CHEAT SHEET

- Setting the stage. Once counsel have decided on a strategy, implementation with stakeholders is critical. In-house counsel should take the lead in bringing the key players at the company to the table.

- Plot twist. It is critical that in-house and outside counsel have a candid discussion about upcoming responsibilities as soon as an investigation starts. Allocation of roles should be broader than traditional descriptions.

- The climax. If it becomes apparent that continuing discussions between the government and the company will not lead to a narrowing of differences, there is a possibility that the company will be headed for litigation. In-house counsel should provide senior executives with a thorough description of its cost and risk assessments.

- Epilogue. After a decision has been made regarding a settlement agreement, it is critical that in-house counsel ensure future compliance with these new obligations.

Setting: You are the in-house counsel for a large financial services company that takes great pride in its stellar reputation and commitment to compliance. You’ve worked with regulators, auditors, and outside counsel for years to develop a sound compliance management system. Your outside counsel is a trusted friend who tells you what you need to hear, and who has assisted your company with especially difficult legal and policy issues.

You think all is well.

But then out of the blue, you learn that an aggressive government agency has launched an investigation into your company’s collection practices and has served a Civil Investigative Demand (CID), seeking extensive company records to be produced within a short period of time.

What do you do?

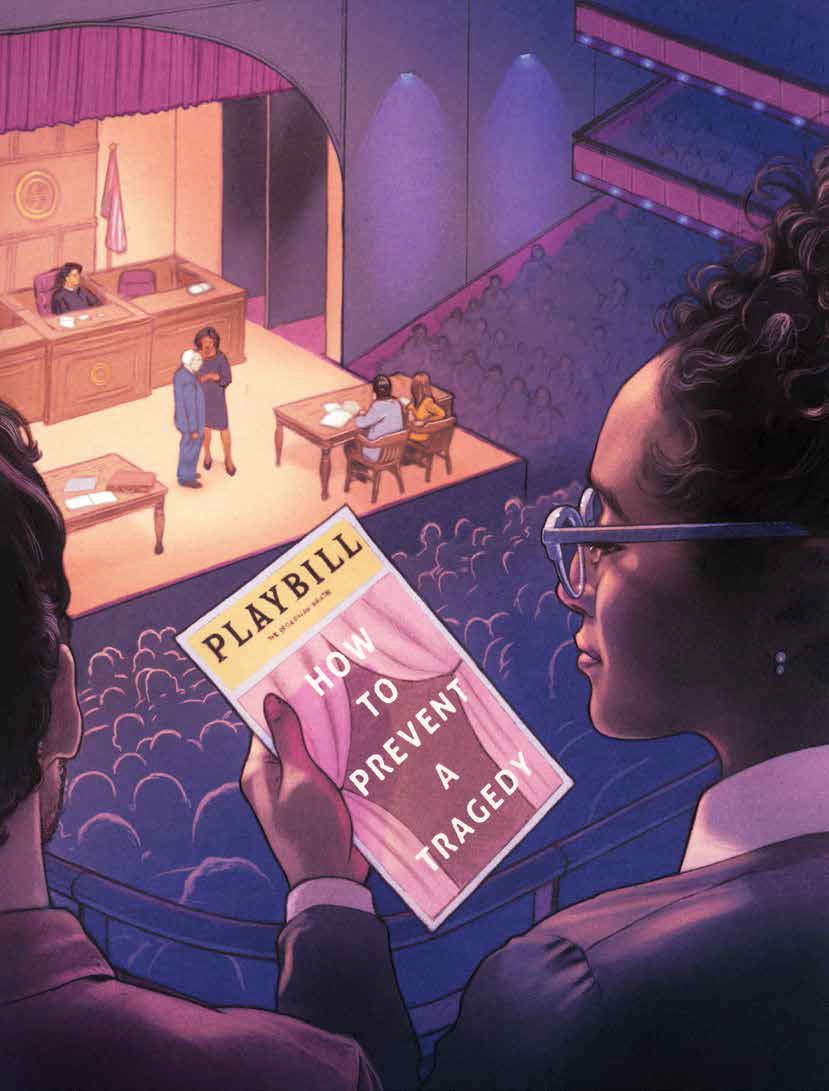

It is said that most Shakespearian plays are either comedies or tragedies. His comedies have happy endings. His tragedies not so much, as most of the protagonists end up dead. Here are thoughts about the roles that in-house and outside counsel play in a government investigation and litigation drama to prevent a tragedy.

Characters: The two main protagonists in our play are in-house counsel and outside counsel, and they work together to respond to government investigations and litigation. They are adept at working for companies, law firms, and government enforcement agencies on such matters. One of them was a long-time federal regulator (gasp!) — meaning that they both have experience on opposite sides of a CID.

Any government investigation can be viewed as a play made up of a standard set of acts and scenes. Our characters will walk you through each of them, offering what in-house and outside counsel can do, alone or together, to achieve the best possible outcome for the company.

Having set the stage and outlined the main characters, let’s begin.

Prologue: Establishing a culture of compliance

Of course, no company truly ever “wants” to be subject to a government investigation. But if you are, your company can take some comfort from its compliance work over the years, assuming it has established and maintained a “culture of compliance.”

Scene one: Deciding on roles to achieve a culture of compliance

Both in-house and outside counsel play key and complementary roles in creating a culture of compliance. During their review of business operations and proposals, in-house counsel are responsible for identifying possible legal and policy issues. In-house counsel may address many of these issues themselves, but often seek to involve outside counsel when the issues are especially nettlesome or complex (or to help convince the business-folks that internal counsel are correct). Oftentimes, outside counsel may have greater experience with a body of law or a specific industry or government agency that they can bring to bear in resolving these difficult issues. Looking ahead to examinations or investigations, it can be useful to obtain formal opinions on controversial issues, as many regulators view opinions from well-respected outside counsel as more independent than those of in-house counsel. Such an opinion also provides a strong argument that the company did not intentionally break a rule — mitigating any potential sanction.

Choosing when to use outside counsel requires in-house counsel to consider the need for expertise, timing, and cost. Analysis helps, but frankly, we recommend trusting your gut. If in-house counsel have a gut feeling that they will not be comfortable either resolving an issue on their own or making a recommendation to their boss about it, then they should strongly consider checking with outside counsel. If the issue is novel and there is a risk that a regulator or attorney general may someday disagree with in-house counsel, obtaining an opinion from outside counsel may be money well spent.

This gut-check approach might be particularly useful for an in-house counsel’s job security. What the company may once have considered prudent frugality may, in retrospect, be penny-wise and pound-foolish once a CID hits.

Scene two: Plotting and implementing compliance strategy

Once in-house and outside counsel are both involved, they need to come together to develop a strategy for resolving compliance issues. Outside counsel must understand not only the law and the market, but also the company. With knowledge of your business operations, outside counsel should be able to suggest scalable solutions. Together, in-house and outside counsel should find options that lower legal risk in a practical way.

To ensure a positive outcome, in-house counsel should underscore the business strategy and outline what needs to be done to make it a success. The best compliance solutions oftentimes get the company praise, boosting its reputation and reinforcing employee commitment.

Once a strategy has been chosen, implementation with stakeholders is critical. In-house counsel would be wise to follow the proverb: “Vision without implementation is hallucination.” Legal departments have not always done a great job in selling options to company stakeholders. In-house counsel should take the lead in bringing the key players at the company to the table.

Outside counsel, however, can also be instrumental in getting the word out through presentations to company staff. To be effective, the compliance strategy must be reflected in the company’s written policies and procedures as well as in its training programs. Jointly, in-house and outside counsel can roll out changes to reach the maximum number of stakeholders at the company. But, also remember that new policies must be understood and should be tracked to ensure they are efficient. Companies must praise employees for their compliance efforts to sustain a virtuous cycle of compliance.

Scene three: Executing the details of the plan

Long ago, John McKay was coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, a US football team, during a long, winless season. At a press conference, he was asked for his opinion about his team’s execution. He paused, and then responded, “I would be in favor of it.”

To avoid turning our play into a tragedy, it is important to execute the game plan rather than the company itself. Compliance is not improv. The company team should be executing the plan that counsel has developed as part of its overall compliance strategy. This means training, testing, auditing, tracking, and recordkeeping during day-to-day operations. Employees must follow the company’s written policies and procedures and the company must keep a record of their compliance.

In our experience, it is in the execution where compliance is most likely to break down. Government investigators often find policies and procedures that would have kept the company compliant. Yet employees did not follow the procedures (or the company lacked records to show that they did) and the company was, therefore, suspected of violating the law. Whether guilty or innocent, the result was an expensive, intrusive, and distracting examination or investigation, followed by a consent order or litigation.

In-house and outside counsel should work together on approaches, such as compliance monitoring systems, refresher courses on company policies and practices, and incentives and disincentives, to decrease the risk that a plan that looks great on paper becomes a dead letter in practice.

Early identification of issues and the incorporation of solutions into written policies and procedures are key steps in establishing a culture of compliance.

This is hard and expensive. But, it will all be worth it when a government investigation starts.

Act I: Responding to government investigators

Scene one: Allocating roles and responsibilities

In the best-case scenario, in-house and outside counsel will have discussed their respective roles and the roles of other stakeholders, such as the board and executive team, before a government investigation even starts. Typically, these roles will be defined in a written policy that identifies key players who:

- Must be called immediately when the company receives notice of an investigation;

- Will be responsible for document preservation;

- Will represent the company in initial meetings with the investigators; and,

- Will oversee the company internal investigation.

If such a policy is not in place prior to the commencement of a government investigation, it is critical that in-house and outside counsel have a candid and comprehensive discussion about these roles as soon as an investigation starts. Well-placed epithets directed at the government agency at this point are typical and cathartic, and they encourage counsel to become closer allies in opposing a common adversary.

Sometimes in-house counsel and outside counsel will have worked together on a previous government investigation, and sometimes they will have not. While in-house counsel will have a much better idea of what responsive documents and information the company may have, outside counsel will have experience dealing with investigators and enforcers from the government agency.

Taking advantage of each counsel’s comparative expertise leads to the most effective and efficient response. Outside counsel may be better suited to lead the initial “meet and confer” discussions with the government agency. Note that investigations are different from examinations, where outside counsel may be viewed as intimidating or interfering with communications. Later, during the production stage of the investigation, the division of labor typically involves in-house counsel working with company staff to identify, preserve, and compile responsive documents and information, with outside counsel then reviewing them for privilege and producing those that are non-privileged to government investigators and enforcers.

Allocation of roles and responsibilities extends beyond those of counsel. As such, counsel must discuss hiring other outside experts or companies as soon as possible to assist in the production in the government’s preferred format and the potential need to purchase discovery-based solutions, such as e-tools. In addition, counsel should discuss and resolve the role of company executives and department leaders in responding to the investigation. Outside counsel may take the lead role in preparing company personnel for depositions and interviews, as few in-house counsel have the resources for this type of hands on work.

As mentioned above, another key role will be running the internal investigation, which a prudent company will undertake for a number of reasons:

- By finding out all of the key facts that the government is going to uncover before the government does so, the company can make important strategic decisions about how to handle the matter. In our hypothetical case, the company wants to interview its collections personnel before the government gets to them to find out what they are going to say and prepare them for the investigation.

- Starting an internal investigation shows the company is taking the problems seriously and is being proactive.

- Discovering and diagnosing the cause of the investigation as early as possible permits the company to begin remediation measures, minimizing the damage and also impressing the government.

- The internal investigation will help in organizing and reviewing the documents that will need to be produced for the government.

In-house and outside counsel should have periodic discussions about their roles during investigations to respond to changes. The inevitable adjustments that will occur during the government investigation often warrant reconsideration of the roles of many stakeholders. It is helpful to all involved to reduce these roles to writing and update them as changes occur.

Scene two: Funneling the investigation

In-house and outside counsel must also work quickly and collaboratively to respond to and “funnel” what the government is seeking in its investigation. Government investigators do not get lauded for drafting precise and narrowly-tailored documents and often get criticized for what they miss. Oftentimes, government investigators do not understand the documentation and information practices of specific companies well enough to draft precise and narrowly-tailored demands for information. So, it is best for counsel to reconcile themselves to the likelihood that the government’s initial demands will be vague and overbroad.

“Funneling” is critical to minimize broad government requests and mitigate the burden and cost of responding to them. In-house counsel, outside counsel, and company staff (e.g., IT staff) should work together to develop a realistic assessment of how long it will take and how much it will cost to obtain, compile, and provide responsive documents and information. This assessment can persuade government investigators to narrow and clarify their demands to the company. It may also induce government investigators that there is a lower cost substitute to the documents or information they are seeking.

Scene three: Managing company expectations

Perhaps the most painful part of handling a government investigation is dealing with the risk of overreactions from all actors. Managing expectations early and often during the investigation can help minimize this risk. In-house and outside counsel should meet immediately with company executives once a government investigation has commenced. Counsel must provide them with a clear, objective appraisal of events as well as any risks to the company from the investigation. If they do, company executives are far less likely to panic and make mistakes.

Preparing the company’s employees for what will transpire during a government investigation can also decrease the risk of resentment or panic. By educating employees on investigations as part of the company’s compliance training program, it will be substancially easier for counsel to execute a response plan in the event that an actual investigation has commenced. It’s important for counsel to explain the process, scope, and timing of the investigation as clearly as possible to convey that the company is prepared. Most importantly, counsel should stress that they are there to defend the company, and that employees should do as the British World War II slogan suggests: “Keep calm and carry on.”

At any time prior to litigation, a company may decide that it wants to discuss the possibility of settlement with the government. In-house counsel and outside counsel need to develop a strategy to explain the government’s concerns and the risks of litigation. They also need to lay the foundation so that the company is prepared for the hard choices that will come in settlement negotiations. Outside counsel often can provide a sense of the conduct restrictions as well as the amount and type of monetary relief (penalties, fines, restitution, etc.) the government has obtained in similar cases, which helps prepare the company for what the agency is likely to seek to settle.

It is important to remember that the large majority of investigations end in some type of settlement, generally in the form of a consent order or agreement. Sometimes, the investigators can be persuaded that no formal action is required and they will simply close the investigation. If a reasonable agreement cannot be negotiated with agency staff, most agencies have some formal or informal appeal mechanism through which the agency takes a second look before bringing charges. The Security and Exchange Commission’s “Wells Notice” procedure is probably the most well-known example. Outside counsel can often be helpful in guiding the company through this process.

A European perspective

A recent increase in regulatory investigations in the European Union has left many companies scrambling to reorganize their compliance culture in accordance with changing legislation. In 2016 alone, the European Commission — which serves as the enforcement arm of the European Union — has called for investigations into Google’s privacy policies, Amazon’s tax compliance, Facebook’s antitrust violations, and labor protections for both Uber and Airbnb.

According to the ACC Chief Legal Officers 2017 Survey, 36 percent of European respondents reported being the target of a regulator in the past two years; a substantial increase from the global average (28 percent). Consequently, 34 percent of European respondents noted experiencing a data breach under the same timeline.

The increasing regulatory presence in the European Union serves as a perplexing scenario for in-house counsel — especially those working for large multinationals with myriad compliance requirements. Companies that were once accustomed to the leeway and appeals processes provided in other regions of the world are now faced with the realization that new standards will have to be tailored to all operations, both in and out of the region. Hasty response plans and a “do first, think later” attitude will not be sufficient enough to protect your company from becoming a target.

In a report by Bloomberg, Jacques Derenne, head of the European Union and competition and regulatory practice at Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton, discourages in-house counsel from underestimating EU regulators if they wish to continue working in the region. “Too many still experience the pitfalls of cross-culture unpreparedness,” says Derenne.

To mitigate risk, in-house counsel and outside counsel should work collaboratively to monitor changes in relevant EU standards. It’s imperative to understand the parameters of each policy and outline how internal performance will change jurisdictionally. With the General Data Protection Regulation set to take effect in Europe in 2018, in-house counsel should anticipate and modify all affected operations well in advance of the impending legislation. In addition, companies should implement and maintain a thorough record-keeping process to ensure cooperation with any regulatory investigation into compliance.

SOURCES

Silicon Valley’s Miserable Euro Trip Is Just Getting Started

CORPORATE INVESTIGATIONS & EU DATA PRIVACY LAWS - WHAT EVERY IN-HOUSE COUNSEL SHOULD KNOW [PDF]

Act II: Litigating

Once the government investigation is finished, the agency will provide the company with a settlement demand (unless the agency is closing its investigation), often accompanied by complaint or charging document that the agency intends to file. Outside counsel and in-house counsel should work together to develop and present a counteroffer. Outside counsel’s experience with the government agency often assists in identifying the “usual” provisions that are successful in settlement demands. A counteroffer should demand that the company receives provisions that are at least as favorable as the usual. If counsel did their work earlier in setting expectations, senior executives at the company should not be surprised at the contours of counsel’s recommended counteroffer and should be more likely to approve it expeditiously.

It may become apparent that continuing discussions between the government and the company are not likely to lead to any further narrowing of differences. Government agencies will usually file a complaint against a company if the parties are not able to reach a settlement.

Typically, outside counsel will work with in-house counsel to develop an overall strategy for defending in the government litigation. Outside counsel will craft a budget for the litigation drawing on the costs incurred in litigating similar cases, and submit their budget to in-house counsel for review and approval. Outside counsel commonly examine the relief that the agency obtained in past litigated cases to give in-house counsel a sense of the risks if the company does not mount a successful defense.

Armed with a strategy, budget, and down-side risk assessment, in-house counsel can provide senior executives at the company with a cogent description of how counsel intend to approach the litigation. This description and analysis helps keep counsel and senior leadership on the same page during the litigation period.

Most cases that enter into litigation nevertheless are resolved via settlements. Therefore, one issue that frequently arises is how to deal with settlement overtures and opportunities while the litigation is underway. Outside counsel frequently become aware of these overtures and opportunities in the first instance, but it is often better for in-house counsel to follow up on them. It can be difficult for outside counsel to focus at the same time on aggressively litigating a matter and actively trying to settle it. It is sometimes difficult for outside counsel litigating the matter to take a step back and consider objectively if a compromise is the best resolution for the company.

In any event, it remains critical for negotiating and litigating counsel to stay in close touch. Developments in litigation should impact negotiation strategy and vice versa. If the litigators are expecting to win a major motion, for example, it may make sense to delay making a settlement offer or counteroffer until after the judge rules. If a major negotiation session is coming up, it might make sense to file a motion before the session and before government counsel needs to answer. As a result, the government will see the strength of the company’s arguments and can avoid having to answer by reaching agreement promptly.

Act III: Moving forward

Scene one: Ensuring future compliance

Unless the agency closes its investigation or the company prevails in court, the company will be subject to an order, either through a settlement agreement or through litigation. A critical and continuing obligation of outside and in-house counsel is to ensure compliance with the company’s new obligations under the order. If a company has a culture of compliance, it is much easier to incorporate the provisions of the settlement agreement into its practices and procedures and be confident that they will be implemented. In-house counsel can draw upon its intimate knowledge of company practices and procedures in developing standards that both satisfy the terms of the settlement agreement and are practical for the company. Outside counsel can draw on its experience with the government agency’s interpretation and application of provisions in similar settlement agreements to help ensure that the company’s conduct will comply with the terms of the settlement agreement. Counsel should emphasize that any new standard from the order needs to be taken especially seriously under compliance. This is because the government can obtain even stronger remedies for company violations against an order.

Scene two: Defending the company in the press

When a government agency announces a settlement, files a complaint, or prevails in litigation, it will issue a press release. Government investigations typically are non-public, so the government press release announcing the settlement or filing of a complaint will be the first time the press and the public have heard about the matter. Government agency press releases can have a massive effect on how customers, shareholders, employees, public officials, and others view the company. The company has a keen interest in making sure that harm from the agency press release is mitigated and minimized.

Typically, government agencies will refuse to allow private parties to review or negotiate press releases about their investigations or litigation, so the company should be prepared to issue its own press release. Flying blind, unfortunately, is a necessary hazard in these circumstances. Outside counsel, however, have a sense of how apt the agency is to include hyperbole or rhetoric in its press releases. So, outside counsel may be able to provide the company and its press operation with insights in drafting a rebuttal to the government agency.

Epilogue

In the end, not having a government investigation end in a tragedy is largely contingent on planning, preparing, and executing a plan of action. In-house and outside counsel must have a cohesive objective and should work together to set the stage well before the investigators appear on the scene. If a company is prepared, the final act will not close the curtain on a tragedy, but rather on a prelude to the protagonists continued viability.