CHEAT SHEET

- Instability. Even while career prospects for Brazilian in-house lawyers are sunny, their relatively low professional happiness may be attributable to political or economic uncertainty.

- Trying times. The ongoing political shakeup and corruption scandals sweeping the country should remind executives that in-house counsel, the arbiters of compliance, ought to be listened to.

- If I could save time in a bottle. Satisfactory compensation rates are undercut if in-house counsel lack time outside of work.

- Compliance challenges. Brazilian in-house counsel are especially preoccupied with complying with local laws as a result of corruption.

Five thousand in-house counsel from 73 countries told the Association of Corporate Counsel what they thought about job satisfaction and career mobility in the recently published 2015 Global Census Report. As a member of the Brazilian corporate lawyers community for five years and an ACC member, I encouraged my compatriots to participate in this census.

To my general surprise, my Brazilian colleagues contributed nearly 100 responses, making Portuguese the second most chosen language to fill the questionnaire.

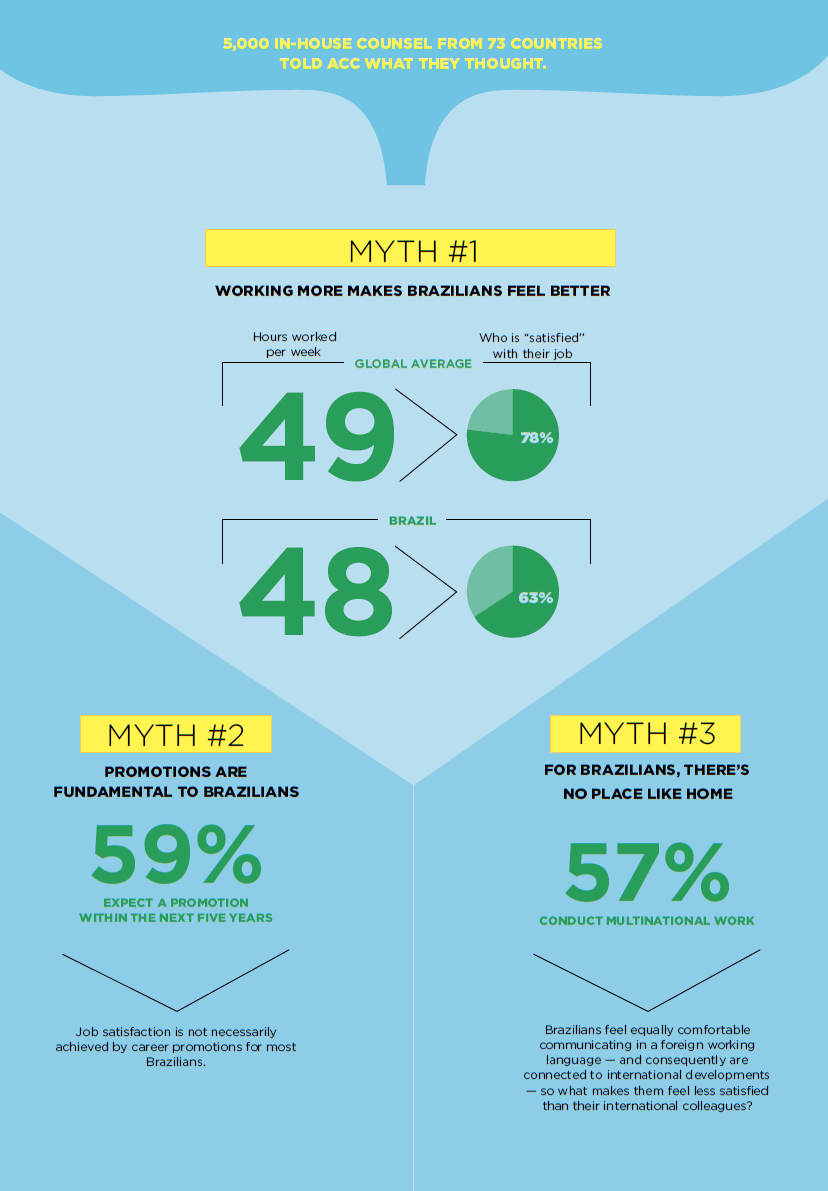

Despite the positive participation from my Brazilian colleagues, not all the facts were encouraging. One fact in particular caught my attention: Far fewer corporate counsel in Brazil report high job satisfaction (63 percent) than with their peers around the world (78 percent).

This article will investigate the possible reasons behind the data while also busting some statistical myths.

Statistics myth busted #1: Working more makes Brazilians feel better

In my opinion, this is the most significant myth busted by the census.

In a country with so much poverty, common sense says that people who practically live at work will achieve true happiness.

Wrong. Money does not always bring you a good life.

The fact that many lawyers are transitioning from private practice to in-house activity — and thus lowering their income — refutes the premise that more money equals more happiness.

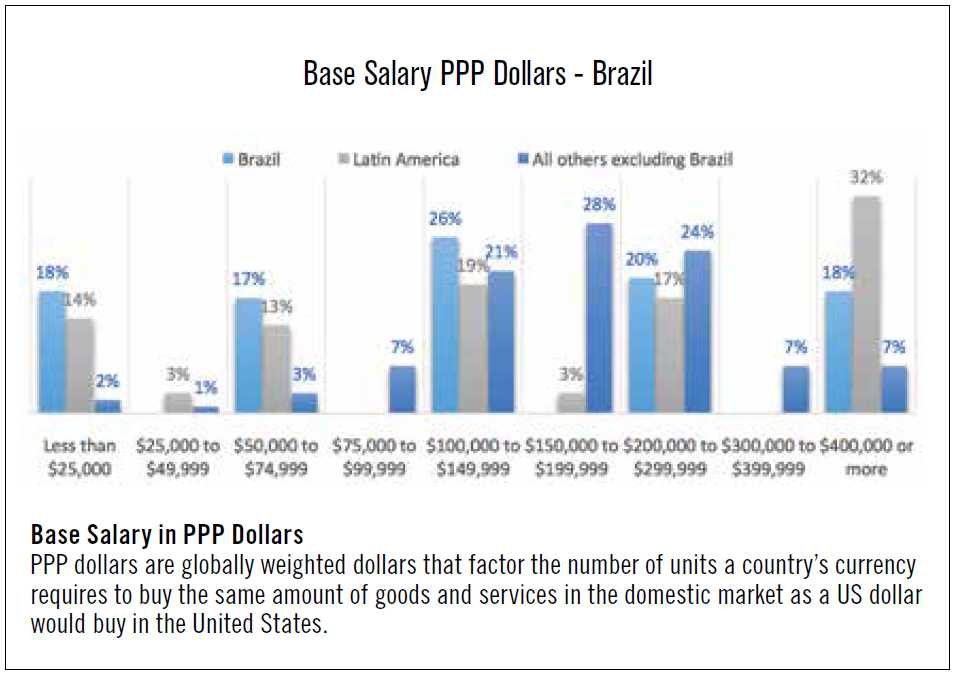

Most of the surveyed counsel confirmed an annual income between PPP $100,000 and PPP $299,000* — a huge difference from the average profits for each private practice partner of around US$1 million (or more) per year at many large law firms.

* Purchasing power parity conversion factor is the number of units of a country’s currency required to buy the same amounts of goods and services in the domestic market as a US dollar would buy in the United States. The PPP exchange rate for 2013 is used for the standardization of currencies (the Latest data available from the World Bank). For more information on PPP and weighting the data, please see the methodology section of the ACC Global Census available at no cost at www.acc.com/surveys.

However, the census also reveals that even highly compensated in-house counsel experience dissatisfaction with their current positions.

Why are fancy offices, luxury cars, glamorous houses, and very expensive clothing no longer seducing all kinds of lawyers?

Maybe because they simply have no time (and perhaps enough mental and physical sanity) to enjoy everything this way of life provides them.

Other values — like having a family, or some free time for hobbies, or even having just enough money for basic needs — could be changing the priorities of some.

It is no longer unknown whether an in-house environment provides a better work-life balance than in private practice. For example, we know that work-life balance is a driving force behind the flow of outside counsel to in-house positions. According to the 2014 ACC Global Work-Life Balance Study of over 2,000 in-house counsel, 55 percent of current in-house counsel say work-life balance was a large factor in their decision to go in-house and another 27 percent said it was somewhat of a factor. Furthermore, in ACC’s 2015 Global Census Report, among the 3,400 who shared what attracted them to an in-house position, work-life balance ranked among the top issues cited by a vast majority. Three quarters of those who participated in the 2015 Census say they are more satisfied in-house than they were working in an outside firm or legal position.

In Australia, in-house lawyers were likely to be paid less with fewer promotion prospects yet they were more likely to enjoy work-life balance, possibly because they worked 47 hours a week on average, which is under the global rate of 49 hours.

For a North American perspective, it is fair to assume that even working 50 hours for a company is more favorable than the 60 or more hours per week most US law firm lawyers work. Eighty-three percent of US corporate lawyers are satisfied with their jobs.

And the scenario seems to be more comfortable to Brazilian lawyers: The census reveals they are (under purchasing power parity methodology) among the best-paid corporate lawyers in the world though they are not required to put in more hours (48 hours per week) compared with the average in-house counsel worldwide (49 hours per week).

Notwithstanding that fact, Brazilian in-house counsel report even minimal positive job satisfaction at low rates (63 percent). Just 30 percent say they are very satisfied with their current position, and 29 percent are somewhat satisfied.

This fact is particularly odd when the analysis includes a broader regional range.

In Latin America (including Brazil), the census demonstrates that base salaries were more likely to be in the highest and lowest salary categories rather than in the midrange, meaning that there is a widening gap between the highly paid and the lesser paid in the in-house counsel community. According to the census, in-house counsel in Brazil and in Latin America overall were more likely to report the highest or the lowest base salaries. Roughly 18 percent of the in-house community earns a base compensation of PPP $400,000 or more in Brazil, while around 32 percent in Latin America earn over PPP $400,000. These figures are far higher than the seven percent who report earning PPP $400,000 per year outside of Brazil.

Comparing such disparities to the United States — where the vast majority of in-house lawyers are satisfied with their jobs — makes the reality very clear. Less than three percent of US corporate lawyers earn US$400,000 (or more) while about 97 percent earn less than US$400,000 annually. Yet 48 percent of all US in-house counsel respondents say they are “very satisfied” with their job compared to 32 percent who are very satisfied in Brazil.

This is sufficient to say that a better salary and fewer hours in the office do not equate to higher job satisfaction.

Statistics myth busted #2: Promotions are fundamental to Brazilians

Another interesting myth busted by the census is that career movement is a sign of professional happiness. Among in-house counsel working for companies headquartered in Brazil, 59 percent say they expect a promotion within the next five years.

Around 55 percent of Brazilian in-house lawyers have an expectation of career advancement in four years or less, representing the fourth-most optimistic group at the global scenario.

Still, this especially conflicts with the fact that many Brazilians in general are unsatisfied with their jobs, which leads to the assumption that the main problem does not concern the in-house career itself.

External factors — like political or economical instability in general — suggest that they might play a big role as “hidden villains.”

This said, ultimately, job satisfaction is not necessarily achieved by career promotions for most Brazilians.

Statistics myth busted #3: For Brazilians, there’s no place like home

The myth that internal lawyers prefer to work locally, and thus solve local problems with no concern from the “outside world,” is also busted by the census.

The cross-border activity found in the census shows that larger organizations tend to have more global concerns.

Companies headquartered in Europe have high multinational activity — 86 percent of companies reported multinational activity. In-house counsel from Belgium, Germany, and Switzerland lead the group with 95-100 percent of cross-border activity.

On the other hand, United States, Canada, Australia, and Brazil reported low levels of multinational work (between 57-59 percent).

What common attributes do three of those four countries share? Apart from Brazil, they all share a working language.

Considering that English is the current “lingua franca,” (i.e., the primary language for international relations and foreign exchange) language barriers practically do not exist among native English-speaking lawyers when dealing with cross-border issues.

This may be considered a positive asset regarding job satisfaction levels in English-speaking countries like Canada (86 percent), the United States (83 percent), the United Kingdom (78 percent), Australia (78 percent), and South Africa (75 percent).

Once again, Brazilian statistics don’t follow the results of other countries. According to ACC’s research, slightly over half of Brazilian respondents (54 percent) preferred to answer the questionnaire in Portuguese (with just two individuals answering in this language outside Brazil).

Although this shows that nearly half of Brazilian in-house lawyers are doing well by learning and practicing the “lingua franca” alongside their own native language in the business world, Brazilians still reported low levels of multinational work (57 percent).

If half of Brazilians lawyers feel comfortable to communicate in a foreign language, why do cross-border work and job satisfaction rates remain low?

Perhaps a geographical answer explains the first question.

Indeed countries that border more than one country and where there are at least two official languages (like Switzerland, Belgium, and Hong Kong, with four, three, and two official languages respectively) may be more likely to develop a sense of international community.

The only “exception” remains with the German in-house community who has only one official language — although in practice it is almost impossible to find a German in-house lawyer who speaks less than two foreign languages (one of them normally with absolute fluency).

There is no specific scientific evidence solely based on this thought, but it would not be unreasonable to make the assumption that the more languages a corporate lawyer knows, the more global perspectives she or he gains, which in turn allows them to solve common problems around the world.

And certainly the more solutions to the same cross-border problem a lawyer has, the less frustrations would remain at the table.

Consequently, a corporate counsel who always stays in his or her geographical and linguistic comfort zones will have less chances to improve his or her job satisfaction.

Then, if Brazilians feel equally comfortable communicating in a foreign working language — and consequently feel more connected to international developments — what makes them feel different than their colleagues from the rest of the world regarding their job satisfaction level?

Behind the numbers: The good, the bad, and the ugly

As stated before, Brazilian corporate lawyers have very positive levels of salary, working hours per week, career advancement expectations, and meaningful “linguistic” cross-border activity.

Still, a lower percentage of corporate lawyers working in Brazil are somewhat to very satisfied with their job (62 percent) compared with the global average (excluding Brazil) of 78 percent.

Is there a cause for this?

I believe the answer again could be found in the census.

When looking at the issues that keep in-house counsel up at night, the survey shows that corruption posed greater internal challenges for those in Latin America. Twenty-eight percent of in-house counsel in Latin America report they encountered greater challenges in complying with the laws in their jurisdiction as a result of corruption. This is significantly higher than the global average (four percent) and second only to corporate counsel in the Asia Pacific region (41 percent) who rated this as a top challenge in their jurisdiction.

Generally speaking, corruption in Latin American countries has existed forever, so this issue is absolutely not new.

But what are the reasons behind this old problem playing a more crucial role now?

It is no secret that Brazil is currently facing one of the most difficult political and economical crises since the 1980s and governmental instability is affecting the Brazilian business world.

The most emblematic example is the Brazilian federal police operation named “car wash,” which has resulted in the arrest of not only politicians and other governmental officers but also very famous CEOs from big Brazilian companies in the last two years.

Police investigations show that risk assessment and management, as well as ethics and compliance, had been given little attention by company executives.

While the global trend shows that more than half of all corporate counsel are working to elevate their role as strategic business partner, many Brazilian companies are still resistant to that view. They do not see internal lawyers as trusted advisers, business partners, and strategy participants.

In other words: In-house counsel should be more than just a constant presence in the corporate meetings where transparency issues come up.

They should also have an active voice and their words must be taken seriously before the adoption of any decision with potential risk for the future of a company’s business.

It is no wonder that one of the accusations brought by a class action states that there was a lack of sufficient risk assessment and management by Brazilian oil giant Petrobras when it reviewed contracts worth millions.

I have no doubt that there is a direct relation between corporate accountability and the level of in-house presence at the executive table.

Unfortunately, for now, the career prestige of the Brazilian in-house counsel is seriously at stake. Fortunately, it is not because of its technical and professional skills. Sadly, it is due to old habits still cultivated among Brazilian businessmen in general.

This certainly frustrates all in the Brazilian in-house community — regardless of salary, workload, career perspective, or preference to think outside the box.

The author would like to give some very special thanks to Robin Myers for providing additional data from the census and to all Brazilian members of the in-house community who helped ACC by providing very helpful insights to the 2015 Global Census.