CHEAT SHEET

- Cooperation. The 11 largest corruption-related global resolutions between 2016 and 2018 involved multiple international enforcement authorities, including those in South America, Europe, the United States, and the Middle East.

- International double jeopardy. There is no recognized principle of “international double jeopardy.” Multiple countries could potentially bring charges against a company based on the same conduct.

- Extraterritorial laws. Most anti-corruption laws have extraterritorial reach; therefore, a company could be subject to prosecution anywhere it maintains operations.

- Global standard. When facing variations in legal requirements across jurisdictions, create a single global compliance program that addresses jurisdiction-specific issues.

The past two years have been an extraordinary period for anti-corruption enforcement. There have been seemingly countless newspaper articles and client alerts on costly investigations, huge settlements, and diving stock prices for companies that have not even been charged with a crime. While other extraordinary compliance developments — such as the General Data Protection Regulation, sanctions controls, and #MeToo — have grabbed headlines, corruption remains a top-of-mind risk for your management and board.

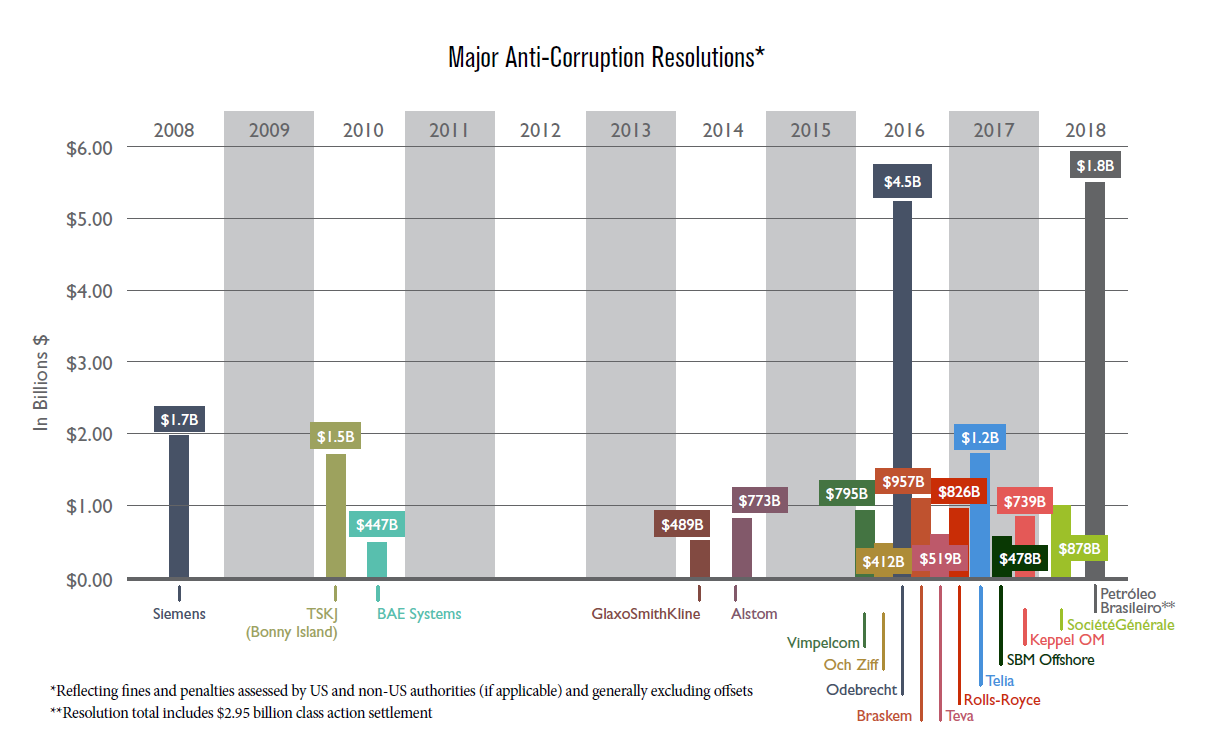

Let’s begin with a striking fact: The number of corruption-related global resolutions in excess of US$400 million has increased by more than 500 percent since 2016 relative to the eight years before that (there were no resolutions in excess of US$400 million before 2008). Between the highly publicized Siemens resolution in 2008 and the end of 2015, there were approximately five corruption-related resolutions totaling in excess of US$400 million, when non-US penalties and fines are considered: Siemens, BAE, KBR/Halliburton, GSK, and Alstom. Since 2016, however, there have been approximately 11 such resolutions, including the record-setting US$4.5 billion settlement in the Odebrecht case (subsequently reduced to US$2.6 billion due to Odebrecht’s inability to pay). This five-fold increase obviously begs the question: Is this a fluke or has the enforcement environment changed in some fundamental way? In this article, we argue that it is the latter and explain why the change requires all companies with potential exposure to global anti-corruption laws to reassess their compliance programs.

What accounts for this seemingly sudden surge in massive global enforcement actions? While there is always a constellation of factors, one of the most remarkable themes of recent cases is that they are almost all the product of multijurisdictional investigation and enforcement efforts. While US enforcement authorities have long cooperated with their counterparts in other countries, these efforts have become even more pronounced in recent years. For example, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) publicly thanked law enforcement colleagues and agencies in 18 different jurisdictions in press releases announcing the 2016 resolution with VimpelCom Limited. In 2017 alone, the DOJ received significant cooperation from approximately 20 different countries in Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) cases.

Perhaps even more salient, US and foreign jurisdictions are not only sharing information and cooperating in their investigations, but proactively coordinating global resolutions. Until relatively recently, the United States was the most active enforcer of foreign bribery laws, although there are both jurisdictional and practical limits on the conduct it can reach.

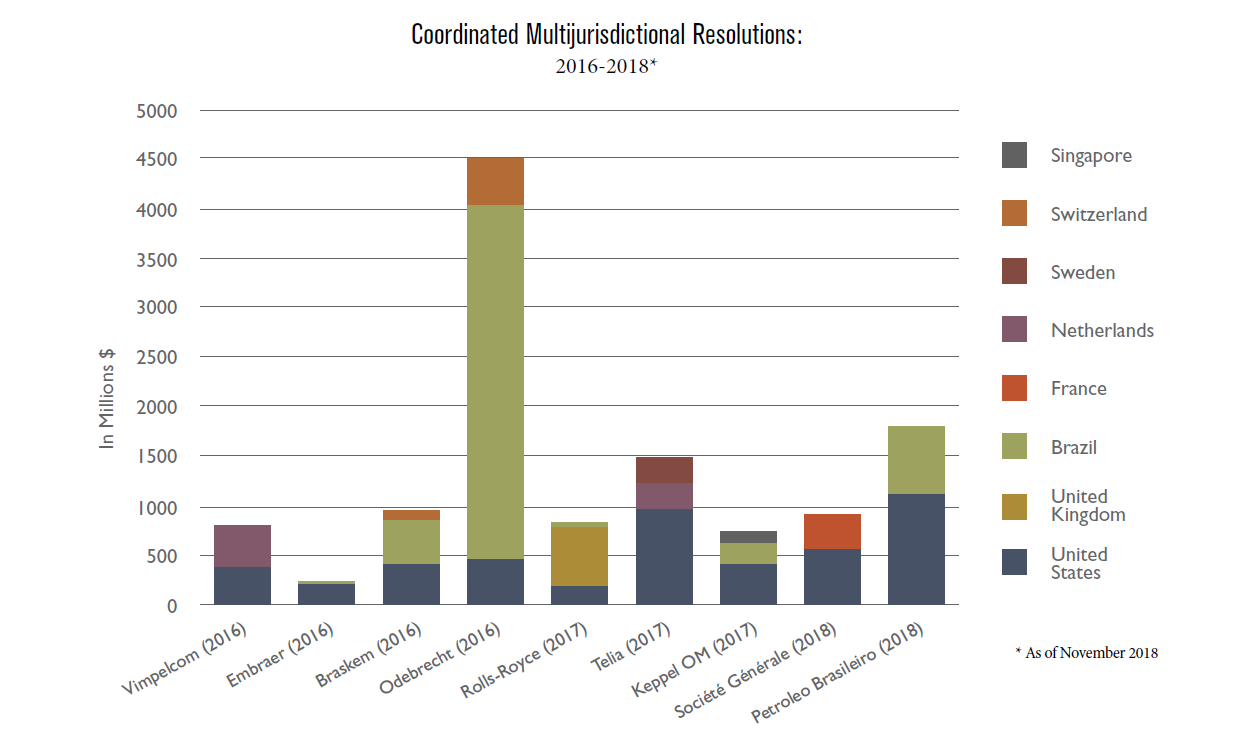

In recent years, however, the DOJ has increasingly coordinated resolutions with foreign enforcement authorities in FCPA cases. From 2016 through October 2018, the DOJ coordinated resolutions with foreign enforcement authorities in nine cases, more than twice as many as all prior years combined. The authorities included Brazil, France, the Netherlands, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Although not announced simultaneously, other jurisdictions such as Israel, the Dominican Republic, Panama, and Guatemala also brought follow-on enforcement actions against some of the same corporate defendants.

While many factors have contributed to this trend, including strengthened cross-border relationships and information sharing — as evidenced by the fact that in 2017, the DOJ assigned a prosecutor from the Fraud Section’s FCPA Unit to the United Kingdom’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) and Financial Conduct Authority to further enhance cooperation with those agencies — one major factor has been increased anti-corruption enforcement by foreign authorities. Companies with a multinational presence must therefore contend not only with multiple US enforcement agencies but also with multijurisdictional enforcement involving foreign authorities.

Apart from countries like Brazil, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, which have become repeat players in coordinated global resolutions with the United States, there are a number of other jurisdictions dedicating significant resources to anti-corruption efforts. China is in the midst of an unprecedented domestic anti-corruption campaign; a massive corruption investigation involving a state investment fund is still underway in Malaysia; and countries like India, Thailand, France, and Mexico have new foreign bribery laws on the books and are developing teams of prosecutors dedicated to fighting corruption. We should expect other jurisdictions to join the fray soon, and, with some exceptions, expect multijurisdictional cooperation and coordination to be the norm.

Obviously, the greater the number of active enforcers, the larger the number of cases we can expect. But it won’t just be growth in the volume of cases and settlements; instead, we should anticipate substantive changes in how we operate a compliance program. Below, we outline the most significant challenges we expect compliance organizations to face in the future based on the upsurge in anti-corruption cooperation, coordination, and enforcement globally.

The “piling on” problem

As a threshold matter, companies need to be prepared to face liability for the same offense in multiple jurisdictions. While the DOJ will continue to seek to coordinate resolutions, the absence of an internationally recognized principle of “double jeopardy” (non bis in idem) means that some countries can also bring separate “pile on” prosecutions against the same company or individual, for the same crime.

The Fifth Circuit has weighed in on the issue of whether a defendant can be successively prosecuted by two countries for the same crime, holding that “[d]ouble jeopardy does not attach when separate sovereigns prosecute the same offense.” In the 2010 case United States v. Jeong, which involved a Korean national prosecuted by both Korean and US authorities for bribes paid to US public officials for their assistance in obtaining a telecommunications contract, the Fifth Circuit found that the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions does not prohibit multiple prosecutions of the same defendant for the same offense, but only requires consultation under certain circumstances between countries with overlapping jurisdiction.

Although a number of applicable treaties and conventions in Europe do provide that individuals and entities cannot be prosecuted by different EU member states for the same criminal offense, recent developments underscore that these legal instruments do not provide absolute protection. For instance, in March 2018, France’s Court de Cassation determined that the principle of double jeopardy did not bar the prosecution in France of a company that had entered into a plea agreement with US authorities for the same underlying conduct.

As a matter of policy and practice, the DOJ’s FCPA Unit has sought to avoid unnecessary duplicate penalties imposed by separate sovereigns in FCPA cases through coordinated resolutions and the application of offsets and credits. For example, in December 2017, the DOJ announced that it would credit payments to Brazil and Singapore as part of its FCPA resolution with Keppel Offshore & Marine Ltd. In May 2018, this policy was formalized through revisions to the Justice Manual announced by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, with the new policy instructing DOJ components to coordinate with each other and with other enforcement authorities (including those outside the United States) to avoid the imposition of unnecessary duplicate fines, penalties, and/or forfeiture against a company. An interesting side effect of this coordination may be that US authorities increasingly receive a smaller “slice of the pie.”

Nevertheless, as the DOJ itself has acknowledged, coordination by the United States with its global partners will not resolve the “piling on” problem, as countries are not obligated to coordinate and can always try to seek additional resolutions. The December 2016 resolution with Odebrecht, the Brazilian conglomerate, for instance, involved coordination between US, Brazilian, and Swiss authorities — but since that resolution, the company has publicly entered into settlement agreements with several additional countries, including Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, Panama, and Peru.

As a practical matter, the absence of a universally recognized “international double jeopardy” principle and challenges in coordination mean that a company dealing with corruption allegations may still face separate enforcement actions in multiple jurisdictions based on the same conduct.

Voluntary disclosure considerations

The DOJ has consciously sought to provide incentives for companies to voluntarily self-disclose misconduct and cooperate, but companies considering whether to do so must now consider the repercussions of voluntary disclosure across multiple jurisdictions.

Following years of complaints about the opaque nature of the voluntary disclosure process, in November 2017, the DOJ announced a new FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy, which built on the prior FCPA Pilot Program to provide greater transparency about the tangible and quantifiable benefits of self-disclosure. Under the new policy, a company that voluntarily self-discloses, fully cooperates, and timely and appropriately remediates is entitled to a presumption that the DOJ will decline to prosecute the company absent certain aggravating circumstances. Even under circumstances where the DOJ determines that a criminal resolution is nonetheless appropriate, a company that self-discloses, cooperates, and remediates according to specified standards will still be eligible to receive a 50 percent reduction off the bottom end of the US Sentencing Guidelines fine range, whereas a company that cooperates and remediates but does not self-disclose will be eligible for a 25 percent reduction.

Authorities in a number of other jurisdictions have also sought to encourage voluntary disclosures by offering reduced financial penalties and negotiated resolutions such as deferred prosecution agreements (DPAs), which have recently been introduced in a number of new jurisdictions such as Singapore and France. In addition, enforcement authorities such as the UK’s SFO have published guidance regarding the self-reporting process and how self-reporting will be weighed when determining whether to prosecute a company.

Although never an easy decision to voluntarily subject your company to potential criminal liability, having certain assurances about — or at least a clearer understanding of — how disclosures will be handled, and the likely consequences, makes it easier for companies to perform the necessary risk-benefit analysis. But this calculus is necessarily muddied by the number of newly active enforcement authorities who may not only lack formal or even informal guidance on the benefits of disclosure, but may also have little or no track record from which insights could be gleaned.

Another issue affecting voluntary disclosure decisions stems from improved cross-border information sharing. In an era of multijurisdictional cooperation, companies must anticipate that a voluntary disclosure to an authority in one jurisdiction may create exposure in other jurisdictions. Even if a company is reasonably comfortable that one country’s enforcement authorities will have no interest in pursuing the case, there exists the possibility that the information could be shared with another country that might prosecute (or at least launch a more comprehensive investigation). Indeed, a number of companies have made the decision to self-report to their primary regulator but not alert the local authorities in another market (most often, the country where the bribery actually occurred) because the penalties were stricter or the enforcement less predictable.

There is also a real risk that foreign authorities may utilize investigative techniques prohibited under US law, or that internal communications and documents (including those related to a company’s internal investigation), which would be privileged in the United States, would be deemed non-privileged in other jurisdictions. Further complicating matters is the extraterritorial reach of most anti-corruption laws, meaning that a company is potentially subject to prosecution almost anywhere it maintains operations.

Finally, these information-sharing risks should be considered in light of the “piling on” issues discussed above. Even if a company has reasonable certainty about its potential exposure to US regulators under the FCPA, and even if the United States declines to pursue a case as a result of voluntary disclosure, cooperation, or other considerations, there remains a significant (and often unquantifiable) risk of additional penalties being imposed by a second sovereign. It is perhaps ironic that the United States has finally announced clear and tangible benefits for disclosure and cooperation even as it increasingly shares information with foreign states that neither have such guidelines nor offer any benefit for cooperation.

All of these issues underscore the fact that companies can no longer focus on potential outcomes with respect to their primary enforcement authority, but they must also consider the actions and reactions of other potentially interested enforcement authorities.

Lack of predictability and greater uncertainty

Another challenge, touched on above, is the unknown factor of many enforcement authorities. Only recently more engaged in enforcement, they may lack an established record of prior investigations and enforcement actions, which could be used to analyze how interactions with them might play out in the future. Their expectations during an investigation may differ from those of more familiar or established anti-corruption enforcement authorities, potentially driving up expenses and making it more difficult to resolve the matter.

They may also be seeking to enforce relatively new and untested anticorruption laws, including those with provisions requiring or awarding credit to companies that maintain effective compliance programs. In some instances, it may be unclear what these compliance program requirements mean in practice, and whether a company’s existing global compliance program will satisfy the new requirements. At a minimum, this lack of clarity will increase the time and expense needed to convince an enforcement authority that your program should qualify and you should receive credit for maintaining an effective compliance program. For instance, one jurisdiction’s new anti-corruption law requires certain companies to undertake corruption risk-mapping, and the newly created agency tasked with overseeing the law has released guidance in this regard. It remains to be seen, however, how the agency will enforce and interpret the risk mapping and other requirements in practice, and to what extent it will require multinational companies that already have robust compliance programs in place to adopt additional measures.

In addition, authorities in some jurisdictions may face external pressures that contribute to greater uncertainty, such as political pressures or scrutiny by multilateral organizations such as the OECD. These pressures could create incentives affecting the speed, scope, or overall approach of some high-profile investigations.

Companies must also proceed cautiously; keeping in mind the risks of interacting with unfamiliar and less predictable enforcement authorities, who may not always play by the rules. For instance, while some countries may have strict procedures and safeguards for maintaining the confidentiality of case-related information, other countries may not — as underscored by one recent matter in which sensitive investigation-related materials were leaked to the press in a foreign jurisdiction.

There are also matters in which individual enforcement authorities acted inconsistently with the laws they sought to uphold. In one country, a regulator threatened to bring trumped up corruption charges against the clients unless they agreed to a high value settlement. In another country, the representative of the enforcement authority tried to insert himself into a corrupt scheme, offering to serve as the intermediary in delivering the very bribe he was supposedly investigating in exchange for a kickback. While these represent extreme examples and are far from the norm, they reflect the real risks that may arise in an environment where companies are subject to unfamiliar enforcement authorities and jurisdictions. These considerations add a whole new layer to the already difficult question of whether or not to make a voluntary disclosure.

Variations in laws

While the core definition of corruption is effectively universal, there are nevertheless significant variations among the various anti-corruption laws that companies must take into account, particularly in light of the trend of multijurisdictional enforcement. For example, the FCPA famously does not reach private bribery and exempts facilitation payments, whereas the UK Bribery Act criminalizes both private bribery and facilitation payments. The result of variations like these is that multinational corporations are effectively forced to adopt compliance programs that accord with the strictest market in which they maintain a presence (both out of the need to maintain a single global policy and because the extraterritorial reach of most anticorruption laws effectively makes the strictest conditions apply universally).

Still, those sorts of legal distinctions can at least be reconciled. But what about other distinctions that may outright conflict with one another? For example, what if one country (which claims universal extraterritorial jurisdiction over all businesses operating within its borders) requires that any effective compliance program include comprehensive due diligence on all business partners. Meanwhile, another country (who also claims universal jurisdiction) states that due diligence should be performed only where it is consistent with its own data privacy laws. Plainly, it would be impossible for a company to comply fully with both edicts. One option would be to follow Country A’s laws for business partners in Country A and Country B’s laws for business partners in Country B, but that raises multiple issues. First, it greatly increases the complexity of your compliance program. Instead of having one standard for due diligence, you may now have dozens, which also require you to stay abreast of the latest developments in data privacy law. This, in turn, makes it harder to develop comprehensive metrics to quantify how your program is working — if you can’t compare apples to apples, it might be harder to identify regional trends or outliers. And, finally, it does not even completely insulate the company from liability; after all, both Country A and Country B may continue to assert jurisdiction over acts within the other’s borders.

Key practice pointers

In our view, the upsurge in global anti-corruption enforcement is significant not only for the headline grabbing value of the fines and penalties imposed as part of recent coordinated global resolutions but represents a fundamental change that compliance organizations must account for going forward.

- When considering whether to voluntarily disclose potential misconduct, the risks of disclosure to additional enforcement authorities must be carefully weighed. Consider including discussions with local counsel in all jurisdictions where you have potential exposure and limited insight into the expectations and behavior of local authorities. Companies that have an established disclosure protocol should also update it in light of these recent developments.

- To address legal conflicts and variations across jurisdictions, the best solution is almost always to find a way to settle on a single global standard while still addressing jurisdiction-specific issues. A disaggregated compliance program will rarely be as effective as a uniform one. Sometimes otherwise ethical companies are let down by a single geography where the rules go unheeded. Conduct an ongoing assessment as new laws hit the books and determine where your potential exposure is greatest. Ensure that it serves as a lodestar for structuring your compliance program. It’s not perfect, but we believe it is generally the best solution for a properly risk-based model.

- To mitigate the risks of operating in jurisdictions with less familiar or predictable enforcement authorities, make sure communications are handled by a trusted individual with knowledge of local enforcement practices (generally, this will be your local outside counsel). These individuals will be best equipped to identify and respond to intimidation tactics and to determine the enforcer’s true intentions. Second, ensure that any employees attending a meeting at an enforcement agency receives sufficient preparation in advance and that at least one other person is present who can alert the company if any issues arise (again, your local outside counsel is the most likely candidate for this role). Finally, it is critical your people know how to respond in the event of a dawn raid. Dawn raids can be used both for legitimate purposes and for intimidation purposes. You should anticipate a general increase in dawn raids as a result of expanded corruption enforcement efforts.

A new era of multijurisdictional enforcement

The uptick of multijurisdictional anti-corruption enforcement means that multinational companies now face both coordinated global resolutions involving record-setting fines and penalties and the prospect of “pile on” enforcement actions. Compliance organizations must carefully consider how to navigate this new era of multijurisdictional enforcement. As jurisdictions continue to adopt new anticorruption laws and devote significant resources to prosecuting corruption, it is clear that the challenges of designing and implementing an effective global compliance program in this enforcement environment will remain — and continue to evolve.

Further Reading

In 2009, Kellogg Brown & Root LLC agreed to pay a US$402 million criminal fine and its parent company KBR Inc. and its former parent company Halliburton Company jointly agreed to pay US$177 million in disgorgement, related to its involvement in the four company joint venture TSKJ. Between 2009-2011, each of the four members of the TSKJ joint venture was subject to separate enforcement actions totaling over US$1.5 billion.

The fines levied against GSK by Chinese and US authorities were not coordinated. Chinese authorities fined GSK US$489 million in 2014, while the SEC imposed a US$20 million penalty on the company in 2016.

Daniel Kahn, Responding to the Upward Trend of Multijurisdictional Cases: Problems and Solutions, 66 DOJ J. FED. L. & PRAC. 125, 126, no. 5, 2018.

The Second Circuit’s recent decision in United States v. Hoskins, No. 16-1010, -- F.3d --, 2018 WL 4038192 (2d Cir. Aug. 24, 2018), is illustrative. The Court limited the reach of the FCPA by holding that foreign nationals who cannot be charged as principals under the FCPA also cannot be held liable for conspiring to violate or aiding and abetting a violation of the statute — in other words, conspiracy and complicity charges cannot be used to extend liability beyond the FCPA’s specifically enumerated categories of defendants.

Daniel Kahn, Responding to the Upward Trend of Multijurisdictional Cases: Problems and Solutions, 66 DOJ J. FED. L. & PRAC. 125, 126, no. 5, 2018

Austin Ramzy, Najib Razak, Former Malaysian Prime Minister, to Face More Charges, N.Y. TIMES, Sept. 19, 2018.

JUSTICE MANUAL § 1-12.100.

Sandra Moser's remarks at the ACI's 8th Global Forum on Anti-Corruption in High Risk Markets

Daniel Kahn, Responding to the Upward Trend of Multijurisdictional Cases: Problems and Solutions, 66 DOJ J. FED. L. & PRAC. 125, 131, no. 5, 2018 (describing use of compelled testimony by criminal authorities in certain jurisdictions even where the witness is not granted full immunity).