CHEAT SHEET

- Stricter policies. Jurisdictions all over the world are expected to continue to intensify, clarify, and tighten policies surrounding code of conduct and whistleblower legislation to set a clear expectation for how companies should handle a sexual harassment claim.

- Official channels. It’s important to establish multiple channels for reporting sexual harassment. Give employees the opportunity to report up their own chain of command, to someone in HR, or to anyone in upper management.

- Training in India. In India, training starts at a cultural level. In some instances, for example, organizations put on a series of plays to educate people about the impact of sexual harassment in the workplace.

- Retaliation consideration. Both the accuser and the accused should be reminded at every conversation about the company’s anti-retaliation policies and warned that any attempt to retaliate in the investigation will lead to discipline, if not discharge.

The #MeToo movement, which gained international notoriety following the sexual misconduct allegations of a well-known Hollywood producer, has become a digital outcry for women and men who refuse to be silent about inappropriate behavior in the workplace and beyond. While some of us have sat through trainings on what constitutes workplace harassment, policies and procedures for reporting and responding to such claims vary widely from company to company — and from country to country.

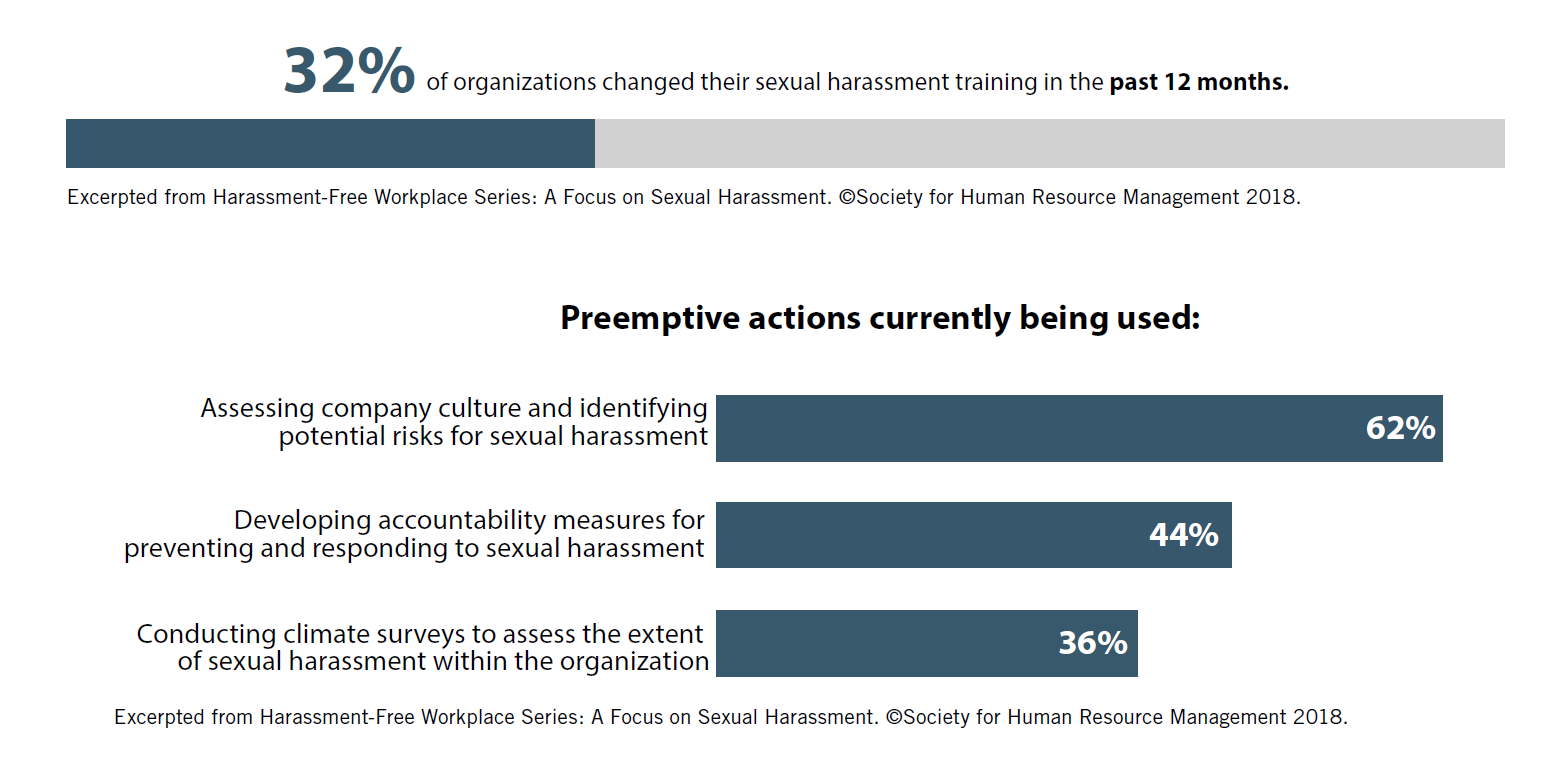

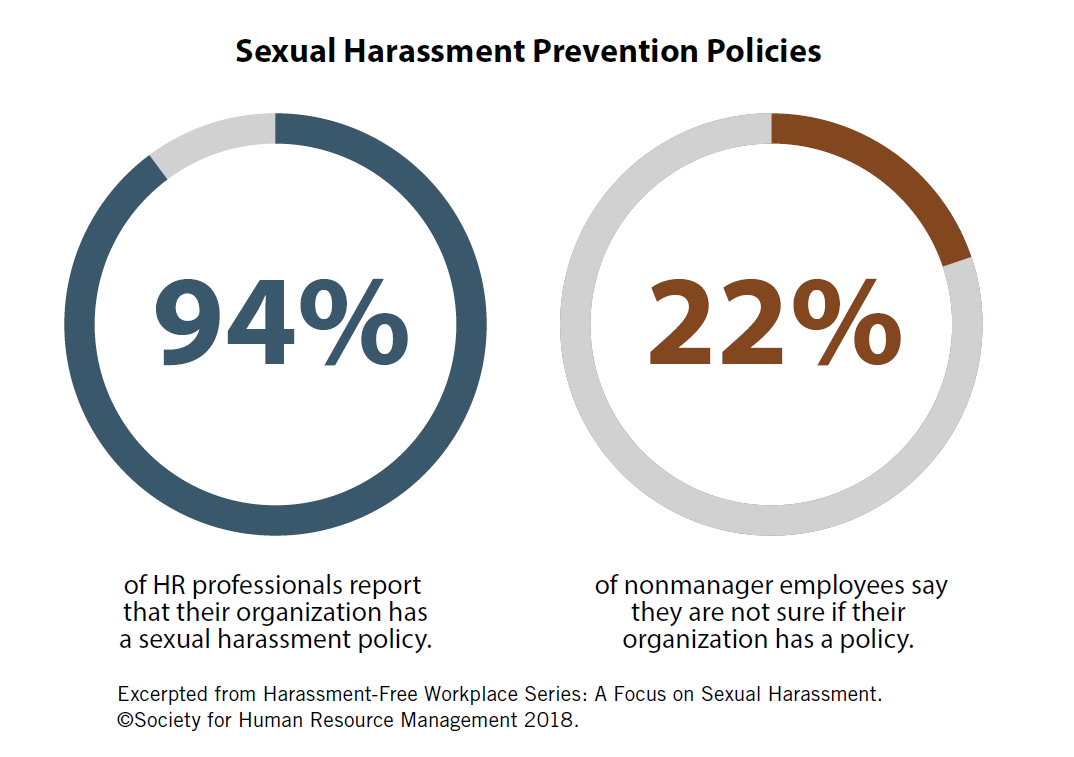

In fact, research by the WORLD Policy Analysis Center at UCLA found that 68 countries do not have any workplace-specific protections against sexual harassment. What’s more, a staggering 57 percent of HR professionals believe that unreported sexual harassment incidents occur to a small extent within their organization, according to a report by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM).

With global news breaking almost daily with allegations of abuse, or the firing of another accused executive, companies are taking a hard look at their employment policies. But what needs to change? How can the legal department help? And how should companies respond to claims of sexual harassment and all behavior that causes fear or anxiety in the workplace?

Here, four in-house counsel from four different areas of the world attempt to answer these questions and more, discussing the current sexual harassment laws that exist in their jurisdictions; how they anticipate laws could change as a result of the movement; and what in-house counsel can do to prepare for the possibility of increased reports of sexual harassment, including creating a culture that encourages — and does not deter — people to step forward.

Panel

AXEL VIAENE

Axel Viaene is group general counsel and company secretary of GrandVision based in Schiphol, the Netherlands. Previously, Viaene served as EMEA legal director for Starbucks from 2003 until 2013, based in Amsterdam. He has been a member of the New York Bar since 1998, and served as president of the board of directors of the European Chapter of ACC during the 2009-2010 term. He received an LL.M. from the University of Chicago Law School and is a graduate of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Law School in Belgium.

LORI MIDDLEHURST

Lori Middlehurst is the director and assistant general counsel of VMware, a multinational software company. She leads its Global Employment Law Group, with lawyers in the United States, EMEA, and Asia Pacific. She is the vice president of ACC New South Wales and is active on the CLE and Diversity and Inclusion subcommittees. She has just joined the board of ACC Australia, and also contributes to ACC globally as the co chair of the International subcommittee of ACC’s Employment and Labor Law Committee.

MAHALAKSHMI RAVISANKAR

Mahalakshmi Ravisankar is a seasoned compliance professional, with over 30 years of corporate experience in leading multinationals, such as Unilever, Diageo India, and ABB India, and has earned her LLB and CS degrees. She has diverse experience in setting up compliance and governance framework in companies, such as Marico India, Times of India, and Beiersdorf India. She is currently working on a project COMVERVE, a prototype for implementing compliance programs through effective communication and community initiatives.

ELIZABETH BILLE

Elizabeth Bille is general counsel of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). SHRM is the world’s largest HR professional society, representing 290,000 members in more than 165 countries. Before joining SHRM’s legal department, Bille served as counsel to the vice chair of the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), where she worked on complex employment discrimination litigation and the development of EEOC regulations and enforcement guidance.

THE LAW OF THE LAND

ACC: How have sexual harassment laws changed as a result of the #MeToo movement and how do you anticipate they’ll change in the future?

Elizabeth Bille (United States): I think the #MeToo movement has really provided a catalyst for organizations to do a lot of self-reflection. They’re looking at their harassment policies, not just regarding sexual harassment, but harassment in general, and asking themselves: Are we going far enough in prohibiting not just what constitutes legal harassment, but other behaviors that could be precursors to harassment? In other words, are they [the policies] covering the scope of behaviors that are detrimental to our culture and could pave the way for future legal harassment claims?

Further, organizations are really taking a hard look at their investigation procedures. Specifically, how many channels do we have for people to report? To whom are we asking that they report? Do we have an anonymous option? What happens once we receive a complaint? How promptly is it being investigated? Who is doing the investigation? Is that investigation happening in an objective way by someone who has no stake in the outcome?

I think the third thing organizations are looking at is, “Are our individual employees safe to come forward and report?” You can have the best reporting mechanisms in the world, but if there is subtext that you should not use them, then they do an organization absolutely no good. How do we encourage employees to report good faith concerns, and convey the message that we truly want to know?

Axel Viaene (EMEA): I think that the jurisdictions in EMEA, as well as in the rest of the world, will continue to intensify, clarify, and tighten policies surrounding code of conduct and whistleblower legislation to set a clear expectation for companies about how they should properly handle a sexual harassment claim. When the European Parliament met about #MeToo earlier this year, it was just sort of an opening shot. I think this will very probably lead to an intensification of compliance-related legislation — which, by the way, I think is a very good thing. The clearer these things are Europe-wide, and worldwide, the better.

However, I think you shouldn’t solely see it in a sexual harassment perspective. We should be thinking of compliance and code of conduct in general. I serve as global general counsel for GrandVision, but we’re located in EMEA and, of course, this is our backyard. What I have seen is an intensifying of legislation in that respect, which is a very good development. The EMEA jurisdictions are taking this more and more seriously. For instance, France recently implemented detailed new legislation on code of conduct and compliance.

Mahalakshmi Ravisankar (India): After 1997, following the implementation of mandatory guidelines by the apex court in India, known as the Vishaka Guidelines, sexual harassment policies became a buzzword for precaution, not protection. However, in 2013, the Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act 2013 was passed in a landmark ruling in the history of the Indian judiciary, wherein for the first time, regulations gave authority to local management to not just deter sexual harassment, but provide authority to organizations to police all kinds of insensitive behavior, manifesting as sexual harassment in the workplace.

The law expanded the boundary of sexual harassment legislation beyond the corporate set up, making the employer responsible for its adjudication, irrespective of the size and nature of an entity, covering even the domestic workers. The law is landmark in bringing the courtroom to the boardroom — vesting the employer with all the powers of a civil court and making management the custodian of the law vis-àvis the stakeholders.

Lori Middlehurst (Australia/APAC): I look after employment matters for the Asia Pacific region, which in our world contains about 15 different countries with hugely varied cultural, religious, historical, and linguistic backgrounds. You start at one end, with Australia and New Zealand, common law countries that have had sexual harassment laws for more than 25 years. Then on the other end, you have a lot of countries in Asia that may not have laws or just generically prohibit discrimination. Singapore still has voluntary guidance — meaning that it does not currently have any enforceable sexual harassment standards, although it’s illegal to discriminate. Taiwan and South Korea, however, both have detailed laws that require localized training in local language. And then you have India, which has just developed this extremely elaborate regulatory framework for sexual harassment in just the last three or four years. There is a lot of room for improvement in terms of legislative initiative in this region, and I think we will see frameworks being developed.

Multinationals can’t just rely on a global US-centric policy. You have to be specific about the law in each country. When setting policy, I think it’s important to choose language that resonates broadly. Multinationals have to look for different ways to explain what your expectations are, as well as “advertise” the support provided to employees who experience or witness harassment.

We have a high standard, and we apply that high standard across the board in terms of our behavioral expectations. But if that standard is at odds with societal norms in a particular country, then we have to work harder to inculcate it and make sure that employees know that we want all of them to experience a safe and respectful environment. At-will employment is not the norm in APAC, so we also need to make sure that our investigative and disciplinary processes meet standards of due process, or regulatory requirements across the geography.

PREPARING FOR THE AFTERMATH OF #MeToo

ACC: What strategies should in-house counsel implement to prepare for the rise of reporting as a result of #MeToo?

Middlehurst: I think that it’s [#MeToo] really shaken companies out of their complacency. You’ve got to really look at what you’re doing, and then take a new look at the components that you used to try to prevent harassment and maintain a harassment-free environment.

Establishing official channels is so important in doing that, but how do we make people more aware? It’s easy to create a channel, but the hard part is actually getting the people to come forward. Then you have to look at the engagement between your company and employees. You’ve got to create a level of transparency where employees understand how decisions get made, and that they can see, in each of the places where those decisions are getting made, that decisions are getting made fairly and based on the facts. You have to create this environment where employees can trust their management, and you have to work at that all the time.

Bille: #MeToo has really reinforced the importance of giving employees multiple channels for reporting. At SHRM, we discuss this often: Give employees the opportunity to report up their own chain of command, give them an opportunity to report to someone in HR, and give them an opportunity to report to anyone in senior management. In addition, establish an external anonymous hotline. I think having the anonymous hotline in particular is critical because, not withstanding assurances that individuals won’t be retaliated against, some people simply do not feel comfortable having a face-to-face conversation about something that is as sensitive and potentially embarrassing as a potential sexual harassment complaint.

ACC: If an investigation does occur, how do you ensure due process?

Middlehurst: Companies must have structures in place so that all employees understand that the company is not acting on presumption of guilt. It is important to set those expectations right away with individuals who come forward. It’s important that the employees involved understand the country requirements for an investigation as well — that the process may be different from what they see on American TV.

Viaene: Of course, when something like this happens, where an accusation is launched against a person, the easiest solution for the company is to just fire the person without putting too much energy in the investigation. That is wrong. It is the company’s duty to investigate properly, to put in adequate resources, and to report transparently and professionally.

Bille: Companies still have to be very careful in their zeal to aggressively eradicate harassment and deal swiftly with allegations. They cannot swing too far in the other direction and not afford the accused due process. You have to investigate. There are very often two sides to every story and, therefore, it is critical to engage in the investigation before any disciplinary action is taken. It may be a very short investigation if there is overwhelming evidence, but an investigation needs to be done. Everyone deserves due process, both the accused and the accuser. In an organization that does not afford due process to the accused, they may do so at their peril.

TRAINING & COMPANY CULTURE

ACC: What purpose does training hold in preventing sexual harassment? How frequently should sexual harassment training occur?

Viaene: Tone at the top. I mean it really starts there. Then, make sure that your policies surrounding sexual harassment are clear and make sure training is implemented both face-to-face and through e-learning. Make sure this training is not too legalistic and is repeated to ensure accountability.

I think it’s important that training occurs at least once a year and for every newcomer as well. So as part of your induction, you take the training. But it is must be part of the culture of the company. I think that is probably one of the most effective training tools. It shows the new people, the junior people, how you should conduct yourself within a company and how to treat people in a business context. That’s still the best training there is.

Ravisankar: In India, training starts at a cultural level. For instance, in Bangalore, we have a wonderful series of performances in a forum format where we enact situations, which are promulgated for sexual harassment. We create that kind of a scenario, and then the people who are watching the play come join the performance, and change the outcome.

So when people see that there are scenes that are being enacted which they can relate to — either because they themselves have gone through it or somebody else has gone through it — then they’re actually getting an opportunity to come and correct the situation. That’s very, very effective for them. There are many women who go through sexual harassment, but there are no forums to gather them for any kind of counseling that may be available.

Middlehurst: I’ll echo the comments above — in India we have had a grass-roots effort to educate people through the use of plays, written and performed by our own employees. This has been extremely popular and a well-received vehicle for imparting knowledge. In Australia, that would never work. Australians are much too cynical and prefer more direct communication. The important message about training is that one size and type does not fit all — it needs to be relatable, culturally appropriate and not simply a tick-the-box exercise.

ACC: Similarly, anti-retaliation policy is especially top-of-mind when thinking about sexual harassment policy. How do you ensure that you create a culture where employees do not feel they will be punished for speaking up?

Bille: I think there are few things that companies can do to prevent retaliation. Obviously, they should have as a baseline matter, a very strong anti-retaliation policy that is communicated regularly. Both the accuser and the accused will be reminded at every conversation about anti-retaliation, and that any attempts to retaliate unlawfully against someone who is participating in the investigation would lead to swift and serious discipline, if not discharge. That’s obviously the baseline step.

Another important aspect is taking action when retaliation does occur. This requires absolute resolve from the very top of the organization on down that retaliation will not be tolerated. Employees should see that someone who has taken retaliatory steps against an accuser is disciplined or discharged — and of course sometimes there’s confidentiality, you can’t always understand the reasons for why an action happened. But if they see it happen, word will spread very fast that the company means what they say.

Third, as a practical matter, it’s always an effective practice whenever an allegation of discrimination or harassment has been filed that the accuser, if they are in the same supervisory chain as the accused, be removed. One of them should be removed from that supervisory chain or otherwise insulated from the other to prevent the possibility of future retaliation, particularly while the investigation is pending.

You need to do this in a way that doesn’t constitute retaliation against the accuser. For example, if there is an allegation that a manager is sexually harassing their subordinate, you would either reassign the manager or you would move the individual accuser to another reporting chain or another part of the building. Again, not in a way that’s detrimental to that person, but in order to protect them from interactions that could either be retaliatory or would facilitate possible continued harassment. You’ve got to stop harassment. You’ve got to prevent retaliation when you receive a complaint.

Viaene: Europeans refer to the United States as having the principle of “at will” employment but do not always realize that the US system also has a lot of employee protection built in. There are a lot of ways that employees can sue their employer for wrongdoing. But Europe has a very protectionist employment law culture, so in many cases there are no specific anti-retaliation laws because the employee is already extremely well-protected by the system.

I fear there is really no one-size-fits-all solution for building such a culture. It is a long-term effort consisting of tone at the top, training, effective communication, leading by example, accountability, and reporting. If you do this right, the right culture will emerge. You will also need to maintain this effort or the culture will quickly evaporate. A good test to gauge the health of your company culture is to keep your ear to the ground and listen to the stories that circulate. A lot of employees, in most cases wrongly, base their perception and their consequent actions not as much on policies, training, and facts but on what they hear in the informal circuit.

TECHNOLOGY & #METOO

What role will technology play in the #MeToo movement and how can legal departments ensure a fair, safe process?

Ravisankar: The way I see #MeToo movement right now is more like wearing a digital badge. #MeToo is a collective. It is showing that sexual harassment is an issue that cannot be addressed by one organization alone. It needs a joint-action plan from the government, from the civil society, from NGOs, and also from organizations worldwide.

Viaene: I hope that this will motivate people to abandon their fears, pick up that phone, and use the whistleblower hotline that I’m sure is available in their company, and report this behavior rather than being afraid of retaliation and not reporting it. I think that that will happen, and I also hope that will happen. In that respect, the #MeToo movement will hopefully help persuade victims of this sort of illicit behavior to really speak up so it can be addressed.

Bille: One way I see technology increasingly playing a part in the investigation of sexual harassment cases involves the evidentiary trail provided through technology. Whether it’s text messages, social media posts, email, photo sharing, or things of that nature, they are increasingly the types of evidence that general counsel and in-house counsel will be looking for — or may be presented to them as part of the investigation. It’s not always just the he said/she said anymore.

WHAT’S NEXT

ACC: Where do we go from here?

Bille: This is one area where we will see private industry really taking the lead in examining what’s happening, and maybe where things have fallen short in terms of internal responses, and then taking more aggressive steps to define the culture that they want to have. Further, they’ll ensure that everyone from the very top to the very bottom of the organization are held accountable to that culture and embrace that culture.

If they don’t, they will not be employed, even if they are the rainmaker of the organization. I think we’re going to see — whether it’s pressure from social media, the media, or consumers — that shareholders are going to really be focusing on this in a heightened fashion going forward. Based on that expectation and demand, organizations will likely refocus and reinvest in this issue.

Middlehurst: Technology companies like mine are in such a tough race for talent that there is no question that we need to be attractive to a diverse base in every geography where we have offices. If we don’t have a good environment for people to work in, we will never be able to achieve any kind of parity, or increase the number of women in our workforce. It’s an economic imperative. Many people who experience harassment, even if it is dealt with appropriately, will leave the company — that is a loss of a valuable resource. The #MeToo movement is a great reminder that we need to stop harassment from happening in the first place.

Viaene: I think social media is a godsend in that respect because it helps with transparency. It helps with democracy. Whenever something goes wrong, it can be put on social media with proof. Of course, provided that it’s not being abused. But it is important that these things can no longer be hidden. In the future, social media can help tremendously by rooting out this sort of behavior.

Ravisankar: I feel the #MeToo movement has actually expanded the bandwidth of the actions that needs to be taken in the workplace. In addition, many organizations have gone one step ahead and said it’s important for us to hire women, retain them, and ensure that the workplace environment is safe and condusive. It levels the playing field. If you’re playing football, you need to have a football ground. You cannot ask a woman to play football on a cricket ground.

Today, organizations are expected to play the role of a conscience keeper and a torchbearer for promoting mutual respect, trust, and dignity. For this to translate into meaningful action, legislation has to be married to the commitment of the corporations, the responsibility of the regulators, and the vision of the policy makers. This process will see many more #MeToo campaigns to come.