CHEAT SHEET

- AML rules globally. Anti-money laundering (AML) rules are globally ubiquitous and affect businesses in over 200 countries, but the requirements differ in every country.

- Outcomes science. Outcomes science is concerned only with the results — whether the rules work.

- Interception rate. The interception rate of criminal funds confiscated is a useful proxy indicator in determining the effectiveness of regulations intended to disrupt serious profit-motivated crime.

- In-house role. In-house counsel can interpret AML regulations and help guide company conversations with regulators and politicians about regulatory frameworks.

In November 2017, the US Senate testimony of a former US intelligence officer and Treasury special agent, later repeated in Politico in relation to Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation, opened with a quote from Dr. Ron Pol describing anti-money laundering rules as arguably “the least effective of any anti-crime measure, anywhere.” The quote came from a New Zealand newspaper report two years earlier, when the country was considering extending anti-money laundering obligations to lawyers and other professionals, the subject of Dr. Pol’s PhD thesis.

The ACC Docket asked Dr. Pol to outline the results of his research, which offers fresh insights into an area directly or indirectly affecting the way in-house counsel operate worldwide, including ACC members. As the former head of New Zealand’s corporate lawyers’ association, Dr. Pol is well placed to explain its significance for in-house counsel. He has also has presented at ACC annual meetings, authored long-running Docket columns, and is a member of the Docket’s editorial advisory board.

Docket: To help orient readers in the broader context before discussing implications for in-house counsel, can you give us a brief overview of some of the broader issues that prompted the research?

Pol: Despite the huge global reach of extensive anti-money laundering (AML) regulations, there is surprisingly little discussion in AML practice about effectiveness. There are constant calls to extend regulatory scope, but the obvious question — to what extent AML rules work — is notable both for its absence and unsubstantiated assertions about effectiveness.

Moreover, getting a clear view of the effectiveness of a vast global network of AML regulations is clouded by a mass of contradictions. For example, the industry has been extraordinarily successful, yet spectacularly ineffective.

An expansive and costly regulatory framework to deal with the perceived threat of money laundering is globally ubiquitous yet seems to have had barely any material impact on serious profit-motivated crime.

The astonishing success of the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in extending anti-money laundering rules globally itself represents a barrier to better outcomes.

Illicit funds disruption scarcely has the impact of a rounding error in the accounts of “Criminals, Inc.” This suggests that modern AML rules are almost completely ineffective in disrupting the proceeds and funding of serious crime.

In a self-generated atmosphere of consensus, officials drawn into transnational networks and socialised in the anti-money laundering lexicon, formal rating systems, and a self-generated success narrative seldom acknowledge, let alone address, uncomfortable truths about the gap between intention and results.

Curiously, private sector actors, such as banks forced to implement AML compliance systems including elements that they know are poorly connected with fundamental risk, have inadvertently helped expand the regulatory burden on themselves.

Independent, uncoordinated actions of private actors, such as banks and insurance companies using industry ratings as a proxy for underlying risk in their dealings with overseas financial institutions, effectively compelled more countries to “sign up” for the burgeoning AML complex. And “staying on-side with regulators” meant that banks didn’t always share reservations about poorly designed systems, thereby inadvertently enabling a continual stream of extensions despite poor results.

But, whatever the reasons, the serious gap between intention and results is clear and troubling. A disturbing feature of the modern “coercive voluntary” AML regime is that countries don’t necessarily implement or extend AML systems for the ostensible (crime prevention) objectives. University of Cambridge Professor Jason Sharman once remarked that countries facing higher costs or potential difficulties accessing financial markets adopted money laundering controls as a “functionally useless but symbolically useful measure to reassure outsiders.”

Governments exposed to AML evaluations are also hesitant to adopt policies that might lead to poor ratings or restrict access to financial markets. When “getting the FATF tick” becomes the primary policy objective, improving the capacity to detect and prevent serious crime is relegated to a rhetorical device; invariably asserted, but seldom guiding the regulations. This is consistent with research results.

Docket: The research, published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, combines money laundering research with outcomes science. What do you mean by that?

Pol: Outcomes science, or in political-science-speak policy effectiveness, is concerned not just whether rules exist, or meet specified standards, or if countries implement them, or even if firms comply with the regulations (each of which is typically a compliance focus), but whether the rules work. Do they produce intended outcomes?

Docket: What did the research find?

Pol: Illicit funds disruption scarcely has the impact of a rounding error in the accounts of “Criminals, Inc.” This suggests that modern AML rules are almost completely ineffective in disrupting the proceeds and funding of serious crime. Authorities rightly claim success when suspicious activity reports lead to more arrests and seizures of criminal assets, and the impact on criminal enterprises identified by money laundering controls is, of course, profound, but a routine focus on output measures like arrests and forfeitures obscures higher-order crime prevention outcomes.

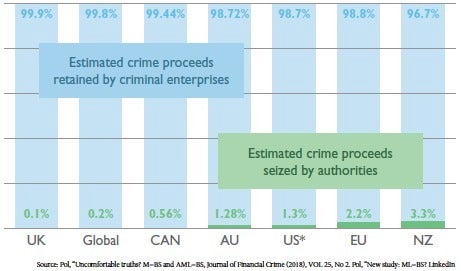

No material differences were found associated with professionals’ inclusion or exclusion from money laundering regulations. In fact, there was little difference between countries generally. The rate of criminal funds intercepted was uniformly trivial, from 0.1 to 3.3 percent.

Docket: It must be difficult to measure true outcome measures, such as less social and economic harms from cutting profit-motivated crime, so what metric did you use?

Pol: Drawing from countries’ own proceeds of crime estimates and policing data, I calculated what the United Nations calls the “success rate” of money laundering controls. The “interception rate” of criminal funds confiscated is a useful proxy indicator toward outcomes because it helps assess the effectiveness of regulations intended to disrupt serious profit-motivated crime like drugs-, arms-, and human-trafficking, high-level corruption, fraud, and tax evasion.

Docket: To justify regulatory expansion, authorities and their advisers often claim that “closing loopholes” — such as ending lawyers’ exclusion from money laundering controls in the United States — will have a big crime prevention impact. How did you test for this?

Pol: The research sampled countries with full money laundering controls on banks but with different rules for professional facilitators like lawyers, accountants, and realtors. The AML industry is constantly seeking to extend its reach, based on the premise that as more businesses are required to vet their customers and clients, examine the source of funds, and report suspicious transactions to authorities, it will improve the capacity to detect, disrupt, and prevent serious profit-motivated crime. It sounds like a reasonable assumption but, surprisingly, it remains mostly a tenet of faith, seldom tested.

If those claims are correct, that is, if extending anti-money laundering regulations to lawyers and other professionals really does markedly improve the ability to intercept criminal finances, it should be possible to detect differences between countries with money laundering controls over some (Canada), none (Australia), or all (United Kingdom) such professions, and where they have limited obligations (New Zealand).

Docket: Did the research validate the “closing loopholes” claims?

Pol: No material differences were found associated with professionals’ inclusion or exclusion from money laundering regulations. In fact, there was little difference between countries generally. The rate of criminal funds intercepted was uniformly trivial, from 0.1 to 3.3 percent. And the highest rate, in New Zealand, was based on official data that excluded important areas of crime generating illicit funds, so its “real” interception rate will be lower. Broadly speaking at around or typically less than one percent, it seems that countries effectively “tax” organized crime groups a tiny fraction of their illicit earnings. Despite the fact that “making crime not pay” rhetoric is nearly as ubiquitous as money laundering controls, it seems that serious profit-motivated crime pays seriously well.

Docket: Were the findings a surprise?

Pol: The new research extended findings from earlier studies by the United Nations (assisted by the US State Department) and Europol, Europe’s law enforcement agency. The UN found that authorities globally disrupt just 0.2 percent of criminal funds each year. Europe fares better, but still just 1.1 percent is confiscated. Europol admits that amounts recovered are a tiny fraction of crime proceeds, with 98.9 percent of estimated criminal profits remaining in organized crime network coffers.

So, the findings weren’t particularly startling, because they accorded with studies by the United Nations and Europol. More surprising, however, is that the industry’s open secret about its lack of effectiveness continues, seldom addressed and unresolved, despite a steady stream of evidence illustrating a huge gap between well-meaning intentions and the uncomfortable reality of results. With one notable exception (a new “effectiveness” assessment methodology, addressed in a separate study that found it was incapable of assessing effectiveness as it intended) the industry narrative continues to call for “more of the same,” with new “solutions” regularly touted to support regulatory expansion; a constant refrain since 1990.

Docket: In-house counsel are not typically subject to AML obligations, so, presumably, the relevance of the regulations relates to the impact on their employers’ businesses?

Pol: Absolutely, that’s an important element. AML rules are globally ubiquitous. They affect millions of businesses in over 200 countries. But the requirements and detailed obligations are different in every one of those countries, so corporate counsel are frequently asked to interpret the regulations, and to support their compliance, risk, ethics, and corporate governance colleagues.

Docket: Your research isn’t about specific regulations, so how can in-house counsel use it to add strategic value?

Pol: In-house counsel often engage directly with policymakers, regulators, and enforcement agencies, so it’s important that they understand the rationale, underlying policy intentions, and shortcomings of the regime. International standards also require external lawyers to be subject to AML obligations, and to report “suspicious” transactions, a deeply contentious proposition in the profession. The in-house experience, particularly from companies with AML obligations, offers a valuable perspective across the wider legal profession.

Docket: In what other ways can in-house counsel add value?

Pol: Unlike other professions from which it draws (including law, accounting, and law enforcement, which have had centuries to test and refine underpinning assumptions), the AML industry is only a few decades old. As a result, much of it still operates on assumptions and beliefs about what works. Professional development and training programs are also typically aimed at meeting specific compliance requirements, and seldom invite participants to test core assumptions underpinning the industry.

At law school, however, we’re trained to critically examine assertions. So, although corporate counsel obviously add value at a technical level by interpreting regulations, lawyers’ capacity, training, and inclination to test assumptions also makes in-house counsel uniquely placed to add value in other areas as well. Not just to help compliance staff meet technical requirements, but to help guide companies’ conversations with regulators and politicians about regulatory frameworks that might better help achieve intended outcomes. And perhaps reduce some of the compliance burden by helping eliminate some of the rules that detract from better outcomes.

More surprising, however, is that the industry’s open secret about its lack of effectiveness continues, seldom addressed and unresolved, despite a steady stream of evidence illustrating a huge gap between well-meaning intentions and the uncomfortable reality of results.

Docket: What’s your own objective for this research?

Pol: My goal is simple. To see if it’s possible to cut through the “noise” and find new ways to potentially help make a significant, demonstrable impact on serious profit-motivated crime. And substantially reduce the immense social and economic harms caused by drugs-, arms- and human-trafficking, sex and labor exploitation, fraud, corruption, tax evasion, and countless other serious profit-motivated crimes.

Since Nixon, various “wars” on drugs haven’t worked. Since 1990, the G7 nations established the FATF to sever the financing from serious crime. Millions of businesses now spend billions of dollars each year to comply with rules based on standards. Trouble is, the “fight” against money laundering hasn’t worked either.

Much like the previous “wars,” the “body count” is prodigious. Likewise, the political rhetoric. Every few days somewhere in the world a politician or law enforcement chief is photographed amongst piles of seized drugs and cash, “proving” success in the “war” on money laundering, claiming that “crime doesn’t pay.”

Each arrest, and every seizure is, of course, a legitimate success metric too. Many criminals have been arrested, criminal enterprises dismantled, and illicit assets seized (some triggered by money laundering controls, many others by traditional policing), but often with little discernible impact on crime. There have been many successes, but no (overall) success.

Docket: What final lessons might in-house counsel take from the research?

Pol: Corporate counsel are uniquely placed to spark meaningful conversations about regulatory effectiveness. Businesses often want to help prevent serious crime, not endlessly expand departments that can prove “compliance” but without much impact on crime. With deep knowledge about regulations that work, and their own businesses, in-house counsel can help firms reduce the destructive effects of serious profit-motivated crime, with less regulatory clutter. After all, that’s what the anti-money laundering industry, and governments, presumably also want to achieve — better outcomes.

The research

“Uncomfortable truths? ML=BS and AML=BS2” Journal of Financial Crime, 2018, Vol 25, No. 2.

“Anti-money laundering effectiveness: Assessing outcomes or ticking boxes?” Journal of Money Laundering Control, 2018, Vol 21, No. 2. Depending on your company’s access to scientific publications, a charge may apply for these articles. The author receives no part of any such charge.

A free outline is available in several articles on the author’s LinkedIn account: “New study: ML=BS?” and “Laundry-wash: FATF ratings clean the toughest stains.”

Dr. Ron Pol is the former leader of New Zealand’s corporate lawyers’ association and a member of the ACC Docket’s advisory board.