer, I came up with a new way to issue stock to employees that avoided variable accounting treatment. At first, I was told to know my place. Within a month, our biggest client was using my approach.”

Sacca touches upon an important matter that can creates an intellectual obstacle for lawyers early on. A lawyer’s first exposure is often within the confines of a law firm based on an antiquated associate-partner model — which has changed very little over the years. Associates are not hired for their creative or intellectual curiosity, but are expected to grind out many billable hours for the first five to 10 years. Thinking outside the box, finding new solutions, or disrupting models is considered unacceptable. Over time, we develop a sense of thinking within the confines of a matter. As an entrepreneur, this will almost guarantee a quick death when running a business.

“I always go to the primary source documents. Back at the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown [University], I had a professor who required us to interview the actual principal actors for the papers we were writing, as well as to get our hands on the actual documents we were citing. I have continued this habit ever since. While I deeply appreciate the counsel I get from my lawyers, whether it’s looking at the law, understanding a new market, or trying to get my head around a novel technology, I skip the abstracts of others and go directly to the source.”

The transition from lawyer to CEO/entrepreneur is not common: Lawyers in organizations are sometimes viewed as risk averse, seen as the “no” person or “deal breaker.” In order to succeed in operations or as an entrepreneur, what skills do you believe lawyers: (1) need to develop; and (2) what skills or habits do they need to drop (if any)?

“There is a huge difference between risk aversion and risk analysis. Most law firm cultures are built around a strong bias to risk aversion. Essentially highlighting each risk and decrying each as a block to feasibility. As an entrepreneur, we encounter risk at every turn. Yet, the distinction is that we must weigh the relative likelihood of a bad outcome and the cost of the eventuality and use that analysis to make a decision. It’s about seeing everything through a lens tinted ‘no’ and transitioning to a worldview that starts with ‘yes,’ even if the next question is, ‘how?’”

Having followed Sacca’s career for some time, his responses, much like his business philosophies, are not atypical of the advice that you would find in business textbooks, or from the usual lawyer-turned-CEO. In my experience, the transition from no to yes should be the primary focus of lawyers who want to get away from the purely legal mindset in operations.

I have seen this when dealing with external counsel. They will be fixated on details that are part of an internal checklist they follow almost religiously, which can create an obstacle in moving the deal forward. Oftentimes, as liaison between external counsel and our CEO, I will remind them that while I appreciate their advice on specific matters — be it regulatory or compliance — we need to find a solution rather than highlight a problem.

Another major obstacle Sacca points out, and I believe lawyers need to overcome, is risk. From our first torts class, we are trained to see the worst-case scenario in situations that can be a positive and negative. From a CEO point of view, when used wisely, this can save a company from potential issues. From a founder’s point of view, such as Sacca’s, this can be crippling.

Mitch Garber

What are the main qualities or habits you developed either in law school or as an lawyer that have contributed to your success as an entrepreneur?

“In short — reading, analyzing, and being opinionated.”

The transition from lawyer to CEO/entrepreneur is not common: Lawyers in organizations are sometimes viewed as risk averse, seen as the “no” person or “deal breaker.” In order to succeed in operations or as an entrepreneur, what skills do you believe lawyers: (1) need to develop; and (2) what skills or habits do they need to drop (if any)?

“Lawyers in law firms have the most difficult time transitioning. Usually, it will only happen if a client recruits them to leave the firm. In-house lawyers, on the other hand, can take two paths: being the pure in-house counsel (usually known as the person who says ‘no’ to everything), or being the pragmatic lawyer who takes an interest in the actual business and the people running it and is seen to look for solutions while protecting the company. Having the respect of peers, as someone who truly understands the business and its competitors, is key.”

In your case, taking into account your career trajectory: What do you think was the greatest factor that allowed you to succeed, and what advice would you give lawyers who aspire to the CEO role?

“I think having a genuine interest in the business operations, the competitive landscape, and making that knowledge known and valued is key. It’s not for everyone, however. I would always be reading analyst reports and other materials with a business hat and not a lawyer hat. Thereafter, I developed the ability to wear two hats at a time.”

Finally, why do you think we don’t see more lawyers becoming CEOs or as entrepreneurs in general (as opposed to engineers, etc.)?

“Lawyers take the safe route: law school, articling, comfortable salary moving from associate to partner: all low risk. Entrepreneurs are the opposite.”

This touches on an earlier point Sacca made in relation to the culture of law firms. This safe, low risk route is something lawyers are reluctant to deviate from and translates into taking risks in operational roles.

Garber’s practical, hands-on experience from a private practice laywer to CEO of one of the largest gaming websites in the world offers a lesson. Namely, being the “pragmatic lawyer” and “having the respect of peers as someone who truly understands the business and its competitors is key.” Moreover, his assessment that the trajectory is not for everyone is something I have seen time and time again. I’ve witnessed too many lawyers who move in-house who are unable to look beyond the legal issues, and are consequently less likely to be involved in decision-making.

Anna Santeramo

What are the main qualities or habits you developed either in law school or as a lawyer that have contributed to your success as an entrepreneur?

“Discipline, persistence, and analytical rigor when looking at issues.”

Lawyers in organizations are sometimes viewed as risk averse, seen as the “no” person or “deal breaker.” In order to succeed in operations, an entrepreneur or CEO, what skills do you believe lawyers: (1) need to develop; and (2) what skills or habits do they need to shed (if any)?

“Corporate lawyers should work in a business capacity at a company because an entrepreneur’s mindset is completely different from a lawyer’s mindset. Lawyers want to minimize risks regardless of the business implications of their decisions, whereas entrepreneurs want to get things done and move on. Therefore, even if a decision is sometimes questionable from a legal standpoint, it might make sense if that decision helps a business take it to the next step.”

There are no skills or habits that lawyers develop that are inherently bad for business. What is bad for business is the general pessimistic predisposition that lawyers can possess. I’m not sure one can change her or his predisposition, which could be one reason for holding lawyers back who want to start their own business. On the other hand, lawyers often make great CEOs at big companies — as a CEO is essentially a manager, and lawyers are great managers.

What advice do you give lawyers who aspire to get into business or become an entrepreneur?

“I would advise them to first transition to work for a company in a business development or operational role and go from there. No need to jump right in without any background! There is an obsession, especially in Silicon Valley, that everyone has to be an entrepreneur to be cool, but the truth is that it is not for anyone. While it might cool for some people, it might actually be a miserable experience for others, especially if they are averse and generally conservative.”

Santeramo’s final point is critically important: Not everyone is cut out to be either an entrepreneur or transition into operations. Over and above being able to speak the same language, there must be a legitimate interest in business operations and an understanding that there is more to the company than its legal issues.

As someone who has been involved more and more on the business side of operations, whether it’s M&A, post-closing integration, or high-level management decisions, there are habits that lawyers need to shed, and others they need to adopt in order to flourish. For one, understanding income statements, balance sheets, and business valuations is something lawyers often do not touch during their education or career. I would highly recommend ACC’s Mini MBA at Boston University, which I completed in 2012. The three-day course gave me excellent insight and, more importantly, a valuable understanding of accounting, finance, strategy, and other business disciplines.

I followed this with a period of binge-reading business related books, like Good to Great by Jim Collins, Dream Big: The 3G Way to the Magic of Thinking Big by David Schwartz, and How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie. This was extremely useful and opened my mind to a different way of thinking.

Lastly, I made a point to join meetings that may have not necessarily required my presence — be it the weekly scrum with the development team or our video content team’s strategy meeting. This is something I would strongly recommend for all in-house counsel to better understand the product of the business, but even more so for those with an acute interest in the business/operational side.

Conclusion

Many great legal careers begin, transition into (as well as out of), and end in-house. As the lawyers profiled in this article demonstrate, everyone’s path is different. A common thread, however, is that the path to leadership is paved with those who are able to look beyond the risks and visualize the opportunities around every corner. Whether your individual career plans include moving from the law department to the C-suite, or from one office space to another — a thorough understanding of the business (whatever it might be) combined with an entrepreneurial spirit can only help your career grow.

Tools for lawyers seeking to make the transition into a management role

It’s about seeing everything through a lens tinted “no” and transitioning to a worldview that starts with “yes,” even if the next question is, “how?”

I have witnessed both general counsel and outside counsel debating endlessly with a CEO over a decision, which they labeled impossible — without attempting to find a solution or compromise. This serves no purpose except to guarantee that the legal department will be less involved the next time around and with greater reluctance.

“Having the respect of peers as someone who truly understands the business and its competitors is key.”

Understand the business from A to Z. This begins with joining meetings, which you may not be involved with directly, in order to ask questions. It also involves looking at the matter from your colleague’s point of view, be it through approving and reviewing agreements, or structuring a deal. Understanding the business and what is important will allow for better decisions to be made for the greater good — without compromising legal obligations.

“First, transition to work for a company in a business development or operational role and go from there.”

The education, early years, and continual efforts to be a valuable attorney require a tremendous amount of energy and sacrifice. Depending on the company size and industry, moving into an operations role may mean that you will be replaced as general counsel. Before embarking on a new career, spend some time in operations. Attend meetings, listen in on calls, etc. This way, you can be absolutely sure that the move is both a good fit and something you can see yourself doing for the long run.

Use your existing tools.

Lawyers do not lack the qualities or assets that can prove useful for a company, including the ability to read and analyze large amounts of content, filter out trivial matters, and develop a strong work ethic, which is often instilled early on. Other skills like email etiquette (including response time and organization) are often revered in companies.

Make the most of your opportunities.

Sometimes, your seat is at the center of the table — next to the CEO, board members, heads of departments, and the most important clients or partners of the company. If your ambition is to move on from a purely legal role, this is the greatest opportunity to show your skills. Given your understanding of the business from all angles, your input will likely be fresh and unique. Give it.