CHEAT SHEET

- Introverts. People who recharge by being alone, introverts, comprise up to 50 percent of the population.

- Extroverts enamored. Corporate America places great value on extroversion and its associated traits like self-promotion.

- Personality bias. While personality bias may be unconscious, it is bad for business and reflects poor leadership.

- Introvert incentives. Both organizations and legal departments benefit by recognizing and using the unique strengths that introverts can bring to the workplace.

There are two races on earth. Those who need others, who are distracted, occupied and refreshed by others, who are worried, exhausted and unnerved by solitude as by the ascension of a terrible glacier or the crossing of a desert; and those, on the other hand, who are weary, bored, embarrassed, utterly fatigued by others, while isolation calms them, and the detachment and imaginative activity of their minds bathes them in peace.

GUY DE MAUPASSANT, 88 Short Stories

Shy. Quiet. Socially awkward. Reserved. These terms are commonly used to describe a large section of the population who identify as introverts. Such descriptions and associations, it turns out, are incorrect, misleading, and a disservice to both the individual and the organization.

As a threshold matter, shyness and introversion are not synonymous; rather, these are two entirely separate aspects of a personality. While introversion is a preference for solitude or intimate settings, shyness is anxiety or discomfort in social situations. Both introverts and extroverts can be afflicted with shyness, and people can be generally shy or situationally shy. Marti Olsen, author of The Introvert Advantage, explains that “[s]hyness is not who you are (like introversion), it is what you think other people think you are.” Or as put by Dr. Bernardo Carducci, professor of psychology at Indiana University Southeast, “If you see two people standing by a wall at a party, the introvert is there because he wants to be. The shy person is there because he feels he has to be.”

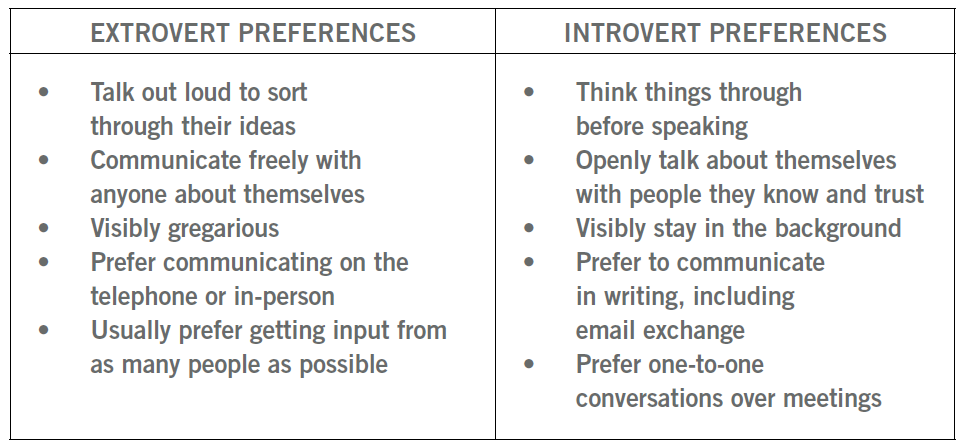

Introverts lose energy in social interactions and highly stimulating environments and require time alone to recharge. Extroverts, on the other hand, gain energy from socializing and need outside stimulation to feel content.

Likewise, being an extrovert does not guarantee fine-tuned social skills. As pointed out by occupational psychologist Felicity Lee, someone “can be an extrovert or an introvert and be very aware and socially skilled. Or they can be very unaware. Extroversion has nothing to do with emotional intelligence.”

Also, unlike specific personality traits such as friendliness or anxiety, introversion or extroversion are temperaments: a fundamental aspect of one’s disposition that influences personality and behavior. Introversion and extroversion are largely static, real, well recognized, and according to Olsen, considered “the most reliable construct of temperament” with a genetic component.

The classic distinction between the two temperaments is that introverts lose energy in social interactions and highly stimulating environments and require time alone to recharge. Extroverts, on the other hand, gain energy from socializing and need outside stimulation to feel content. While it may be easy to spot an introvert at a cocktail party, as one who is engaged in an intense conversation with one other person or simply listening to others talk in a group, introverts are not as readily apparent in the workplace. Classic introversion at work can display as one who is thoughtful and slow to speak up. This is in contrast to extroverts, who talk through a problem in real time and are typically motivated by public recognition. Yet some introverts are not immediately identifiable because they are used to acting like extroverts.

It is widely believed that one-third to as much as one-half of the population is introverted, with men and women comprising roughly equal parts of each group. This means it is virtually certain that any given legal department has some portion of introverts within it. And introverts can be found in every field and all levels of corporate hierarchy. Warren Buffet, J.K. Rowling, Michael Jordan, and Marissa Mayer all self-identify as introverts. Studies reported by Jennifer Kahnweiler, author of The Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet Strength, show that a full 40 percent of executives are introverts.

Corporate America’s bias in favor of extroverts

Assume for a moment that one-third to one-half of an organization’s workforce is left-handed. In this hypothetical, the organization engages in some of the following behaviors:

- Praises the ability of the righthanders to use their right hand with dexterity;

- Signals that this ability is very important for success;

- Sets up workspaces (keyboards, PCs, etc.) in a way that favors right-handers;

- Offers tuition reimbursement, workshops, and classes for lefthanders to learn to use their right hand;

- Encourages the left-handers to take advantage of these perks;

- For those left-handers reluctant to sign up for the workshops/classes, notes their lack of enthusiasm as an “opportunity area” on their performance reviews;

- Equates such lack of enthusiasm to deficiency in leadership skills and/or performance; and,

- Suggests to the left-handers that if they want to be seen as an up-and-coming leader, they must try to use their right hand more often.

The fallout from such a system is axiomatic, and some of the following consequences are inevitable:

- Subpar performance of the lefthanders who, under pressure, pretend to be right-handed, further compounding the misconception that left-handers suffer from a “performance” deficiency.

- Unfairness by creating an uneven playing field that gives the righthanders an undeserved and unjustifiable advantage.

- Resentment and drop in job satisfaction, ultimately leading to disengagement of the left-handers.

- As a result of the disengagement, loss to the organization of optimal use of the skills/talents of a significant portion of its employees — the left-handers.

- Shrinking of talent and leadership pools because left-handers, perceived as having performance deficiencies, are excluded from consideration.

- Incorrectly signaling to righthanders that they are uniquely suited for growth and leadership when, in reality, there is no correlation between being right-handed and being a good performer or leader.

If one were to swap the left-handers with introverts, this hypothetical becomes a reality. Such a system, it appears, has become ingrained in our workplace culture and is routinely enforced and promoted in corporate America. The widespread existence of the bias is shown in studies cited by psychologists, writers, and bloggers, and affirmed by the 10 GCs and other leaders interviewed for this article. When asked if there was a strong bias in favor of extroverts in corporate America, Dr. Rohini Anand, the senior vice president of corporate responsibility and global chief diversity officer of Sodexo, responded “absolutely.” Numotion’s General Counsel Tim Casey agreed, saying, “All leaders want to believe that they are running a meritocracy, but that is not always true because there is a strong bias in favor of extroversion.”

Perhaps the bias is not intentional or conscious. As noted by CBRE Executive Vice President and General Counsel Larry Midler (who identifies as an extrovert and oversees approximately 150 lawyers globally), this bias may be unconscious because we have been conditioned to assign greater value to extroverted behavior, often confusing this with good performance. Because of this mistaken association of charisma or gregariousness with good leadership or performance, bias leads organizations to fill leadership positions with individuals who display such traits, he says. This, adds Midler, is ironic since boards and CEOs need, more than ever, a GC who is a thinker, a subject matter expert, and a deliberate and serious person — all of which are predominantly introverted traits.

So how and why did we, as a society, acquire this bias in favor of extroversion? Susan Cain, author of the best-selling book Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, opines that the bias was born and continues to flourish in corporate America because we have moved away from valuing character and shifted to valuing personality. Therefore, we are impressed and awed by charisma, salesmanship, enthusiasm, and gregariousness. We see little value in substantive knowledge, or thoughtfulness.

Extroversion is an enormously appealing personality style, but we’ve turned it into an oppressive standard to which most of us feel we must conform.

— Susan Cain

Yet, Cain points out, research shows no correlation between the most talkative person in the room and the one with the best ideas. Indeed, some of our best performers and leaders have been and are introverts. The interviewed GCs, and the materials reviewed for this article, expressly discredit and deny that extroversion is an essential leadership skill. Rather, the key leadership skills identified by the GCs include being perceived as trustworthy and fair, making tough decisions, and having a grounded and thoughtful demeanor.

It has long been recognized that we all have a natural temperament climate in which we feel more comfortable, perform our best, and maintain a crucial balance for our species.

— Marti Laney, PSY.D.

In contrast, the group uniformly felt that charisma and magnetism were non-essential to leadership. Assertiveness was also not valued as a leadership skill by the GCs. Self-identified introvert Robert Falk, the general counsel of The Truth Initiative, points out that while extroversion is not generally an essential leadership skill, in an organization where the entire leadership team is extroverted they “seek out their own.”

Speaking highly of the skillset of introverts on their teams, the GCs described this group as hard workers with a high level of subject matter expertise, credible and reliable, even-keeled, thoughtful, deliberate, analytical, methodical, critical thinkers, focused, disciplined, cautious, great problem-solvers, and good listeners. Prometric Senior Vice President and General Counsel Michael Sawicki, who identifies as an extrovert, points out that introversion, especially for an attorney, has no bearing on performance and should not limit an attorney’s career advancement because the ultimate value of an attorney lies in subject matter expertise, other legal skills, and the ability to communicate with the organization.

Impact of this bias in the workplace

Irrespective of why and how we got here, it behooves us to recognize the pervasiveness of this bias as well as its harmful effects both on the individual and the organization. For the individual introvert, the fallout demonstrates itself in terms of trust, fairness, job satisfaction, career growth, and comfort. For the organization, it translates into a profound impact on elements essential to organizational success such as performance, engagement, culture, talent retention, and leadership development.

The bias leads to tremendous behavioral pressures on the introverted employees who are constantly signaled to “fix” their introversion. Introversion, it seems, is not viewed as a temperament but instead a pathology for which the extrovert-enamored organization or leader must find treatment. Introverts speak of discomfort, disengagement, and distress at being coaxed to masquerade as extroverts or ignored because they don’t fit the sought-after extroverted mold. Introverts such as Falk speak of “an emotional drain” as a result of societal pressure to “act” as an extrovert and often yearn to return to solitude to recharge. Self-negation can be exhausting and introverts often use that very word to describe the impact of the bias upon them. Dr. Anand affirms the sentiment, saying that forcing employees to hide aspects of their temperament, or any other individual element, would be an exhausting experience for the employee and can lead to burnout and resentment that results in loss of engagement and productivity. She urges that employees feel not merely comfortable, but empowered, to bring their true, authentic, and whole self to work and notes that “in order to be effective, a leader must seek engagement from each person on the team and that requires a strong awareness of everything that makes that person an individual.”

Our culture made a virtue of living only as extroverts. We discouraged the inner journey, the quest for a center. So we lost our center and have to find it again.

— Anais Nin

The pressure on introverted employees can be felt in seemingly minor office “rules” such as prohibiting or discouraging the closing of office doors or the pressure to socialize in large groups. Pointing to such pressures as being “draining,” introvert Dee Drummond, the group general counsel of MarketSource, Inc., speaks of his need to close his office door because “[t]hat is how I work best” and “interruptions, noise, or traffic outside my office is distracting to me.” Introverts also speak of a pressure to focus their energy on aspects that don’t come to them naturally, such as socializing, networking, and self-promotion. The bias is also often reflected by the recent trend toward extroverted preferences such as team projects, open concept offices, and the pressure to promote your personal brand.

In group discussions, extroverts and their ideas often get the most attention by sheer force of personality, particularly if the extrovert is in a position of power. A department or company may overlook better ideas that were quietly presented by introverts, or that were not communicated at all due to an introvert’s discomfort with the extrovert bias. As Sawicki points out, it harms an organization to exclude introverts from development efforts or important tasks in favor of employees who speak up.

Where do we go from here?

It is imperative that leaders take a hard look at the culture, work habits, behaviors, environments, and performance criteria of their organizations. They need to make changes that ensure the stigma against introversion is eliminated culturally. These changes will give both introverts and extroverts the space, power, and freedom to bring their entire and genuine self to work and demonstrate their individual talents. The following suggestions, based on reported studies and the findings and opinions of GCs and other experts may lead us to the desired state of balance:

- Acknowledge the bias. Although pervasive, self-diagnosis of the bias can be hard, searching conscious or unconscious assumptions can help. The bias may be reflected in a notion that gregariousness, charisma, or “people skills” are essential to leadership. Or it may manifest in behaviors such as hiring or promotion based on personality and likeability; devaluing of substantive elements such as hard work, focus, technical or subject matter expertise, dedication, thoughtfulness, or credibility; associating a lack of desire to socialize with performance deficiency; refusing to accept a style of work that is unfamiliar or does not fit the preconceived mold; and imposing the leader’s style and expectations on the team.

- Watch for red flags and blind spots. A leader who fails (or refuses) to see the value of what each temperament brings to the table, gets frustrated when an individual does not fit the leader’s preconceived mold, looks for buddies or best friends within the team, or insists that the team work and behave in the leader’s mold must know that these are red flags indicative of the leader’s intolerance. Nixon Peabody’s Director of Diversity and Inclusion Rekha Chiruvolu suggests that leaders should be willing to see things that may be unpleasant to their preferences. They need to acknowledge their “blind spots” in the treatment of introverted team members because the awareness can help disrupt introvert assumptions. An extroverted GC must be especially cognizant of the tendency to get frustrated with an introverted team member because that individual’s behavior and style of work is going to be very different from the GC’s. Another blind spot is a GC’s selection of friends within the team, notes Drummond. This can manifest in frustration at an individual who does not behave in a way the GC expects. Sawicki seconds these concerns and cautions GCs against imposing their own style on the team. The onus is on the leader, Sawicki stresses, to reach out and select qualified individuals for key assignments and to not be swayed by the person who frequently volunteers or who, by force of personality, pleases the GC. This duty is reiterated by Chiruvolu who calls this a key leadership responsibility and adds that absence of such awareness is a flaw that does not make for good leadership. Extrovert Eric Reicin, the general counsel of MorganFranklin, cautions leaders to not let their personal biases regarding temperaments lead them to select the wrong individual or limit the opportunities of non-conforming team members.

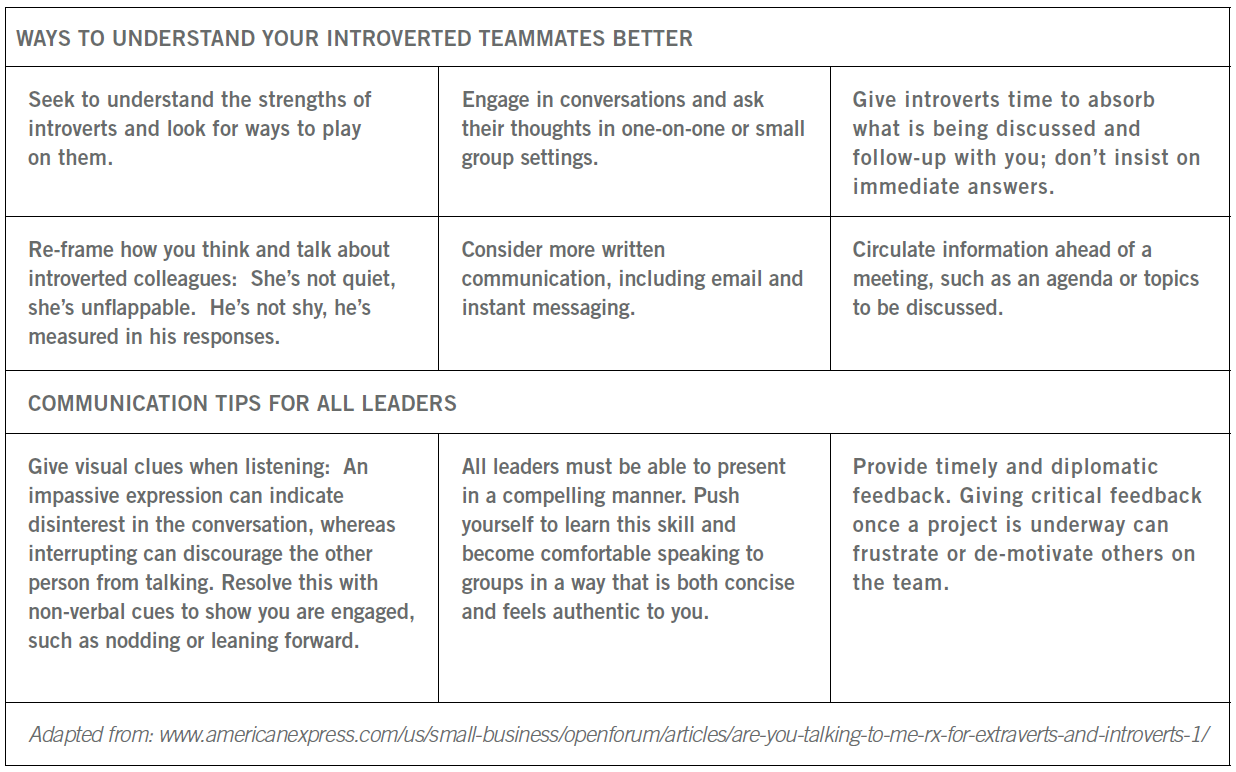

- Get to know each individual on your team. A leader committed to learning about each team member will learn important details such as the level of praise an individual seeks or the frequency and types of interactions that are optimal for performance. For instance, introverts generally don’t need to (or perhaps desire to) engage and interact as much as the extroverts. The same goes for the level of socializing that may be desired or enjoyed by an individual. Rather than mandating socializing, Casey suggests letting each individual find his or her own way of connecting with the client. Not every happy hour or dinner needs to be attended. Introverts usually prefer smaller or one-on-one interactions. It would also be a strategic mistake and a severe misuse of talent to ignore the differences in temperament. Hawthorne Caterpillar’s General Counsel Jeffrey Boman, who identifies as an extrovert, suggests that GCs harness the strengths of introverts by engaging in one-on-one conversations, anonymous surveys, seeking written feedback, and sharing meeting agendas ahead of the meeting. These types of actions would help the GC manage each member differently and, most importantly, maintain in the forefront of priorities what is truly related to performance or leadership. While the GC can and should coach and challenge the team with different projects, Casey says, this must be accompanied with a message that “you have their back” and not “you need to fix this about you.”

- Give each person room to be themselves and eliminate introversion stigma. Urging leaders to value what is truly essential to performance and leadership, Tom Merchant, the general counsel of Legg Mason, asks that GCs give space to each person on the team — introverts and extroverts — and let each person work in her or his own style without imposition of the GC’s style on the group. Especially for a lawyer, notes Merchant, subject matter expertise is far more important than being a social people person or a charismatic talker. Offering an interesting perspective, Lisa Kahlman, chief of staff to the Ultragenyx CEO, and the former general counsel of Ultragenyx, suggests that the leader’s obligation to accommodate the team members is greater than the team’s obligation to accommodate the leader. The stigma can also be eradicated by eliminating rewards for behavior that is not truly related to performance such as praising social skills or, in other ways, signaling that there is an advantage to extroversion or a problem with introversion.

- Embrace and recognize the value of differing temperaments. This is a difficult thing to do for even the most open-minded individual, says Otto Kroeger in his book Type Talk at Work. Going well beyond tolerating or patronizing, Casey proposes wholeheartedly making room for the richness that lies in the differences and calls this “job number one” for the leader. A GC who does not do so, says Casey, is not a leader but merely someone in a leadership role. Moreover, notes Casey, when people are devalued or disrespected, what you get is merely what’s on the job description — nothing more.

Other GCs strongly echo Casey’s sentiments recognizing that embracing the spectrum of different temperaments means valuing what each individual brings to the table irrespective of the leader’s personal preferences. Reicin pointed out that a leader “must make sure that all members on your team know that their viewpoints are valued,” whether the leader communicates this in public or private to a team member. Of course, this becomes especially more important (and difficult) if the GC is extroverted. The GC, not being familiar with the traits of introverts, will tend to devalue those traits. Embracing and valuing both temperaments would also alleviate the pressure on introverts to “fake it.” Because temperamental traits of extroversion and introversion traits are real, recognized, and indelible, it would be fundamentally unfair (and ineffective) to insist that a person acts in self-negation and adopt behavior that is contrary to their temperamental makeup. After all, as Marco Alvera says in his TED talk, The Surprising Ingredient that Makes Businesses Work Better, fairness is the “secret sauce” that drives employee engagement and high business performance.

- Emphasize metrics that are truly related to performance or leadership. Paying attention to actual performance metrics, not charisma, talk, or socializing, can also help the leader recognize and value strengths in each person. Midler speaks of the dangers of a GC’s refusal or failure to look beyond the charismatic talker who is always reaching for the microphone. Specifically addressing extroverted GCs, he stresses the need to give opportunities to individuals who are not like the GC in temperament and advises against pigeonholing introverts into roles limited to support and subject matter expertise. That would be a mistake, he says, when the introvert you exclude may be, after all, the better lawyer and leader. The dangers of being charmed by the charismatic talker and risk-taker are apparent even beyond the legal department realm. The managing director of Eagle Capital, Boykin Curry, in his 2008 Newsweek interview, noted that the 2008 crash was a result of too much power in the hands of aggressive risk-takers, a sentiment echoed by Dr. Vince Kaminski, a professor at Rice University. He notes that “The problem is that, on one side, you have a rainmaker who is making lots of money for the company and is treated like a superstar, and on the other side you have an introverted nerd. So who do you think wins?” Referring to these testimonies, author Cain wonders “what would have been different had financial leaders heeded such warnings from ‘the cautious types.’”

Leaders who don’t listen will eventually be surrounded by people who have nothing to say.

— Andy Stanley

Conclusion

No company or leader wants to underuse their employees. But by discounting or ignoring the skills of the introverted population of their workforce, this may be precisely what is taking place. Each member of the legal department — introverts and extroverts, general counsel and supporting attorneys — have a role to play in rolling back this trend. Like most opportunities for change, the first step is to identify the issue within one’s team or department. While shifting corporate culture is a time-consuming and labor-intensive exercise, for all the reasons outlined in this article, in-house counsel can and should take actionable steps toward creating an environment that fosters all temperaments.

FURTHER READING LIST

Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking, Susan Cain

Key points of Quiet are also available in a TED Talk.

The Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet Strength, Jennifer Kahnweiler

“Extroverts destroy the world,” Kyle Smith, New York Post, February 5, 2012.

Consciously ‘Unconsciously’ Bias: Part One, Sally Schott, March 1, 2018.

Consciously ‘Unconscious’ Biased: Part Two, Sally Schott, March 22, 2018.

Death by Leadership, Karen Joy, March 19, 2018.

“How to Get a Promotion When You’re An Introvert,” Sarah Greesonbach, March 28, 2018.

“The Art of Managing Risk” Steven Pearlstein, The Washington Post, November 28, 2007.