CHEAT SHEET

- Transfer restrictions. Many countries in Asia restrict cross-border transfers of personal information overseas unless the recipient is in a whitelisted country recognized by data protection authorities and has a contract and/or consent from the data subjects.

- Accountability agents. TRUSTe and the Japan Institute for Promotion of Digital Economy and Community are the two accountability agents recognized by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. An organization must submit its privacy policies to them to be certified as compliant with the Cross Border Privacy Rules.

- Data localization. China, Indonesia, Vietnam, South Korea, and Malaysia require certain data to be stored within a country’s own borders.

- DPO. Privacy laws in Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, Singapore, and the Philippines require a Data Protection Officer, like GDPR does.

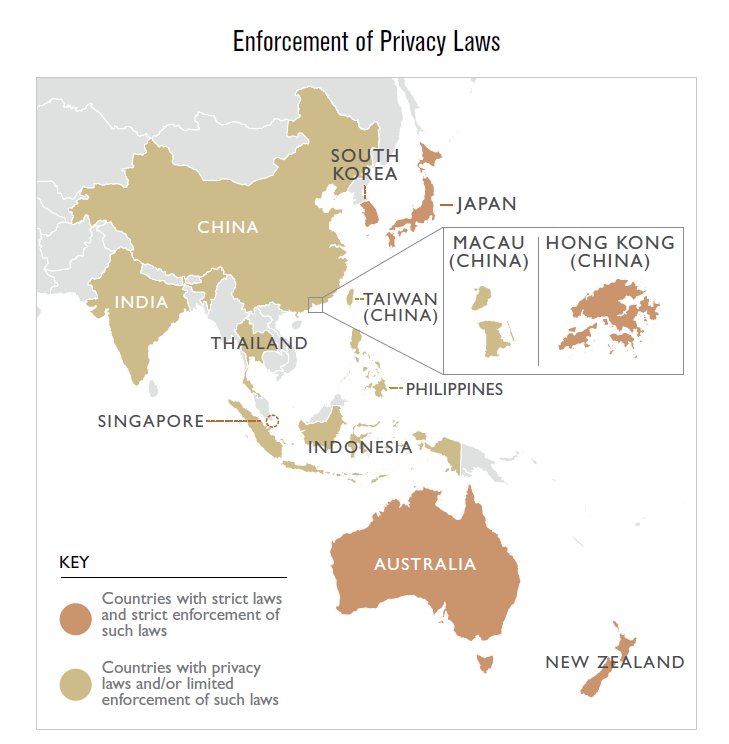

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into effect in May 2018, is widely considered the most comprehensive data protection law in the world. Many businesses treat GDPR as an international standard, and assume that as long as they comply with it, they will satisfy all other international requirements as well. While it is generally true that GDPR constitutes the most wide-ranging data handling regulation to date, it does not necessarily set the highest bar in all areas. In particular, Asia’s data protection policies differ from GDPR in a few key areas. A business that fails to account for these differences may fully comply with GDPR and still run afoul of Asia’s laws, subjecting itself to the possibility of fines, penalties, or other legal actions.

Multinational conglomerates, including Apple and Cisco, have chosen to voluntarily certify with the Cross Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) system to transfer personal data among Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) economies.

International data transfers

Under GDPR, the transfer of data between international jurisdictions that are not in the European Economic Area, or not deemed to have an adequate level of protection, trigger certain requirements such as using model contract clauses, binding corporate rules, an approved code of conduct, or other approved mechanisms pursuant to GDPR. Many countries in the Asia-Pacific region, including Australia, India, Malaysia, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, and South Korea, also restrict cross-border transfers of personal information overseas, unless the recipient is located in a country providing adequate protection of the personal information.

“Adequate protection” usually means the overseas recipient is located in a “whitelisted” country recognized by the data protection authorities (DPAs) and a contract with the recipient and/or consent from the data subjects is required to transfer personal data outside the country. For example, the Australia Privacy Principles (APP) require entities disclosing personal data of Australians to take “reasonable steps” to ensure adequate protection, which usually means obtaining an enforceable contractual commitment from the overseas recipient that it will handle personal information in accordance with the APP.

Singapore takes a similar approach, and prohibits any data transfer outside Singapore, unless an organization has taken appropriate steps to ensure that recipient will be bound by legally enforceable obligations to protect the personal data under standards comparable to the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA). Such legally enforceable obligations would include any applicable laws of the country to which the personal data is transferred, contractual obligations, or binding corporate rules for intra-company transfers.

It is worth noting that most of the DPAs in the Asia-Pacific region have not yet issued a list of the “whitelisted” countries that they believe provide adequate protection. As a result, organizations operating in these countries are left to assume that all countries are deemed to be inadequate and must put in place approved mechanisms to satisfy the rules.

Multinational conglomerates, including Apple and Cisco, have chosen to voluntarily certify with the Cross Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) system to transfer personal data among Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) economies. There are currently eight participating APEC economies: the United States, Mexico, Japan, Canada, Singapore, South Korea, Australia, and Taiwan. To obtain a certification from the CBPR, organizations must develop their own privacy policies governing their cross-border data transfer practices and submit their privacy policies for evaluation by an APEC-recognized accountability agent. Their internal privacy policies must meet or exceed the standards under the APEC Privacy Framework.

Two institutions are recognized as a qualified accountability agent: TRUSTe and the Japan Institute for Promotion of Digital Economy and Community (JIPDEC). If an accountability agent determines that an organization is in compliance, that enterprise will be certified as CBPR-compliant and identified on the CBPR website. As of March 4, 2019, there were 26 organizations listed as APEC CBPR certified.

Data storage and localization requirements

A recent trend is emerging where some countries are requiring certain data to be stored within a country’s own borders. GDPR does not have any data storage or localization requirements, but several Asian countries do. These countries include China, Indonesia, Vietnam, South Korea, and Malaysia. Data localization rules pose specific challenges for companies operating in these jurisdictions.

For example, the newly passed Chinese Cybersecurity Law requires “critical and personal information” collected from China “in critical industries” to be stored within the territory of China. Although China has not yet provided guidance on the data localization requirement, companies have interpreted it to essentially require an entity to hold an updated copy of each Chinese citizen’s personal data in China. Additionally, China also requires localization of data servers by any insurance institution processing the personal data of Chinese citizens.

Similarly, Indonesia’s draft regulation for internet audio, video, or other media service providers requires an offshore entity to have a physical presence in Indonesia. Further, Indonesia requires electronic system operators that provide public services to have data centers and disaster recovery centers in Indonesia as part of a business continuity plan. South Korea does not have broad data localization requirements, but it requires specific data to stay within its borders. For example, local mapping data is restricted from being exported to foreign companies that do not operate domestic data servers.

Companies operating in these countries should remain aware of applicable data localization laws to assess the potential impact on their businesses. One practical solution to comply with these data localization rules is to host at least one data center in the local country, storing restricted personal data in local data centers. Another solution is to make arrangements with cloud service providers to store data locally.

In China, multinational technology giants such as AirBnB, Uber, Evernote, LinkedIn, Amazon, and Apple have started storing data for its Chinese users on domestic Chinese servers well before the official implementation of the Chinese Cybersecurity Law. Compared to storing data in cloud-based offshore platforms, this solution comes wit substantial increased costs, including expenses associated with setting up a local infrastructure and hiring employees. Obviously, these expenses must be taken into consideration when designing a compliance strategy.

Review of sectorial laws

One of the key benefits of the GDPR is that, for the most part, it harmonizes and standardizes data protection laws across the European Union. There are a few key areas in which member states depart from GDPR to adopt their own national laws (i.e., privacy issues related to employment law). Most Asian countries do not have an all-encompassing law that covers nearly all sectors of the economy. Thus, reviewing sector-specific laws in each country, depending on the types of data processed, is a must.

For example, in Australia, in addition to the APP, specific state and federal acts will apply depending on the types of information processed (such as credit information, tax file numbers, healthcare identifiers, or health records) and types of activities an organization is engaged in (e.g., communicating over telecommunication networks). India has different regulations governing the collection, use, and disclosure of financial records, children’s information, and biometric information. In South Korea, in addition to the Korean Data Protection Act (which serves as the umbrella privacy law in South Korea), various subject-specific laws regulate privacy and cybersecurity in their respective sectors. These laws include the Act on the Promotion of IT Network Use and Information Protection, the Use and Protection of Credit Information Act, the Electronic Financial Transactions Act, and the Use and Protection of Location Information Act.

Case study: How to comply with Article 37 of the Chinese Cybersecurity Law

Companies attempting to comply with Article 37 of the Chinese Cybersecurity Law may choose between setting up a data center in China or making arrangements with cloud providers that are able to retain data in China. A Chinese legal entity is usually required to take advantage of either option. For example, some companies have chosen to establish wholly-foreign owned enterprises (WFOEs) or joint ventures with Chinese partners to make arrangements with Amazon to use its Chinese-specific cloud products, in compliance with the data localization requirements

For multinational companies, it is essential to identify the applicable local laws and regulations to ensure compliance with all laws and regulations in the Asia-Pacific region.

DPO requirements

According to Article 37 of GDPR, public authorities, as well as entities whose core activities involve “regular and systematic monitoring of data subjects on a large scale,” or that control or process special categories of personal data, must designate a Data Protection Officer (DPO). Certain Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, Singapore, and the Philippines also require a DPO. For example, Section 11 of Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) requires that an entity hire an individual or service provider that is responsible for ensuring that the entity complies with the PDPA.

In addition, it is also important to remember that a DPO under the GDPR may have different responsibilities or obligations than a DPO working under a country-specific act.

Proceed with care

For many organizations with a global footprint, compliance with GDPR does not guarantee a free pass in the Asia-Pacific region. As a starting point, organizations might consider taking the following actions:

- Data mapping and inventory activities. Organizations should conduct data mapping and inventory exercises to better understand the categories, quantity, and location of personal data they collect from the Asia-Pacific region.

- Determine the applicable laws for specific sectors. For multinational companies, it is essential to identify the applicable local laws and regulations to ensure compliance with all laws and regulations in the Asia-Pacific region. A compliance officer may consider the following factors when identifying all applicable laws: What are the specific types of personal data collected? What are the processing activities? Who, and from where, is the organization collecting personal data?

- Implement mechanisms to enable cross-border data transfers. For organizations needing to move personal data out of a country with restrictions on cross-border data transfers, implementing an appropriate mechanism to legalize such international data flow is a must.

- Evaluate costs and risks for keeping data locally. For companies operating in countries with data localization requirements, it is important to keep in mind the increased costs of, and expenses incurred, in storing data locally.