CHEAT SHEET

- A sleeping giant. The market for marijuana products in the United States is estimated at $50 billion, although this revenue remains largely untapped.

- An uneasy truce. In 2013, the US Department of Justice established a formal policy of non-prosecution for marijuana businesses operating under state law.

- Keeping their hands clean. Due to federal requirements on financial institutions processing marijuana-related transactions, many such businesses operate in cash.

- Continuing uncertainty. Despite popular support for decriminalization and changing state regimes, investment in the industry remains fraught with difficulty.

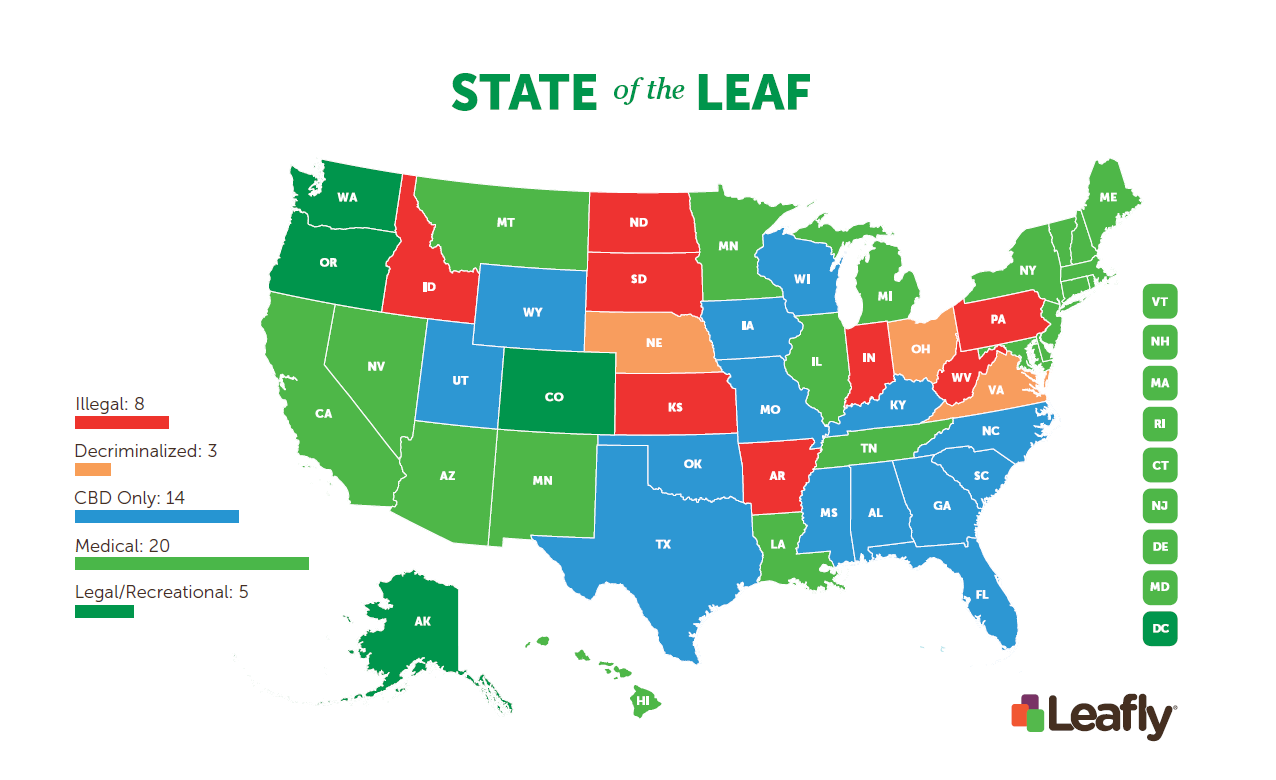

Despite the rapid and massive shift toward cannabis legalization — well over half of the US population lives in a state where medical cannabis is legal, and more than eight in 10 Americans consistently support the legalization of medical cannabis — cannabis remains classified as a Schedule I drug, those drugs classified as having no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Although many drugs are scheduled via rulemaking, marijuana was placed in Schedule I by statute, as part of the passage of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, commonly referred to by its short title, the Controlled Substances Act or CSA. As a result, it could be rescheduled by administrative means or by legislation. The US Drug Enforcement Administration has rejected several attempts to reschedule cannabis via the administrative path, but several rescheduling bills are pending in Congress. However, absent such rescheduling, the possession, manufacture and distribution of cannabis in states with legal cannabis regimes is technically in conflict with federal law. In addition, careless operations could pose accessory liability and money laundering risks.

Yet, the federal government has, to a large degree, tolerated the existence of an emerging commercial cannabis industry, an industry that operates in a netherworld characterized by a conflict between state and federal law. The allure of an estimated $50 billion domestic industry ($150-200 billion globally) presents an incredible market opportunity, which has attracted a broad spectrum of interested players.

As general counsel at Privateer Holdings, the leading private equity firm investing in legal cannabis worldwide, and a former federal narcotics investigator with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), I have a unique perspective of the complex legal and regulatory rules governing this rapidly changing industry. Lawyers who are asked to advise on cannabis-related endeavors need to have knowledge of a broad range of somewhat unusual practice areas including federal law, regulatory work and commercial transactions.

Federal guidance

The guiding light for most businesses operating in the legal cannabis industry to date has been a memorandum issued by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) in August 2013 entitled Guidance Regarding Marijuana Enforcement. Dubbed the “Cole Memo,” due to its author (then-Deputy US Attorney General James Cole), it established a formal policy of non-prosecution (based upon the principle of prosecutorial discretion), provided that certain factors were not implicated. Those factors include such common-sense issues as preventing access to minors, preventing involvement of criminal enterprises, preventing diversion to other states, preventing drug-related violence and preventing drugged driving. Importantly, the guidance is premised upon the existence of a robust state-level regulatory regime.

It should be noted that the memo is guidance directed to federal prosecutors, and thus is non-binding and cannot be used as a defense in court. In addition, at least one district court has ruled that the existence of a state-authorized marijuana regime cannot be used as a shield against federal prosecution. However, as a policy matter, the DOJ and its constituent agencies have made the express decision not to intervene in state-authorized cannabis regimes, thereby implicitly endorsing their existence. Federal marijuana seizures and prosecutions in states where marijuana has been legalized have dropped significantly, and, to the best of my knowledge, every federal prosecution presently pending in a cannabis-legal state was initiated prior to the Cole Memo, or resulted from activity specifically enumerated in the Cole Memo. Furthermore, service providers face fewer obstacles, both as a policy matter and a legal matter. With respect to the former, the DOJ is focused on criminal trafficking, not on vendors who provide standard business services; on the latter, accessory liability (otherwise known as aiding and abetting) requires intent to facilitate the commission of a crime, a mental state that should in nearly all instances be lacking.

Meanwhile, the cannabis industry’s transition from illicit to licit has created the unusual dilemma of a massive consumer industry that lacks access to legitimate banking services — posing a significant threat to public safety in communities around the country. There is a strong argument that such access would actually enhance compliance efforts by serving as a gatekeeper and providing a paper trail documenting all financial transactions relating to the entity. Yet, the federal government has only grudgingly taken steps to provide such access.

Following the issuance of the Cole Memo, the cannabis industry eagerly awaited promised follow-up guidance on banking. For years, financial institutions had mostly refused to bank marijuana-related businesses because of the institutions’ obligations under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) and the federal money laundering statutes, which criminalize certain financial and monetary transactions involving the proceeds of a “Specified Unlawful Activity” (including the manufacture and distribution of marijuana). In February 2014, the DOJ and the US Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) released parallel memos, captioned Guidance Regarding Marijuana Related Financial Crimes and BSA Expectations Regarding Marijuana-Related Business, respectively. The DOJ memo encourages prosecutors to employ the same standards set forth in the Cole Memo to make determinations regarding the prosecution of marijuana-related businesses who may technically be committing money-laundering offenses simply by conducting a financial transaction.

The FinCEN memo clarified the conditions under which financial institutions can provide services to marijuana-related businesses. The FinCEN memo states that financial institutions have broad discretion on whether to open, close or refuse any individual account, which are often dictated by the risk profile of the customer, the compliance burden placed on the financial institution, or some combination thereof. Under the BSA and the PATRIOT Act, financial institutions have a number of monitoring and reporting obligations, including client identification (Know Your Client or KYC) and the implementation of robust anti-money laundering (AML) programs. The former is generally satisfied by a customer due diligence program, and the latter, in large part by reporting requirements. This reporting is satisfied primarily by means of Currency Transactions Reports (CTR) and Suspicious Activity Reports (SAR). CTRs are required whenever a cash transaction (receipt or disbursement) exceeding $10,000 is conducted. SARs are required whenever the institution has reason to suspect the transaction involves criminal proceeds, is designed to evade reporting requirements, or there is no reasonable explanation for the transaction. SARs are often generated as the result of “structuring” — the use of multiple deposits of less than $10,000 in order to evade the CTR requirement.

Since virtually every transaction conducted by a marijuana-related business would technically warrant a SAR, the FinCEN memo also created the following three new categories of SARs — “marijuana-limited,” “marijuana-termination,” and “marijuana-priority.” Marijuana-limited SARs are used for routine transactions involving marijuana-related businesses, giving the government broad access to the history of that particular entity’s financial transactions — information that would otherwise require a grand jury subpoena to obtain. Marijuana-termination SARs are filed when a financial institution closes the account of a marijuana-related business. Finally, marijuana-priority SARs are filed if the financial institution believes that state law or a Cole Memo condition is being violated. FinCEN provided an extensive list of “red flags,” which include the following: unusually high revenue or activity, especially in comparison to local competitors; inability to demonstrate compliance with state law; structured deposits or rapid movement of funds; third party deposits or transactions on behalf of third parties.

Businesses and vendors face numerous challenges in advertising cannabis products, even in states where marijuana is legal.

In July 2015, a local Colorado television station agreed to broadcast commercials for a cannabis retailer, then reversed course shortly before the spots were slated to air, pointing to “lack of clarity” in the federal regulations as the basis for the decision. While the advertisements arguably complied with Colorado regulations regarding audience and reach, they were stymied in their quest to make it to the small screen.

The reluctance of the broadcaster to air the spots highlights the fallout from the federal-state conflict. The federal classification of marijuana and the lack of any guidance by the FCC to media outlets with respect to the product, or to their obligations with respect to local programming, has left businesses and media outlets at a standstill. While there is some precedent that the FCC could not enforce a ban on a commercial promoting products that are legal under state law — which, arguably, would support the position that it is not against the public interest, at least in that state — there are no FCC rulings or policy statements relating to cannabis. This “lack of clarity” has led stations to avoid placing their licenses in jeopardy and potentially incurring fines by airing commercials featuring cannabis products.

The hurdles do not end with broadcast media. Internet advertising has become just as challenging due to the trend toward platforms opting to refuse advertisers or products that may be “high risk.” Social media sites and vendors such as email communication platforms prohibit promotion of or reference to illegal substances. Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store have denied or removed multiple apps with little or no justification. Few providers are willing to delve into the nuances associated with the state law/federal law dichotomy.

In light of this, attorneys for clients on both sides of the media fence need to have a clear understanding of their clients’ risk tolerance in this area and should pay close attention to the vendor-client agreements governing the buys and licenses. Cannabis businesses should be prepared to hear “no” and will need to think more broadly about marketing strategy. At least in the near term, they may need to resort to other communication methods, and often will have to forego usual brand positioning statements and direct offers for alternate language, to avoid violating contractual obligations or getting caught in the crosshairs of the federal-state conflict.

The FinCEN memo essentially required that financial institutions conduct enhanced due diligence (EDD) with respect to marijuana-related businesses. That EDD includes verifying state licenses; reviewing the license application and related documents; verifying information with the state licensing authority; developing an understanding of the client’s expected business activity; ongoing monitoring of open sources for potentially adverse information about the client; ongoing monitoring of account activity; and periodic refreshing of the entire EDD package.

Taken as a whole, the FinCEN requirements create an enormous burden on financial institutions, which make banking marijuana businesses less attractive. The required EDD would likely necessitate a dedicated compliance team with familiarity of the marijuana industry at each financial institution. Clearly, most banks have weighed the costs of those burdens (and the attendant risks) against the value of the potential new accounts, and have landed squarely in the camp of “not worth it.” The Colorado Bankers Association described FinCEN’s guidance thusly: “At best this amounts to ‘serve these customers at your own risk.’” However, it is well known that a number of regional financial institutions are quietly servicing the cannabis industry, and doing so without issue.

However, a business contemplating the provision of services to a marijuana-related business would be well advised to conduct a similar level of diligence before proceeding. Verifying licensure and a review of open source material and social media postings are simple and effective filtering mechanisms.

Cash is king

A nearly all-cash marijuana industry makes the industry more difficult to tax and regulate, and presents numerous and significant public safety concerns. Many marijuana-related business, and their service providers, overlook the requirement to file Form 8300 with the IRS when receiving more than $10,000 in cash in a transaction or series of related transactions. Meanwhile, efforts to provide access to banking services continue, but without much success.

In November 2014, Fourth Corner Credit Union received a charter from the State of Colorado. Fourth Corner was organized specifically to service the marijuana industry, with the encouragement and support of state officials. While it claimed it had a robust compliance program developed by world-renowned anti-money laundering experts, its board of directors was populated primarily with medical marijuana advocates and business owners, rather than bankers. Fourth Corner applied for the statutorily required share-deposit insurance from the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), which was denied in July 2015 on the basis of “fundamental concerns about the inherent risks of [Fourth Corner’s] business model.” Arguably, the stated reason was a justifiable basis pursuant to the NCUA’s mandate to consider, among other factors, the “management policies of the applicant” and the “economic advisability of insuring the applicant without undue risk of the fund.” Similarly, a request for a master account from the Federal Reserve, which typically is a mere procedural hurdle, was denied two weeks later. Fourth Corner subsequently filed federal lawsuits seeking declaratory relief against both the NCUA and the Kansas City Fed, alleging they conspired to deny Fourth Corner access to the banking system despite providing similar services to other financial institutions that service the marijuana industry (albeit in a more limited fashion). Those lawsuits are pending, and the issue of whether the Federal Reserve has the discretion to deny such a request is believed to be one of first impression, although the Fed’s assertion of its authority to condition (but not deny) approvals has, in at least one instance, been approved by the courts without a decision on the merits.

In January 2015, MBank, a small Oregon-chartered bank, publicly announced that it would begin accepting marijuana-related deposits in Colorado, which legalized both medical and recreational marijuana. Rather than establishing a physical presence in Colorado, they would use an armored car service to make cash pickups and deposit the money into their Federal Reserve account in Denver. Despite a healthy dose of skepticism from the Colorado Bankers Association, Jef Baker, president and CEO of MBank, said at the time, “It’s a bold maneuver and not one for a lot of folks to take on… We looked to regulators, both state and federal, to help us come to the conclusion that we can do banking in this sector.”

Less than a week later, MBank retreated, announcing it would no longer service Colorado marijuana-related business, and closed the five accounts it had already opened. Then MBank went further and abandoned the marijuana-related sector entirely, closing an additional 70 accounts in Oregon and Washington. Publicly, MBank claimed that it had been inundated with potential customers and did not have the resources necessary to maintain its compliance obligations. Privately, many speculated that MBank caved under pressure from federal banking regulators.

Some members of Congress have attempted to proffer solutions. Proposed bill HR 2076, the Marijuana Business Access to Banking Act, would create a safe harbor for financial institutions that offer banking services to state-licensed marijuana-related businesses. The omnibus spending bills of both 2014 and 2015 have included provisions that prohibit the DOJ from expending funds to “prevent [States] from implementing their own State laws that authorize the use, distribution, possession or cultivation of medical marijuana.” Not surprisingly, the DOJ has interpreted those provisions as applying only to actions against state officials or entities, and not to individuals operating under those state laws.

In the meantime, most marijuana-related business banking is predicated upon relationships with small regional banks and credit unions. As a result, most such businesses treat their banking relationships as a trade secret. Service providers should inquire as to a potential marijuana-related client’s banking situation, and consider whether they are willing to deal in cash.

Securities

In the absence of the availability of debt or leverage through financial institutions, marijuana-related businesses have turned to securities offerings, both public and private.

In May 2014, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) suspended the stock trading of five companies because of questions regarding the accuracy of publicly available information about their operations and, in some cases, allegations of unlawful sale of securities and market manipulation. What made these otherwise routine suspensions noteworthy was the nature of the companies’ operations: They were all part of the marijuana industry. Shortly thereafter, both the SEC and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) issued investor alerts related to marijuana stock scams, and three months later, four stock promoters associated with two of the five affected companies were charged with federal civil and criminal offenses related to the pump-and-dump scheme.

In January 2015, the SEC allowed a share registration to proceed for Terra Tech, a company whose business model includes the cultivation and sale of marijuana. “Allowed” is the operative word, since the SEC declined to accelerate the registration, which would be the norm for underwritten offerings but which also requires a finding that the acceleration is in the public interest. Without acceleration, the registration becomes effective 20 days later, which typically causes problems for the underwriters because they can’t commit to an unknown future price. However, in this case, the registration was only for resale of stock from a convertible note, so the lack of acceleration was not a problem.

Many at the time pointed to the SEC action as proof of the federal government’s acceptance of commercial cannabis operations. Terra Tech CEO Derek Peterson described the SEC as having “tolerance for companies in this space,” and prohibitionist Kevin Sabet claimed “the federal government is essentially giving the green light to a company to break federal law.” However, the SEC staff examines registration statements only for compliance with disclosure and accounting requirements. It does not evaluate the merits of the securities offering, nor evaluate the legality of the underlying business.

Meanwhile, there are now, by one count, over 300 public companies claiming to be operating in the cannabis space — up from 13 in 2013. These stocks are thus far exclusively traded over the loosely regulated secondary markets, primarily microcaps achieved via reverse mergers. Many appear to be focused on generating short-term value for shareholders (many of whom are insiders) rather than building long-term fundamentals. Exit and IPO opportunities are almost non-existent.

Many experts believe the industry currently lacks the fundamentals to justify public offerings. The industry is immature, highly fragmented and lacking professional managers. The rush to go public is fundamentally at odds with the lack of measurable data. There is hardly enough data for institutional investors to make an informed investment decision (and in most cases, that decision is to sit this one out), let alone retail investors. Many retail investors have very little understanding of the reporting differences between over-the-counter and major exchanges. As a result, retail investors are more susceptible to misleading information, and less equipped to properly evaluate opportunities. In fact, many of the analyst reports are written by underwriters or syndicate members involved in the very offerings they purport to evaluate, which raises questions about their objectivity. Unscrupulous stock promoters are frequently found running email marketing campaigns, trolling forums, and releasing promotional press releases, efforts that reek of pump-and-dump scams. In 2014, investors in small cannabis companies in the United States lost $23 billion. That loss is being borne almost exclusively by retail investors who can ill afford it, while accredited investors, for the most part, realize that investments with this risk profile should only constitute a small portion of their overall portfolio.

The green rush and the need for due diligence

There is a green rush mentality fueled by massive media attention that is leading many people to make unwise business and investment decisions out of fear of missing out on the next big trend. Right now, this seems to be an area that should be reserved for sophisticated investors.

As a result, investments into the cannabis space require an extraordinary amount of due diligence. For private offerings, the risk factors section of an offering memorandum or registration statement is not for the faint of heart — but, nothing contained therein should come as a surprise to an investor considering this space. However, they do need to be scrutinized. It was widely reported that the offering memorandum for Diego Pellicer, a company launched with great fanfare in 2013, casually mentioned that it had been subpoenaed by the local US Attorney’s Office — obviously a major red flag.

In addition to standard investment or M&A diligence, potential investors need to delve into the target’s compliance record, including licensure, inventory control and supply chain logistics. Examination of those records is complicated by the patchwork of state regulations across the country, a situation that precludes a one-size-fits-all approach to diligence in this space. In fact, several jurisdictions prohibit out-of-state investment — ostensibly an attempt to comply with Cole Memo’s directions to prevent out-of-state diversion, but a prohibition that likely implicates several constitutional issues, including the Privileges and Immunities Clause and the Dormant Commerce Clause. Financial arrangements, corporate formalities and insurance coverages require extra scrutiny.

Even the provision of services to marijuana-related businesses requires a certain level of diligence. Several courts have invalidated contracts involving cannabis businesses as void as against public policy and others have declined to offer bankruptcy protection. Perhaps the most pernicious development is the use of the private right of action under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) by prohibitionists to target those who provide services to marijuana-related businesses, including contractors, banks and accountants. Although RICO’s preamble states that the law was intended to eradicate organized crime and its influence on legitimate business, the act’s expansive language has led courts to construe it broadly. These lawsuits essentially amount to a claim that the defendant’s state-authorized marijuana-related activity proximately caused harm to the plaintiff ’s business. The proximate cause requirement means that a plaintiff must show some direct relationship between the injury asserted and the conduct alleged, a standard that generally excludes unforeseeable or speculative injuries. A single prohibitionist group is responsible for both of the pending RICO suits, which allege injuries ranging from diminished property values to noxious odors and reduced retail traffic. It seems likely that such claims will be difficult to prevail on, but they nonetheless represent a costly burden for the defendants and have served to reinforce the skittishness of other service providers.

The real estate adage is particularly relevant in these cases — location, location, location. A well-sited marijuana-related business, away from schools and residential areas, and in a municipality that welcomes these types of businesses, can serve to effectively head off the plaintiff’s bar. Similarly, forum selection clauses in vendor contracts are vitally important — generally, it’s safe to assume that a court in Washington or Colorado is going to be more forgiving of the nature of the marijuana-related business than a court in Oklahoma. Lastly, ensure you have a full set of representations and warranties from a marijuana-related business that cover all of its contemplated activities, and beware of the boilerplate “compliance with all applicable laws.” Those clauses will need to be tailored a little more carefully in order to avoid a technical breach owing to the status of some of their activities under in light of the federal-state conflict.

International considerations

Some investors have looked to overseas opportunities as a safe haven. Several countries, including Canada, have national medical cannabis regimes overseen by a federal regulator, eliminating the federal-state conflict that exists in the United States. In October 2014, Reuters published a sensationalized article that claimed “the DEA is ‘most interested’ in US investors in Canadian marijuana firms.” The article cited a risk specialist who said, “I don’t see any way around [violating federal law],” and an unnamed former DEA official who claimed such investments were “extremely reckless” and “would have the taint of drug proceeds,” and that any attorneys advising such investors “grossly underserved” them. This article caused a flurry of concern, but that concern was, and is, unfounded.

At least one federal court has held that there is no violation of the conspiracy statute where the object of the conspiracy was to possess a controlled substance outside the United States without the intent to distribute the controlled substance in the United States. Furthermore, if there is no underlying substantive drug offense (including a conspiracy offense), then there is no Specified Unlawful Activity (SUA) required to substantiate a money laundering offense. In other words, if the act is legal in the offshore jurisdiction, there is no domestic criminal offense.

But foreign investments can run afoul of securities laws in other ways. In late 2014, a Michigan-based pink-sheets company that distributes dietary supplements, Creative Edge Nutrition, formed a Canadian subsidiary called CEN Biotech, which then applied to the government of Canada for authorization to produce and distribute medical cannabis. The company, and its CEO, made a number of outlandish and misleading statements that implied that CEN Biotech had received authorization, as well as other dubious claims, which served to pump up the company’s stock. When Toronto’s biggest newspapers began reporting on the irregularities, Canadian regulators finally took notice and denied the company’s application. Meanwhile, insiders made some questionable transactions, selling off stock at the peak and shorting it just before announcing that their license application was denied. Canadian securities regulators were powerless since the parent company traded on a US pink-sheet market, and it’s not clear whether the SEC ever investigated.

Oftentimes, skittish service providers will ask for a legal opinion regarding a marijuana-related business’ activities. When narrowly tailored to a specific issue, legal opinions can provide necessary assurances, but it’s important to realize that the broader the issue, the more caveats will be included. If you are paying for the legal opinion, be prepared for an extraordinarily large bill unless the writer is already familiar with the complex legal issues unique to the cannabis industry.

Five things in-house counsel need to know about doing business with a cannabis company.

Understand the risks. The federal government’s tolerance of legal cannabis is predicated on robust state regulations, which vary widely from state and state and are constantly being refined and updated. Make sure you understand the applicable laws and regulations in your jurisdiction, or that of a potential business partner or client.

Diligence, diligence, diligence. No matter the nature or value of the transaction, at the very least you should verify that the cannabis business is properly licensed and in good standing, be comfortable with the management team’s qualifications, and thoroughly understand the business model.

Governing law and venue. Choose a state where cannabis is legal and well-regulated to help ensure contract enforceability and familiarity with relevant issues. Washington and Colorado are good choices; California and New York, while regulated to some degree, are not ideal.

Re-evaluate boilerplate. Many typically boilerplate clauses will need to be narrowly tailored to avoid a technical breach due to federal law. For instance, compliance with “all applicable laws” will need to be broken down into specifics; at a minimum, be sure to insist on compliance with state regulations and the Cole Memo.

Payment terms. Unless you are willing to accept cash payments, confirm that the cannabis business has access to traditional banking services.

Conclusion

Despite all of the challenges of the nascent cannabis industry, it represents an enormous opportunity. Attorneys, entrepreneurs and others are faced with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to help shape a massive new industry, one which has the potential to generate enormous financial returns, but also enormous social returns. A significant catalyst for that change is the entry of top tier professional service providers into the cannabis industry.

Attorneys tasked with advising clients considering the space — whether directly or as a service provider — must have a broad understanding of multiple practice areas, including federal law, regulatory work, corporate governance, contracts and finance. This complex intersection of law presents significant challenges to the uninitiated. Lately, specialized bar associations and even law school classes have formed to focus on the subject. All of the issues discussed above — and many others — should be carefully considered when evaluating an opportunity in the emerging cannabis industry. Until federal law changes, a certain level of risk tolerance is required. For those with the appetite, the potential rewards — both financial and social — are significant.

Further Reading

See, e.g., Order Denying Motion to Dismiss and Motion for Reconsideration, United States v. Firestack-Harvey et al., No. CR-13-24-FVS (E.D. Wash. June 24, 2014); United States v. Sandusky, No. 13-50025, 2014 WL 1004075, at *1 (9th Cir. March 17, 2014).

See 18 USC §§ 1956 and 1957.

12 USC §1781(c).

See FCCU v. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 1:15-CV-01633-RBJ (D. Colo. 2015) and FCCU v. NCUA, 1:15-CV-01634-REB. (D. Colo. 2015).

Eccles v. People’s Bank of Lakewood Village, 333 US 426 (1948), reh’g denied, 333 US 877.

See Hammer v. Today’s Health Care II, CV2011-051310, Az. Sup. Ct. 2012.

See In re Frank Anthony Arenas, Bk. No. 14-11406, Bankr. D. Colo. 2015.

18 USC § 1964(c).

See Safe Streets Alliance, et al., v. Alternative Holistic Healing, LLC, et al., Civ. No. 15-cv-00349-REB-CBS (D. Colo. 2015).

See United States v. Lopez-Vanegas, 493 F.3d 1305 (11th Cir. 2007).