CHEAT SHEET

- The first step. The first step in an OSHA inspection is the unannounced arrival of an OSHA compliance officer to the employer’s worksite. Afterward, there will be an opening conference where the compliance officer will inform the employer of the scope of the inspection and what is specifically reported.

- OSHA 300. Keeping accurate OSHA 300 logs and OSHA 300A summaries is important because they will be requested early on in the inspection process. Depending on department size, these logs could also be requested on an annual basis.

- Impending citation. Under the federal scheme, an employer has 15 business days to determine whether to contest the citation, the penalty, the abatement deadline, or a combination. When OSHA issues a citation, the employer is entitled to attempt to resolve the citation before the end of the contestation period through an informal conference.

- The litigation game. Jurisdictions are split on the admissibility or use of OSHA citations in a civil action. Therefore, it is important to understand how your jurisdiction addresses admissibility.

The US Congress enacted the Occupational Safety and Health Act (the Act) in 1970 to reduce workplace injuries and illnesses and to hold employers accountable for providing a safe and healthy work environment. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is the federal agency charged with promulgating and enforcing safety and health rules in the workplace. While the intent of the Act was to improve the circumstances of the American worker, a byproduct has been the attempted use of OSHA standards against employers to establish a standard of care owed by defendants in work-related tort cases. Organizations friendly to organized labor have also been using workplace injury recording forms required by OSHA, known as OSHA 300 forms, against employers to stir media and employee interest in union organization efforts. While courts have differed considerably on the admissibility of OSHA standards in personal injury cases to establish the standard of care, the best approach to avoiding work-related litigation is prevention. In-house counsel who represent clients in the OSHA-regulated industries should have a basic understanding of OSHA, its investigation and litigation processes, and proper injury recording and reporting criteria to assist their clients and decrease the chances of being issued citations and penalties. In the event that OSHA hands down citations and penalties, early understanding and strategic decisions can lessen the impact and likelihood of admissibility of the citations as evidence in related litigation.

OSHA requires employers to record work-related injuries and illnesses on specific forms often referred to as “logs.” Employers with 10 or fewer employees and in certain low-hazard industries (finance, insurance) are exempt from recordkeeping and reporting requirements.

This article will provide in-house legal counsel with information on OSHA compliance, injury recording and reporting criteria, how to handle an inspection, citation, and penalty, the contestation and appeal process, whistleblower complaints, and tips and strategies the civil litigator can employ in underlying civil litigation where the OSHA standards are at issue.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration

OSHA’s purpose is to “assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the states in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health; and for other purposes.” Unlike some agencies, OSHA has the authority to inspect workplaces, to promulgate and enforce safety and health standards, and to issue citations and penalties for violations of the standards. OSHA is not reticent about using its enforcement powers as well as the power of the press to “blame and shame” employers into compliance with safety and health standards. Other sections of the Act establish the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission (Commission), an independent tribunal that hears disputes between employers and OSHA. OSHA also investigates allegations of retaliation by employers against employees under several statutes and for the last couple of years has increased focus and resources on ensuring that employees can voice safety and health concerns and complaints without fear of retaliation.

The Act permits states to opt to run their own occupational safety and health programs instead of the federal OSHA so long as state plans are at least as stringent as the federal plan. Twenty-five states have made this choice, and many states have adopted standards that are far more stringent than the federal plan. State plans can vary in significant ways from federal plans, so be sure to make this determination from the beginning.

The Act defines an “occupational safety and health standard” as a “standard which requires conditions, or the adoption or use of one or more practices, means, methods, operations, or processes, reasonably necessary or appropriate to provide safe or healthful employment and places of employment.” A standard may address a category of equipment (cranes), a class of harmful agents (carcinogens), a kind of work (hazardous waste cleanup), an industry (construction), or an environmental area (confined space). Standards are grouped into four major categories: general industry, construction, maritime, and agriculture.

Another component of the Act addresses injury and illness recording and reporting. OSHA requires employers to record work-related injuries and illnesses on specific forms often referred to as “logs.” Employers with 10 or fewer employees and in certain low-hazard industries (finance, insurance) are exempt from recordkeeping and reporting requirements. Federal OSHA provides that all work-related fatalities must be reported within eight hours and all in-patient hospitalizations of one or more employees, amputations, and any eye loss must be reported within 24 hours of the incident. State-run plans (i.e., California and Utah) have different reporting time periods, which may be considerably shorter than the federal OSHA reporting requirements.

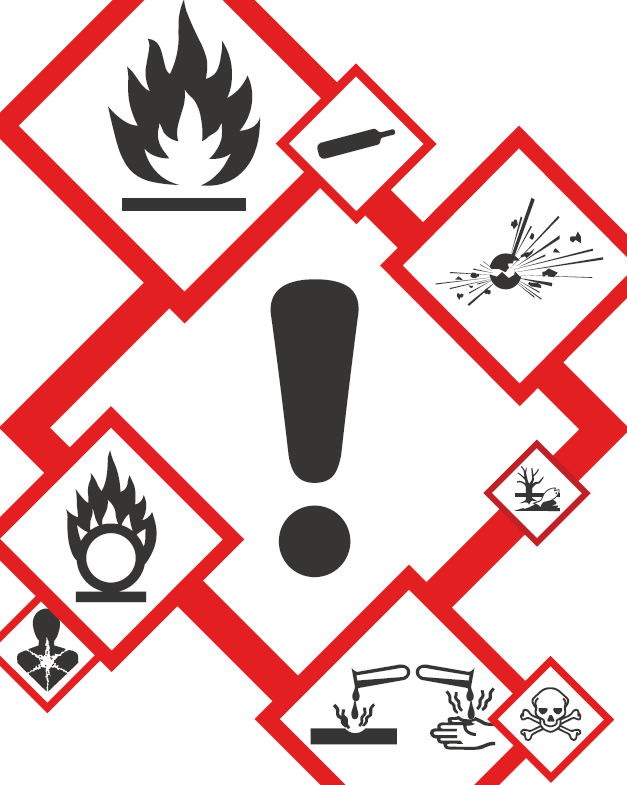

Categories of Violations

| DE MINIMIS | Technical violation of OSHA rules that have no direct impact on health or safety |

| OTHER THAN SERIOUS | Violation would likely not cause death or series harm but has a direct and immediate relationship to the safety and health of employees |

| SERIOUS | There is a substantial probability that death or series physical harm could result from the hazardous condition |

| WILLFUL | The employer consciously, intentionally, deliberately, and voluntarily disregards safety standards |

| REPEAT | After an initial citation, if a subsequent investigation reveals another identical, or very similar violation, the employer may be cited for a repeat violation |

| FAILURE TO ABATE OR CORRECT THE HAZARD | When an employer receives a violation citation, and the employer fails to correct the violation by the specified date |

I. OSHA inspection process

There are several reasons OSHA may

initiate an inquiry or inspection.

- Imminent danger: These scenarios are of the highest priority and occur when OSHA learns of a hazard that could potentially cause death or serious bodily harm.

- Fatalities, catastrophes, and serious injuries: These inspections are initiated following an employer report of a work-related fatality or in-patient hospitalization.

- Complaints: These inspections are initiated as a result of an employee/union’s contacting the agency to raise a health and safety concern.

- Referrals: Safety and health concerns are reported from other agencies or individuals outside the company.

- Programmed inspections: These inspections target specific high-hazard industries or workplaces.

The first step in the OSHA inspection is the unannounced arrival of an OSHA compliance officer at the employer’s worksite. The employer should always verify the compliance officer’s credentials. The inspection can take place based on the employer’s consent or pursuant to a warrant if consent cannot be obtained. Legal counsel should be in a position to advise the client whether to cooperate and consent to an inspection or to demand a warrant. Factors to consider are the potential for creating a poor working relationship with the agency, loss of control over the inspection, costs to challenge the warrant, maintaining credibility, and publicity. Note that a warrant is not required if OSHA observes a violation that is in “plain view.”

The second step in the OSHA inspection process is the opening conference. During the opening conference, the compliance officer will inform the employer of the scope of the inspection and what specifically was reported. After the opening conference, the compliance officer will want to conduct a “walk around,” a visual inspection of the area of concern. The employer representative should take detailed notes, stay near the compliance officer, and take identical photos of anything the compliance officer photographs. It is crucial that the employer understands precisely why OSHA is there and what inspection activities the compliance officer intends to conduct. Once this is known, the employer should do the following:

- Do a sweep of the path to and including the incident area to ensure no “plain view” violations exist.

- Determine what employees may be interviewed.

- Determine what management employee will attend the walk around so it is properly managed.

- Gather OSHA 300 and 300A logs for the prior three years for the facility.

- Gather written training materials and sign-in logs for the equipment, hazard, or area that is the focus of the complaint.

- Make certain the management employee participating in the inspection has a camera/video camera to document what OSHA documents during the walk around.

The Act permits compliance officers to question any employee privately during regular working hours. It is important to tell employees that it is their right to decide whether, where, and when to talk to OSHA, not OSHA’s right. Employers should work with OSHA to schedule employee interviews so it doesn’t interrupt ongoing business activities, and so the employer can inform employees of their rights and explain the interview process to them. Further, the employer’s legal representative may be present during interviews of management because the statements can bind the company. In contrast, OSHA, in most cases, will refuse to allow the employer’s legal representative to be present for non-management interviews. Nonetheless, always ask to be present during non-management interviews because exceptions are sometimes made. Non-management employees should also be informed of their rights in an OSHA interview, including the right to have a chosen representative present. Unionized employees are entitled to have a union representative attend the interview.

Following the interviews, the compliance officer will request documents. As a best practice, employers should ask the compliance officer to submit a written document request to ensure that all requests are relevant, reasonable, and subsequently tracked and answered. It is also important to request a written document request so that the employer may determine whether to voluntarily provide non-mandatory records or to require a subpoena. Certain injury records, such as OSHA 300 logs, are required to be produced within four business hours of the time of the request. Documents should be reviewed before production to ensure responses are responsive and on-point and for confidentiality and trade secret protection. Materials not designated as trade secrets or confidential information may be available to company competitors, opposing counsel, and other adversaries through Freedom of Information Act requests. Therefore, it is important to label all items containing trade secrets or confidential information. Employers should designate a single point of contact for communications and any further requests.

A closing conference is the final step in the OSHA investigation process. During the closing conference, the compliance officer will explain his or her findings and outline likely citations, including their classification. The closing conference is typically held weeks, if not months, after the inspection is initiated and is often over the telephone. It is important to remain calm during the closing conference; however, targeted and specific questions regarding what evidence or observations the compliance officer is using can provide helpful information if the citation is contested.

II. OSHA 300 logs and OSHA 300A summaries

Keeping accurate OSHA 300 logs and OSHA 300A summaries is important for several reasons: (1) The forms must be produced within four business hours after demand by the compliance officer; (2) OSHA 300 logs and 300A summaries must be provided to any employee or designated representative requesting them by the end of the next business day; (3) federal OSHA now requires that employers with 250 or more employees electronically submit their OSHA 300, 300A, and 301 information by July 1, 2018, for 2018 data, and on March 2 of each year, beginning in 2019, where the forms can be viewed by opposing counsel, unions, and employees; and (4) the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes a list each year of the average injury and illness data for industries grouped by North American Industry Classification System codes, against which your company may be compared. Because of the availability of injury data to employees, media outlets, opposing counsel, and union organizers, plus the introduction of OSHA’s electronic reporting submission requirements, it is more important now than ever, that on-the-job injuries and illnesses, and resulting time away from work, be tracked accurately. There has been a recent trend of media outlets and pro-union employee interest groups analyzing injury data, calling discrepancies into question, and publishing aggressive news stories with their findings.

Employers who are not exempt from OSHA’s recordkeeping requirements must record each work-related injury and illness that results in death, “significant injury or illness diagnosed by a physician,” days away from work, restricted work or transfer to another job, medical treatment beyond first aid, or loss of consciousness. Employee names are listed on OSHA 300 forms together with a description of the injury. Unless the injury is a “privacy case,” (e.g., a needle prick that results in HIV exposure), names of injured employees cannot be redacted from OSHA 300 forms, which provides ample opportunity for interest groups and opposing counsel interested in discovering injuries to locate current and former employees through which to cross-reference injury information.

III. Citations and penalties

Despite an employer’s best efforts, there is always the risk of receiving a citation and accompanying penalty. Under the federal scheme, an employer has 15 business days to determine whether to contest the citation, the penalty, the abatement deadline, or a combination of the same. State plans may alter the contest deadline so be sure to determine the applicable deadline.

When OSHA issues a citation, the employer is entitled to attempt to resolve the citation before the end of the contestation period through an informal settlement conference. This is the first opportunity an employer has to resolve the citation(s) absent litigation and is always a great opportunity to conduct a bit of discovery to determine what evidence OSHA is relying on to support the citations. Compromises include dismissing citation(s), reducing the citation classification and/or penalty, and grouping citations. If a resolution is not reached, then the employer can file a Notice of Contest which initiates formal legal proceedings.

IV. Litigation

The Commission was established by Section 12 of the Act and is a federal agency that adjudicates workplace safety and health disputes. There are two levels of review: the administrative hearing level presided over by a federal administrative law judge (ALJ) and the discretionary appellate review of the ALJ’s decisions by presidentially appointed commissioners via de novo review. Commission decisions are further reviewable in the federal court of appeals.

At the initial step and after the employer files a notice of contest, the case file gets transferred to the Office of the Solicitor within the Department of Labor. The Solicitor files a complaint with the Commission, and the employer files an answer in response. Several affirmative defenses are available to an employer: (1) The “invalid standard” defense argues that the standard is too vague to hold the employer responsible for failing to take notice of the same or that the standard was not adopted through the requisite rulemaking procedures; (2) the “unpreventable employee misconduct defense;” (3) the “impossibility/infeasibility” defense; and (4) the “greater hazard” defense (compliance would create a greater hazard than current operations). From here the case follows the similar path of civil litigation, beginning with discovery. After a hearing before an ALJ, the ALJ will issue a written decision that becomes final in 30 days unless discretionary review is requested through the Commission. If the secretary or the employer disagrees with the Commission’s decision, either party can file an appeal within 60 days of the Commission’s decision in any US court of appeals for the circuit in which the violation is alleged to have occurred or where the employer has its principal office or in the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

V. Whistleblower protections

Under the Act, an employee’s right to raise health and safety concerns is well protected from being discriminated against. The number of whistleblower complaints filed by workers under Section 11(c) of the Act has increased, as have the 21 other whistleblower provisions enforced by OSHA (e.g., Clean Air Act, Toxic Substances Control Act, Federal Railroad Safety Act). A complaint under Section 11(c) must be filed within 30 days of the alleged retaliatory conduct, which begin running from when the individual is notified of the adverse action, not when they actually take effect.

Once the complainant files, OSHA will forward the same to the employer along with a request that the employer respond and provide documentation in support of its actions. An investigator will then commence, typically beginning with witness interviews. If the OSHA investigator determines that retaliation occurred, the case is forwarded to the Solicitor’s Office at the Department of Labor. The Solicitor’s Office reviews the file and must also conclude that retaliation occurred in order to bring a case on behalf of the employee. Under Section 11(c) a complainant does not have a private right of action. If OSHA determines that retaliation did not occur, it will dismiss the complaint; the employee’s sole recourse is to request an internal review with the OSHA regional office and then later with the OSHA national office. The internal review will determine whether the investigation considered all the factual issues and made an appropriate determination.

How an employer responds to a Section 11(c) is critical. An employer should thoughtfully explain the basis for its alleged adverse action against the employee that is consistent with the evidence it presents. Further, an employer should provide documentation that supports its decision such as internal policies and procedures, witness statements, and the employee disciplinary file. Finally, identifying similarly situated employees who raised similar safety complaints and were not disciplined can show that the company had no motivation for retaliating against the complainant.

Prevention is the best way to avoid whistleblower complaints. Employers should train managers in identifying protected activities and to use human resources and legal counsel’s help when action must be taken against an employee. Employers should also respond to all internal complaints by thoroughly investigating them and communicating how the matter will be resolved. Developing a clear record as to why the adverse employment action was taken is essential. OSHA also has developed a best practices guideline for employers that consists of six key elements of an effective anti-retaliation program: (1) leadership commitment, (2) a “speak up” organizational culture, (3) an independent and protected resolution system, (4) training on retaliation, (5) employer monitoring and measuring the “speak up” culture, and (6) an independent audit to assess whether an employer’s program is working.

VI. Tips and strategies for civil litigation

OSHA citations can have a significant impact on collateral litigation, parallel regulatory inspections, and contract indemnification provisions. For example, assume a host company hires a soldering company, and the contract has an indemnification clause. The host company writes an inappropriate hot work permit to authorize the soldering. A fire occurs, and the solder employee and one host employee are fatally injured.

OSHA conducts an investigation and concludes that the hot work permit is inadequate and issues a citation against the host company. The solder employee’s estate then brings a wrongful death suit against the host company and a workers’ compensation claim for death benefits against the solder company. The estate will argue that OSHA standards on hot work set forth the standard of care and that the citation proves a violation of the standard of care. Further, the estate’s counsel will argue that the OSHA citation is the only independent and neutral piece of evidence and conclusively establishes negligence. Assuming that the indemnification clause required the host employer to indemnify the soldering company, the soldering company will now seek subrogation from the host employer; since the host employer received a citation, this too establishes that the host employer was negligent. It is common to see these arguments in construction accident cases. If a violation of a standard resulted in a worker injury, it may be fairly easy to show that the employer failed to meet its duty to keep the employee safe. This is especially true when there is a failure to train.

Jurisdictions are split between the admissibility or use of OSHA citations in a civil action. Therefore, it is important to understand how your jurisdiction addresses admissibility. Some courts say that if the premises owner had control, a duty is owed to the injured worker. Other jurisdictions hold that OSHA does not create a private right of action, and a violation of an OSHA regulation can never be equated with negligence per se because it is an expansion of common law duties. However, some jurisdictions state that an OSHA standard is at best the equivalent of a safety statute, a violation of which produces some evidence of negligence. Some courts have ruled that prior to admitting an OSHA violation as evidence of negligence, the court must find that the owner owed the worker a duty under state law; if no duty is owed under state law, an OSHA violation cannot be used as evidence of negligence.

One of the more solid arguments from the employer standpoint is that the OSHA citations are irrelevant because the only question that will go to the jury is whether the defendant’s conduct was a significant or substantial factor in causing the plaintiff’s injuries. Start with the jury charge in your jurisdiction on the proximate cause or concurring cause. Assert this argument in objections to written discovery and depositions, and, if necessary, seek protective orders to limit discovery of the employer’s alleged violations by arguing that the OSHA violation was not a substantial or contributing factor. Start framing and drafting motions in limine early. Prepare your expert witness and lay witness deposition outlines with this in mind. Finally, argue that the citations were issued by a non-party and by completely different legal standards from those in a civil case. Even if unsuccessful, you will be educating the judge about your case and may possibly get the court to reconsider earlier unfavorable rulings at trial.

Another approach is to argue that the OSHA citations and fine were negotiated. Therefore, the settlement is a compromise between a company that denied liability and an agency that never proved liability, making it inadmissible.

Focusing on the plaintiff’s comparative negligence can be fruitful and in some jurisdictions is a complete bar to recovery. Having a plaintiff admit that they received safety and health training, knew their responsibilities, attended the tailboard (or their employer failed to conduct one) and yet disregarded their own responsibilities of keeping themselves safe can be compelling evidence in front a jury. In other words, demonstrate what the defendant did right and get codefendants to agree that the plaintiff’s own conduct was a root cause of their injuries.

Nonetheless, an employer can use OSHA citations offensively too. Because employers typically have workers’ compensation immunity and cannot be brought into the lawsuit as a party, it provides other defendants a great avenue to designate the immune employer as a non-party at fault and have the immune employer listed on the verdict form for fault apportionment.

As a defendant, you point your finger at the empty chair to defend your client’s own conduct and blame the employer for failing to train or supervise the employee properly. A citation issued by a federal agency ultimately responsible for workplace safety can be damning evidence of employer negligence.

Having an understanding of how OSHA investigations, citations, and standards can affect your client’s case helps you in creating an early case strategy and success in the long run. This is an area of law that often welcomes creativity and an opportunity to educate the court.

Further Reading

29 U.S.C. § 652 (1970).

29 U.S.C. §§ 650-652.

29 U.S.C. § 657.

US Dep’t of Labor, The Whistleblower Protection Programs, OSHA.

29 C.F.R. § 1952; US Dep’t of Labor, State Plans, OSHA.

29 C.F.R. § 1910.02(f).

US Dep’t of Labor, Worker’s Rights, OSHA (2016).

29 U.S.C. §§ 1904.4(a), 1904.41.

29 C.F.R. §§ 1904.1-1904.2.

29 C.F.R. § 1904.39.

29 C.F.R. § 1952.4

29 C.F.R. § 657.

29 C.F.R. § 1904.40.

The procedure for labeling documents as containing trade secrets and business confidential information is outlined at 29 C.F.R. §1903.9.

29 C.F.R. §1904.40(a).

29 C.F.R. §1904.35.

29 C.F.R. §1904.41.

Injury and Illness Data maintained by the BLS is found here: www.bls.gov/iif/oshsum.htm.

29 C.F.R. §1904.7.

OSHA’s interpretive guidance on employee access requirements.

29 U.S.C. §§ 658, 659(c).

29 U.S.C. §§ 660, 661.

29 U.S.C. § 663.

29 U.S.C. § 660(11)(c).

See Teal v. E.I. DuPont Nemours & Co., 728 F.2d 799, 804 (6th Cir. 1984); IBP, Inc. v. Herman, 144 F.3d 861, 865-66 (D.C. Cir. 1998).

See, e.g., Maddox v. Ford Motor Co., No. 94-4153, 1996 WL 272385, at 3-4 (6th Cir. May 21, 1996); Barrera v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 653 F.2d 915, 920 (5th Cir. Unit A Aug. 1981); Cota v. Chiplin Enters., Inc., No. 1:04CV297, 2006 WL 2475770, at *3 (D. Vt. Aug. 25, 2006).

See e.g., Elliott v. S.D. Warren Co., 134 F.3d, 1, 5 (1st Cir. 1998); Rabon v. Automatic Fasteners, Inc., 672 F.2d 1231, 1238-39 (5th Cir. Unit B 1982).

See e.g., Rollick v. Collins Pine Co., 975 F.2d 1009, 1014 (3d Cir. 1992).