CHEAT SHEET

- Find out who can hurt you. Some states deem restrictive covenants unenforceable depending on the status of the employee in question.

- Protect yourself appropriately. Match the restriction level on employees to the harm they can inflict on your company.

- Consider state law. You won’t need 50 covenants for 50 states, but a handful of “problem states” require individual attention.

- Don’t lose track. Find inspiration in different sorts of restrictive covenants with the included chart.

Your company is headquartered in Colorado but has thousands of employees in many jurisdictions across the United States. You are concerned — for good reason — that although the restrictive covenant you require employees to sign may be enforceable under Colorado law, the covenant may not be enforceable against your employees located in the other states where your company has offices. Large companies with employees located across the country need to consider the dangers of “one-size- fits-all” covenants.

Different states treat restrictive covenant agreements in surprisingly different ways. For example, although a restrictive covenant may be enforceable under Colorado law, chances are that covenant will not be enforced in a state like Virginia, where the courts in recent years have taken an increasingly strict view against restrictive covenants. Furthermore, although courts in Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Ohio will “blue-pencil” or modify overly broad restrictive covenants, overreaching is fatal in other states such as Virginia and Wisconsin, where courts strike down overbroad covenants in their entirety.

In addition to common law variations, a number of states have statutes governing employee covenants, some of which expressly prohibit non-compete agreements. California and North Dakota, for instance, have statutes that void most or all non-compete agreements. Oklahoma prohibits outright bans on competition, but allows customer non-solicitation agreements. On the other hand, states like Michigan, Florida, and in recent years, Georgia, allow non-competition agreements that are reasonable. In the midst of this morass of conflicting state laws, can you possibly administer a workable non-compete program in a multistate environment? Yes, if you begin by analyzing your workforce, your needs for protection, and your geographic presence.

Step one: Identify categories of employees against whom you need protection

First, an employer should identify the categories of employees for whom contractual protection is required. In other words, what employees can hurt you if they leave to join one of your competitors? Only senior level management employees? Or can sales representatives who control client relationships or have access to proprietary data harm the company? The type of employees against whom you seek protection matters a great deal in states like Colorado, where a statute provides that restrictive covenants can only be enforced against managerial and executive level employees and their professional staff, and are deemed unenforceable against sales representatives, unless necessary to protect trade secrets. In short, determining the employees from whom you need protection is the first step in drafting an enforceable restrictive covenant.

Step two: Identify the appropriate level of protection

The second consideration when drafting enforceable covenants is to identify the appropriate level of protection needed for each employee category. The goal is to make sure that the restrictions you impose on each type of employee match the harm those employees can inflict. Perhaps just a non-solicitation or confidentiality agreement will provide adequate protection with your sales force. In contrast, you may need a full-blown non-compete agreement for your senior level executives. In any event, determining the appropriate level of protection is of the utmost importance in states such as Virginia or Wisconsin, where overreach is likely fatal. In these states, courts will most likely refuse modification. Consequently, employers must carefully identify the minimum level of protection needed to secure the company’s interests, or risk a judicial finding that the covenant is overly broad and therefore void in its entirety.

Step three: Take state law into account

The third step is to take state law into account. Stated differently, now that you have identified the categories of employees against whom you require contractual restraints, and the appropriate level of protection for each type of employee, the next step is to make sure your agreements comply with the law in the states where your employees are located. Does this mean a national employer needs 50 or more contracts? No. Generally speaking, states can be broken into two categories: (1) “typical states;” and (2) so-called “problem states.” Problem states are those such as Louisiana, Oklahoma, and others where the legal prerequisites for enforceability are unique or where there is no room for error because any amount of overreach is likely fatal. “Typical states” are those such as Ohio or Pennsylvania where (1) restrictive covenants are likely to be enforced so long as they are reasonable in scope and duration, and they are necessary to protect a legitimate business interest, and (2) the courts are empowered to modify — rather than completely strike down — a covenant found to be somewhat overbroad. Assuming you have done a good job with steps one and two above, your restrictive covenant probably will be enforceable in these states (of course, actual enforcement will depend on the facts of a given case). Moreover, in the event that you have overreached a bit, these states empower courts to modify overbroad restraints. For example, if your non-compete precludes competition within 50 miles, but a court determines that 30 miles will do the trick, most trial judges in “typical states” will modify the covenant to a 30-mile radius and enforce it as modified.

“Problem states” are those where the legal prerequisites for enforceability are unique or where there is no room for error because any amount of overbreadth is fatal. These states are Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Vermont, Virginia, South Carolina, and Wisconsin. For example, in Louisiana, a statute dictates that unless your restrictive covenant names the specific parishes — by name — within which the restraint applies, it will not be enforced. In Oklahoma, as noted above, a noncompete will not fly, but a customer non-solicitation agreement is likely to be enforced. In Virginia, a company is well advised to make certain that its non-compete is absolutely no more burdensome than necessary to protect a legitimate interest, or else the restraint will be deemed void in its entirety. Other states, like California and North Dakota, similarly present problems of their own and require some special attention to increase the likelihood that your covenant will be enforceable. Contrary to popular belief, employers can find ways to protect themselves in California and North Dakota despite the statutory proscription on restrictive covenants.

Choice of law/choice of forum clauses may not solve your problem

Some companies try to circumvent these problems by including a choice of forum and/or choice of law provision in their covenants. Although this course is potentially beneficial, this idea is not a panacea to your problems and presents various risks. For example, courts do not always honor choice of forum provisions. If your former employee worked for you in a state far across the country, there is case law to support the proposition that a choice of forum clause should not be enforced. Additionally, the danger of including a choice of law provision in a restrictive covenant is that you are “putting all of your eggs in one basket.” If that state’s Supreme Court or legislature later makes law that hurts your contract, you will have lost all protection against your entire workforce nationwide. Consider states like Massachusetts that have, in recent years, considered statutes outlawing non-compete agreements.

An employer should consider spreading the risk over many states’ laws, thereby eliminating the “all or nothing” effect of a choice of law provision. A similar danger exists for choice of forum clauses: if you pull all of your cases from all 50 states into the county where your corporate headquarters is located, you could find yourself at the mercy of perhaps just a handful of judges who hear emergency injunctive applications. One or two judges who do not like covenants, or who get sick of seeing what they think are “too many” of your company’s cases from out of state, can hurt your enforcement program nationwide. Of course, you could get lucky and have one very favorable hometown judge who handles all of the cases, but the opposite is just as possible. For most companies, such a “feast or famine” scenario is undesirable — it is usually better to spread the risk by litigating the cases where they arise.

How do I keep track of all of these agreements?

Common concerns about accommodating the reality of variations among the states are, “How do we keep track of all of these agreements?” or “Our branch offices will never get it right if there are too many contract versions kicking around the company.” These are legitimate concerns, but they are far from insurmountable problems. After conducting the three-step analysis previously mentioned, you may conclude that your interests are best protected if you create, for example, four different versions of your restrictive covenant: one for your home state and other “typical states," and three for so-called “problem states.” Or suppose you are a very large company with many categories of employees in numerous states. Administering your non-compete program in a substantial multistate environment may seem daunting. But, while administering a multistate program may seem difficult, it is eminently workable with the right system in place.

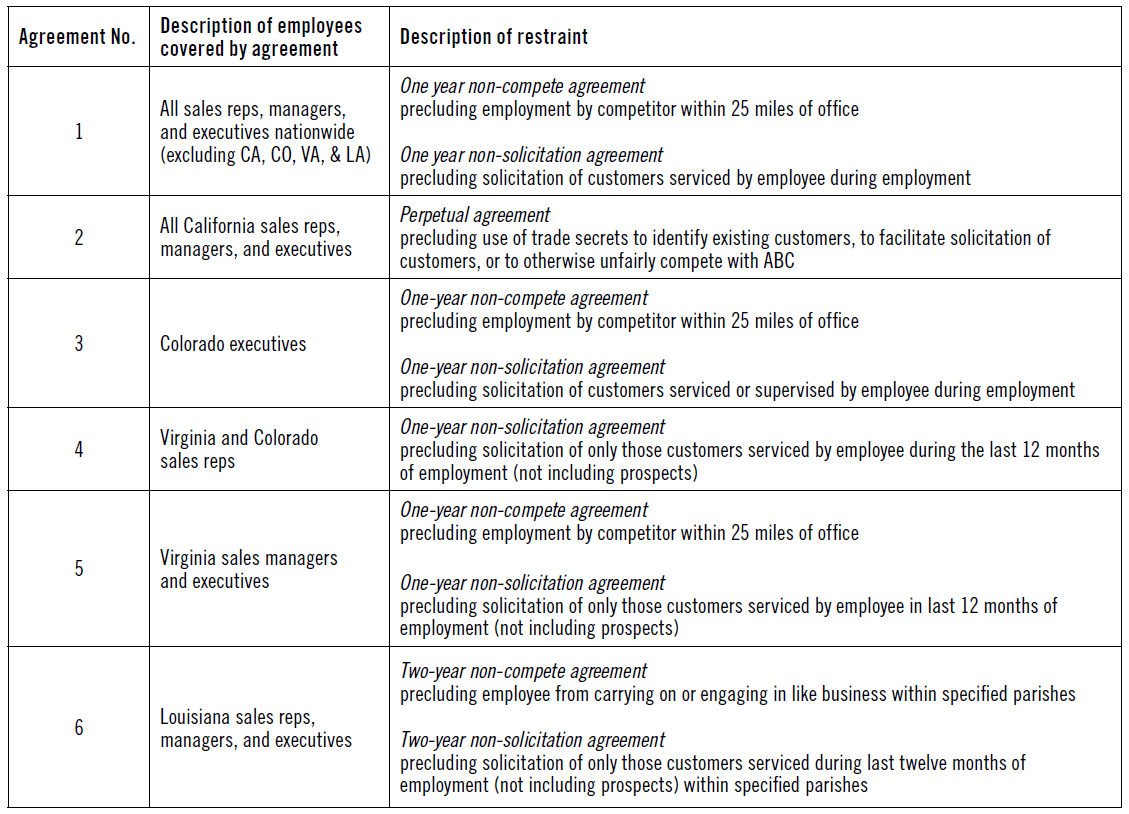

Below is a table created for a fictitious company, ABC Corporation (ABC). ABC, which is headquartered in Denver, Colorado, has employees in 10 states across the country, including Ohio, Pennsylvania, California, Louisiana, Virginia, Minnesota, Missouri, Florida, and Michigan. ABC has a trade secret customer list, thrives on cultivating its customer relationships, and requires protection against departing sales representatives, managers, and executive employees. After conducting the analysis in steps one to three above, ABC concludes that it needs six different versions of its post-employment restrictive covenant:

- Version #1 can be executed by most ABC employees nationwide (except by those employees covered by version nos. 2-6). Although a court might find it overly broad, the odds are that it will be enforced — or at least judicially modified — to an acceptable scope.

- Version #2 contains an agreement for California employees designed to protect against use of its trade secrets to identify ABC’s existing customers, to facilitate solicitation of ABC’s customers, or to otherwise unfairly compete with ABC.

- Version #3 applies to executive level employees in Colorado and is tailored to satisfy the statutory prerequisites that apply in Colorado.

- Version #4 applies to sales representatives in Virginia and Colorado. Because overreach can be fatal in Virginia, ABC has chosen to limit its protection to a narrowly drafted non-solicitation agreement. In light of Colorado’s statutory restrictions, ABC has chosen the same restraint for its Colorado based sales representatives who have access to trade secret customer information.

- Version #5 applies to Virginia sales managers and executives. Although overreach can be fatal, ABC has concluded that it requires managerial and executive level employees to execute a noncompete agreement in addition to a non-solicitation agreement, and feels it can and must try to defend this restraint against challenges in Virginia by higher level employees.

- Version #6 applies to Louisiana sales representatives, managers, and executives. This agreement tracks the unique statutory prerequisites that apply in Louisiana, while providing ABC with the protection it believes it needs.

The table set forth above summarizes the six versions of ABC’s restrictive covenant, and provides an easy reference from which ABC’s Human Resources professionals or even regional site managers can discern which contract needs to be executed by which employees.

Some miscellaneous thoughts

Following the steps set forth above is a great start, but coordinating a multi-jurisdiction program of enforceable restrictive covenants requires more than good drafting. For instance, in states like Colorado, the enforceability of a non-compete agreement may depend upon whether the covenant is necessary to protect a trade secret. Having a trade secret requires employers to take reasonable steps to preserve the secrecy of their confidential information. Similarly, companies should consider the extent to which they are prepared to enforce their agreements. Non-compete litigation is expensive, and the costs are often front-loaded. Companies that plan to enforce their agreements sporadically may face arguments that the restraints are not necessary to protect their legitimate interests. Another issue to consider is whether the agreements will be supported by adequate consideration. In many states, a job offer or continued employment will suffice as consideration. Other states may require more. The nuances of these variations are abundant, but worthy of analysis. Turning a blind eye may render even the well drafted covenant unenforceable.

Conclusion

In short, employers operating in multiple states should be aware of the differing approaches to the enforceability of restrictive covenants, and draft agreements with those considerations in mind. Employers should beware that a “one-size-fits-all” approach to restrictive covenants may come back to haunt them. Drafting agreements up front that take into account the law of the state where the employee is located will heighten the prospects for successful enforcement. Keeping track of who signs what agreement may seem daunting, but a little organization goes a long way. With some planning, you can administer a workable non-compete program in a multistate environment.