CHEAT SHEET

- Job description. After corporate scandals like Enron and the 2008 Financial Crisis, a corporate secretary changed from an administrative assistant to a board advisor and point of contact for shareholders.

- Know-it-all. A corporate secretary should possess at least a basic knowledge of corporate and security laws, thorough understanding of the company’s business, good communication and diplomacy, and have a creative, detail-oriented personality.

- What’s in a name? The corporate secretary role (also known as company secretary or board secretary) is increasingly being referred to as chief governance officer to convey the senior status of the position and high level of sophistication required.

- Splitting tasks. While a single person can perform both the functions of corporate secretary and general counsel, it may be ideal for both roles to be undertaken by two different people.

As with many things in our legal world, the answer here is both simple and frustrating: It depends. Many factors come into play. It may depend on the company profile — its size, business area, level of regulation, governance structure and priorities, budget, management practices, and so on. It also depends on the individual professional perspective — duties, skills, professional and educational background, career aspirations, and talent.

The number one skill that is a must for every corporate secretary is to possess at least a basic knowledge of corporate and securities laws that affect the company in its principal place of business, or headquarters.

Defining the corporate secretary role

The corporate secretary role has evolved significantly in the past few years.

In the US financial market, the enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) were not only regulatory responses to the major corporate and accounting scandals (Enron and WorldCom) and the financial crisis of 2007–2008, but also the watershed moment for the corporate secretary profession.1 Before those regulations, a corporate secretary was the person responsible for recording meetings,2 akin to an administrative assistant or a simple record keeper. After the Enron scandal, the corporate secretary gained new responsibilities, far deeper than a simple record keeper.3 It became one of the most important board advisors and one of the primary contact persons for shareholders, to the point that a change was warranted.

The corporate secretary role has different titles in different jurisdictions. In the United States, the most common denomination is “corporate secretary,” while in the United Kingdom, the role is generally referred to as “company secretary.” Some countries also use “board secretary.”4 Regardless of the title, this role is increasingly recognized as one that requires a high level of sophistication.

The title of “chief governance officer” is becoming more accepted, as it clearly conveys that the position is at a senior officer level (sometimes even appointed by the board and not by the chief executive officer), and at the same time, the title clarifies that the person is in charge of providing advice and supporting the board. Another advantage of using this new title is avoiding confusion with the ordinary secretary function — more often referred to as administrative assistant today (i.e., a more clerical, administrative role).

Historically, the corporate secretary role was limited to clerical tasks (e.g., drafting minutes, checking paperwork, and minding formal filing requirements). In today’s more complex and sophisticated business world, the role is expanding, and chief governance officer seems to be a more accurate title. Nevertheless, the corporate secretary denomination will be used in this article because it is more familiar.

How to become a corporate secretary

A corporate secretary position within a US company is responsible for properly keeping the corporation’s business records — especially the minutes of the proceedings pertaining to the meetings of shareholders, the board, and its committees. Although the position is not a legal requirement itself,5 the record-keeping duty is described at the US state level,6 for instance, in Delaware,7 California,8 and New York.9 At the US national level, the same duty can be noted in the financial market regulation, such as the Exchange Act.10 Even if there are not more detailed statutory requirements, as a matter of good governance practice, the following lists of skills and duties are associated with the position of corporate secretary in today’s job market.

Corporate secretary skills

The number one skill that is a must for every corporate secretary is to possess at least a basic knowledge of corporate and securities laws that affect the company in its principal place of business, or headquarters. When a company has multiple subsidiaries in different countries, it might be difficult to know everything. Consulting local legal advisors, especially if the board is composed of members from disparate jurisdictions, or holding some of the meetings in those various locations, can rectify the problem. The depth of knowledge gained by having a diverse board or places of meetings can justify this measure.

The second most sought-after skill for a corporate secretary is a thorough understanding of the company’s business. Of course, this skill is normally mastered after the corporate secretary begins the job. A good professional will make this a priority once they join the business. A degree in business administration or commerce, law, and/or accounting is very helpful and sometimes essential. Corporate secretaries are expected to keep the board aware of current changes in relevant areas.

The third most sought-after skill for a corporate secretary is diplomacy, sometimes referred to as “executive presence.”

The third most sought-after skill for a corporate secretary is diplomacy, sometimes referred to as “executive presence.” Ideally, the corporate secretary is the “go-to” person in charge of answering the board’s questions. In other words, the person keeps an intuitive and sensitive presence, aware of the thoughts and feelings of the main stakeholders, including the board of directors, the CEO and — at the same level of care — the general counsel. The main goal should always be to achieve consensus within multidisciplinary settings and to navigate around bureaucratic thinking. Considering that the corporate secretary is usually the person responsible for keeping board portals, they need to know how to organize the information, distribute it, store it safely, and ensure the data is easily accessible. Finally, a good corporate secretary should have a flexible, creative, and detail-oriented personality. In practice, that means they must know how to remain calm no matter how difficult and pressured the working environment becomes.

Corporate secretary duties

The corporate secretary’s duties can be divided into two categories: ordinary and evolved.

The ordinary duties of a corporate secretary

The first group consists of the basic responsibilities,11 which are meeting preparation, agenda planning, records storage, and minute-taking — the hallmark of the corporate secretary role.12 Special thought should be given to this traditional responsibility, which impacts certain types of litigation, such as the shareholder derivative lawsuits. US caselaw helped delineate guidelines defining the minute-taking practice, and the legal consequences of poor performance.

The Walt Disney case is commonly cited as a classic warning of an outcome of poor minute-taking.13 Considered the leading case on executive compensation, and commonly called the corporate governance “case of the century,” this shareholder derivative lawsuit was brought in connection with Walt Disney Company’s hiring and subsequent termination of Michael Ovitz as executive president and director. Ovitz, the founder of Creative Artists Agency (a top Hollywood talent finder), had an income of US$20 million before joining Disney in 1995 for about US$24 million per year. After one year, Ovitz’s contract was terminated, and he walked away with US$140 million for a year’s work.

Shareholders brought a derivative suit, alleging, among other charges, that the compensation committee “inadequately investigated the proposed term” of the Ovitz employment agreement, and pointed to the fact that the compensation committee spent more time discussing additional compensation for the chair of the compensation committee handling the negotiations than on the terms of the agreement. Plaintiffs used the sparse minutes of the committee meeting to attack Disney’s hiring and firing of Ovitz because the minutes do not recount any discussion of how Ovitz could receive a non-fault termination.

In the end, Delaware’s Supreme Court upheld the Chancellor’s determination that the compensation committee members did not breach their fiduciary duty of care in approving the Ovitz employment agreement. The court found that “the documentation is far less than what best practices would have dictated,” and that “[t]here is no exhibit to the minutes that discloses, in a single document, the estimated value of the accelerated options in the event of a [non-fault] termination after one year.” The court pointed out that “[t]he information imparted to the committee members on that subject is, however, supported by other evidence, most notably the trial testimony of various witnesses about spreadsheets that were prepared for the compensation committee meetings,” and concluded that “[i]t is on this record that the Chancellor found that the compensation committee was informed of the material facts relating to [a non-fault termination] payout,” although the court also noted that “[i]f measured in terms of the documentation that would have been generated if ‘best practices’ had been followed, that record leaves much to be desired.”14 Although the company eventually won the case, it is fair to assume that if the board minutes had been better drafted, the company would not have had to spend about 10 years in court, incurring presumably substantial legal fees.

The Netsmart shareholders litigation is a better example of the undesired consequences of bad minute-taking.15 Due to the practically non-existent board minutes,16 the defendant company had to withdraw from a merger operation and cover the legal fees of the shareholders’ counsel in the sum of US$530,000 “to eliminate the burden, expense, inconvenience and distraction of continued litigation over plaintiffs’ claim for attorneys’ fees and expenses.”17

Thus, drafting minutes should be regarded not only as an important task, but also as an art. Like any artist, practice is essential to achieving perfection (or something very close to it). A competent corporate secretary will understand not merely the formal aspects (such as document dating, quorum noting, signatures collection, and document storage), but also the substantial aspects of the minutes, including the purposes the record will serve, when different drafting styles are required, who will access the documents, and — most importantly — against whom they might be used.18

The minutes’ purpose is simple: They are a way to keep track of the context of the decision-making process.19 In fact, nothing is more efficient and effective than a well-drafted minute to fulfill the fiduciary duties of loyalty and care that every prudent board must observe.20 Like well-written stories that are able to transmit a uniform message to any reader, regardless of life experience, background knowledge, and personality type, a well-drafted minute should give room to as few different interpretations as possible. A good drafter has to portray, in the clearest manner possible, an act of wisdom and good faith that was taken in the best interest of the corporation and free of any potential conflict of interest between the act and the board members.

Basically, the minute-taker faces two approaches when drafting documents: the detailed style and the summarized style.21

The detailed style requires less artful writing as it focuses on a lengthier — and thus not so filtered — registering of information. This approach is beneficial for situations that necessitate good public relations and require ultimate transparency for the benefit of all stakeholders. It is very helpful in terms of recovering past memories of the discussions behind the decision-making process, which may be very interesting for new board members familiarizing themselves with the business, and to acquaint themselves with previous business strategies. Lengthy minutes should be very useful when taken as evidence to the courts, especially to help the company lawyers defend decisions taken under the business judgment rule.

On the other hand, the detailed style might be quite time-consuming, both from the drafter’s and the board’s perspective. Lengthy drafts could demand more time to write (which might be a problem for a general counsel wearing the two hats)22 and to review. It is also true that information in excess may cause more confusion from the reader’s standpoint, especially for stakeholders who are not familiar with the intricacies of business governance in general. Detailed minutes may also backfire if used as evidence in disputes regarding the business judgment rule, and could also bring some bad publicity to the company, especially if something harsh or inadequate is said and duly recorded in writing, even without intending to offend anyone.

By contrast, the summarized style may be useful to speed-up board dynamics, especially the draft-reviewing process, which could be essential for very busy directors. The objective is to only focus on the essentials, something that’s easier to achieve when the corporate secretary is also the general counsel. Noting only essential information may be more helpful (and less confusing) to shareholders and other stakeholders not familiar with the business world.

However, shorter minutes provide less accuracy to retrace discussions behind decisions, which might make the memory recalling process more time-consuming and, therefore, jeopardize the time saved during the drafting and reviewing. In the end, however, the board chair’s personal preferences will play a significant role when choosing which writing style should be used by the corporate secretary.23

The evolved duties of a corporate secretary

The second group of duties differs, depending on the type of business entity. The corporate secretary can be required to ensure the business is conducted according to the internal rules of the company, i.e., the bylaws, code of ethics, policies, and so forth.24 Only being aware of the existing laws, however, is not good enough. The corporate secretary must understand, comprehend, and be able to translate legal rules into non-legal language, so the board and the top managers are on the same page.

Only being aware of the existing laws, however, is not good enough. The corporate secretary must understand, comprehend, and be able to translate legal rules into non-legal language, so the board and the top managers are on the same page.

Last but not the least, the corporate secretary is required to act as a “drawbridge” or a “conduit” between the company’s top management (the board and the chief executive officer) and the shareholders (either directly or through proxy firms).25 This responsibility can vary from being a liaison or communications facilitator to someone proactively carrying the burden of the oversight of dividends payments, share allotments, certificates, and/or transfers.26

When figuring out such issues, one can easily understand why lawyers are the most sought after professionals for drafting such documents. It is a fair and common assumption because an attorney has learned the habits to avoid or lessen future dangers.27

Wearing two hats: A matter of convenience or corporate strategy?

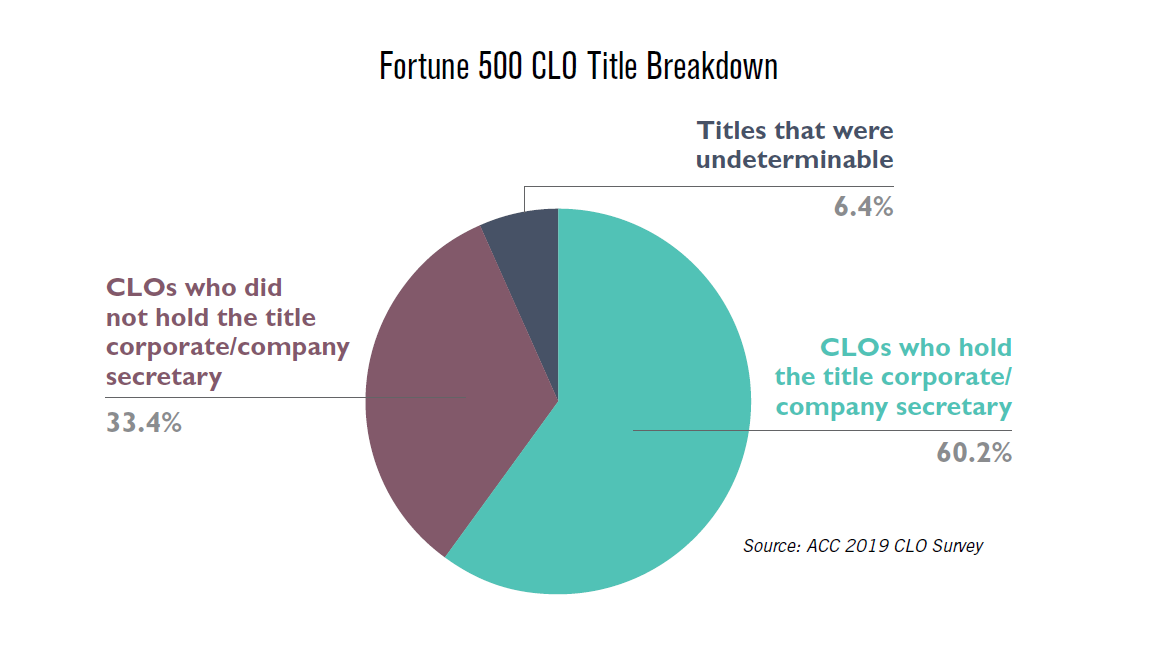

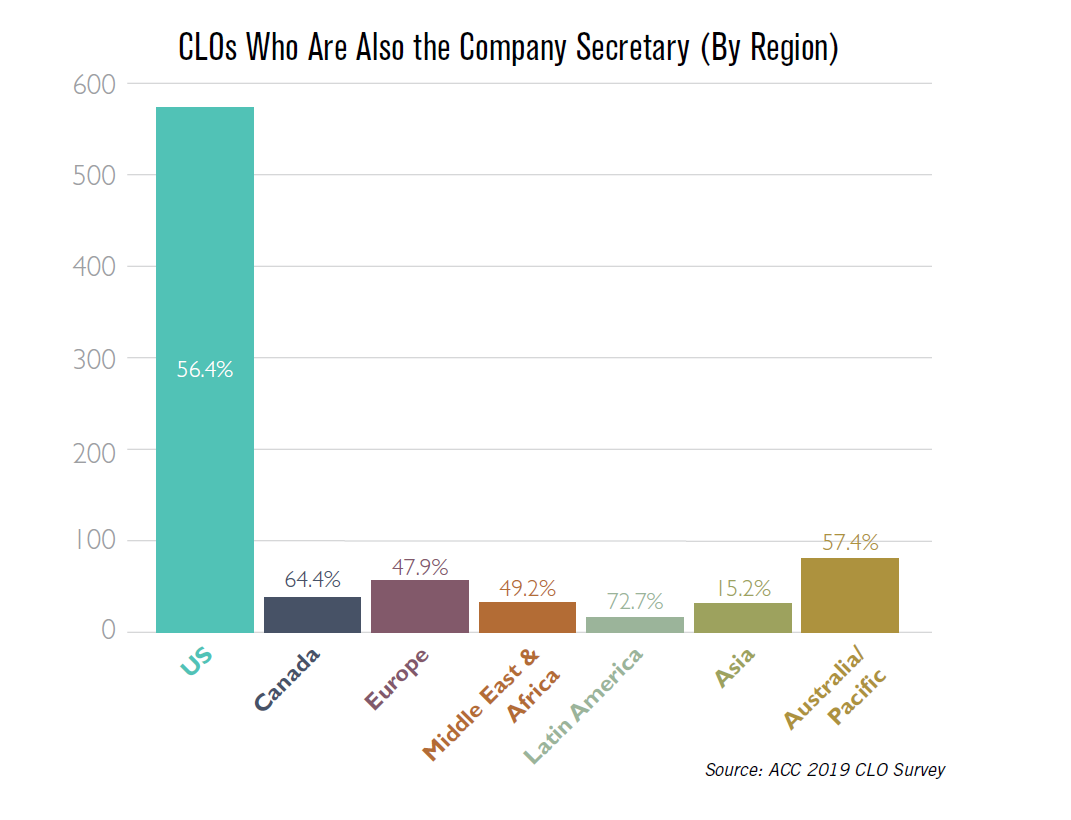

When looking at statistics, it becomes easier to discern whether there is real intent to put the general counsel in the position of the corporate secretary or keep them separate. In the United States, about 70 percent of members of the National Association of Corporate Directors have general counsel working in a dual role.28 However, in the United Kingdom, only around 40 percent of the top 100 companies’ general counsel wear both hats.29

While the decision to combine the roles of general counsel and corporate secretary depends on specific factors (i.e., business’ size, maturity, and business sector), the organizational structure (i.e., functional, geographical, or unit-based) plays a significant role as well.

Generally, smaller companies may have only a corporate secretary, but bigger companies with complex governance structures tend to separate the role of corporate secretary from the role of general counsel.30 Some of them even establish a separate administrative unit (such as an office of the corporate secretary). The corporate secretary also has different duties reporting structures. Some report solely to the board, while others report to a mixed group (like reporting to the board and also to the general counsel, chief executive officer, and/or chief financial officer). When reporting only to the board, the corporate secretary is also appointed by board members, rather than by the chief executive officer, and has her compensation set by the board. The rationale behind this is to make sure that the corporate secretary has some independence to perform her duties, which could involve the oversight of board decisions affecting the performance of the company’s top managers.

Combining the general counsel and the corporate secretary roles

In smaller and younger companies, with simpler governance structures, combining both positions should be the preferred option. In smaller environments, the in-house counsel acts like a “one-man-band.”31

But even in larger companies with complex governance levels, it may still be a good idea to keep one person in the dual role. Having a lawyer (or better, the in-house counsel) in close connection to the board on a frequent basis has multiple benefits. Being able to receive real-time legal advice is one of the primary assets.

Although having a lawyer performing the function of corporate secretary is not legally required, having a corporate secretary who possesses legal training has the advantage of offering the board all the benefits of having a lawyer in the same room. Most lawyers are trained to pay attention to details and to intuitively foresee legal risks; this is especially helpful during minute-taking. A lawyer can choose the proper words and anticipate underlying ideas that may prove useful when rereading minutes (such as in a courtroom).32

Privileged information can apply to board communications

The benefit of protecting sensitive information under the shield of the attorney-client privilege has some limits.33 The mere fact that the corporate secretary is a lawyer does not automatically safeguard all documents and communications.34 Some requirements and distinctions, like the separation of business from legal advice, have to be taken into consideration in order to benefit from this protection.35 Properly labeling the documents or exchange of communication is a good practice.36

Shortcut to building a board relationship

Trust is one of the essential elements of any attorney-client relationship, and for corporate secretaries who are also general counsel, this quality is even more important. A board who has a good and close relationship with the general counsel is more likely to involve the GC when legal advice is needed.37 Every new general counsel knows that this is true, especially if the GC wants to be regarded not only as the lawyer of the company, but also a true business partner. Wearing the corporate secretary hat together with the GC hat is a nice shortcut to establish a good presence within the board’s inner circle of confidence.38

When should the general counsel and the corporate secretary roles be separated?

If the general counsel is unable to exercise the corporate secretary function, there is still the option to outsource the corporate secretary role. Only time and experience will determine if this is a good idea from the governance standpoint.

On the flip side, bigger companies should also consider separating the roles for the following reasons.

Independence and separation of powers matter

Common practices or laws in some jurisdictions often have the company secretary directly reporting to the board’s chairman and the general counsel primarily reporting to the CEO. This may create sensitive situations when the general counsel needs to bring issues to the chairman independently. Unless there is seamless collaboration between the general counsel and the corporate secretary, the effective fulfillment of both tasks may require a combination of both roles in one person.

Nevertheless, an “ethical wall” to separate such powers may be the only way to avoid leaving the general counsel in the uncomfortable position of being “all things to all people.”

Non-legal tasks constitute a distracting factor affecting performance

The work of the corporate secretary is constant. It never stops: Once a meeting finishes, there are plenty of follow-up tasks — and the start of the preparations for the next meeting.39 Like any other project-management role, the corporate secretary has to make sure the decisions are executed and delegations were proper. Directors’ evaluations and, more importantly, succession planning can be too demanding for a general counsel to do alone. Corporate secretaries, nevertheless, are becoming very skillful at providing adequate support for their boards in their search to find adequate succession’s candidates.

Typical shareholder relations activities (such as issuing shares and certification, annual general meeting logistics, organizing questions and answers) are also a big part of the corporate secretary job description.

Not being able to perform both roles well could, ultimately, be frustrating and negatively affect a professional’s work-life balance. This is particularly significant because it might compromise the ability of the general counsel to exercise sound judgment when dealing with critical situations, such as providing advice regarding conflicts of interests.

Lawyers usually lack project management training

A substantive portion of the corporate secretary job deals with project management. Project management is commonly understood as “the applications of methods, tools, techniques, and competencies to a project,” including “the integrations of the various phases of the project life cycle.” In plain English, project management is simply getting the job finished — on time and within budget.40 Managing projects is more than a professional competence: It is a science that has its roots in the Roman Republic of 2,000 years ago.41 A lawyer isn’t expected to be familiar with typical project-management concepts and techniques,42 like “work-breakdown structure”43 or the “Gantt chart,”44 not to mention how to properly use the classic four phases of project management (i.e., planning, build-up, implementation, and closeout).45 It is therefore common to find a corporate secretary job posting that requires candidates to possess both degrees in law and business administration.

Conclusion

The role of corporate secretary has undoubtingly evolved to the point that is has become a sophisticated demanding profession. But the question remains: Should the general counsel also be the corporate secretary?

Ideally, the corporate secretary function should be separate from the general counsel function, provided that there is a seamless communication between them. The main reason for this segregation of roles is that the corporate secretary function is becoming increasingly complex and time-consuming. Wearing both hats may not be impossible, but to perform both roles well might be a mission impossible, except by very few “superpeople.”

This does not mean that the general counsel should not consider filling the corporate secretary role. Whereas there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to this matter, if the choice to be made is between a legally trained corporate secretary and a non-legally trained candidate, the prudent call should be to favor the former. Issues regarding protection of communications and attorney-client privilege should be carefully addressed, especially if a situation arises when it is unclear whether the advice primarily concerns a business matter or a legal question.

A prospective corporate secretary candidate should consider her aspirations and skills. If she is still inexperienced in board matters, but is willing to get a closer look, wearing two hats would likely be a helpful, eye-opening experience for her professional goals. Ideally, it is advisable for general counsel to keep in mind the demands of filling both roles simultaneously, as work-life balance has become one of the main challenges for any rewarding and stable career choice today.

And for those who decide to wear only the corporate secretary hat, this may be a rewarding choice for a full, influential career.

Notes

1 Nick Price, The Evolving Role of the Company Secretary, BoardEffect Blog, July 12, 2017 (last visited May 18, 2018). See also Dannette Smith, Brian Webb, Denise Kuprionis, The Corporate Secretary: An Overview of Duties and Responsibilities, Society of Corporate Secretaries and Governance Professionals, July 2013, (last visited May 18, 2018).

2 Paul Marcela, Andrew Vitrano, Should the Roles of Corporate Secretary and General Counsel be Separated? Cadence & Content: The Blog for Corporate Governance Professionals, April 18, 2017.

4 Ghita Alderman, Alison Dillon Kibirige, Christopher Mattox, Christopher Razook, Brenda Bowman, The Corporate Secretary: The Governance Professional Handbook, The International Finance Corporation, January 2016.

5 Some foreign countries have corporations’ laws expressly requiring companies to maintain a Corporate Secretary within their governance structure — like Andorra, Australia, Hong Kong, and

India. See Bruce Hanton et al., The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Corporate Governance 2017, Global Legal Group, June 19, 2017 (last visited May 18, 2018).

6 Mark Jackson, Harva Dockery, Quick-Counsel on Minutes, December 29, 2014.

7 Sections 142(a) and 224 of the Delaware General Corporation Law mention that “[o]ne of the officers shall have the duty to record the proceedings of the meetings of the stockholders and directors in a book to be kept for that purpose”, and “[a]ny records administered by or on behalf of the corporation in the regular course of its business, including its … minute books, may be kept on, or by means of, or be in the form of, any information storage device, method, or 1 or more electronic networks or databases (including 1 or more distributed electronic networks or databases), provided that the records so kept can be converted into clearly legible paper form within a reasonable time, and … shall be valid and admissible in evidence, and accepted for all other purposes, to the same extent as an original paper record of the same information would have been, provided the paper form accurately portrays the record”.

8 Section 1500 of the California Corporations Code states that “[e]ach corporation shall keep adequate and correct books and records of account and shall keep minutes of the proceedings of its shareholders, board and committees of the board and shall keep at its principal executive office, or at the office of its transfer agent or registrar, a record of its shareholders, giving the names and addresses of all shareholders and the number and class of shares held by each. Those minutes and other books and records shall be kept either in written form or in another form capable of being converted into clearly legible tangible form or in any combination of the foregoing. When minutes and other books and records are kept in a form capable of being converted into clearly legible paper form, the clearly legible paper form into which those minutes and other books and records are converted shall be admissible in evidence, and accepted for all other purposes, to the same extent as an original paper record of the same information would have been, provided that the paper form accurately portrays the record.”

9 Section 624(a) of the New York Business Corporation Law: “Each corporation shall keep correct and complete books and records of account and shall keep minutes of the proceedings of its shareholders, board and executive committee, if any, and shall keep at the office of the corporation in this state or at the office of its transfer agent or registrar in this state, a record containing the names and addresses of all shareholders, the number and class of shares held by each and the dates when they respectively became the owners of record thereof. Any of the foregoing books, minutes or records may be in written form or in any other form capable of being converted into written form within a reasonable time.”

10 Section 13(b)(2)(A) and (7) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 require corporations to “make and keep books, records, and accounts, which, in reasonable detail, accurately and fairly reflect the transactions and dispositions of the assets of the issuer”, in “such level of detail and degree of assurance as would satisfy prudent officials in the conduct of their own affairs.

11 A succinct description about the role of the Company Secretary in corporate governance can be found here: Stephen Giove, Robert Treuhold, Corporate Governance and Directors’ Duties Guide: United States, InfoPAK, Association of Corporate Counsel, January 2016. See also Stéphanie Lesage, Lillian Moyano Yob, Leading Practices in Board Orientation and Education, Association of Corporate Counsel, May 16, 2014.

12 A good list of basics of board’s minutes can be found here: Edward T. Paulis III, Preparing your board before litigation: a primer on defending board actions, preserving confidential information, and managing risk, ACC Docket Magazine, Vol. 34 No. 4 (2016).

13 The Disney case is generally referred collectively to all the opinions both in the Supreme Court of Delaware and in the Chancery Court. The first opinion was In re the Walt Disney Co. Derivative Litigation, which dismissed the original complaint, 731 A.2d 342 (Del. Ch. 1998). The appeal was Brehm v. Eisner, 746 A.2d 244 (Del. 2000), granting plaintiffs leave to replead in part. Following the appeal, In re the Walt Disney Co. Derivative Litigation, 825 A.2d 275 (Del. Ch. 2003), dealt with the denied motion to dismiss the amended complaint. After discovery, Ovitz moved for summary judgment that was granted and denied in part in In re Walt Disney Company Derivative Litigation, No. 15452, 2004 WL 2050138 (Del. Ch. Sept. 10, 2004). The opinion, after the trial, was rendered in In re the Walt Disney Company Derivative Litigation, 907 A.2d 693 (Del. Ch. 2005), and the final decision by the Supreme Court was In re Walt Disney Co. Derivative Litigation, 906 A.2d 27 (Del. 2006).

14 In re Walt Disney Co. Derivative Litigation, 906 A.2d 27 (Del. 2006).

15 In re Netsmart Technologies, Inc. Shareholders Litigation 924 A.2d 171 (Del.Ch. 2007).

16 Because of the lack of minutes, the Delaware Chancery Court cast doubt on the veracity of the company’s record, especially because a committee of the board approved all of the minutes for over five months at a single meeting held after litigation commenced. In the court’s words, “that tardy, omnibus consideration of meeting minutes is, to state the obvious, not confidence- inspiring.” The court then found the directors had breached their fiduciary duties in the sale process and, consequently, the court enjoined the merger.

17 See the Order of Dismissal by the Vice Chancellor of Delaware’s Court of Chancery granted on October 27, 2008 (docket entry # 27045818).

18 A good advice on how to best describe the board’s deliberations in the minutes express that “[r]ecording the general fact that the directors discussed or deliberated about an issue is critically important. However, what a particular director said about a particular issue is usually less important. For that reason, and to avoid errors in attribution, the secretary’s notes and official minutes generally should use collective or passive-voice descriptions (e.g., ‘the directors discussed the matter’ or ‘a discussion ensued’)”. See Bradley J. Bondi, Bart Friedman, Corporate Secretary Guidelines: Taking Notes and Preparing Official Minutes, August 2, 2016, (last visited May 18, 2018).

19 Minutes are essential to refresh memories of what the board considered and how decisions were taken, a must when depositions or witness testimony occur years after the board’s meeting. See J. Steven Patterson et al., Strategies for Achieving the Well-Structured Board Meeting, Association of Corporate Counsel, July 17, 2014, (last visited May 18, 2018).

20 Paul Marcela, Corporate Secretaries and the Private Board, Private Company Director: The Magazine for Private Company Governance, November 2016, (last visited May 18, 2018).

22 Referring the challenge of providing legal advice and drafting minutes at the same time, See the interview with the former Legal Director at Royal Dutch Shell (Beat Hess, How the General Counsel has Become a Trusted Advisor to the Board, The General Counsel and the Board, The Legal Professionals Practice No. 3 (2011), Egon Zehnder International (last visited May 18, 2018).

23 According to the Society of Corporate Secretaries & Governance Professionals, “[t]he style of minutes is determined in large part by the personal preferences of the Chairman of the Board, the Corporate Secretary, other senior officers of the corporation, and the directors, as well as by tradition within the company. Certain forms of minutes may be provided by the corporation’s outside counsel and the form of certain resolutions may accommodate requirements of external stakeholders, such as financial institutions. One of the most important points about the style of minutes is that it should remain consistent.“ Corporate Minutes–A Publication for the Corporate Secretary, Feb. 2014, (last visited May 23, 2019), p. 12.

24 Other important company’s norms shall also be under the Corporate Secretary oversight, like committee charters, governance guidelines and, in case of global business, the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (FCPA).

25 See Paul Marcela, Corporate Secretaries and the Private Board, Private Company Director: The Magazine for Private Company Governance, November 2016, (last visited May 18, 2018).

26 The facilitator’s attribute can be described as the ability to “look at the bigger picture and make sure everybody’s talking to each other”. See Rose Marie Glazer, Tiffani R. Alexander, Q&A with the EiC on Getting a Seat at the Table, ACC Docket Magazine, December 22, 2017.

27 In the real corporate world, problems normally happen. It is just a matter of time depending on the risk appetite and risk tolerance of each business configuration. If no risk is involved, there is a good chance that also no business is involved. Risk appetite is deemed as “the level of risk that an organization is willing to take in the pursuit of its objectives.” Risk tolerance is “the amount of risk that an organization could accept without a serious threat to its financial stability.” The last is commonly measurable in quantity. See Ghita Alderman, Alison Dillon Kibirige, Christopher Mattox, Christopher Razook, Brenda Bowman, The Corporate Secretary: The Governance Professional Handbook, The International Finance Corporation, January 2016.

28 American Corporate Counsel Association, ACCA/NACD Corporate Director & Corporate Counsel Poll on Corporate Governance, May 29, 2003.

29 Rank by market capitalization listed on the London Stock Exchange (FTSE). Ian Maurice, General Counsel and Company Secretary: To Combine or Not to Combine, Egon Zehnder International, July 31, 2011, (last visited May 18, 2018).

30 Noting that “the rationale for this split is not so much that the GC should not be the mere minutes-taker of the board, but that he [or she] must concentrate on the breadth of tasks in relation to functional and business expertise as well as managerial skills”. Jörg Thierfelder, The Role of the General Counsel with the Board of Directors, The General Counsel and the Board, The Legal Professionals Practice No. 3 (2011), Egon Zehnder International (last visited May 18, 2018).

31 Bruce N. Hawthorne, Jeffrey M. Stein, GC Growth: How The Law Department Contributes To Improved Board Performance, ACC Docket Magazine, Vol. 33 No. 6 (2015).

32 Conversely, when the Corporate Secretary has a lawyer background, the standard for assessing the fulfillment of duties regarding the board’s obligations can be much higher than the one expected of a non-lawyer. In Australia (ASIC v Hellicar, 2012 - the James Hardie case), a court found that “the responsibilities of the company secretary (who was also a qualified lawyer) extended to providing advice to the board about meeting disclosure obligations and identifying defects in reports being considered by the board, because he possessed special skills as a lawyer.” Holly Gregory et. al., Corporate Governance: Board structures and directors’ duties in 33 jurisdictions worldwide, Law Business Research, June 2014, (last visited May 18, 2018).

33 Norton Rose Fulbright, Are Minutes of Board Meetings Protected by Privilege? Privilege and document protection - FAQs.

34 One of the mechanisms employed by courts in order to determine if a communication is protected by the attorney-client privilege can be found in the primary purpose test. Just because a legal issue can be identified that relates to on-going communications does not justify shielding them from discovery. The lawyer’s role as a lawyer must be primary. See In re Vioxx Prod. Liab. Litig., 501 F. Supp. 2d 789, 798 (E.D. La. 2007).

35 Expressly identifying in the minutes that a lawyer is present to the meeting is generally the first, but not the only step.

36 A good suggestion on how to proper label in the minutes should contain something like “Privileged Attorney-Client Communication: General Counsel provided legal advice to board on the matter of so-and-so.”

37 When the General Counsel is not the same person, he or she spends less time with the board. Broc Romanek, Should the General Counsel Also Serve as the Corporate Secretary? TheCorporateCounsel Blog, May 20, 2014, (last visited May 18, 2018).

38 As a good illustration of how candor and trust are a must inside the boardroom, see James Stewart, The Kona Files - Loose Lips at Hewlett-Packard, The New Yorker, February 19, 2007, (last visited May 18, 2018).

39 Nicholas J. Price, How a Corporate Secretary Should Prepare for a Board Meeting, Diligent Corporation Blog, December 1, 2017, (last visited May 18, 2018).

40 Joe Knight, Roger Thomas, Brad Angus, The Dirty Little Secret of Project Management, Harvard Business Review, Harvard Business School Publishing, March 11, 2003, (last visited May 18, 2018).

41 The multi-volume work entitled De Architectura from Marcus Vitruvius Pollio is considered one of the first sources of the development of the modern discipline of project management, which was applied mainly in civil engineering until the 20th Century. In fact, the father of architecture describes at the introduction of the work’s tenth volume a concept that is surprisingly similar to what project management is understood today when addressing the elements and limitations on budget, time and quality of constructions, or what would be considered a well-executed project. See William P. Thayer, Vitruvius: On Architecture, Jun 1, 2017, (last visited May 18, 2018).

42 Paul Marcela, Separating The Corporate Secretary And General Counsel Roles, February 7, 2017.

43 Defense Systems Management College, Systems engineering fundamentals: supplementary text, January 2001, p. 86, (last visited May 18, 2018).

44 Henry Laurence Gantt, Work, Wages, and Profits: Their Influence on the Cost of Living, Engineering Magazine, 1911, (last visited May 18, 2018).

45 Harvard Business Review Staff, The Four Phases of Project Management, Harvard Business Review, Harvard Business School Publishing, November 3, 2016, (last visited May 18, 2018).