As an in-house lawyer based in Silicon Valley, one of the most popular agreements is the nondisclosure agreement (NDA) or confidentiality agreement. The latest trend for corporate offices is to mandate that all visitors, including the pizza delivery person, sign an NDA on a tablet computer before taking a step beyond the lobby.

Despite its ubiquity, the NDA might also be the most detested or at least misunderstood business agreement. Many non-lawyers, when asked to sign an NDA, declare that “it isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on.” Despite the irony of this statement when they are using a tablet computer and e-signature, rather than printing on paper, this mindset about NDAs raises important questions for in-house lawyers:

- Are we successfully heeding best practices if we limit our use of NDAs?

- Or are we wasting our valuable time working on any NDAs?

To answer these questions for ourselves and our internal clients, we need to consider the purpose of NDAs and the consequences if they are breached.

Shhh, can you keep a (trade) secret?

One of the most important reasons that organizations put an NDA in place is to protect their trade secrets. Treatment as a trade secret is a preferred form of protecting certain types of intellectual property. While novel mechanical inventions and new molecules can be protected through the patenting processes, there are many other types of important, hard-earned intellectual property that are not appropriate to be the subject of a patent filing. These non-patentable forms of intellectual property range from customer lists to business methods to future product roadmap.

Even if a piece of intellectual property could be patented, its owner may elect to utilize trade secret protection for other reasons. In order to file a patent, the intellectual property needs to be disclosed to the public eventually when the patent is published. By contrast, there is no requirement to publish trade secrets. Trade secrets also afford a long period of protection: Patents expire after 20 years and enter the public domain, whereas trade secret protection can be maintained indefinitely.

Without NDAs, your trade secrets are at risk

A key tenet of trade secret law is that a company cannot seek trade secret protection for intellectual property that you do not safeguard itself. A dietary supplements manufacturer discovered this rule the hard way when it lost its bid to accord trade secret protection to a list of its distributors when it had previously publicly disclosed the identity of the distributors elsewhere.

The lesson for your own organization is clear: Do not disclose information that you consider to be a trade secret unless there is an NDA or some other disclosure restriction in place with the recipient. The next time a colleague declares NDAs worthless or irrelevant, ask him if he thinks your organization should protect its trade secrets.

If the answer is “Yes,” then explain to him that NDAs are essential for doing so. And if the colleague answers “No, we don’t need to protect our trade secrets,” then it’s time to dust off his employment documents and explain that he likely committed to maintain confidentiality of company information.

Good NDAs make good neighbors

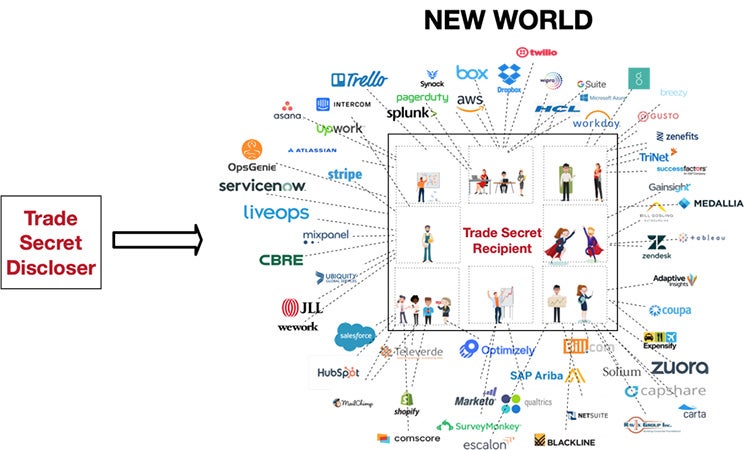

In addition to one’s own trade secrets, many companies are charged with the safekeeping of the trade secrets of partners, customers, and vendors. The original owner of the trade secret is typically only willing to share the trade secret if the receiving party agrees to maintain its confidentiality.

Companies are more dependent on outside services than ever before for their core business functions, such as running computer services and processing invoices, are often handled by a third party. This means that the recipient of a trade secret has a high likelihood of exposing the trade secret to a third party.

This method of protecting the original trade secret discloser has proliferated more NDAs, from the trade secret recipient to its many service providers. And, of course, each service provider likely has its own service providers.

The result is a tangled, often recursive web of NDAs. What this means for you as an in-house counsel is that your company is likely breaching many contracts if it does not have NDAs in place.

Surprise: The stove really is hot

While the reason to have an NDA in place is to protect your organization’s trade secrets and avoid breaching its contracts with customers, is there any real consequences if the counterparty does not adhere to the NDA? Absolutely.

Consider the case of a small technology company and a major nationwide retailer. Pursuant to an NDA, the tech company revealed to the retailer features and processes of a new type of electronics buyback program that were a proprietary trade secret. Subsequently, the retailer launched its own remarkably similar product program without the tech company. A jury found that the retailer’s violation of its NDA with the tech company was willful and malicious and awarded the tech company US$5 million in punitive damages, on top of US$22 million in direct damages.

Not surprisingly, the majority of the award in the case was direct damages stemming from economic loss. What this means for you is that if you identify that an NDA has been violated, you should immediately start assessing the cost to your organization of your confidential information and trade secrets being disclosed.

The in-house lawyer as an educator

The combined proliferation and underappreciation of NDAs creates an opportunity for you as an in-house counsel to explain to your colleagues the rationale for documents you are asking them and your business partners to sign.

Focus your colleagues on the protection of trade secrets and your contractual obligations to others as the driver for putting NDAs in place whenever confidential information will be shared. And if the desire to reduce business risk doesn’t motivate them, remind them of the potential economic impact of an NDA violation.